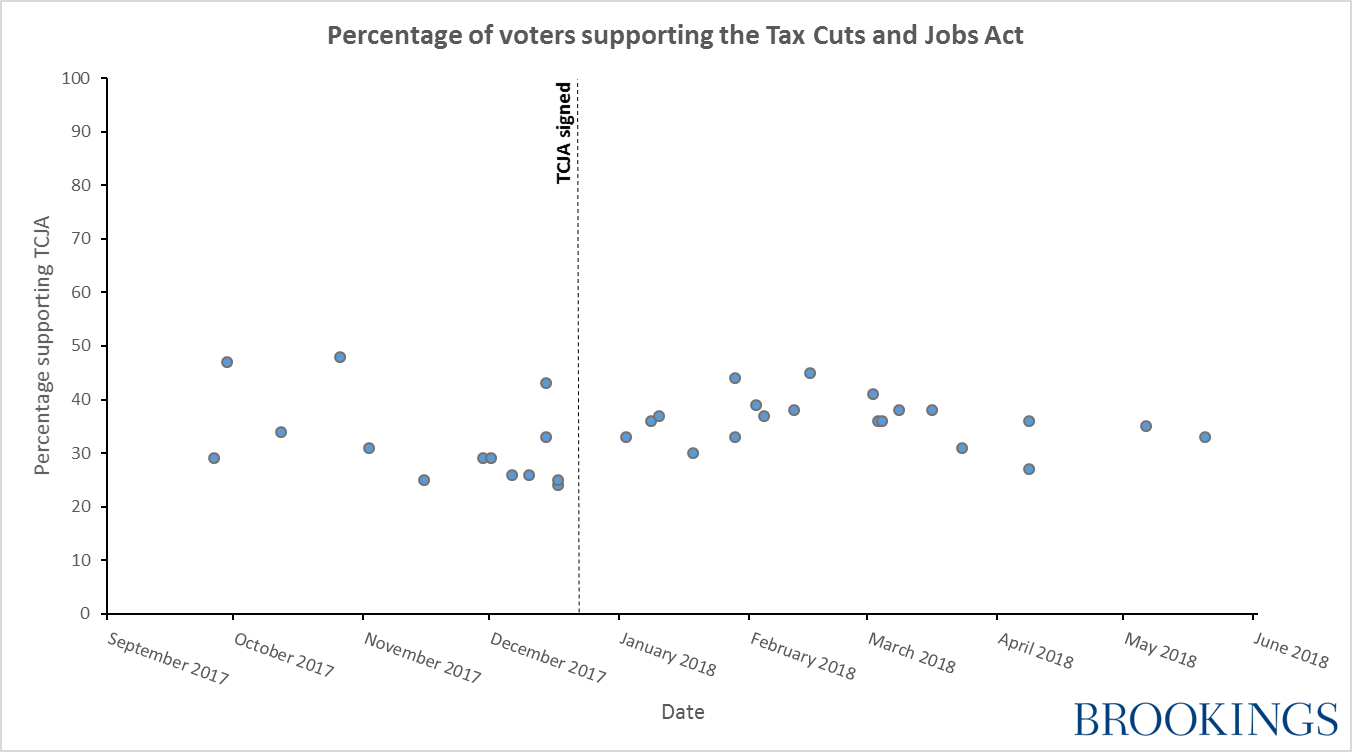

On Dec. 22, 2017, President Trump signed into law the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” or TCJA. The TCJA is the major legislative achievement of the Republican majority during the 115th Congress. The law’s main provisions include a large corporate rate cut, an array of individual tax cuts and increases, and a number of complex provisions that encourage abuse. The TCJA is regressive in its effects, benefiting the wealthy far more than the middle class and the poor—but the legislation frontloads some temporary tax cuts that will slightly boost many Americans’ take-home pay in the short-term. The legislation was remarkable for its unpopularity; approximately 32 percent of Americans supported the legislation in the lead-up to its passage, a level of approval lower than that received by a number of major federal tax increases in years past.

What role will the TCJA play in the 2018 midterms? Political science has a great deal to say about how voters interpret and respond to public policy. Combining this literature with recent public opinion data on the bill provides a useful framework for predicting the legislation’s electoral impact.

This paper follows the following structure. First, I examine how economic conditions have historically shaped electoral outcomes in the United States, and apply that research to the case of the TCJA. Second, I discuss how partisanship interacts with public attitudes about policy, and assess the likelihood that public perceptions of the TCJA will influence voting. Finally, I report what we know about the role of money in politics, and how the TCJA might change the money available to different political interests both in the near and long term.

