The inequitable distribution of teachers is among the largest and most pervasive challenges facing American schools. A host of studies has shown that stronger teachers—as measured by experience, credentials, education, teaching practices, and student growth—are more likely to be found working with students who are affluent and white. We have found these distributional asymmetries across districts, among schools in the same district, and even within schools.

As illustrated in other posts on the Brown Center Chalkboard, these distributional maladies are also present when we consider characteristics beyond instructional efficacy, such as teacher race. Black and Hispanic teachers are in short supply and are often clustered within a small proportion of schools and districts. Being taught by a diverse group of teachers benefits all students, with the greatest returns manifesting for low-income and Minoritized students.[1] Such benefits extend beyond human capital when we consider the democratic aims of education, where exposure to diverse and wide-ranging ideas, people, and experiences provide the foundation for students to develop the skills of civic discourse. A diverse faculty plays a critical role in supporting multiple goals central to our educational system.

Representative bureaucracy and the distribution of teacher race

Given the established benefits to having a diverse teacher workforce distributed equitably across schools and students, what is causing teachers—particularly Minoritized teachers—to be distributed as they are? A better understanding of the underlying mechanism allows us to select the optimal policy levers to disrupt these trends.

In our newly released paper examining this question, Minseok Yang, Yasmin Rodriguez-Escutia, and I constructed a dataset comprised of more than 70,000 applications (more than 12,000 unique teachers) to about 2,000 teaching vacancies across 352 (of 425) districts in Wisconsin. We used this to gain an unprecedented glimpse into the teacher sorting process that occurs as teachers apply to and move among schools.

We motivated our study by incorporating the theory of representative bureaucracy (based off of Samuel Krislov’s book of the same name), which hypothesizes that people are more likely to work in organizations led and managed by people with whom they may have shared similar life experiences. In schools, this manifests as Minoritized teachers being more likely to work in schools where they see other Minoritized educators in leadership positions. The logic is that Minoritized teachers face unique social and professional pressures; schools with Minoritized leaders are likely to understand these pressures and can provide a teaching environment in which Minoritized teachers can feel safe, supported, and prepared to excel.

Racial matching and job seeking

In our analyses, we sought to determine how teacher-principal race congruence relates to how likely a teacher may be to (a) search for other positions and (b) leave their current school. We next explored if teachers were any more likely to apply to vacancies in schools led by a principal with whom they shared the same race. Lastly, we asked if teacher-principal race congruence was predictive of hiring, conditional on those teachers who applied to the vacancy.

