As Election Day approaches, many city leaders across the United States are wondering what a second presidential term for Donald Trump might mean for their residents and communities. Over the past several months, they have watched as Trump described Milwaukee as “horrible,” New York as a “city in decline,” and Philadelphia as “ravaged by bloodshed and crime.” Trump recently warned (at the Detroit Economic Club, of all places) that “the whole country will be like Detroit” if Vice President Kamala Harris wins the election, and that “you’re going to have a mess on your hands.” City leaders recall conflicts with the previous Trump administration over issues such as administering the decennial census, ensuring public safety, and providing adequate funding.

Immigration policy, however, should top their concerns. Candidate Trump signaled numerous ways in which he and his cabinet would seek to reduce the presence and impact of immigrants of nearly all kinds in American life. Recent Brookings analysis quantified the potential national economic impact of this agenda. And as the analysis below shows, these proposed policies would be especially harmful to cities, which have long relied upon immigration for critical demographic, economic, and cultural fuel.

The GOP wants fewer immigrants—of almost all kinds—in the United States

While Trump and running mate JD Vance’s recent spotlight on Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio grabbed headlines, the GOP’s agenda on immigration reaches much more broadly. Based on Trump’s speeches, statements from campaign officials, and Project 2025’s “Mandate for Leadership,” this agenda includes:

- Rounding up, detaining, and deporting an estimated 11 million unauthorized migrants

- Further restricting the entry of refugees and asylum seekers

- Repealing the diversity immigrant visa, which offers pathways to permanent U.S. residency for migrants from countries with historically low numbers of immigrants

- Limiting family-based admissions of immigrants (to nuclear family members only)

- Scaling back the use of H-1B (high-skilled immigrant) and H-2B (seasonal immigrant worker) visas

- Repealing temporary protected status (TPS) for immigrants fleeing unsafe situations in their home countries (including 450,000 recent arrivals from Venezuela)

- Ending Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival (DACA) protections for minor children whose parents brought them to the U.S. illegally

- Reinstituting the “Muslim ban,” effectively barring the entry of individuals from a range of Muslim-majority countries

Such policies would reflect Trump’s warning that immigrants are “poisoning the blood” of America, and fulfill promises from policy adviser Stephen Miller that a second Trump presidency “will unleash the vast arsenal of federal powers to implement the most spectacular migration crackdown.” As was true in the previous Trump administration, many (if not all) of these policies would face legal challenges, funding challenges, or both. But such a multipronged policy assault on immigration—likely coupled with continued anti-immigration rhetoric—would undoubtedly have both direct and indirect effects on immigrants’ presence and contributions to America’s economy and society.

Examining the potential local impacts of an immigration crackdown

While it is not possible to know what each of the GOP’s myriad proposals would mean for specific places and their populations, their broad reach suggests that they would have overall disproportionate impacts on communities where immigrants tend to live and work, especially America’s cities and urban areas.

To assess these potential impacts, this analysis uses a Brookings Metro methodology to examine the distribution of the nation’s more than 45 million foreign-born individuals (immigrants) across six community types, highlighting the unique relationship between immigration and major urban communities. It identifies four community types in major metropolitan areas (the 111 metro areas with at least 500,000 residents in 2023):

- Major cities (148 total) include the largest city in each major metro area, plus all other cities in those metro areas that had at least 100,000 residents in 2023.

Other counties in major metro areas are defined as net of their major city populations:

- Urban counties (98 total) have at least 95% of their residents living in an urban area—communities that the Census Bureau identifies as having high population density. Examples: Cook, Ill. (containing Chicago); Gwinnett, Ga. (outside Atlanta).

- Inner suburban counties (175 total) have between 75% and 95% of their residents living in an urban area. Examples: Multnomah, Ore. (containing Portland); Lorain, Ohio (outside Cleveland).

- Outer suburban counties (336 total) have fewer than 75% of their residents living in an urban area. Examples: Westmoreland, Pa. (outside Pittsburgh); Plaquemines Parish, La. (outside New Orleans).

Two additional county types account for the remainder of the U.S. map:

- Small metro counties (560 total) are part of metropolitan areas with fewer than 500,000 residents. Examples: Mercer, N.J. (Trenton metro area); Washington, Utah (St. George metro area).

- Nonmetro counties (1,951 total) are located outside metropolitan areas (including in micropolitan areas), and range in size from Loving, Texas (64 residents in 2020) to Sussex, Del. (237,378 residents in 2020).