I conclude that there are only a few avenues by which the legislation is likely to help Republican chances. It is deeply implausible that voters will behave differently due to the very small changes the TCJA made in their individual take-home pay. The legislation is also poorly situated to mobilize Republican voters, whose support for the legislation was lukewarm. The short-term stimulative effects of the TCJA are also unlikely to matter much, both because the effects are small and because the economy matters less for midterm election results. In the longer term, however, Republicans will likely benefit from the law’s upward redistribution targeted to their donor class.

It is deeply implausible that voters will behave differently due to the very small changes the TCJA made in their individual take-home pay.

The legislation also has implications for Democrats. Given public attitudes about the bill, Democrats could treat the TCJA as a major campaign issue, using the Republican mobilization in opposition to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) as a model. In 2010, the Republican campaign against the ACA contributed substantially to the defeat of House Democrats in competitive seats, several scholarly analyses demonstrate. But for Democrats to mirror those results in the 2018 midterm, the party would need to invest heavily in a concerted anti-TCJA campaign, and there is little to suggest that the TCJA will features so prominently in Democratic plans for the fall.

Economic conditions and voting

Voters typically reward incumbent parties for good economic conditions, so if the TCJA were to create such conditions, the law would indirectly provide Republicans with electoral gain. In principle, individual taxpayers might reward the incumbent party for additional money in their own paychecks or for general economic growth. The first of these two scenarios is unlikely, since voters tend to respond to general economic conditions rather than their own personal economic situation. Moreover, voters rarely notice or recall personal benefits they have received through the tax code, and the TCJA’s advantages for most families are not very substantial. The second possibility—electoral gain via general economic growth—is more plausible in principle, but the strong relationship between economic growth and electoral rewards for incumbents only holds in presidential election years.

Individual voters are highly unlikely to reward Republicans for the income increase they personally saw from the TCJA, firstly because the tax cuts most people will receive are small. For people in the bottom three income quintiles, the TCJA will result in an approximately 1 percent increase in after-tax income. Voters in the middle income quintile—those households making between $48,600 and $86,100 annually—will take home a little less than $20 extra each week, on average.1 For many families, this will not be an especially noticeable change in their take home pay, particularly for non-salaried earners, whose incomes vary with their hours.

With the benefit of time and additional polling data, however, there does not appear to be a meaningful increase in public support for the TCJA.

Moreover, voters have historically forgotten much larger and more popular middle-class tax cuts. When President Bush cut taxes across the board in 2003, the following year only one in five Americans remembered benefiting. A year after the tax cuts passed under President Obama, less than one in ten Americans recalled their taxes going down. These instances are in keeping with a broader body of political science research demonstrating that public policy conducted through the tax code is less obvious to voters than direct spending policies. Spending through the tax code has been described by scholars as the “hidden welfare state.”

In the first weeks after the TCJA’s passage, it seemed that the political science consensus was worthy of re-examination. As withholding changed in the new year, some early polling suggested a swing of public support in favor of the legislation. With the benefit of time and additional polling data, however, there does not appear to be a meaningful increase in public support for the TCJA.

Finally, the changes in take-home pay resulting from the TCJA are unlikely to change voters’ behavior because voters typically do not vote based on their own pocketbooks. Instead, the voting public is “sociotropic” in their economic assessments—responding to the ups and downs of the economy as a whole rather than changes in their own individual wellbeing.

Voters are also remarkably short-term in their economic thinking—they tend to reward presidents for good economic times in the period immediately prior to the election. The TCJA will likely have some small stimulative effect in 2018; the Tax Policy Center has estimated that the law will increase US GDP by 0.8 percent in 2018, while the Congressional Budget Office estimated a 0.3 percent boost in 2018 GDP.

How much will that improve Republicans’ electoral chances? Not a lot. In presidential elections, the state of the economy is a good-but-not-perfect predictor of the incumbent party’s re-election chances. But in midterm elections, there is “no relationship between the nation’s growth rate and Senate (or House) seat loss.”2So even if the TCJA gives the economy a short-term jolt, Republicans running for re-election should not expect to benefit from it.

The state of the economy is not the only factor that drives electoral outcomes, however. Taxation is a highly controversial topic, one of the definitive dividing lines between the two major political parties. To understand how the TCJA will matter for the November 2018 election, we have to consider how political partisans perceived the legislation, and whether those perceptions are likely to change voting behavior.

How partisanship shapes Americans’ evaluations of policy

As a rule, partisanship guides voters’ policy assessments. The role of partisanship is likely to be especially strong in attitudes about the TCJA both because it is a piece of legislation strongly identified with a single party, and because the bill passed in a highly polarized context, where most voters are strongly committed to their party and a very small percentage of voters are politically engaged independents.

