Two weeks ago, Guatemala’s attorney general and the head of a U.N.-backed international commission jointly asked the legislature there to lift the immunity of President Jimmy Morales after uncovering over $800,000 in hidden and unexplained funds that went to his party’s 2015 campaign. Two days later, Morales deepened the political crisis by declaring the U.N.-appointed commissioner persona non grata and ordering him out of the country. Within hours, the country’s Constitutional Court had provisionally remanded that order, and on Monday it found enough evidence to permit the legislature to consider lifting Morales’ immunity. Some in Congress are also pushing back on helpful judicial reforms.

Now the country is waiting to see how this battle over impunity will be resolved and whether a morally and legally damaged president can survive. The outcome of this contest will shape not only whether Guatemala can emerge from decades in the grip of powerful criminal-political-security networks, but also whether an innovative hybrid international-national experiment will be able to continue to serve as a model for combating corruption and impunity in other countries. It also offers a chance for the Trump administration to take an early visible stance in favor of controlling the crime and corruption in Central America that abet violence, migration, and drug trafficking.

Why Guatemalan elites fear CICIG

The International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) was launched in 2007 to dismantle parallel security groups with links to criminal organizations and political elites that persisted after a 1996 peace agreement ended decades of civil war. Staffed by international experts and vetted Guatemalan prosecutors and investigators, it is empowered to independently investigate cases and jointly bring them to the courts with the national Public Ministry. CICIG used modern investigative techniques and empowered national investigators, reducing the portion of acquittals to condemnations for homicides by half between 2005-06 and 2012-13. Guatemala’s homicide rate fell from 46 per 100,000 in 2008 to 27 in 2016. The United States, seeing CICIG as a contribution to democratic stability in a violent country that is source to migrants, has been a solid backer of the experiment and provided roughly half of its $12-$15 million annual budget. Current U.S. Ambassador to Guatemala Todd Robinson has been outspoken in favor of CICIG’s performance, drawing President Morales’ ire.

The Commission has been the driving force in embezzlement charges against a former president and charges of extrajudicial executions against an ex-minister and the head of police criminal investigations, as well as senior security officials. It has also put dozens of prominent drug traffickers and politicians and security officials behind bars, including the interior minister who helped create it. It has forced the ouster of over a dozen corrupt judges and a tainted attorney general, and sparked the dismissal of over 2,500 police officers. CICIG shocked the country in 2010 by proving that then-President Colóm was innocent in a remarkable suicidal ruse whereby the victim had contracted his own killing in order to blame Colóm and bring him down.

Since 2013, Ivan Velásquez, a Colombian prosecutor known for exposing paramilitary-politician collusion in his country, has headed CICIG. In 2015, CICIG’s investigations of a multi-million-dollar customs fraud ring led to the arrest of some 200 people, including the country’s vice president and its then-president Otto Perez, both of whom resigned. CICIG continued its work with the support of President Morales until the recent imbroglio. Following Morales’ attempt to oust Velásquez, several cabinet and other senior officials left the government. In their resignation letter, the health minister and her vice ministers opined that the president had “assumed a position in favor of impunity and the corrupt sectors of the country.”

What makes CICIG novel

CICIG is significant not just due to its impact at the highest levels in Guatemala, but because so many prior international approaches to combat corrupt regimes have not worked. Decades of traditional development assistance to judicial institutions and to corrupt or abusive police forces have not been able to overcome the entrenched character of corrupt political systems in Latin America. Foreign aid for the “rule of law” has helped reform criminal codes, introduce updated investigative approaches, and confer technologies. However, hundreds of millions of dollars to Latin American justice and police forces have not ended corrupt networks reaching the highest levels of governments. Investigations of the Odebrecht company in Brazil reveal payoffs of some $800 million to officeholders and political candidates in a dozen countries, including $35 million to Peru’s then-president, showing how extensive the problem is.

Even the heavy footprint of U.N. peacekeeping missions has not been able to break corrupt mafias. With thousands of troops and resourced mandates to reconstitute new civilian police and justice institutions, peace operations have left behind post-war societies plagued by violent criminal organizations and corrupt mafias in places such as Bosnia, Kosovo, El Salvador, Afghanistan, Haiti, and Tajikistan. U.N. and NATO peacekeeping missions are structured and mandated principally to enhance security rather than the quality of justice. They can train and mentor police and military forces, but are not generally empowered to strengthen national prosecutions through joint criminal investigations.