Immigrants comprise a significant share of population in US cities and urban counties

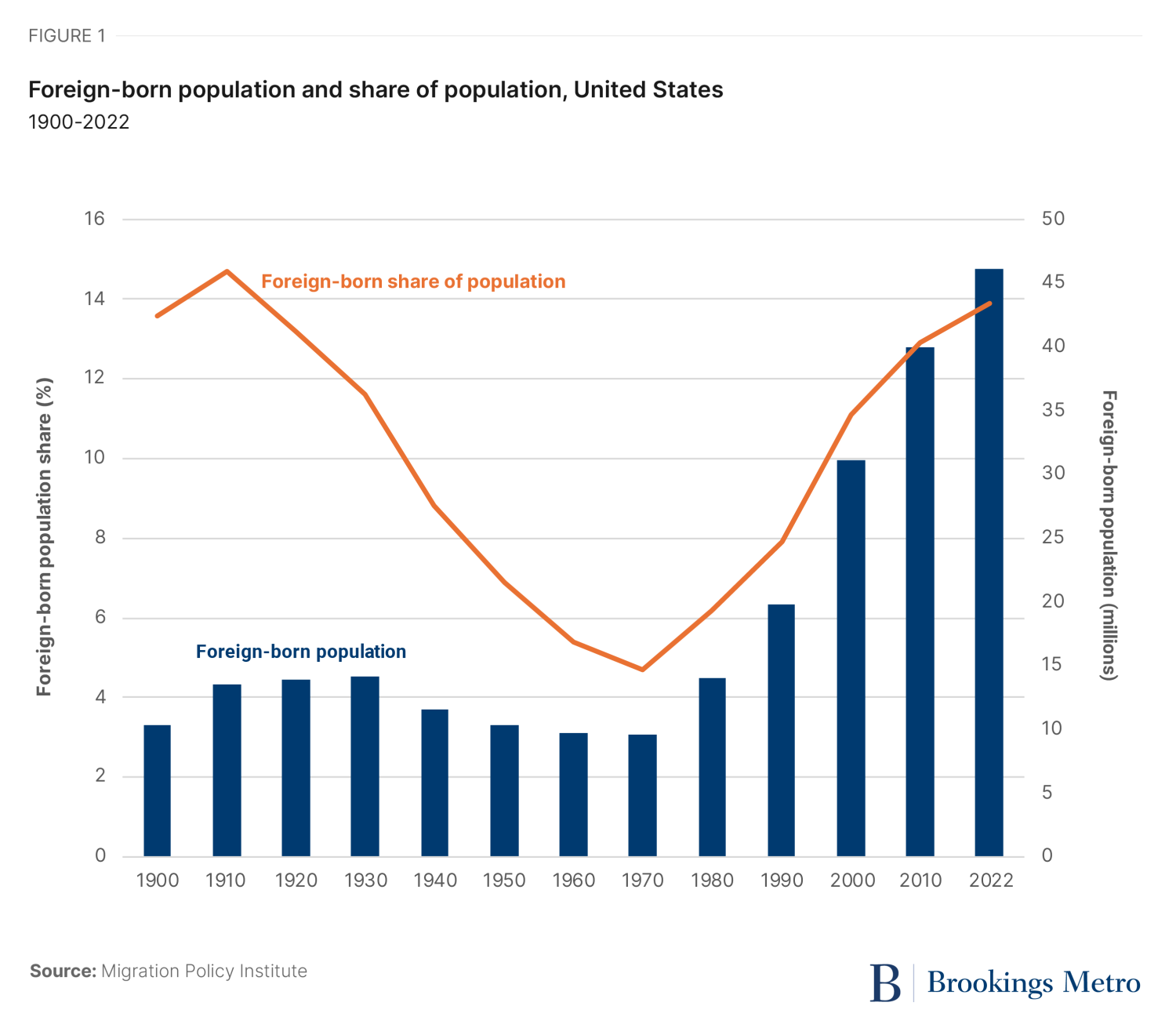

The share of the U.S. population born abroad has been rising for the better part of the last five decades, since the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act in 1965. Today, nearly one in seven U.S. residents was born abroad, up from fewer than one in 20 residents in 1970, and the foreign-born share of U.S. population is approaching that from the turn of the 20th century (Figure 1).

