Of the more than 50 elections taking place around the world in 2024, the most consequential one is in the United States, with two presumptive candidates offering radically different views of world order: Donald Trump’s America-First, economic nationalist agenda vs. Joe Biden’s transatlanticist pledge to preserve the world of alliances that America has built since World War II.

How world leaders, in particular the strongman on Europe’s periphery, view the U.S. elections reveals the nature of their regimes and the type of international order they seek.

The golden rule of international politics is for nations not to speak openly about each other’s elections, but it is no secret that in Europe, where democracies have thrived for decades, Europeans prefer Biden’s reelection. This decision is strategic and based on values. Europeans have relied on Washington’s leadership in organizing the robust response against Russia’s war in Ukraine and fear that a second Trump administration would impair Ukraine’s ability to defend itself against Russia and dramatically weaken NATO—the backbone of European security.

For the countries that comprise the European Union, the Biden administration’s attachment to multilateralism and liberal democracy is a familiar comfort zone. Yet there is palpable concern in Europe that a second Trump presidency would see the United States discard these principles, and even overlook international violations, thereby emboldening autocrats around the world—and worse, contributing to the rise of illiberal parties inside Europe.

However, not everyone is rooting for Biden.

Traditionally, Transatlanticism inferred a partnership of countries with democratic traditions—with a strong German-French axis at its continental core. Now there is an alternative trans-Atlantic axis that is no longer rooted in liberalism.

Inside Europe, there are leaders on the far-right, most notably France’s Marine Le Pen and Britain’s Brexit-champion Nigel Farage, who have struck a good relationship with the Trump world and would arguably welcome a Republican White House. Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni is a closet Trump supporter (though she has delighted Europeans with her eagerness to stand by Ukraine). The European far-right overlaps with Trump’s MAGA base in several ways, but mostly in its fearmongering on “globalist elites” and discourse on equality, diversity, and immigration. Europe’s far-right insurrectionaries think of themselves as part of the same anti-liberal revolution as Trump.

Viktor Orbán

Then there are the strongmen on Europe’s edges who are pining for a Trump win. Top among these is Viktor Orbán, Hungary’s populist prime minister and far-right conspirator. Hungary is a member of the EU and NATO but has been singing from a different hymn sheet under Orbán. Trump and Orbán’s long-standing bromance reached a new level in March when, defying diplomatic etiquette on nonintervention in other countries’ domestic affairs, Orbán visited Mar-a-Lago, skipping the White House, in support of the candidate whom he calls a “man of peace.”

For Orbán, Trump’s appeal is both ideological and strategic—and not unrequited. Hungary’s long-time leader has an iconic stature on the MAGA right and has provided something of a template on how to capture a state and its institutions for an illiberal transformation. Orbán calls it “Christian democratic politics, conservative civic politics and patriotic politics“—read anti-LGBTQ+, anti-immigration, anti-liberal. American conservatives and their institutions, including Tucker Carlson and the Heritage Foundation, have hailed the Hungarian leader as an oracle, providing speaking opportunities to inspire U.S. conservatives.

In reality, Orbán’s Hungary has seen a dramatic decline in the rule of law and free speech, coupled with rising corruption, and this illiberal trend has been at the heart of its fraying relations with the European Union and the United States. Orbán was excluded from the Biden administration’s landmark Summit for Democracy in 2023 and has frequently been chastised by the EU for his autocratic turn.

But for Orbán, Trump’s allure is not solely based on culture wars. Orbán’s support for the Trump agenda is also a strategic move in sync with his view—and ambivalence—about an imperialistic Russia in Europe’s neighborhood. Orbán’s Hungary has developed economic and strategic ties with Russia and China—and likes to use its relations with the United States as leverage against other powers. Orbán also happens to be Russian President Vladimir Putin’s closest ally in the European Union and has consistently criticized and disrupted the EU’s push to arm Ukraine against the Russian invasion, even dragging his feet on issues like Sweden’s recent bid for NATO membership.

Orbán’s preference for Trump is based on the idea that a Trump administration would be more willing to find a modus vivendi with Putin’s Russia. A widely held assumption in the policy community is that under Trump, Ukraine funding would be in peril and Ukrainians would be pushed to enter negotiations with Russia—albeit short on U.S. military aid and with a weaker hand. Countries on NATO’s eastern flank feel threatened by an emboldened Russia, which they fear would not stop in Ukraine. Orbán, on the other hand, is focused on coexisting with Russia.