Attitudes about specific policies do not typically precede voters’ partisan choices. For most voters, partisanship is a social identification that develops in early adulthood and is relatively stable over a lifetime.3 This consistent partisan commitment serves as a lens through which voters assess policy—both focusing attention on information that reinforces partisanship and filtering out information that might conflict with one’s partisan commitment.

Voters typically judge the merits of particular proposals using cues from trusted political elites, who tend to be copartisans. The process by which voters learn and adopt their party’s positions is easiest to see when a new issue rises to national attention. For example, during the first debate between George W. Bush and Al Gore in the 2000 presidential election, the candidates engaged in a heated exchange about whether Social Security funds should be invested in the stock market. The debate brought media attention to a previously second-tier political issue, and both candidates then ran ads about their proposals. Repeated surveys of the same voters revealed that those who supported Bush before the first debate adopted their candidate’s position, favoring putting Social Security funds in the market. Those who identified themselves as Gore supporters came to oppose market investment of Social Security funds. As partisans heard more about the issue from their preferred candidate, they updated their policy opinions accordingly.

In the case of the TCJA, leaders in each party were providing a very consistent message. For voters, the partisan message was loud and clear.

The impact of partisanship on policy assessment is not limited to less educated or less engaged voters; on the contrary, those who follow politics closely are especially likely to adopt the party line because they are more likely to know the party line. Scholars have also demonstrated similar patterns of partisan opinion change over a wide array of topics, including on issues as prominent as the Vietnam War. Voters, especially politically engaged voters, rely on party leaders to interpret policy proposals both big and small.

In the case of the TCJA, leaders in each party were providing a very consistent message. In the House and the Senate, the bill received no Democratic support. Among Republicans, support was nearly lockstep; only 12 Republican House members voted “no” on the final version. Some Senate Republicans, notably Marco Rubio, expressed reservations about the legislation both before and after passage. But these voices were few, and, in the end, every Republican Senator voted for the TCJA. For voters, the partisan message was loud and clear.

Moreover, voters need not have paid close attention to the TCJA debate to recognize the partisan cues, because the partisan split on the tax bill was nothing new. Progressive taxation has been a dividing line between the parties for many decades. Dating back to the late 1970s, Republican leaders have seen tax cuts as a winning political issue and a central component of the party platform. Democrats have been less consistent in their messaging on taxes, but leaders have regularly supported tax increases for very high earners. Voters who follow politics even casually would find the narratives of the TCJA familiar, reinforcing existing partisan attitudes about tax policy.

The role of partisanship in policy evaluation is likely to be especially strong in today’s highly polarized political context. Distrust of the opposite party is especially high, and as media has become more partisan, voters may be less likely to learn the other party’s view on a piece of legislation. There is even less reason than usual to expect voters to consider or even to hear the policy perspective of the opposing party.