Immigrants comprise an even larger share of the population in major U.S. urban areas. From 2018 to 2022, the latest period for which complete data is available, foreign-born individuals accounted for 21% of residents in major U.S. cities, and 22% in urban counties. Immigrants’ share of population was smaller but still significant (12%) in inner suburban counties, followed by small metro areas, outer suburban counties, and nonmetro counties (Figure 2). Overall, major cities and urban counties contained 42% of all U.S. residents, and 67% of foreign-born U.S. residents.

The major cities and urban counties with the highest shares of foreign-born residents anchor some of the most economically diverse and dynamic metropolitan areas in the country (Table 1). These jurisdictions, where at least one in three residents was born abroad, lie in and around New York, the San Francisco Bay Area, Miami, Boston, Seattle, and Washington, D.C.

Immigrants account for a disproportionate share of recent growth in US cities and outside metro areas

As my Brookings colleague William H. Frey has written, immigration has recently fueled U.S. growth, especially in the wake of the pandemic. He finds that over the past three years, immigration contributed more to U.S. population growth than natural increase (the excess of births over deaths)—a reversal of historical patterns.

Immigration has made especially critical contributions to population stability and growth in U.S. urban areas over the past two decades. Between 2000 and 2018-22, increases in foreign-born residents accounted for 31% of overall growth in major city populations, and 44% of overall growth in urban county populations (Figure 3). And while immigrants still comprise a relatively small share of the population in nonmetro counties (4%), they accounted for nearly half of aggregate population growth in those counties during this period.

At the local level, immigration often accounted for population growth or stemmed further decline due to domestic out-migration or natural population decrease. There were 10 major cities and 16 urban counties that grew over the past two decades, but that would have lost population without increases in foreign-born residents. For instance, Tulsa, Okla. would have lost roughly 1,500 residents between 2000 and 2018-22 in the absence of increased immigration; instead, it gained nearly 19,000 residents. Newark, N.J. would have lost 6,800 people without immigration; instead, it gained 33,800 because of it. Similarly, 17 major cities and eight urban counties lost population, but immigration softened the demographic blow. Jefferson Parish, just outside New Orleans, lost a little more than 19,000 residents over the two decades, but would have lost more than double that (roughly 42,000) had it not been for the increase in its foreign-born population (see Appendix).

While smaller in magnitude, immigration also made significant impacts on the demographic trajectory of many small town/rural counties outside metropolitan areas. A majority (59%) of these counties lost population between 2000 and 2018-22. In 795 of those 1,155 counties, however, the immigrant population rose, mitigating further demographic decline. Similarly, 68 nonmetro counties avoided population loss due to the demographic contributions of immigrants, from large counties such as Monroe, Fla. (+2,455 residents overall, +4,434 foreign-born residents) to small counties such as Hemphill, Texas (+20 residents overall, +321 foreign-born residents).

Over the past two decades, the presence of immigrants has risen in all types of U.S. communities. This is especially true in urban and inner suburban counties, where the foreign-born share of the population rose by 4 percentage points between 2000 and 2018-2022 (Figure 4).

Immigrants form a critical, diverse part of urban America’s skills base

The education and skills of individuals—what economists call “human capital”—is the single largest contributor to the long-term growth of places. In addition to supporting the demographic vitality of major urban areas, immigrants supply a large and diverse range of human capital to fuel urban prosperity.