After he visited Mar-a-Lago, Orbán rejoiced that Trump reportedly discussed some “pretty detailed plans” to end the war in Ukraine and promised, if reelected, to cut off funding for Ukraine. “He will not give a penny in the Ukraine-Russia war,” Orbán announced after his visit. “That is why the war will end … it is obvious that Ukraine cannot stand on its own feet.”

Vladimir Putin

Putin, too, has the same reason to want Trump in the White House.

Europeans worry that a second Trump term would start with Washington arm-twisting Ukraine to start talks with Russia, without a proper assurance of Western support and long-term security guarantees for Kyiv. The U.S. Congress’ Ukraine funding debate and Trump-allied Speaker of the House Mike Johnson’s hand-wringing over the funding bill already reveal the direction of travel.

While the idea that the war will ultimately end in negotiations is not in itself surprising among allies—a White House spokesperson has said that “The only way this war ends ultimately is through negotiation”—how and when these negotiations take place matter tremendously. In private conversations, U.S. and European officials define the endgame in Ukraine as the emergence of a strong and sovereign nation that can stand independently, even if Russians continue their de facto occupation of Crimea and parts of Ukraine. However, they acknowledge that to get there, Ukraine must be backed militarily so it can “have the strongest hand possible when that [the talks] comes.” Pushing Ukraine into talks without supplying weapons for Kyiv to preserve its battlefield position would amount to peace on Russia’s terms—paving the path to Ukraine’s permanent partition, with no security guarantees against future Russian attacks.

Putin no doubt prefers that option and may find the chances of getting there easier under Trump.

Other strategic imperatives explain why Moscow’s strongman prefers a second Trump administration, including the unavoidable discord it would create between the United States and its European allies, the prospect of NATO’s paralysis, possible U.S. inaction if Russia advances further into Ukraine, and the opportunity to further expand Russia’s footprint in parts of the Middle East and Africa after potential U.S. retrenchment from the region.

A MAGA presidency would also deliver a blow to the type of inclusive liberal democracy that Putin despises. Putin has frequently ridiculed the West’s progressive politics and transgender and LGBTQ+ rights, which he calls “Western anti-family ideology.” The Russian leader’s anti-woke credentials are no less than those of the MAGA commentators.

Interestingly, Putin has denied that he prefers a second Trump term, even though the advantages for the Kremlin are clear. When asked which candidate is better for Russia, Putin, breaking a well-established Russian tradition of not directly expressing a preference in the U.S. elections, said, “Biden, he’s more experienced, more predictable, he’s a politician of the old formation.”

Most Russia watchers believe that Putin, an ex-KGB officer who is a master of obfuscation, is trolling the American electorate ahead of the November elections and providing the Trump campaign with a useful talking point. Brookings scholar and Russia expert Angela Stent told me, “Putin feels that he increasingly has the upper hand in dealing with a divided, polarized America. Kremlin politics are such a black box that Western publics hang on every word he says, believing that he signals his true intentions. In the matter of American elections, he does not. Having hinted many times that he prefers Trump, Putin’s unexpected endorsement of Biden intentionally caused great confusion. Of course, he is toying with the U.S. public, but the Trump campaign has a new slogan: a vote for Joe Biden is a vote for Vladimir Putin.”

