Elizabeth Warren’s announcement of how she would pay for her Medicare for All plan hinted that she won’t simply re-normalize American foreign policy after Donald Trump: As Warren pursues a transformational domestic agenda, she may have to reduce America’s global role to pay for it, argues Thomas Wright. This piece originally appeared in The Atlantic.

In the midst of a presidential campaign, it is difficult to gauge how the candidates would conduct themselves on the international stage. Sometimes what they say is designed to win a news cycle or appeal to an interest group. It is cheap talk. But sometimes the candidates reveal their true colors unintentionally. Elizabeth Warren recently tipped her hand in the form of a campaign health-care-budget document.

Warren’s announcement of how she would pay for her Medicare for All plan hinted that she won’t simply re-normalize American foreign policy after Donald Trump: As Warren pursues a transformational domestic agenda, she may have to reduce America’s global role to pay for it.

The details of this episode are complicated but important. For the past 10 years, the Department of Defense’s budget has been curtailed by the Budget Control Act of 2011, or what is commonly called the “sequester.” The sequester threatened draconian cuts to the defense budget and domestic spending in order to create an incentive for Republicans and Democrats to strike a budget deal to end the debt-ceiling crisis. The sequester was designed to be so appalling that it would never be used, but the two parties were unable to strike a deal and it came into effect.

Leaders of both parties agreed that the cuts were crude and ill-advised. To circumvent their negative effects on national security, Barack Obama’s administration loaded Pentagon spending into a separate budget for overseas contingency operations, or OCO, which was originally designed for unexpected wartime spending in Iraq and Afghanistan. By the end of the Obama administration, OCO included funding for fighting pandemic diseases, the broader U.S. presence in the Middle East, and European security. Defense and budget experts from both parties, including Trump’s chief of staff, Mick Mulvaney, have criticized OCO for years, pointing out that most of it should be part of the regular defense budget. The sequester caps on spending are likely to expire in 2021, meaning nonemergency wartime funding can finally be merged into the regular budget.

Warren has been a critic of OCO for many years, and has called it a slush fund for the Pentagon. In her Medicare for All announcement, she proposed eliminating OCO, and said she would take $800 billion from the defense budget over 10 years. That number seems to be the total amount in OCO (now $77 billion a year) plus inflation. Warren justifies this approach by saying that the United States must end the forever wars in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan.

But Todd Harrison, a budget expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies who has dived deep into the details, told me that the forever wars account for only about $20 billion in OCO annually. The remaining billions include funding for things such as the Fifth Fleet in Bahrain, much of U.S. Central Command, and the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI), which is intended to bolster U.S. forces in Eastern Europe and the Baltic states. Although Warren said that some of what was funded in OCO could be moved over to the regular budget, her campaign did not say how much, or what, would be transferred.

In the week following Warren’s announcement, European policy makers worried that EDI might be on the chopping block. I asked the Warren campaign, and a spokesperson clarified that Warren sees EDI as a priority and will fund it if elected president—the first formal guarantee it has made to fund something from OCO. The spokesperson also said that if elected, Warren would cut Pentagon spending by the total amount of OCO, but that some of those savings would come from the regular budget. One way or another, her administration would reduce the defense budget by approximately 11 percent.

For many commentators, going after OCO by name sounded serious and detailed—very much on brand for the candidate with a plan. In truth, it was an accounting trick that allowed the campaign to evade questions about what it would actually cut.

How much money, for instance, does Warren intend to save by reducing the American footprint in the Middle East? In the Democratic presidential debate in October, Warren said she would withdraw U.S. troops from the region. A campaign spokesperson immediately clarified that she was talking about U.S. combat troops. But Warren’s focus on OCO will renew speculation that she meant what she literally said. If Warren just ended all operations in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan—which would be a difficult task— that would still leave a half-trillion-dollar hole in what she hopes to find from the Pentagon for Medicare for All.

Finding savings in the defense budget is possible, of course, but getting to 11 percent will require real cuts to capabilities and acceptance of greater risk in key theaters, including in the counterterrorism fight in the Middle East. The bulk of the defense budget is accounted for by personnel and long-term procurement decisions. Reducing the size of the force to rely more on new technologies may make strategic sense, but that’s not politically viable. Reducing research-and-development costs or the overseas presence may encounter less political resistance, but that’s bad strategy.

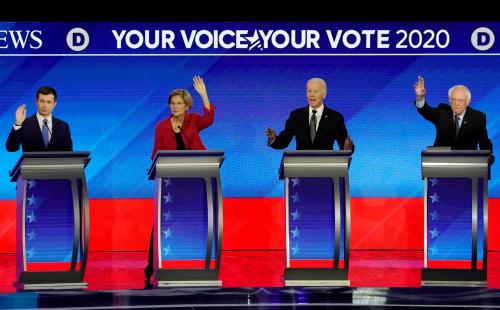

Warren may wonder why she has to get specific about foreign policy at this early stage. After all, in 2016, Bernie Sanders went until mid-spring before saying anything about it. Most other contenders are not getting pressed on details. But Warren’s situation is different. She has not avoided the topic. She has made a series of bold announcements that could transform U.S. foreign policy. In addition to the 11 percent budget cut and the pledge to withdraw combat troops from the Middle East, she has proposed new trade criteria not currently met by any of America’s existing deals. Carl Bildt, the former prime minister and foreign minister of Sweden, told me that Warren’s “protectionist impulses are not reassuring from a European perspective.”

Warren is something of an enigma on foreign policy. She and her foreign-policy advisers are cautious in what they say. She does not appear to have radical instincts. She is less critical of the foreign-policy establishment than Sanders is. She gives the impression that she wants to have a tough-minded foreign policy that stands up for liberal values globally and pushes back against authoritarianism. But she also seems to believe that the United States is overcommitted when it comes to hard power and security competition. Moreover, her domestically driven major announcements on the budget, troops, and trade will pull her foreign policy in a direction at odds with her more considered public utterances.

Warren has proposed a wealth tax to fund most of her domestic programs. Regardless of what one thinks about such a tax, it is highly likely that the conservative majority on the Supreme Court will find it unconstitutional. That will put immense pressure on a Warren administration to find funds for her domestic plans. The defense budget will be a tempting target, and the main driver will be the need to find savings that can pass muster politically. Whether they make strategic sense could be a secondary concern.

If a Democrat replaces Trump as president, they will inherit a highly volatile world that is on the cusp of abandoning the American-led post–World War II international order. Rivals and friends alike are asking the same question: Is “America first” an aberration or a sign of things to come, whether from the right or the left? They are examining every tea leaf from Trump and the Democratic hopefuls. For instance, France’s President Emmanuel Macron has cited the likelihood that the United States will pull back from the Middle East as one of the reasons he wants to develop closer ties to Vladimir Putin’s Russia. The international community is generally waiting until the election for an answer, but if they conclude that the policy is permanent, we can expect high-risk moves and further instability.

Democrats would do well to keep this in mind. Making major announcements with implications for the structure of the force and America’s overseas presence without adequate preparation will have consequences. The next administration will not have a honeymoon period internationally. The campaigns must prepare accordingly.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why Elizabeth Warren’s foreign policy worries America’s allies

November 21, 2019