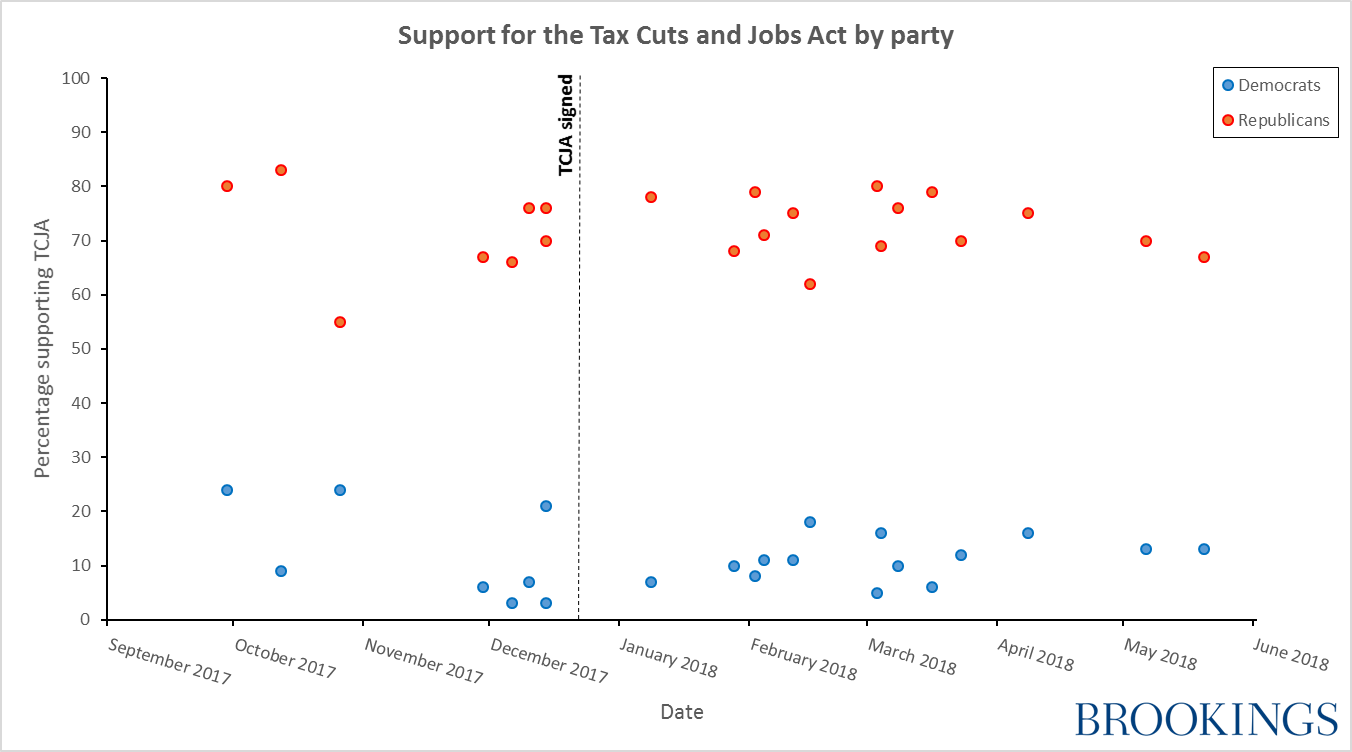

Given how voters assess public policy, we would expect to find the partisan divide among lawmakers recapitulated in public attitudes. And looking at the survey data,4 this is what we find: an enormous partisan gap in attitudes toward the tax bill. On average, 10 percent of Democrats supported the tax bill, while 72 percent of Republicans did.5 The partisan divide persists after the bill’s passage. In short, there is little reason to expect this legislation to shift voters from their partisan camps.

But what about voters without an avowed partisan camp—the moderates, the independents, and the swing voters? Political journalism tends to overestimate the number and electoral significance of nonpartisans.

Self-described independent voters are not the moderate, persuadable, election-deciding voting bloc they are often portrayed to be. Most independents report they “lean” toward one party or the other, and these “leaners” display voting behavior that is largely indistinguishable from people who describe themselves as Democrats or Republicans. As a group, self-described independents are not especially moderate, nor are they especially open to persuasion. Even the 10 percent of the public that claims not to lean to one party or the other has become “as reliable in their party support as strong partisans of prior eras.” The frequency of “swing voting”—that is, voting for one party and then the other in consecutive elections—has collapsed. What is different about “independents” is not their partisan loyalty, but their likelihood of voting. True independents are not reliable voters; they vote about half as often as partisans do.

About 9 percent of Obama voters supported Trump in 2016. Could these voters be wooed back to the Democratic camp by an anti-TCJA campaign message?

Still, the swing voting population is not zero; about 9 percent of Obama voters supported Trump in 2016. Could these voters be wooed back to the Democratic camp by an anti-TCJA campaign message? Some experimental research has suggested that lower income Republicans, provided with more information about the effects of tax policy, change their positions to support progressive policies. Although Obama-Trump voters are, unsurprisingly, the most conservative Obama voters, they come closest to mainstream Democratic positions on economic issues like the minimum wage. That said, a variety of studies suggest that Obama-Trump voters were motivated by deep fears of losing status in an increasingly multicultural country. It is not obvious that a campaign on tax policy would address these fears. It is possible to imagine that an anti-TCJA campaign, in the style of Bernie Sanders, might appeal to a minority of lower-income Trump voters. But this is highly speculative. In a partisan political moment, the parties are wise to focus on ensuring the turn out the occasional voters in their political base.

Legislation as a partisan mobilizing tool

If the TCJA is unlikely to coax many voters away from their partisan commitments, one might think that major legislation would at least mobilize partisans. As we have seen, a comfortable majority of Republicans supported the legislation; perhaps Republican campaigns can convert that support into greater electoral enthusiasm in November. Alternatively, Democratic candidates might find the TCJA a useful campaign issue, if grassroots opposition to regressive tax cuts were to translate into greater Democratic electoral engagement.

There are good reasons to doubt the mobilizing power of the TCJA for Republican candidates in 2018. During and after the legislation’s passage, Republican voters’ support for the TCJA not exactly full-throated. In 2017, tax reform was not a top priority for voters, or even for rank-and-file Republicans. The major provisions of the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” are also at odds with the longstanding preferences of most Americans, including most Republicans.

