This paper is excerpted from the 2018 Annenberg Lecture, delivered by the author at the University of Pennsylvania on Nov. 15, 2018.

Introduction

At a summit of international business leaders recently, I was surprised how often the discussions turned to the impact of the internet on liberal democratic values, including capitalism. Populism, nationalism, protectionism, Brexit, Trump, the rise of the alt-right, the call for socialism, and the seeming success of government-managed markets were all attributed—at least in part—to how the internet has eliminated many of the rules that delivered stability for the last century.

A “liberal democracy” does not apply the word “liberal” as we do in American politics. A liberal democracy is a representative democracy of free and fair elections, and the rule of law applied to equally protect all persons. Until recently, it has been on the rise throughout the world. Democratic capitalism is a free market operating within guardrails established by such a liberal democracy.

What I was hearing from the business leaders was that new technology and the internet create an economic and social instability that plays into the hands of those at the extremes—extremes of both political thought and marketplace dominance.

At the political level, the digital engine that is driving economic and social instability also provides the tools to exploit the resulting dissatisfaction so as to threaten liberal democratic capitalism. Populism from the right can tend toward authoritarianism, while populism from the left can tend toward socialism. In the marketplace, technology has delivered a different type of extremism: a handful of companies with unfettered dominance over key components of economic activity. The internet, a decentralized collection of interconnecting networks, has created new centralized powers that siphon, aggregate, and manipulate personal information to create bottlenecks to the operation of free and open competition.

Populism from the right can tend toward authoritarianism, while populism from the left can tend toward socialism. In the marketplace, technology has delivered a different type of extremism: a handful of companies with unfettered dominance over key components of economic activity.

The internet started out with the hope of being the great democratizer by removing barriers to everything from the flow of news to local taxi service. While the networks of history had centralized economic activity, the distributed architecture of the internet would similarly distribute power away from central institutions. Unfortunately, that has not been the result. Companies utilize the distributed network to recentralize activity. Corporate digital autocrats collect personal information and exploit it to control markets. Political digital autocrats use the internet to spy on their citizens and target attacks on the democratic process.

I. Technology has done this before

That the effects of new technology cause such upheaval should not surprise us. Technological change previously caused similar—if not greater—destabilization; both economic and political. The technology-driven upheavals of the late 19th and early 20th centuries shaped the world from which our new technology is departing. The challenges of that time echo in the reality that confronts us today.

That the effects of new technology cause such upheaval should not surprise us. Technological change previously caused similar—if not greater—destabilization; both economic and political.

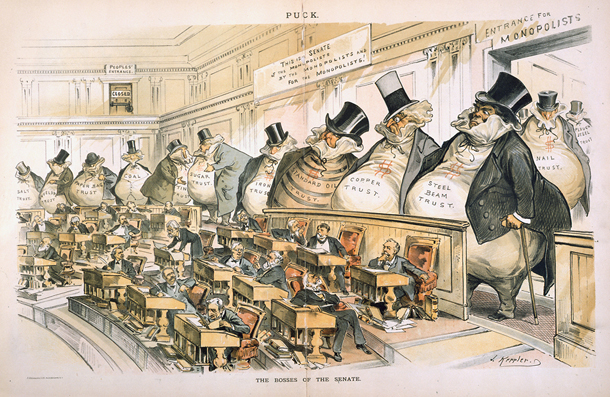

A couple of decades after the Civil War, the United States entered an era dubbed “The Gilded Age.” It was Samuel Clemens—Mark Twain—who gave us the term. In an 1873 novel, co-written with his friend Charles Dudley Warner, the duo satirized the economic excesses, personal greed and political corruption of the time. The novel’s title, “The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today,” was an inspired choice of words.

In Twain’s telling, the era wasn’t a “golden” age—something pure and solid like a bar of gold—rather is was a “gilded” age. To “gild” is to cover something of lesser value with a coat of gold to make it look like what it is not. In Twain’s telling, the era was one in which such a superficial covering disguised a more base reality.

The Gilded Age was a time in which technological innovation drove wonderful new industrial products that improved individual lives, while at the same time creating great wealth and accompanying economic inequality. It was a period of market dominating companies and citizen and journalistic revolts against their control. It was also a period marked by claims of “fake news” and by the election of two presidents who failed to win the popular vote. (Hayes in 1876 and Harrison in 1888.)