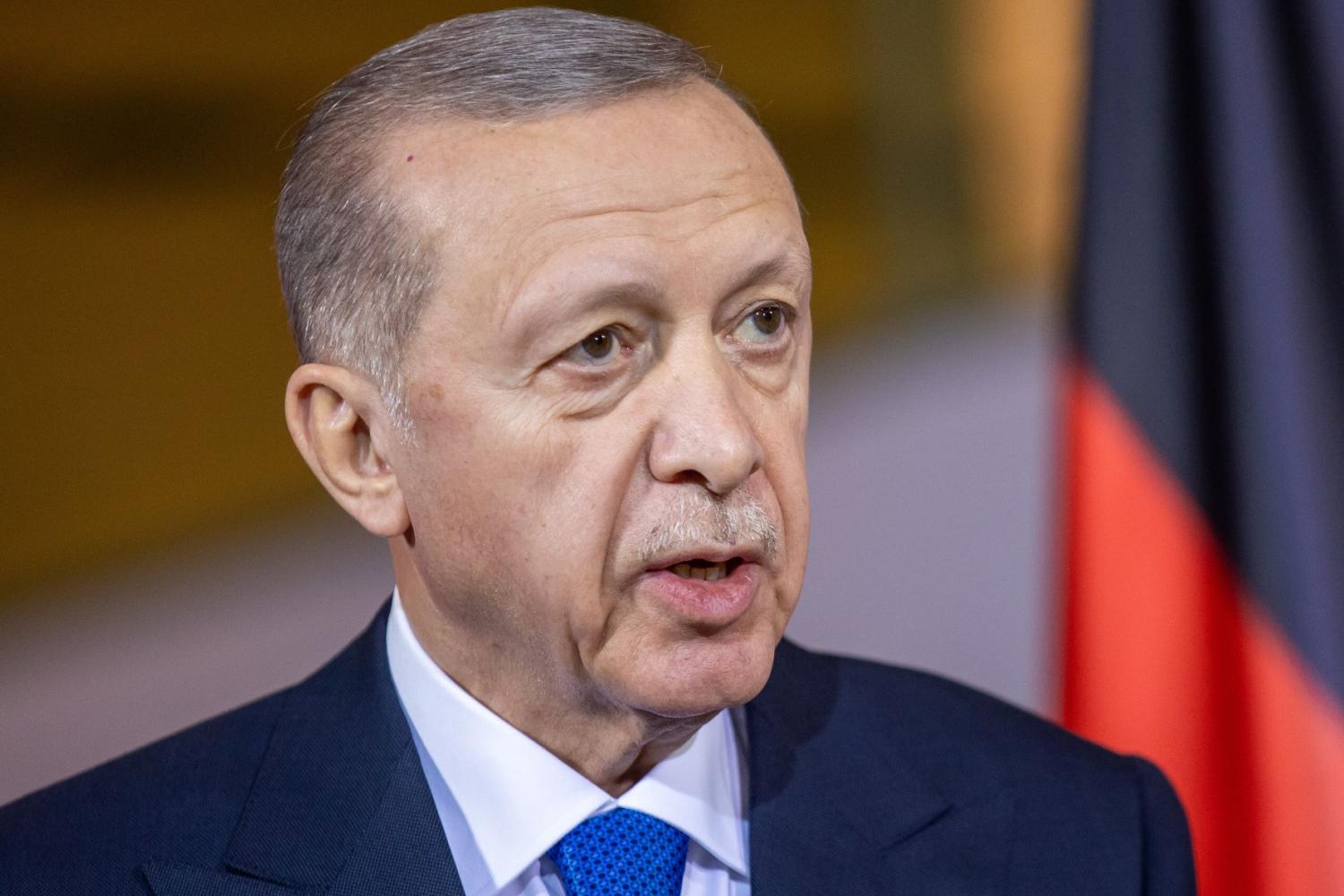

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

Further on Europe’s eastern edge, others eye a second Trump term with anticipation.

Turkey’s Erdoğan had gotten along perfectly well with Trump during the latter’s first term and would likely welcome another opportunity to leverage the international visibility and presidential access that Trump’s White House generously provided him—and the Biden administration has denied. Erdoğan imagines himself as a leader who can play a geopolitical balancing act among great powers and speak on behalf of downtrodden Muslims around the world. But over the past few years, the Biden administration and European leaders have kept Erdoğan at arm’s length because of Turkey’s democratic backsliding and proximity to the Kremlin, hence rendering him unable to showcase his international brinkmanship. Erdoğan has also been marginalized and frozen out of regional diplomacy on the highly consequential war in Gaza on account of his public defense of Hamas. He would welcome the chance for high-profile engagement with the United States under a second Trump term.

Turkey has other things to look forward to in a second Trump White House. Erdoğan’s son-in-law had famously gotten along with Trump’s son-in-law and former advisor Jared Kushner, and the two presidents had pledged to boost U.S.-Turkish trade and investments to an ambitious target of $100 billion. Much like Orbán, Erdoğan has also built close relations with Putin and benefited from Western sanctions against Russia by becoming a critical entrepôt. There is the hope that Trump’s re-election might be good for Turkish business interests and increase Turkish trade—even though the Trump administration’s America First economic policy has generally been anti-free trade and hiked tariffs on Turkish steel.