There are good reasons to doubt the mobilizing power of the TCJA for Republican candidates in 2018.

At the height of the debate over the tax bill, a miniscule fraction—between 1 and 2 percent of the American public—listed “taxes” as the most important problem facing the country. A point of comparison: When the Affordable Care Act was the top priority of the Obama White House in the fall of 2009, health care was seen as the most important problem by 26 percent of the public, second only to the economy. Even as their leaders prioritized an enormous tax cut, the public (including rank-and-file Republicans) did not see this issue as especially urgent.

The specifics of the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” ran counter to the preferences of most Americans, including the preferences of most Republican voters. The law provides large tax cuts to corporations and to wealthy people, but almost three quarters of Americans, including a majority of Republicans, thought that corporate tax rates and taxes on those making over $250,000 a year should be raised or kept the same. In fact, the legislation worsened what most Americans see as the primary problem with the federal tax system. When asked what bothers them “a lot” about the tax system, about three-fifths of Americans say corporations and the wealthy not paying their fair share. Even among Republicans, underpayment of taxes by corporations and rich people is a bigger concern than their own tax rates. Only about a quarter of Americans, and 35 percent of Republicans, say they are bothered “a lot” by the amount of taxes that they pay. Most Republicans do not think they pay more than their fair share in taxes.

In cutting taxes for rich people and corporations, the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” implemented the opposite of most Americans’—and most Republicans’—preferred tax policy. Tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations are not popular even with Republicans, nor were Republicans clamoring to see their own taxes reduced.

It is reasonable to ask: So what? A disconnect between public priorities and legislators’ actions is far from uncommon. Nebulous public opinion does not drive policy outcomes; policy is made by organized interests operating within the constraints of U.S. political institutions. If majority opinion led inexorably to policymaking, the 115th Congress would have passed universal background checks for gun buyers and a higher minimum wage, not a large corporate tax cut. What is surprising, then, is not that legislative priorities were determined by legislators, but rather that very high levels of elite Republican attention to tax policy failed to bring rank-and-file Republicans to see the issue as important, or to shift Republican attitudes in favor of the substance of the legislation.

Of course, legislators gave voters (and policy experts) exceptionally little time to assess such a complex and far-reaching piece of legislation. Introduced on November 2 and signed into law less than two months later, the tax bill was the subject of no public hearings. The TCJA was written so quickly and with so little public oversight that prominent tax lawyers took the unusual step of issuing a series of papers “describing some of the major games, legal roadblocks, and glitches in the legislation.” The decision by Republican leadership to shield an unpopular piece of legislation from scrutiny also presumably limited the opportunity for grassroots Republicans to become enthused about the bill, if such enthusiasm were possible.

That said, Republican leaders have invested tens of millions of dollars in promoting the TCJA, both during its development and since its passage. The American Action Network, a policy group aligned with House Speaker Paul Ryan, spent $2.5 million on tax reform ads in 29 districts, as of December 2017, and committed to spending $22 million overall in support of the TCJA. The Republican National Committee reported that its affiliates had knocked on over 364,000 doors to promote the TCJA in battleground states like Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Ohio. The billionaire conservative Koch brothers, working primarily through their advocacy organization Americans for Prosperity, committed $20 million to promote the tax bill in the fall of 2017 and an additional $20 million to promote the benefits of the law ahead of the midterm election.

In cutting taxes for rich people and corporations, the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” implemented the opposite of most Americans’—and most Republicans’—preferred tax policy. Tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations are not popular, even with Republicans.

To date, the effects of this effort seem to be few. Over the course of the bill’s consideration, most Republican voters did not expect to see a personal benefit from the bill, nor did they report seeing an income increase in the months after the bill became law. (Overall, less than a quarter of Americans expected to benefit personally from the tax bill, or perceived an income bump after the TCJA became law.) As the second figure demonstrates, Republican support for the legislation has not noticeably increased. Attention to the tax bill has also declined in recent months.

Republicans working in off-cycle campaigns this spring seem to have already recognized the limited value of the TCJA as a campaign issue. After initially investing heavily in ads about the new tax cut, Republicans in Pennsylvania all but abandoned the issue in the final weeks of the campaign. By all indications, the TCJA will not be an especially effective mobilizing tool for Republicans in the 2018 election.

In fact, it is probably more accurate to say that partisanship shored up grassroots Republican support for the tax bill, rather than that the tax bill will spur Republicans to more fervent support of the party. We can get a sense of this effect by looking at how Republican support for the tax bill varied with survey question wording.