The similarities between this era and today bring forth another great Twain observation: “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.” Today we live in the new Gilded Age: technology-driven innovations have again improved daily life while creating great wealth, inequality of circumstances, non-competitive markets, and viral deceit.

There is one more similarity between today and the original Gilded Age. Back then, the rules that governed the application of the new technology were made by a handful of industrial barons for their own benefit. The rules in the early internet era—the new Gilded Age—are being made similarly; this time by information barons.

The unbridled nature of the original Gilded Age eventually went too far. The result was a popular uprising and the representatives of the people stepping in to create a set of rules to serve the broad public interest over narrow private interests. We find ourselves at a similar crossroads today. Whether and how we step up to that responsibility is the challenge of our era … and of each of us.

Good policy is grounded in an understanding of history. We forget that liberal democratic capitalism succeeded because acting collectively, Americans caused their democratic institutions to protect consumers, workers, and the competitive marketplace. We forget that liberal democratic capitalism had to do battle against those who saw communism, socialism, or fascism as a better alternative. We forget that liberal democratic capitalism was preserved through the establishment of rules that inhibited its natural excesses.

In the industrial era, we discovered that the rules established for a mercantile-agrarian economy were no longer up to the task. Industrial scope, scale, and speed necessitated the establishment of guardrails to keep industrial capitalism on the right path. As we look at the new realities of the internet age, we need similar guardrails that will allow information capitalism to similarly succeed.

It is “an old pattern in American economic history,” historian John Steele Gordon explained, “Whenever a major new force—whether a product, technology, or organizational form—enters the economic arena, two things happen. First, enormous fortunes are created by entrepreneurs who successfully exploit the new, largely unregulated niches that have opened up. Second, the effects of the new force run up against the public interest and the rights of others.”1

New technology opens new niches for which there are no rules because the niche never before existed. Those who saw the niches and determined how to open them deserve to be rewarded. But when the exploitation of those niches collides with the common good, then the people have the right to insist on rules to protect the broader public interest.

Thus, it is appropriate to ask the question, “Who makes the rules in the new Gilded Age?” Who is it that stands up for the public interest and the rights of others?

At the time of the original Gilded Age, it was the industrial barons who made the rules. That is, until the people’s representatives stepped up to do their jobs. Today, in the new Gilded Age, it is the internet barons who make the rules. Unfortunately, the parallel ends there. Neither the Republican-led Congress, nor the Trump Administration has stepped up to their responsibility to establish new rules for our new time.

