Budgeting rules of thumb will tell you to follow the 50-30-20 guideline. Once you have calculated your after-tax income, you should allocate 50 percent to necessities, such as transportation and housing, 30 percent to “wants,” which include anything from phone bills to vacations, and 20 percent to savings for the future and repaying any debts. But the unfortunate truth is that for many Americans these guidelines simply aren’t realistic. Housing prices have risen, and while innovations may have made food and clothing more affordable, they’ve also contributed to the ever-rising cost of health care. As a result, low-income households are under increasing pressure to make ends meet, not to mention invest in their future economic security.

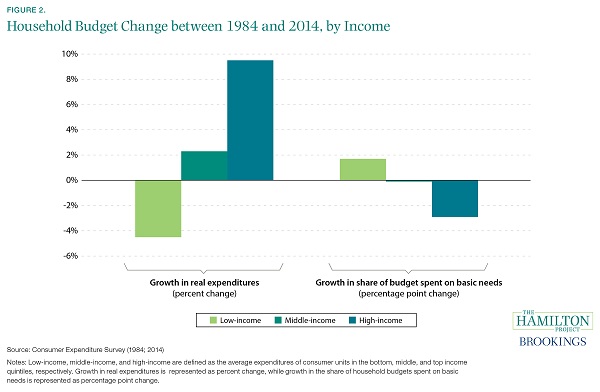

Over the last 30 years, low-income households have had to stretch shrinking budgets to cover their basic needs, as detailed in a recent Hamilton Project analysis. After adjusting for inflation, middle- and high-income households spent more overall in 2014 than they did in 1984, while low-income households spent less. In fact, their budgets shrank by more than four percent—from about $24,800 to $23,700, not an insignificant amount for low-income households. At the same time, low-income households increased the share of their spending devoted to basic needs—defined here as housing, health care, food, transportation and clothing—by almost two percentage points. Meanwhile the share of spending on basic needs declined slightly for middle-income households and fell by about three percentage points for high-income households. Once basic needs are accounted for, low-income households have little money available to save for retirement, pay off debts, or invest in their education and other forms of human capital.

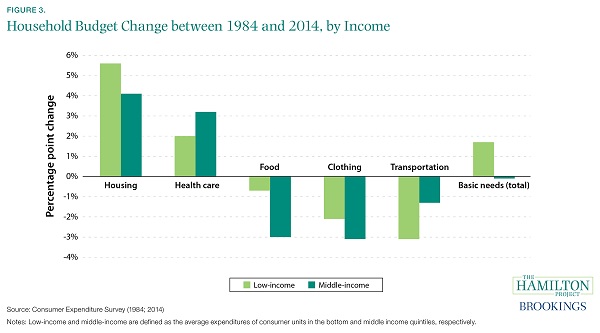

In some instances, increased spending on basic needs has been associated with rising prices that are outside the control of individual consumers. Health care is one example, with both low- and middle-income households increasing their shares of spending on health care as prices rise much more quickly than for other goods and services. Expenditures on health care have increased dramatically from relatively low levels in 1984, though food, transportation, and housing remain more important in household budgets.

Because most of the low-income household budget is devoted to basic needs, households can face serious dilemmas about how to best spend their money. Often, the pressures of a basic needs budget force households to make tradeoffs with serious consequences for their health and well-being:

- a survey of food-insecure food bank clients found that two-thirds of these households report having to choose between buying food and paying for health care;

- adults in low-income households tend to decrease food consumption to offset rising utilities expenditures during the winter;

- an increase in out-of-pocket medical costs for a family was associated with delaying or skipping medical and dental care and prescription drug purchasing for children.

With limited savings and a large share of their budgets devoted to basic needs, low-income households are less able to sustain increased spending on any one category (e.g., unexpected health expenses) while maintaining expenditures on other basic needs.

Social safety net programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), help households afford basic needs during times of economic hardship must themselves keep pace with changing consumption norms and budget pressures. In the case of SNAP, the largest federal nutrition assistance program, benefits are calculated based on food consumption patterns that no longer hold in the modern economy; the Hamilton Project recently released a proposal to modernize this aspect of the program. As the economic environment changes, policy should continue to support broad-based economic progress and security.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Under Pressure: Shifts in Household Spending Over the Past 30 Years

June 3, 2016