When asking Americans whether they supported or opposed the tax bill, some pollsters informed their respondents that the legislation was supported by President Trump or the Republican Party, while other surveys did not. For instance, a January 2018 NPR poll asked “From what you have seen or heard, do you favor or oppose the recently passed tax bill?” A February 2018 survey conducted for Politico asked, “Based on what you know, do you support or oppose a bill of widespread changes to the tax system recently signed in to law by President Trump?”

Looking across these polls, we find that Republicans appear to respond strongly to partisan cues about the tax bill. When respondents were informed that the tax bill was supported by Trump or the Republican Party, 76 percent of Republicans were in favor of the legislation. When a pollster asked respondents about the tax bill without a partisan reminder, 68 percent of Republicans expressed support. That is to say, when survey questions mentioned the president or the Republican Congress as the proponents of the TCJA, Republican support was about 8 percentage points higher.

Republicans working in off-cycle campaigns this spring seem to have already recognized the limited value of the TCJA as a campaign issue.

Interestingly, given the extremely negative views they hold of President Trump and of Republicans, Democrats were no more likely to oppose the legislation when a survey question mentioned Trump or the Republican Party. In survey questions providing a partisan cue, 11.6 percent of Democrats supported the tax bill. In survey questions without a direct reference to Trump or the GOP, nearly the same percentage of Democrats endorsed the tax bill: 11.4 percent. The results are not conclusive, but they suggest that partisanship played an important role in reinforcing Republican attitudes about the TCJA, in a way not evident among Democrats.

If Republicans are unlikely to see much additional mass mobilization thanks to the TCJA, the story could be different for Democrats. Democrats’ support for progressive tax policy is in line with their party’s position on the TCJA, which would plausibly make it easier to use this issue as a mobilizing tool. Given the very high levels of political engagement Democrats have evinced during the Trump presidency, it might seem implausible that the TCJA would have a measurable impact on Democrats’ mobilization in 2018. But in at least one recent case, a single controversial piece of legislation demonstrably aided the out party in an already highly engaged year.

Voting for the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 was costly for Democratic incumbents in competitive districts that fall. Swing district Democrats who voted for the ACA performed about 6 percentage points worse than comparable Democrats who voted against the legislation. The overall impact was substantial; the passage of the ACA is estimated to have cost Democrats 25 seats in the House.6 Polling data suggests that this impact stems from a change in the attitudes of Republican constituents, who came to see their Democratic representatives who had supported the ACA as more liberal and more out of step with their own views.

Could the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act be the Republicans’ Affordable Care Act? There are certainly political parallels. Attitudes about the ACA were a mirror image of the TCJA; 12 percent of Republicans favored the legislation, compared to 61 percent of Democrats. The roll call votes were also similar, with absolute opposition from the minority party and only a small number of defections from the majority party. But controversial and partisan pieces of legislation do not always result in electoral blowback. For instance, Democrats do not appear to have suffered as much electorally in voting for the economic stimulus bill known as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

When does a piece of legislation result in electoral damage to the legislating party? The difference may well be the political commitments made by party leaders. Opponents of the ACA spent at least $108 million dollars on advertisements against the legislation, about six times the amount spent by supporters of the bill. Democrats’ fall campaigns will probably not feature the TCJA in a manner similar to the Republicans’ 2010 assault on the Affordable Care Act, a decision likely influenced by the preferences of elite party members and donors. Which brings us to the final way in which the TCJA might influence the 2018 election: by its impact on campaign spending.

The political power of business and the donor class

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act provides a tremendous windfall for the already wealthy. The top 1 percent of earners can expect to take home, on average, an extra $51,140 each, according to the Tax Policy Center’s calculations. One potential electoral effect of the TCJA, therefore, could be its impact on the political behavior of the rich, who make up the law’s primary beneficiaries and who provide a growing percentage of campaign resources. The wealthy will both have more money as a result of the TCJA, and—for some—more incentive to engage in politics.

If the TCJA were to influence the campaign donation patterns of wealthy people, it would likely redound to the benefit of Republicans. First, though there are rich people in both the Democratic and Republican parties, wealthy people are more likely to be Republicans. Second, the cap on the state and local tax deduction in the TCJA was intentionally structured to provide less of a tax cut to wealthy people in high-tax blue states, where many rich Democrats reside. Finally, the wealthy are economically conservative, so the political incentive created by the legislation is more likely to motivate Republican donors to support their party, rather than to encourage Democratic donors to invest more than they otherwise would. News reports confirm that some Republican donors did threaten to withhold their campaign support if a tax bill were not passed.