II. Listening to TR

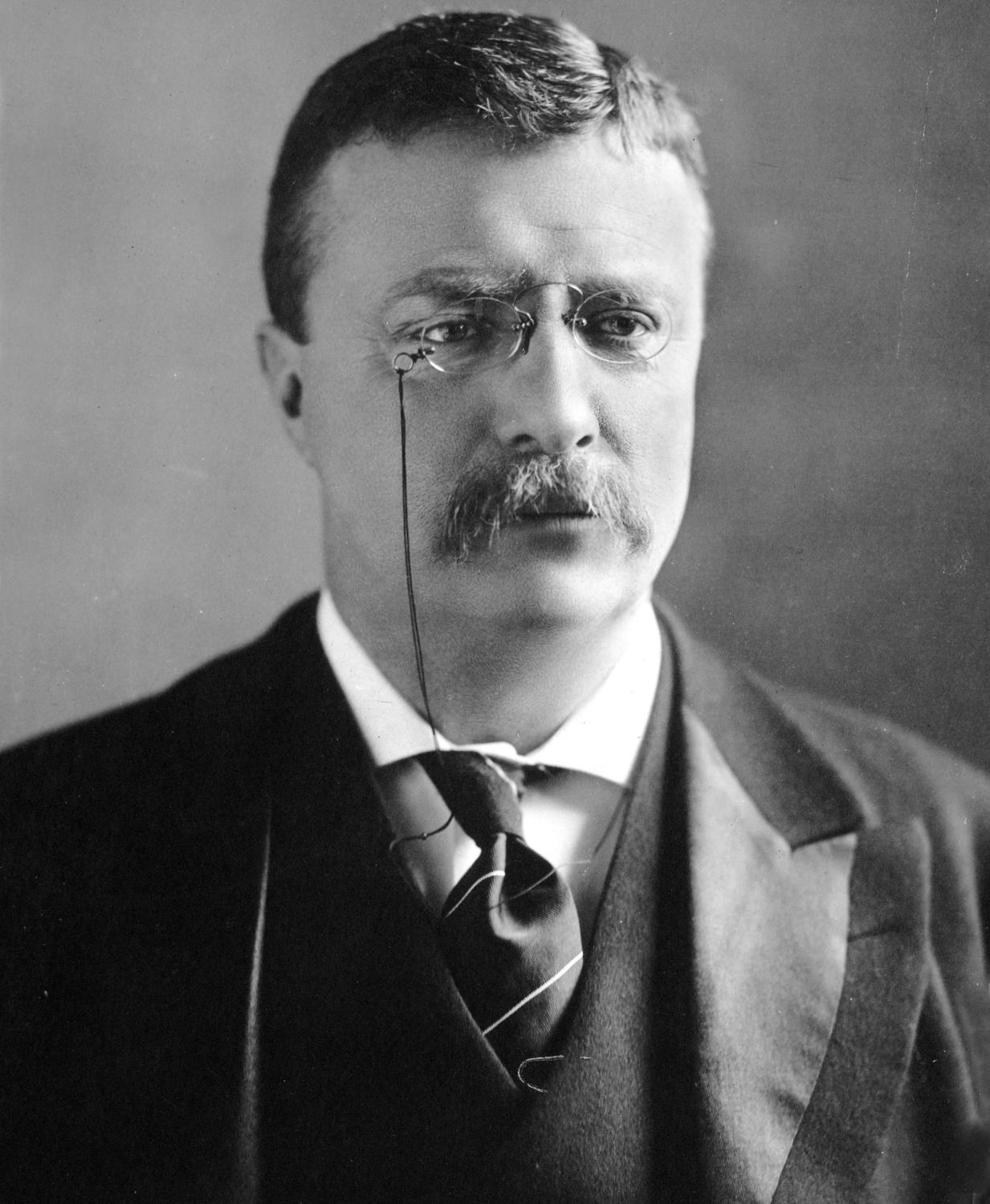

So, let’s step back in time for a moment, into that earlier Gilded Age. Specifically, let’s go to the morning of March 4, 1905 in the nation’s capital. As is typical for the early spring in Washington, the day saw a struggle between snow and daffodils. It had snowed the day before; but on this day, under a bright 45-degree sun, the president of the United States stood before the Capitol to take the Oath of Office. Theodore Roosevelt, who had become the surprise president upon the death of William McKinley four years earlier, was now the duly elected chief executive of a country at the height of the Gilded Age.

Roosevelt addressed the dichotomy of economic expansion and the abuse of the power that had accumulated to a few as a result. While the industrial economy had produced “marvelous material well-being,” he said, it also generated “care and anxiety” that were “inseparable from the accumulation of great wealth.”2

Speaking for the average citizen buffeted by technology-driven, market-concentrating change, Roosevelt observed, “Modern life is both complex and intense, and the tremendous changes wrought by the extraordinary industrial development of the last half century are felt in every fiber of our political and social being.”

It is a message that could have been delivered today.

Roosevelt concluded with a message that should be delivered today. It was time for the nation to “approach these problems with unbending, unflinching purpose to solve them aright.”

The economic powerhouses of which Roosevelt spoke were of two types: those that built the networks that connected the nation, and those that used the networks. The economic powerhouses of the digital era have the same construction: dominant providers of internet access and the dominant digital platforms that ride on them.

Railroads were the first high-speed network. By transporting raw materials to a central point for factory-based conversion into products, the railroad enabled the industrial revolution—just as high-speed internet connections have enabled the information revolution. In an observation as applicable now as it was then, one historian wrote, “Being run by human beings, the railroads, naturally, did not hesitate to exercise their market power to their own advantage.”3

The railroads then enabled new economic giants, just as the internet has. When Gustavus Swift developed the refrigerated railroad car in 1878, his company did to local butchers what Google would do to the local advertising business over a century later. Slaughtering at scale in Chicago abattoirs was significantly less expensive than one-off local butchers doing the same thing. Add to this the savings from transporting only the edible cuts of beef rather than the whole cow, and Swift redefined the American dinner plate while destroying a cornerstone of local economic activity.