This is what has made Guatemala’s CICIG such an interesting experiment. It began as an attempt to dismantle security threats but ended up bolstering the justice system in ways that improved governance. As a U.N. peace operation was winding down in the early 2000s, parallel security groups with ties into the state continued to kill human rights activists and those seeking accountable governance. Human rights groups sought an international commission to help fulfill the government’s pledge to dismantle these groups made in a 1996 peace accord that ended 36 years of civil war. The initial proposal failed in the face of elite opposition and constitutional objections, but eventually the Guatemalan government worked with the U.N. to create CICIG.

CICIG is the first hybrid international-national investigative body to tackle present-day problems of impunity and criminal armed groups. Although it emerged from a peace process, its focus is not on crimes associated with the prior civil war (like Sierra Leone’s hybrid Special Court). It falls short of a U.N.-authorized mission but involves unprecedented powers by internationals to independently select and investigate criminal cases that are then taken jointly with national prosecutors before the Guatemalan courts. It thus overcomes the problems of conventional justice aid programs in which national courts can bury, ignore, or dismiss internationally-assisted criminal investigations. And it offers the advantage of bolstering, rather than supplanting, the capacity and legitimacy of national institutions.

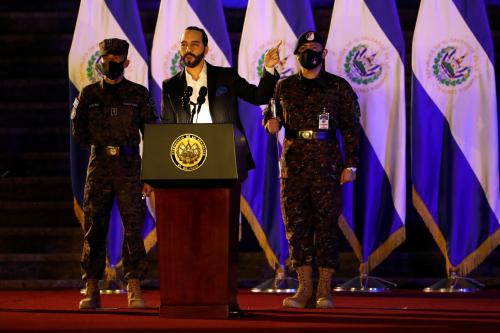

Despite slow initial progress, some premature accusations, and questionable decisions on where to focus efforts, CICIG has become a model in the hemisphere. In April 2016, the Organization of American States opened a Support Mission against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH), whose international investigators and prosecutors can select cases where they assist vetted Honduras prosecutors and investigators to take forward. Discussions about a possible CICIG-like body have percolated in El Salvador and Panama as well, though without success thus far. Next month, the 13-year U.N. peacekeeping operation in Haiti will be replaced by a “U.N. Mission for Justice Support” focused on the rule of law and human rights. In short, CICIG has been at the vanguard of an international shift from concerns exclusively with stability and security in post-war countries to concerns about corrupt governance and everyday criminal justice in such societies.

CICIG has been at the vanguard of an international shift from concerns exclusively with stability and security in post-war countries to concerns about corrupt governance and everyday criminal justice in such societies.

CICIG in the context of global anti-corruption efforts

That is why the current crisis of CICIG poses a threat to the global trend of strengthened action against entrenched corruption. If President Morales is able to push Commissioner Velásquez out of the country, then the selection of the next commissioner will be shaded, and CICIG’s ability to investigate and help bring charges against elites will be indelibly damaged. The cover that CICIG has provided for Guatemalan prosecutors who want to do their jobs despite the risks will be diminished, bolstering the caution and fear among investigators and prosecutors that CICIG had undercut.

Furthermore, in today’s globalized world, the victory of impunity over this novel hybrid institution will undercut the ability of comparable institutions like Honduras’ MACCIH in the future. Civic organizations have mobilized in numerous countries in the last decade, angry that corrupt politicians and criminal organizations have combined to foster insecurity and to gut democratic representation. In countries where independent prosecutors and courts can operate, anti-corruption efforts are making remarkable headway. Corruption charges have recently ousted presidents in South Korea, Brazil, and the Gambia, and put ex-presidents behind bars in Peru, Taiwan, El Salvador, Panama, and Montenegro. It is precisely in countries like Guatemala where corruption and impunity cast the shadow of fear and intimidation on judicial institutions that such headway can benefit from this experiment in what Stanford professor Stephen Krasner calls “shared sovereignty,” where governments invite highly empowered international entities.

The U.S. response to recent developments can tip the scales of justice one way or another. The Trump administration and the U.S. Congress have an opportunity in Guatemala to back the efforts toward accountability in ways that will continue to dismantle criminal enterprises and dissuade corrupt behavior. U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Nikki Haley and members of both parties in Congress have denounced the attempt to oust Velásquez. However, leveraging aid and other (dis)incentives may be needed to prevent a major setback. If Morales is able to decapitate or weaken CICIG, then corrupt politicians and criminal organizations around the hemisphere will take note. The momentum gained by this initial experiment in a constructive international mission against injustice may be dealt a blow that reverberates.

Commentary

What Guatemala’s political crisis means for anti-corruption efforts everywhere

September 7, 2017