As U.S.-based card payment companies like American Express, MasterCard, and Visa strive to set up shop in China, Chinese consumers are increasingly using their mobile phones to buy goods and services. In effect, the country has leapfrogged from cash to mobile payments, bypassing the payment cards system.

Furthermore, mobile payments constitute just one of seven key markets for China’s booming fintech industry. (Fintech is short for “financial technology” and refers to the application of technology within the financial services industry.) Other areas include online lending, consumer finance, online money-market funds, online insurance, personal financial management, and online brokerage. Of the 27 fintech “unicorns”—fintech startups with valuations exceeding $1 billion—in the world, nine are Chinese (including one from Hong Kong) and 12 are American.

Behind China’s fintech miracle lies the country’s unique technology ecosystem: a tech-savvy population, an underdeveloped banking industry, and an initially relaxed regulatory environment. While per-capita income in China remains low—$4,044 in 2017—the country’s rapid urbanization process has spurred the growth of a large middle class. In 2016, approximately 225 million households earned between $11,500 and $43,000 a year—a group rivaling the size of the entire U.S. population of 323 million. As of December 2017, China had 772 million internet users, or more than the entire population of Europe. And yet, that figure represents only 55.6 percent of China’s population. Perhaps most significant of all, more than 95 percent of China’s internet users—or 772 million people—access the web via a mobile device.

Figure 1: China’s internet users total 772 million

Figure 2: Over 95 percent of China’s internet users are on mobile

China’s remarkably unsophisticated banks stand in marked contrast to its well-developed technological infrastructure and soaring demand for financial services. For a long time, commercial banks in China, which are mostly state-owned, have focused mainly on servicing Chinese state-owned enterprises, neglecting the growing financial needs of small-to-medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and ordinary Chinese people with rapidly accumulating wealth. According to World Bank data, in 2014 only 9.6 percent of Chinese adults had access to credit from a financial institution, which includes not only banks, but also credit unions, cooperatives, and microfinance institutions. Similarly, according to the World Bank’s 2012 Enterprise Survey, Chinese SMEs received less than 25 percent of the loans extended by Chinese banks despite the fact that SMEs accounted for over 60 percent of China’s GDP and 80 percent of urban employment. This discrepancy in bank lending was attributed to the lack of qualified collateral and credit histories among SMEs.

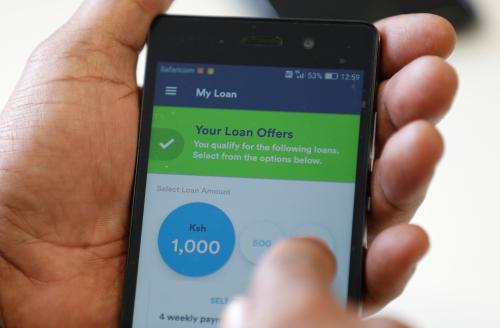

Fintech firms, noticing this surplus of underserved individuals and SMEs, have stepped in to fill the void. Mobile payments and online lending, which directly address consumers’ spending and credit demands, are the two most prominent sectors in the Chinese fintech industry.

Mobile payments

The numbers speak for themselves when it comes to Chinese mobile payments. In 2016, Chinese consumers spent approximately $22.8 trillion (RMB 157.55 trillion) through mobile payment platforms, far exceeding the volume of transactions in the United States ($112 billion). Over 90 percent of that sum stemmed from mobile payment apps that belong to China’s two biggest tech conglomerates: Alibaba’s Alipay (54 percnt) and Tencent’s TenPay (37 percent).

Figure 3: China’s mobile payments business has grown at a three-digit annual rate over the last five years

Alibaba launched Alipay in 2004 as a PayPal-type service to facilitate transactions on its e-commerce website Taobao. It quickly grew into the largest platform for online transactions and remained the dominant player until a decade later, when its market monopoly was interrupted by Tencent, another tech giant in China best known for its social media platform WeChat with 889 million active users. Tencent’s “Weixin Pay” burst onto the scene with digital hongbao, or “red envelope”—a reference to the stationery commonly used for cash gifts during the Chinese new year. The ability to send hongbao online via WeChat accounts revolutionized a centuries-old practice. This past year, approximately RMB 46 billion was exchanged via digital hongbao over the six-day holiday period.