Today’s economic activity is built on digital code. Digital information is the most important capital asset of the 21st century. Typically, Gilded Age assets were hard assets: industrial products that ended up being sold. Today’s economy runs on the soft assets of computer algorithms that crunch vast amounts of data to produce as their product a new piece of information. The business of networks like Comcast, AT&T, and Verizon, and of platform service providers like Google, Facebook, and Amazon is not just connections or services, but the digital information about each of us that is collected by those activities and subsequently reused to target us with specific messages.

Roosevelt’s explanation that the innovative use of new technology is “inseparable from the accumulation of great wealth” has also proven true in the new Gilded Age. A 2015 study concluded, “Only the ‘Gilded Age’ at the beginning of the 20th century bears any comparison” to the extraordinary wealth creation of the last 35 years.4 At the height of the first Gilded Age, the top decile commanded more than 45 percent of the gross income in the United States. Today, the top decile of earners commands more than 50 percent of income.5

At the height of the first Gilded Age, the top decile commanded more than 45 percent of the gross income in the United States. Today, the top decile of earners commands more than 50 percent of income.

This is not a condemnation of the entrepreneurs who built the digital economy. The risk-taking and the vision necessary for innovation deserves to be rewarded. It is, however, a commentary that trickle-down economics has failed to share those rewards with the rest of the population.

The former CEO of Sears, Arthur Martinez, has explained that only a few decades ago, “the people who produced or sold the product were more central than the people in the corporate suite.” At Sears—a powerhouse in its day like Amazon is today—the company’s profit sharing subsidized employee stock purchases. This meant, according to The New York Times, that 50 years ago, a typical Sears salesman, “could walk out of the store at retirement with a nest egg [of Sears stock] worth well over a million dollars in today’s dollars.” “If Amazon’s 575,000 total employees owned the same proportion of their employer’s stock as the Sears workers did in the 1950s, they would each own shares worth $381,000,” the Times calculated.6

Teddy Roosevelt echoes again: “There can be no real political democracy unless there is something approaching economic democracy,” he warned.7

Which leads us to a foundational question. Amidst all the industrial upheaval, non-competitive markets, and economic inequality of the Gilded Age, government did little to address the root issues. Today is even worse. Government began to address the issues of new technology’s impact during the Obama Administration. As Chairman of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), I played a role in some of those activities. However, the rules we established—for example, to protect personal privacy and guarantee open access to the internet—the Trump Administration and Republican-led congress quickly repealed.

One must ask—of today and of the original Gilded Age—why did leaders ignore the obvious need for rules to provide stability and certainty?

In “Age of Betrayal,” a comprehensive analysis of the Gilded Age, author Jack Beatty reflected on this question. “A student of the Gilded Age confronts a mystery,” he wrote, “What reverse alchemy transformed mass enthusiasm [built around specific political issues] into policies disfavoring the masses?” The answer, he concluded, was the “politics of distraction.”8

In the Gilded Age, “The parties exploited sectional, racial, cultural, and religious cleavages to win office,” Beatty judged. “Then [they] turned government over to the corporations.” The mandate of the people was achieved by focusing on single issues designed to arouse a target base. Once in power, however, the people’s mandate was not used to protect the people who granted the power in the first place.

In the new Gilded Age, the politics of distraction is aided and abetted by the ability of digital networks and algorithms to target the distracting messages.

Today, we hear some of Twain’s historical rhymes. In the new Gilded Age, the politics of distraction is aided and abetted by the ability of digital networks and algorithms to target the distracting messages. It is perverse that what the digital companies call building a “community” actually enables the opposite: to divide communities into tribes that are then organized to maximize distraction from what is not being done.

III. “Unending, unflinching purpose”

If we are to import TR’s challenge to “approach these problems with unbending, unflinching purpose to solve them aright,” what should be done?

Once again, let us turn to Mr. Roosevelt.

Only a few weeks before his inaugural remarks, Roosevelt opened his campaign for meaningful railroad regulation with a speech at the Union League Club of Philadelphia. While his focus may have been on the networks, his observations are of general applicability:

Neither the people nor any other free people will permanently tolerate the use of the vast power conferred by vast wealth, and especially by wealth in its corporate form, without lodging somewhere in the government the still higher power of seeing that this power, in addition to being used in the interest of the individual or individuals possessing it, is also used for and not against the interests of the people as a whole.

