The Federal Reserve and the U.S. Treasury Department “have been working at cross purposes” when it comes to their actions on debt management since 2008, according to the authors of

a new working paper

published this week by the

Hutchins Center on Fiscal & Monetary Policy

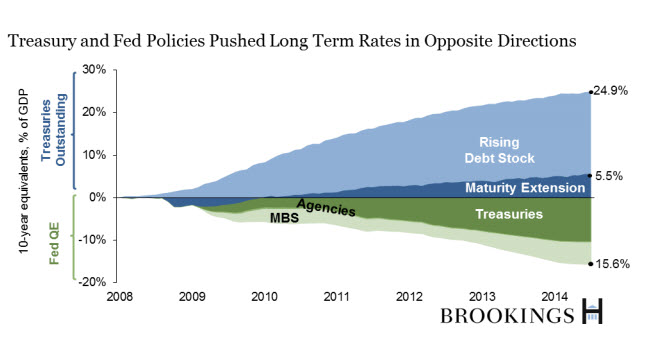

. Robin Greenwood, Samuel Hanson, Joshua Rudolph, and Lawrence Summers review the “extraordinary fiscal and monetary” policies pursued in response to the economic downturn of the Great Recession, finding that Fed and Treasury policies pushed long-term interest rates in opposite directions, in effect partially canceling each other out.

In normal economic times, the Federal Reserve pursues its “dual objective”—to maximize employment and price stability (e.g., keep inflation in check)—via monetary policy tools, including setting the federal funds rate (the rate banks charge each other for short-term loans which then affects interest rates and lending throughout the economy) and controlling the supply of money. As an independent agency, the Fed is free (theoretically) from political influence. On the other hand, the U.S. Treasury conducts fiscal policy, or the taxing and spending activities of the federal government. One of the jobs of the Treasury Department is to manage U.S. debt, and one of its tools is to issue securities to investors to raise the money to finance government operations. Its actions are subject to political oversight through Congress and the presidential administration. Again, in normal times, the two agencies operate independently of each other.

The term “extraordinary” references the fact that in response to the recession, the Fed had pushed interest rates to zero, thus operating at what economists call the “zero lower bound.” Once the Fed had pushed short-term interest rates to zero in 2008, it embarked on a program of buying trillions of dollars in long-term Treasury securities in an attempt to reduce the supply of long-term bonds held by private investors. This “quantitative easing” is an unconventional central bank approach that some have criticized.

At the same time, the U.S. Treasury Department, using its fiscal policy tools to manage the U.S. government’s long-term debt, was selling off long-term securities to help finance the U.S. budget deficit.

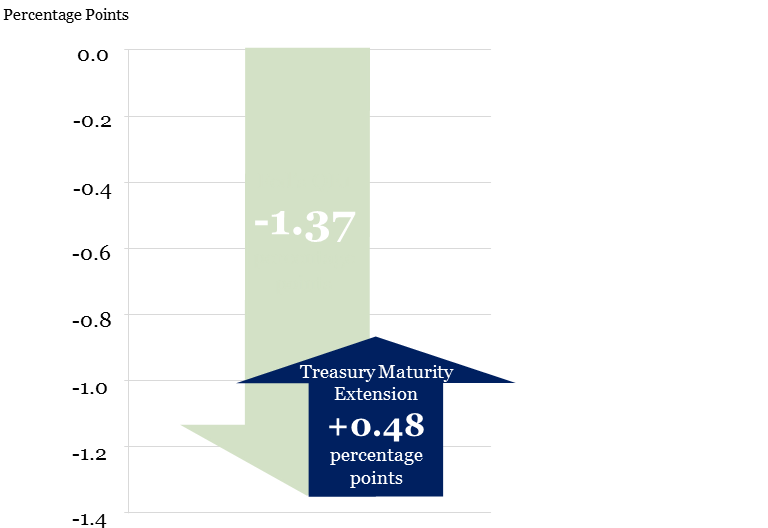

Thus, observe the authors of the working paper, “monetary and fiscal policies have been pushing in opposite directions in recent years” the net result being that about a third of the decline in long-term rates engineered by the Fed’s quantitative easing was undone by Treasury’s policy of selling more long-term bonds.

In order to better manage the federal government’s debt in the future at a time when interest rates fall to zero (again, “extraordinary” times), the authors of the working paper call for more coordination between the two actors. One solution they propose is “for the Fed and the Treasury to annually release a joint statement on the strategy for managing the U.S. government’s consolidated debt. This would establish a plan for the maturity structure and composition of debt issued by the Treasury, and supported by the Federal Reserve.” This “is particularly important,” they write, “when conventional monetary policy becomes constrained by the zero lower bound, leaving debt management as one of the few policy levers to support aggregate demand.”

Read their paper to get the full analysis and recommendations.

At an event yesterday to discuss the paper, Hutchins Center Director David Wessel moderated a conversation among the paper’s authors and representatives of the public and private sectors in response to the paper. During the event, Summers, who served as secretary of the Treasury from 1999-2001 and director of the National Economic Council from 2009-2010, said that “I find the suggestion that the kind of coordination that we’re envisioning threatens central bank independence to be at the edge of absurd.”

At an event yesterday to discuss the paper, Hutchins Center Director David Wessel moderated a conversation among the paper’s authors and representatives of the public and private sectors in response to the paper. During the event, Summers, who served as secretary of the Treasury from 1999-2001 and director of the National Economic Council from 2009-2010, said that “I find the suggestion that the kind of coordination that we’re envisioning threatens central bank independence to be at the edge of absurd.”

Jerome Powell, a Federal Reserve Board governor and one of the respondents to the paper, posed some critical questions, including: “What will happen when … a Treasury Department strongly disagrees with what the Fed is doing? What will happen to expectations in the marketplace, for example, about the debt ceiling when there is such cooperation? There is a conundrum at the heart of this.”

Get full event audio and video here, an event summary here, and select event coverage from The New York Times and Wall Street Journal.

Learn more about the effect of the Treasury Department’s debt management policies on the Fed’s quantitative easing program in this series of charts that shows how Treasury’s decision to sell more long-term bonds undid about a third of the impact on 10-year Treasury yields brought about by quantitative easing.

Learn more about the effect of the Treasury Department’s debt management policies on the Fed’s quantitative easing program in this series of charts that shows how Treasury’s decision to sell more long-term bonds undid about a third of the impact on 10-year Treasury yields brought about by quantitative easing.

Commentary

Were the Federal Reserve and U.S. Treasury Working at Cross Purposes in Response to the Great Recession?

October 1, 2014