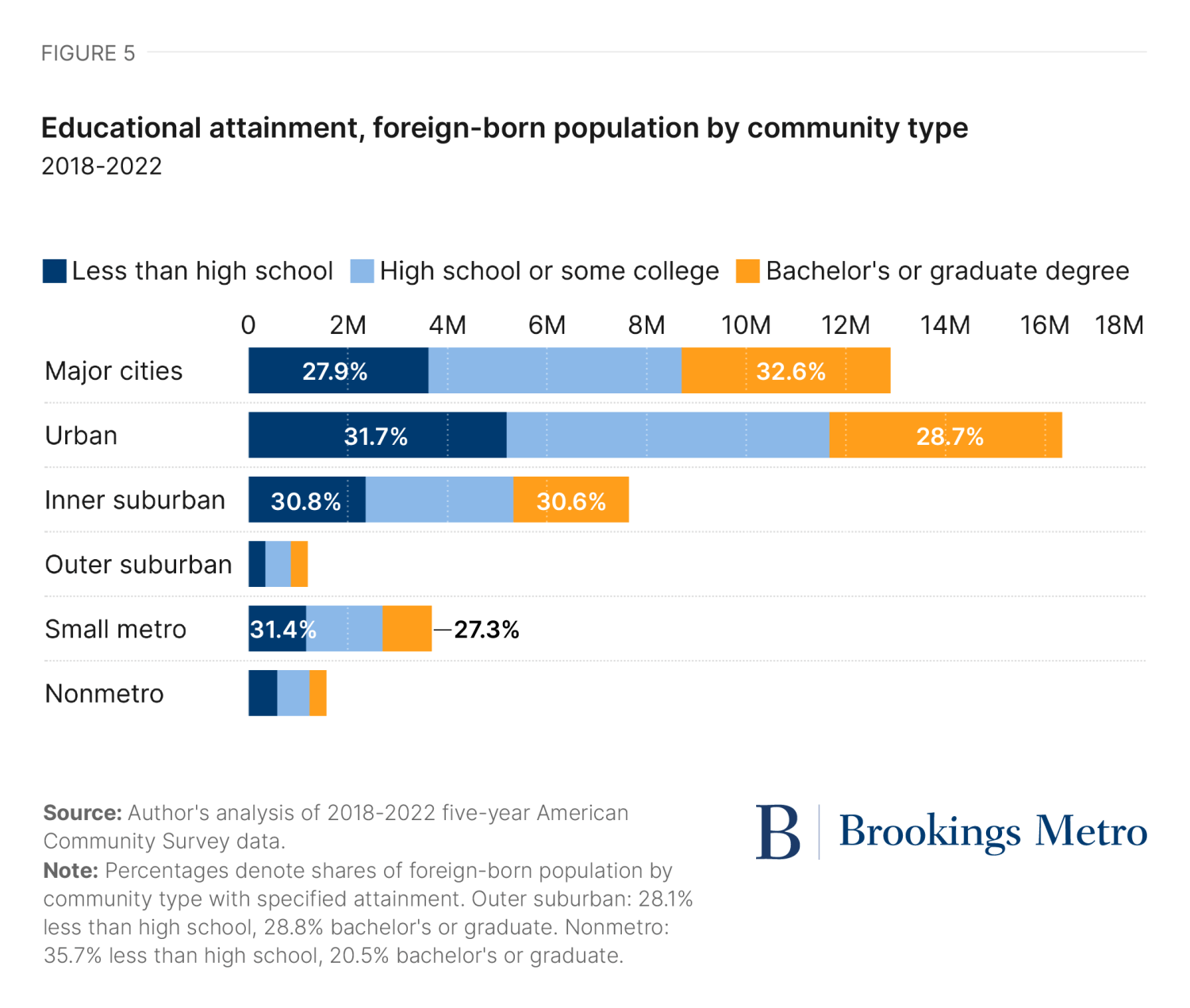

Nationwide, just under 30% of foreign-born adults in the United States in 2018-22 held a bachelor’s or graduate degree. That share was higher in major cities (33%) than in other community types (Figure 5). And because immigrants also make up a large share of the overall population in major cities, they comprise nearly one-quarter (23%) of all college degree holders living in those places, contributing their expertise in key sectors such as health care, higher education, and professional/scientific services. For instance, in San Diego, one of the nation’s leading centers of scientific and technological research, 37% of foreign-born residents hold a bachelor’s or graduate degree, and they comprise 27% of all San Diegans with those credentials.

Many immigrants, of course, come to the United States with more limited formal education. In 2018-22, about 30% of foreign-born U.S. adults did not complete high school. This rate was similar in major cities (28%), where many of these immigrants also make up critical segments of the workforce in industries such as construction, hospitality, and personal services. In short, it is difficult to imagine the successful functioning of major urban labor markets in the absence of immigrant workers of all kinds.

Immigration policy is urban policy, and the GOP’s urban policy threatens city well-being

As the 2024 presidential campaign enters the home stretch, former President Trump’s top pitch to voters is that by reducing the presence and growth of immigrants of all kinds, he will protect the interests of native-born workers and communities. There are many demographic, economic, cultural, and humanitarian reasons, rooted in U.S. history, to be concerned about this assertion at face value.

This analysis sounds a somewhat more targeted, but no less urgent, call: If the leaders of America’s major cities and counties hope to preserve and expand the vitality of their places, they should have grave concerns about the anti-immigration, anti-immigrant agenda that Trump promises to carry out if he prevails in November. Ohio Governor and Springfield native Mike DeWine recently expressed those concerns in response to Trump and Vance’s false comments about his hometown. His example demonstrates how local leaders nationwide have an important platform from which to remind the public about the tremendous value of immigration to local economies and communities, and what their places stand to lose if a majority of voters endorse the GOP’s immigration policy agenda in November.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).