Today, just like a century earlier, the first step in rebalancing between the people and the powerful begins with oversight of the dominant network. This time that network is the one that provides internet connections to homes and offices. The struggle over what has become known as “net neutrality” has at its core the very issue TR identified in Philadelphia: the necessity to “keep the great highways of commerce open alike to all in reasonable and equitable terms.”9

Today, the “great highways of commerce” are the wired and wireless networks that deliver high-speed connections to the internet. Since the early days of this century, a debate has raged over the nature of public oversight of these new digital pathways. Both Republican and Democratic FCCs proposed oversight policies—and the companies fought them all. Every time the FCC would put a policy in place, a network would file suit to block it. The networks won most of those challenges.

In February 2015, I asked the FCC to vote on an Open Internet Rule declaring that those providing internet access to homes and offices were common carriers that must provide nondiscriminatory access to their network. By a contentious 3-2 party-line vote, the proposal was adopted. Most importantly, when the networks’ inevitable court challenge followed, the same court that had struck down an earlier decision upheld our decision—twice.

For the following almost three years, the Open Internet Rule proved that the internet, the most crucial tool for innovation, creativity and access in over a century, could remain free and unencumbered for the people who need it most—while allowing network companies to flourish.

When Congress passed the railroad regulation bill in 1905, the railroads launched what Doris Kearns Goodwin described as, “a sweeping propaganda campaign to turn the country against regulation.”10 The network giants of the time argued that, “disaster would follow if the government ‘should meddle’ in the complex business of network decisions.” They further asserted, “The laws already on the books were sufficient to deal with any difficulties.”11

The same arguments were dusted off and replayed during debate on the Open Internet Rule. The networks’ lobbying propaganda found a receptive regulator after the surprising result of the 2016 presidential election. At the urging of the industry, Donald Trump named as the new FCC Chairman the Commission’s most vocal opponent of the Open Internet Rule. Within days, the new Republican FCC began walking away from Republican Theodore Roosevelt’s vision of a “still higher power” acting in behalf of the people.

Pre-Roosevelt, efforts at railroad regulation “were little more than political cover for allowing railroads to do as they pleased,” John Steele Gordon observed.12 The Trump FCC followed the same pattern with regard to the essential network of the 21st century by repealing the Open Internet Rule. Then, the FCC reprised the 1905 railroad propaganda by claiming that, “The laws on the books were sufficient to deal with any difficulties.” More than simply repealing the existing Open Internet Rule, the FCC—the federal agency created to oversee the public interest obligations of essential electronic networks—walked away from its responsibility, claiming it had no authority, and asserting the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) could act if anything untoward were to happen.

The Trump FCC’s action was the culmination of the internet providers’ grand plan. In 2013, The Washington Post had reported, “Here’s how the telecom industry plans to defang their regulators.”13 That article explained, “telecom giants including Verizon, AT&T, and Comcast have launched multiple efforts to shift regulation of their broadband business to other agencies that don’t have nearly as much power as the FCC.”

On December 14, 2017, the Trump FCC fulfilled the network’s lobbying goal. By a 3-2 party-line vote, the Commission threw out the Open Internet Rule. In keeping with the networks’ strategy, the FCC also announced it would no longer be responsible for oversight of the most important network of the 21st century.

The first answer to the question “Who makes the rules in the new Gilded Age?” was answered—at least insofar as the networks were concerned.

IV. Rules for those who ride the networks

One of the other arguments made by the networks as to why they should not be regulated was that it “wasn’t fair” that they should exist under public interest rules while the companies that use the network—service platforms like Google and Facebook—were making huge profits because they had no such rules. That is because Google,14 Facebook, et al do not provide internet access services, so oversight of their activities falls to the general responsibility of the Federal Trade Commission over unfair or deceptive acts or practices in the marketplace.

While the FTC has brought after-the-fact adjudicatory action against the platform companies for deceptive practices—principally, not telling consumers about their collection of private information—the agency has heretofore determined it lacks statutory authority to dictate broad going-forward rules. The FTC can typically act only after harm has been done and the horse is out of the barn. This has left the people who run the platform companies free to make their own rules.