Trump’s return to the White House may also provide an opportunity for Turkey to expand its military control over Iraq and Syria—and settle scores with the U.S.-backed Syrian Kurds that Ankara considers to be terrorists. The issue has been a major irritant in Turkey’s relations with the United States and Turkish officials believe Trump was prevented by the U.S. bureaucracy (“the deep state”) from addressing the issue. Ankara is now hoping that Trump will be able to finish the job he started in 2019 and withdraw U.S. troops from Syria (“I held off this fight for … almost 3 years, but it is time for us to get out of these ridiculous Endless Wars, many of them tribal, and bring our soldiers home”). Such a move would allow Ankara to extend its territorial control inside the Syrian border and, as a bonus, consolidate nationalist voters around Erdoğan once again.

Ilham Aliyev

A stone’s throw away from Turkey, Azerbaijan’s Ilham Aliyev has been snubbing the Biden administration’s efforts to broker a peace treaty with neighboring Armenia, seemingly waiting for an opening to embark on his third military incursion against his neighbor. Having inherited power from his father, Aliyev has been keen to establish his own legitimacy by building a powerful military and reconquering Azeri territory that had been under Armenian control for decades. The 44-day war in September 2020 between the two states resulted in the deaths of several thousand Azeris and Armenians and resulted in Azerbaijan’s decisive victory, without so much as raising eyebrows from the Trump administration. U.S. officials now worry that Aliyev’s maximalist narrative might signal another offensive, this time cutting across Armenian territory to build a land bridge Baku wants.

Azerbaijan has been criticized by the international community and U.S. Congress for its human rights record, intolerance of domestic dissidents, and the treatment of Armenians and Armenian cultural heritage in the territories it has recently conquered. U.S. military assistance to Baku continues but often seems in peril due to congressional concerns regarding the country’s human rights record.

Aliyev would like a closer relationship with the West but, despite Baku’s growing role as an energy supplier to Europe, has not been invited to the White House. He would like the human rights issue taken off the table once and for all—and knows that this could only happen under Trump.

Strongmen, middle powers, and democracy

The Eurasian land mass has not been hospitable for democracy, and, with the exception of Georgia and Armenia, authoritarianism is rampant across Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the neighboring Middle East. The handful of instances when societies pushed for openings have been met with repression. With the exceptions of Israel and Turkey, democratic pluralism is lacking, and civil society remains weak in many countries. Iraq and Lebanon offer competitive political systems but fail their citizens in governance and accountability. Elsewhere it is lifetime leaders, kings, emirs, and elected autocrats.

This makes external relations critical for legitimacy and maintenance of power.

Leaders have different reasons to want a return of the Trump administration—often they are a combination of strategic interests and a desire to move away from a world where the vestiges of the post-World War II liberal order still set the tone. Those who prefer a Trump presidency are often middle powers run by strongmen who prefer the idea of a multipolar world—one where the United States is not the order-enforcing hegemon and where democratic norms are no longer the organizing principle for alliances. Trump, they hope, would expedite that trend.

It is no coincidence that pro-Trump regimes tend to be autocracies that fear liberal democracy at home and want to hedge by approaching great powers to protect their interests. These states prefer the type of transactional arrangements that the Trump administration is known for. From Saudi Arabia’s Mohammed bin Salman to Orbán, Aliyev, or Egypt’s Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi—whom Trump affectionately called “my favorite dictator”—middle powers also prefer a world in which democracy is not part of the global conversation and they are not lectured on human rights.

Of course, the 2024 U.S. elections will not be decided by Eurasian strongmen or Middle Eastern autocrats, but by the American people (or rather, Americans in key presidential swing states). Yet who they choose will have massive resonance beyond America’s borders at a time when democracy is in decline and a sense of cynicism permeates international ties. The elections can preserve the world of rules and alliances that America has tried to enforce for much of the past century or accelerate the transition away from the age of liberalism, toward a post-American order.

The latter, undoubtedly, is what autocracies want.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why do Europe’s strongmen love Trump?

For Viktor Orbán, Vladimir Putin, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Ilham Aliyev, and others, a second Trump term provides strategic openings and a dismantling of a liberal order that troubles their ties with the West.

April 5, 2024