Competition for market share has propelled innovations that connect online payments with face-to-face retail transactions. QR codes, a type of matrix barcode, have been key in facilitating the offline-to-online interaction and are widely used in China’s retail businesses, from street food vendors to Starbucks. QR codes can be used in either direction: A shopkeeper can display a code that customers scan with their mobile phone to initiate a payment, or a customer’s WeChat or Alipay account can generate a unique, transaction-specific code that a retailer scans to complete a transaction. In either case, the mobile phone acts as a kind of payment card. Money transfer between parties is also as simple as sending a text message.

Unlike the disaggregated mobile payments market in the United States—where PayPal and Visa Checkout are used for online shopping, Apple Pay and Android Pay serve as mobile-phone wallets, and Venmo and Facebook Messenger are common for transferring money between friends—single platforms in China integrate all of these functions. The aggregation provides greater convenience to users while leaving little space for new entrants to compete with incumbents.

Online lending

China has become the global leader in online lending, accounting for three-quarters of the global market. The majority of China’s online lending is peer-to-peer (P2P). Online lending platforms connect potential borrowers with lenders who are seeking returns higher than bank-offered interest rates. As P2P lending platforms have taken shape, private capital that once sat idle due to limited investment opportunities has started to pour in. P2P lending platforms mushroomed from only 200 in 2012 to more than 3,000 in 2015. P2P loans reached RMB 252.8 billion by the end of 2014, then quadrupled to RMB 982.3 billion in 2015.

Absence of regulation sparked the boom but also gave rise to a market brimming with scams and high-risk financial models. The most headline-grabbing case was Ezubao, a platform that lured investors with promises of double-digit annual returns. It attracted $7.6 billion from nearly one million users in just 18 months before it was identified as a Ponzi scheme, with more than 95 percent of its borrowers being fictitious. In 2016, about 1,300 platforms were pegged as problematic, and over 900 closed by the end of the year. While some closures were due to legitimate mergers and acquisitions, many shutdowns were the result of new regulations. The new rules bar online lenders from guaranteeing principal or interest on loans they facilitate. They also cap the size of loans at RMB 1 million for individuals and RMB 5 million for companies, and they force lenders to use custodian banks—a requirement only a fraction of the industry has met so far. In November 2017, approvals for all online lending companies were halted, a measure that further chilled this fast-growing sector.

Figure 4: The total number of P2P online lending platforms plummeted in 2016, even though transaction volume more than doubled that same year

Credit reporting system

The risk of fraud in the credit market has moved Chinese authorities to impose stricter regulations and establish a national credit reporting system (zhengxin xitong, 征信系统). This system could also help narrow the credit gap by facilitating lending to hundreds of millions of Chinese who want access to small business loans or consumer credit, but who have no collateral or financial history. Yet, the Chinese government’s national credit agency, the Credit Reference Center of the People’s Bank of China has fallen short in achieving such a system. Although it claims to have credit profiles for over 20 million businesses and over 850 million individuals, only a quarter of China’s population of 1.4 billion has a documented credit history. In comparison, nearly 90 percent of the adult population in the United States has a credit score.

With reams of user data, China’s largest fintech firms are ahead of the curve in setting up their own credit measurements. Alibaba, the world’s largest e-commerce firm, rolled out Sesame Credit in 2015. Sesame Credit has direct access to data related to the more than 500 million consumers who use Alibaba’s Taobao and Tmall marketplaces on a monthly basis, as well as payment histories of the more than 400 million registered users on its mobile payment app Alipay. Sesame Credit assigns users a score ranging from 350 to 950 based on five criteria: credit history, online transactional habits, personal information, ability to honor an agreement, and social network affiliations. Those with high credit scores have access to special privileges, including online credit, express service at hotels and airports, deposit waivers on rentals, and expedited visa applications to Singapore and Luxembourg. Tencent stepped onto the credit-scoring battlefield this past August when it introduced Tencent Credit, which also derives scores from five indices. (Tencent Credit has not yet explained how individual criteria are weighted.)