Such self-directed rule-making especially impacted two issues: the privacy of the personal information of each of us, and the disappearance of a competitive market for digital services.

The rights of individuals regarding their personal information is rapidly becoming a 21st-century civil rights issue. We have emerged into an era where the technology to collect and aggregate personal information has sped past the law.

The rights of individuals regarding their personal information is rapidly becoming a 21st-century civil rights issue.

Consumers know they have lost control of their personal information. A 2017 survey found 70 percent of Americans lacked confidence that their personal data is private and safe from distribution without their knowledge.15

Returning to citizens the control of their information has been embraced by both the left and right of the political spectrum. Alt-right political strategist Steve Bannon describes it as the recovery of each individual’s “digital sovereignty.” He cites it as one of the three principles that will drive a forthcoming populist rage.16 The political left has adopted a similar theme, calling it “digital feudalism.” In Medieval times, feudal lords confiscated the output of the serfs—their labor; today, digital lords confiscate the output of citizens—their information.

There can be no doubt about the wondrous new capabilities that have been made possible using digital information. From ordering a pizza, to conducting medical research without test tubes and lab rats, we are significantly better off because of the data-based innovations the internet has made possible. While applauding the success delivered by the innovative use of personal data, however, we cannot be blind to how the rules are being made by those with the incentive to first look out for their business interests.

One of the company-made rules is to lock away behind digital walls the vast trove of information they gather about each of us. This practice allows the company to leverage your personal information to create a dominant anti-competitive position in the marketplace.

The more information a company has, the more precise its targeting can be, the harder for a competitor to gain a foothold, and the more that can be charged. Thus, the companies developed practices that allowed them to not only maximize information collection, but also to deny its access to others.

The same platform companies that championed the Open Internet Rule so the networks could not create a bottleneck that could shut them out, oppose applying similar openness rules to the data they have siphoned from consumers and locked away to create their own bottleneck.

The early developers designed the internet to be an open network. After creating the internet, the open development process continued for the network’s technical standards but fell apart for the commercial operation of those that use it. The very same companies that found in the open standard the niche of opportunity, walked away from that openness in order to create their own rules built around locking everything behind the high walls of discrimination.

Under classic economic theory, the low costs and high profits enjoyed by internet platforms should attract competitors, and that competition should protect consumers and market viability. The way the companies have written the rules, however, allows them to hoard the digital information siphoned from consumers and use that hoard any way they wish—including as a tool to keep out competitors.

The nondiscriminatory openness that created the world’s most important network thus falls prey to gatekeepers whose business plan relies on siphoning personal information, aggregating great quantities of it to enhance targeting, and then denying access to those assets in order to discriminate. Because they can make their own rules, the platform services that today rely on the internet to collect personal information and deliver services have reconstructed the kind of walled gardens the technology of the internet was designed to abolish.

This is the second answer to “Who makes the rules in the new Gilded Age?”

V. Need for new rules

The digital companies are not bad actors—they have just been given free rein over their behavior and have taken advantage of that lack of oversight. They have acted in accord with human nature and economic self-interest. Nobody expects them to act like the Red Cross.

The digital companies are not bad actors—they have just been given free rein over their behavior and have taken advantage of that lack of oversight.

We have seen actors on a stage like this before. We know that in that play, the establishment of rules helped preserve industrial capitalism. The protection and preservation of internet capitalism calls out for a similar script.

Once again, we turn to Theodore Roosevelt for insight and inspiration. At that meeting in Philadelphia, only a few weeks before his inauguration, he spoke about the same topic we are discussing today. “The great development of industrialism,” he said, “means that there must be an increase in the supervision exercised by the government over business enterprises.” Then he appealed to American business to work with him. “This supervision should not take the form of violent and ill-advised interference,” he pledged. But, then he cautioned, “assuredly there is danger lest it take such form if the business leaders of the business community confine themselves to trying to thwart the effort at regulation instead of guiding it aright.”

That was a pretty clear message, but Roosevelt continued, saying that the responsible business leaders of America should…

…[L]ead in the effort to secure proper supervision and regulation of corporate activity by the government, not only because it is for the interest of the community as a whole that there should be this supervision and regulation, but because in the long run it will be in the interest above all of the very people who often betray alarm and anger when the proposition is first made.