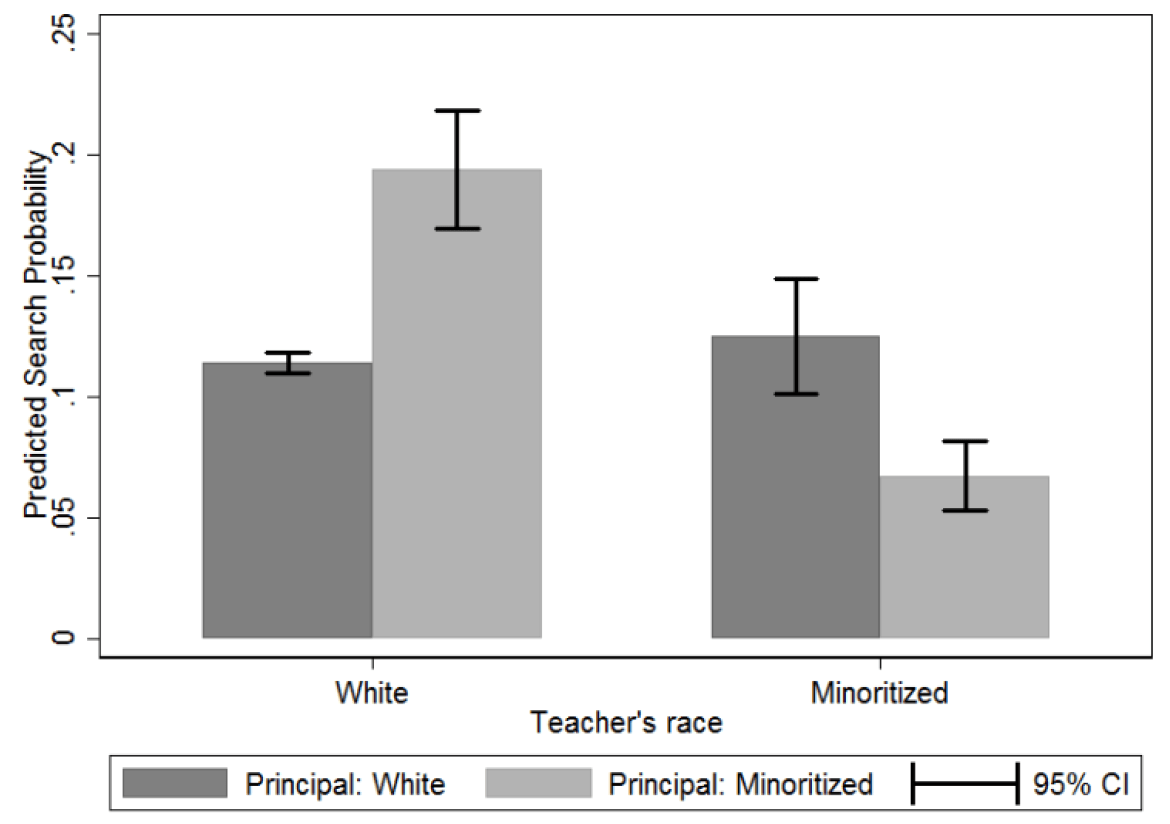

Overall, we found compelling evidence that teacher-principal race congruence is a significant factor that moderates how teachers select the schools in which they work. As shown in the figure below, teachers working with a different-race principal are twice as likely to search for other positions. While teacher-principal race matching reduces search rates among all teachers, this racial congruence effect is most pronounced for pairings of Minoritized teachers and Minoritized principals. And this effect holds even after controlling for multiple teacher characteristics and school factors, including student demographics.

Figure: Marginal probabilities (effects) of searching in the labor market based on principal-teacher race congruence

We also found that teachers were more likely to apply to vacancies where they are of the same race as their potential principal. Here too, the effects are greater for congruence among minority educators than for their white colleagues. Importantly, we found no evidence to support that Minoritized principals are any more or less likely to hire Minoritized teachers than are their white colleagues.

Diverse leadership can help diversify more schools

Our findings provide the strongest empirical evidence to date that the sorting of Minoritized teachers among schools is strongly related to the race of the principal leading the school. This leads us to believe that one strategy to diversify our teaching workforce across more schools is to increase the recruitment and/or promotion of Minoritized school leaders. If representative bureaucracy is underlying Minoritized teachers’ propensity to seek schools led by Minoritized principals, we should also consider how white principals can signal that they are aware of the challenges facing Minoritized teachers, and their school will provide a responsive and prosperous professional culture.

While our work informs strategies to remediate the maldistribution of Minoritized teachers, we cannot ignore that we face a severe shortage of Minoritized teachers. In Wisconsin, for example, 21 percent of all students are black or Hispanic as compared to less than 4 percent of all teachers. 74 percent (!) of Wisconsin schools employ zero teachers of color. Statewide, Minoritized teachers are too few and segregated across districts. This level of segregation merits our attention, yet policies to improve the distribution of Minoritized teachers may produce the unintended consequence of inducing a sense of racial or ethnic isolation. Extreme distributional balance in Wisconsin would result in only one Minoritized teacher per school. Such an event may well accelerate attrition from the field. When considering initiatives to diversify our teachers and principals, we also need to be proactive in our efforts to increase the numbers of Minoritized individuals entering teacher education programs and matriculating into the teaching workforce. Supply challenges are inextricably linked to distributional ones and strategies to address one must be cognizant of the potential impact on the other if we want to move the dial on these critical issues.

The racial diversity of teachers matters to policymakers, and our work shows that the race of principals has a clear impact on teachers’ labor market decisions as well. If we want to create schools that welcome all of our increasingly diverse students, we need to think about racial diversity for school leaders in addition to teachers.

Footnote

[1] Both in our paper and in this article, our use of the term “Minoritized” rather than racial or ethnic minority is intentional. The term “minority” is a neutral term on its face, describing the relative sizes of nonwhite racial and ethnic groups relative to the majority (i.e., whites). Yet, this term is inadequate because it fails to convey that these nonwhite groups have poorer social outcomes not simply because of their size relative to whites, but because they have often been marginalized and mistreated in society. We feel “Minoritized” more accurately conveys the notion that their lower social status is the result of historical oppression. (Back to top)

Commentary

Want more diverse teachers in more places? Start with diverse principals

December 14, 2018