The wealthy will both have more money as a result of the TCJA, and—for some—more incentive to engage in politics.

We cannot know, of course, the benefit Republicans saw to their campaign coffers due to the passage of the TCJA, or, counterfactually, how much donors would really have punished Republicans for a failure to pass the law. In thinking about the impact of any TCJA-inspired donations in 2018, however, it is important to recognize that money does not always buy electoral success.

In fact, though having a spending advantage during the campaign correlates with winning the election, political scientists have struggled to identify a clear causal connection between spending more money and winning more votes. How can that be? First, there are the confounding factors: many traits that make a candidate successful with voters (like charm, strong community ties, or a famous name) also make them successful with donors. Then there is the chicken-and-egg problem, as donors often jump on the bandwagon of an already successful campaign. Finally, a truly extraordinary amount of campaign money is wasted.

For all of these reasons, the most rigorous analyses tend to find a limited impact of money on elections. Campaign spending seems to matter mostly for challengers, not incumbents, because challengers typically need to spend money to increase their name recognition. Incumbents tend to be better known at the start of the campaign, and therefore quickly experience diminishing returns for additional campaign dollars spent.

This is not to suggest that money does not influence politics—quite the reverse. There is robust evidence that the political system as a whole protects the interests of the rich. When the preferences of the upper class diverge from those of lower- and middle-class people, policy outcomes mostly follow the desires of the wealthy. Experimental evidence has shown that senior policymakers in Congress are three times more likely to make themselves available for a meeting with a donor than with a constituent. People from working class backgrounds are enormously underrepresented in elected office. American political life is shaped by the power of the economically privileged.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to enumerate the many avenues by which wealth sets the political agenda. But the paradoxical result may be that campaign contributions, by themselves, are less significant that one might assume. In the aggregate, economic power translates into political power—so much so, perhaps, that the marginal campaign dollar, often misspent, has an immeasurably small impact.

The upward redistribution of the TCJA will accelerate the already immense economic inequality in the United States, and provide the economic elite with additional resources by which to shape American political life.

It is not obvious how much the passage of the TCJA increased donor contributions to Republican campaigns in 2018, and the marginal effect of these funds for incumbent candidates is probably small. It is over the longer term that there are real implications of the TCJA for the political power of the wealthy.7 The upward redistribution of the TCJA will accelerate the already immense economic inequality in the United States, and provide the economic elite with additional resources by which to shape American political life.

Why the TCJA?

As we’ve seen, a regressive tax cut was not a priority for rank-and-file Republican voters, and will have only marginal economic stimulus effects. While the TCJA may have unlocked additional campaign funds for Republicans, political science would suggest that an incumbent’s re-election chances are not much improved by their fundraising. So why did Republican legislators see the passage of the TCJA as so urgent?

One explanation is simply that political scientists are wrong to discount campaign spending. Perhaps we do not have the data we would need to really assess the question. We have little evidence about the financial hit legislators might expect to take for alienating their wealthy benefactors because, by and large, legislators do not alienate their wealthy benefactors. We can only make predictions based on the range of data available, so if almost all candidates focus on high-dollar fundraising, we cannot say much about what would happen if candidates did not do so.

Alternatively, it may be that Republicans made an error in their political calculus. Legislators are not infallible strategic thinkers; we know, for instance, that members of Congress systematically misperceive the political inclinations of their constituents. Because legislators’ tend to see their constituents as more conservative than they really are, Republican elected officials might not have recognized just how little the tax cut was going to appeal to their base.

By the same logic, it could be that legislators feel more beholden to their donors than they actually are. It is certainly widely believed that the passage of the TCJA unlocked “millions for a Republican election blitz,” as the New York Times described it. Given the large percentage of elected officials who are themselves wealthy, the social pressure from donors may have been substantial, whether or not legislators really feared a reduction in donations and concomitant damage to their re-election bid.

Finally, legislators may have supported the TCJA out of long-term ideological or strategic commitment, rather than short-term electoral considerations. If one wished to hasten the concentration of wealth at the very top of the economic distribution, the TCJA is an effective mechanism to achieve that end. In addition, regressive tax cuts have in the past created deficits that were used to build political pressure to reduce spending on the social safety net. So those who would wish to reduce public spending on popular beneficiaries like children, the sick, and the elderly, might find the TCJA a useful vehicle toward that end.

These explanations are not mutually exclusive, of course. It may be that Republican legislators misjudged the preferences of their base, and that support for the legislation was buoyed both by ideological commitment and donor pressure. It is easy to imagine that the motivation to pass the TCJA was strengthened precisely because the legislators’ ideological views and perceived self-interest coincided.