In the United States, the majority of lenders rely on FICO scores to determine a borrower’s creditworthiness. An individual’s FICO score is based on his or her credit history, which includes factors like credit utilization, on-time payments, and average age of accounts. By contrast, Sesame Credit and Tencent Credit draw on the two tech giants’ massive pool of user data to assign credit scores, incorporating criteria like a borrower’s social network, online shopping history, educational background, income level, and profession.

Table 1: Comparing Sesame Credit Score, Tencent Credit Score, and FICO Score

Alibaba and Tencent were only two of the eight technology companies the Chinese government tapped to develop pilot programs in consumer credit reporting in 2015. So far, none of the eight firms has been granted a government license. Companies have developed their credit systems almost like loyalty programs—customers gain access to special promotions and products as their credit scores increase. Unsurprisingly, companies have proven reluctant to share data with their rivals. However, the government is determined to merge the individual efforts into a comprehensive credit reporting system. In January of this year, a new company led by the National Internet Finance Association of China (NIFA) submitted an application to People’s Bank of China for a license to operate the country’s first centralized personal credit reporting agency. The application, publicized by the central bank on its website, shows that NIFA will become the leading shareholder, with a 36 percent stake in the new company, while eight credit reporting firms, including Sesame Credit and Tencent Credit, will each hold 8 percent. They are aiming to serve not only traditional commercial banks, but also new Internet-based financial institutions such as online micro-lenders, P2P-lending intermediaries, and online shopping platforms.

Going global?

By any measure, China has become the world leader in the fintech industry. Though largely reliant on China’s relatively closed domestic market, several industry leaders are setting their sights abroad. China’s expanding outbound tourism industry offers an easy entry point for Chinese fintech firms. According to the U.N. World Tourism Organization, 135 million Chinese tourists spent a total of $261 billion abroad in 2016, far outstripping the United States, the world’s second-largest market for outbound tourism. In popular destinations such as Hong Kong, Thailand, Japan, and Korea, WeChat Pay and Alipay are aggressively expanding their reach by forming local partnerships with places frequented by tourists, including airport duty-free shops, scenic spots, shopping malls, and restaurants.

Chinese fintech firms will not be satisfied with only serving Chinese tourists. They are eager to replicate their success in other markets.

But Chinese fintech firms will not be satisfied with only serving Chinese tourists. They are eager to replicate their success in other markets. Alibaba’s approach is simple: Go after populations underserved by existing financial institutions, develop and promote mobile solutions, and collaborate with local partners. Since 2015, Alibaba’s financial affiliate and Alipay’s operator, Ant Financial, has invested in a series of mobile wallet and other fintech startups in India, the Philippines, Thailand, Singapore, and South Korea. Over the next four years, Alibaba expects more than half of its growth in users to come from overseas markets.

Of course, Chinese fintech firms will face new hurdles as they march into developed economies like the United States. For instance, Ant Financial’s yearlong effort to take over MoneyGram, a money transfer company headquartered in Dallas, Texas, was submitted to CFIUS—the authority responsible for reviewing and approving foreign investment in the United States—three times before finally being rejected at the beginning of 2018. This follows a case from last September, when CFIUS rejected a bid by a group that included Tencent and NavInfo, a Beijing-based mapping provider, to buy a 10 percent stake in Here, an Amsterdam-based mapping company with assets in Chicago.

As 2018 unfolds, Chinese fintech firms attempting to enter developed markets will likely experience further setbacks given the current geopolitical climate and rising concerns over personal data being acquired by foreign groups. In the meantime, China’s vast domestic market, along with markets in developing countries, still leave plenty of room for these firms to expand over the coming years.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What’s happening with China’s fintech industry?

February 8, 2018