The corporate leaders ignored that advice. What followed this speech was a vigorous and hard-fought debate over the rules for industrial capitalism. We should not delude ourselves that our challenge will be any easier or less arduous.

Interestingly, however, the kind of meaningful rules that should govern the most powerful and pervasive platform in the history of the planet17 are actually hundreds of years old. They are embedded in the principles of common law. Such principles are simply that companies have responsibilities: a “duty of care” not to cause harm, and a “duty to deal” to ameliorate the consequences of monopoly bottlenecks. Such concepts were at the heart of industrial era regulation. In today’s world of internet-driven change, these principles remain unchanged.

The harvesting of personal information—often without the individual’s knowledge—infringes on the sovereignty of the individual and their personal privacy. Just as the government established rules post-Gilded Age to protect the collective good by assuring pure food and drugs and clean air and water, we now have a collective interest in overseeing how the internet allows companies to collect and exploit personal information. Internet companies—both service platforms and the networks that deliver them—should have a “duty of care” as to the effects of their actions on personal privacy.

The companies and the FTC have focused on what is called “transparency”—the disclosure of what the companies are doing to collect and use your information. This is accomplished by the so-called “privacy policies” of each company. In Orwellian doublespeak, these “privacy policies” are made to sound as though they are protecting privacy, but they are actually about gaining permission to violate your privacy. Far from protection, they are extortion; a list of privacy taking permissions the companies want you to agree to in order to receive their service.

At a standard reading rate, it would take 76 eight-hour days—almost four months—to read the policies of the websites visited by the average American.

Each company makes the rules they develop easily available. The companies argue this fully informs the consumer. Here, however, is where the rubber of “make your own rules” transparency meets the road. According to a Carnegie-Mellon study, the median length of such policies for the top 75 websites is 2,514 words. At a standard reading rate, it would take 76 eight-hour days—almost four months—to read the policies of the websites visited by the average American.18 Even more important, because these rules are unilaterally made by the companies, they can be—and are—changed whenever the company wants. All the companies have to do is tell you they’ve unilaterally changed the rules, and the charade begins anew.

Certainly, transparency is better than no transparency. But it is not a singular solution to protecting the privacy of Americans. Too often, it is nothing more than air cover for internet companies making the rules by themselves. Telling consumers what you are about to do to them is not justification for the act itself. Informing consumers about the policies the companies have unilaterally established is not absolution for the practices those rules allow.

Specific disclosure as to what data is being collected, by what means, how the data is used, and to whom it is available are essential to the meaningful enrichment of any transparency. Most important, however, is giving the consumer control over their own information. This means consumers should have up-front opt-in control of what information is collected and how it is used. Consumer control of his or her information should also include the ability to move that information to a different platform or service.

In addition to consumer control and corporate transparency, a “duty of care” begins with protecting personal information as a forethought, not an afterthought. Mark Zuckerberg was candid in his congressional testimony when he said the design of digital platforms often proceeded without consideration of the effect of that design. “We didn’t take a broad enough view of our responsibility,” he told the United States Senate.19

What has been missing thus far in the internet era has been exactly that kind of planning ahead to identify the possible effects of a specific digital activity. Asking the question, “Do we understand the implications on personal privacy of what we are building?” should be a threshold question in the creation of digital services.

Transparency, control, and forethought are implementations of the “duty of care.” It underlies the legal principle of negligence and the expectation of reasonable care being exercised to anticipate and mitigate the potential harm an activity might impose.

The personal information that is collected has also been cartelized to create new market-dominating anti-competitive forces. The data economy is no different from earlier economies where human nature and economic instinct created market-controlling bottlenecks. One of the basic concepts developed in the common law was to open access to bottlenecks through a “duty to deal.”

The data economy is no different from earlier economies where human nature and economic instinct created market-controlling bottlenecks.

Bottlenecks and the attempt to exploit them are as old as time. In Medieval times, for instance, roadside inns and river ferries were examples of such bottlenecks. The common law held, however, that such fundamental activities had the responsibility to accept all comers, not just those the proprietor chose to serve. The internet is the 21st-century river ferry: a fundamental activity upon which depends the economic well-being of others. Similarly, just as the ancient innkeeper controlled access to food that should not be denied others, the digital platform companies control access to the data sustenance of the digital economy.