Conclusion

Given the deeply polarized political context, the TCJA is unlikely to shift many voters from their partisan camps. Voters are also highly unlikely to respond to any small increases they see in their take-home pay. If the TCJA has a stimulative effect on the economy as a whole, it will be small and the electoral benefit will be negligible in the midterm election. The evidence suggests it could be fruitful for Democrats to capitalize on opposition to the TCJA to mobilize their base. But on balance, it is unlikely that party leaders will avail themselves of that political opportunity to the extent Republicans did in their 2010 response to the Affordable Care Act. In the longer term, the TCJA funnels substantial resources to the Republican Party’s donor class, a process that will plausibly make American politics even more oligarchic.

Appendix: Surveys cited

| Source | Survey Start Date |

| ABC News / Washington Post | 9/18/2017 |

| ABC News / Washington Post | 9/26/2017 |

| CBS News | 3/8/2018 |

| CNN / SSRS | 10/12/2017 |

| CNN / SSRS | 11/2/2017 |

| CNN / SSRS | 12/14/2017 |

| Economist YouGov | 1/28/2018 |

| Economist YouGov | 2/4/2018 |

| Economist YouGov | 2/11/2018 |

| Economist YouGov | 3/4/2018 |

| Economist YouGov | 4/8/2018 |

| Economist YouGov | 5/6/2018 |

| Economist YouGov | 5/20/2018 |

| Gallup | 12/1/2017 |

| Gallup | 1/2/2018 |

| Gallup | 4/2/2018 |

| HCAPS | 11/11/2017 |

| Monmouth | 12/10/2017 |

| Monmouth | 1/28/2018 |

| Monmouth | 3/2/2018 |

| Morning Consult | 9/29/2017 |

| Morning Consult | 10/26/2017 |

| Morning Consult | 12/14/2017 |

| NBC News / WSJ | 12/17/2017 |

| NBC News / WSJ | 1/18/2018 |

| NBC News / WSJ | 4/8/2018 |

| NPR / PBS | 1/8/2018 |

| Pew | 1/10/2018 |

| Politico | 2/15/2018 |

| Public Policy Polling | 3/23/2018 |

| Quinnipiac | 11/15/2017 |

| Quinnipiac | 11/29/2017 |

| Quinnipiac | 12/6/2017 |

| Quinnipiac | 2/2/2018 |

| Quinnipiac | 3/3/2018 |

| Quinnipiac | 3/16/2018 |

-

Footnotes

- The far more substantial effect of the TCJA on middle-class households is the repeal of the Affordable Care Act’s individual mandate. The change is projected to result in 4 million Americans losing health insurance by 2019, even though voters will still face a tax penalty for failing to obtain health insurance in 2018. Insured Americans can expect premiums to increase by about 10 percent a year. But these costs will mostly not be felt until after Election Day.

- Nonetheless, some researchers include an economic indicator in their midterm election forecasts.

- Of course, some people do switch parties, but this is often in response to policy changes that activate extremely deeply held social identities, like race and ethnicity. For instance, the Democratic Party saw a 17 percentage point drop among white voters in the American South between 1958 and 1980, a period in which national party leaders came to support Civil Rights. There is some partisan switching today, likely driven by changing party commitments regarding race and immigration. Between 2011 and 2017, an estimated 5 percent of voters switched their partisan affiliation from one major party to the other.

- The survey trends reported here are based on the author’s compilation of 56 survey questions asked about the TCJA and its legislative precursors in 36 nationally representative polls conducted by fifteen major survey organizations between September 2017 and May 2018.

- These results include polls from different survey organizations that use somewhat variable question wording, such as asking respondents if they “support/oppose” or “approve/disapprove” or “favor/oppose” the legislation.

- This calculation from Nyhan et al. is based on the counterfactual premise of more Democrats in competitive districts voting “no” and therefore performing as well as the Democrats who did vote no. There are important limits to this counterfactual, however, because – as the authors point out: “The real political world is more dynamic. We have no way of knowing, for example, whether more Democratic dissent in the House would have doomed the health care bill and thereby led voters to see the Obama presidency and Democratic Congress as failures. It is also possible that the failure of health care reform would have demobilized some Democratic donors, interest groups, and voters in 2010.”

- For instance, wealthy conservatives have invested in party-like organizations that engage in policymaking, advocacy, and voter contact operations, and operate on a scale similar to the Republican Party. The electoral impact of such enormous investments in an independent political infrastructure is likely to be sizeable over the long term.