For networks, the “duty to deal” means a prohibition on discriminatory access. The ferryman’s duty to carry something across the river is no different than the telegraph, railroad, and telephone networks’ duty to carry all comers indiscriminately. It is also the heart of net neutrality.

For platforms such as Google and Facebook, the “duty to deal” means the inability to hoard a fundamental asset to the detriment of society. The Medieval innkeeper was not required to feed travelers for free, but he was required not to withhold the sustenance he had collected and prepared. The innkeepers of the internet era are the platform companies that collect, aggregate, and allocate digital information; like their analog predecessors, they are free to profit from their services, but the services must be openly available.

For 600 years, the simple, yet irrefutable concept that the proprietor of a fundamental asset has a duty to make it available has stood the test of time and technology to remain valid today. While digital technology has redesigned the nature of bottlenecks, nothing has repealed the incentive behind the creation of such bottlenecks, nor the public interest remedy to their abuses.

VI. Old concepts for new times

It is both fascinating and practicable that centuries-old solutions could help us deal with the realities of the digital era. Companies have a responsibility to act to protect the consumer’s best interests—a duty of care—and a responsibility to not act as a marketplace choking bottleneck—a duty to deal. To oversee that, government has a duty to implement rules that turn these responsibilities into required practices for the benefit of the common good.

We should celebrate the many remarkable developments made possible by the companies of the digital economy. At the same time, however, it is time to reassert old truths and re-establish in law and regulation traditional duties to protect citizens and the competitive market. Such rules can ultimately benefit the companies and internet capitalism in the same way that past public policy decisions permitted industrial capitalism to flourish.

If we reassert public interest rules over private interest rules, we will have taken an important and essential step toward the preservation of liberal democratic capitalism.

If we do this—if we reassert public interest rules over private interest rules—we will have not only answered “Who makes the rules in the new Gilded Age?” but we also will have taken an important and essential step toward the preservation of liberal democratic capitalism.

-

Footnotes

- John Steele Gordon, “Regulators Take On Silicon Valley, as They Did Earlier Innovators,” The Wall Street Journal, April 17, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/regulators-take-on-silicon-valley-as-they-did-earlier-innovators-1524005477.

- Inaugural Address of Theodore Roosevelt, Yale Law School Library, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century?troos.asp.

- John Steele Gordon, An Empire of Wealth, Harper Perennial, 2004, p. 236.

- UBS and PwC, Billionaires, 2015.

- Emmanuel Saez, “Striking it Richer: The Evolution of Top Incomes in the United States,” University of California at Berkeley, 3 September 2013, https://emi.berkeley.edu/~saez/saez-UStopincomes-2012.pdf.

- https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/23/business/economy/amazon-workers-sears-bankruptcy-filing.html.

- Theodore Roosevelt, “Outlook,” November 18, 1914, Mem. Ed. XIV, 220; Nat. Ed. XII, 237, http://www.theodoreroosevelt.org/site/c.elkSidOWliJ8H/b.9294761/k.C857/Index_D.htm.

- Jack Beatty, Age of Betrayal, Vintage Books, 2008, p. 221.

- Alfred Henry Lewis, ed., A Compilation of the Messages and Speeches of Theodore Roosevelt 1901-1905, Bureau of National Literature and Art, 1906, pp. 550-54.

- Doris Kearns Goodwin, The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism, Simon & Schuster, 2013, p. 448.

- Ibid.

- Gordon, p. 237.

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-switch/wp/2013/09/12/heres-how-the-telecom-industry-plans-to-defang-their-regulators/?utm_term+.95aeefc57fac.

- In a few cities, Google Fiber offered a digital network service and that network was regulated.

- https://consumerreports.org/privacy/americans-want-more-say-in-privacy-of-personal-data/.

- https://breitbart.com/london/2018/03/23/bannon-governments-debase-citizenship-central-banks-debase currency-state-capitalist-tech-firms-debase-personhood/.

- A wonderfully alliterative description from my friend Blair Levin.

- https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2012/03/reading-the-privacy-policies-you-encounter-in-a-year-would-take-76-work-days/253851/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/11/business/zuckerberg-facebook-congress.html.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).