As politicians and pundits debate the merits of “Bidenomics,” one part of the administration’s economic strategy deserves special attention: the significant investments in “place-based” policies designed to boost growth in particular locations.

Among these new investments is the Distressed Area Recompete Pilot Program, authorized in the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act. This initiative is aimed at funding distressed local labor markets to bolster their prime-age (25- to 54-year-olds) employment rates.

The Recompete program is based in part on research by one of the authors of this piece (Timothy J. Bartik), developed for Brookings Metro and expanded on in a later report. Though altered from its initial concept due to political realities and negotiations, Recompete retains the core objectives those reports originally laid out by advancing a new approach to helping distressed places.

This June, the federal Economic Development Administration (EDA) posted a “Notice of Funding Opportunity” (NOFO) for Phase 1 of Recompete, so it’s worth discussing what is new about the program, what can be learned from it, and how to expand it in the future. Ideally, such considerations will help the nation make the most of the program so that it will continue to help all distressed places rather than being a one-time effort.

Breaking down the basics of the Recompete program

The Recompete Pilot Program will invest $200 million in a few persistently distressed communities to create and connect people to good jobs. To do so, the program targets areas where the prime-age employment rate significantly trails the national average, with the goal of closing this gap through large, flexible investments.

The program got its start in Congress with the RECOMPETE Act, which Rep. Derek Kilmer (D-Wash.) introduced in 2022. That legislation would have provided $175 billion in funding over 10 years to most of the country’s distressed places, after some basic screening requirements.

A scaled-back version of this proposal was later enacted as part of the CHIPS and Science Act, with authorized (but not appropriated) funding of $1 billion. Subsequent appropriations further trimmed the program, to $200 million. With this drastically reduced funding, Recompete changed from a formula program with sufficient funding for most distressed places to a pilot program providing competitive discretionary grants to only a few distressed places.

Phase 1 of the pilot program is a planning phase. Out of the $200 million total, the EDA anticipates awarding approximately $6 million to $12 million during this phase. This will provide local entities with strategy development grants for planning, with a typical grantee receiving $250,000 to $500,000. Local entities may also apply for approval of a “Recompete Plan” during Phase 1; approved plans are necessary for applying for implementation funding during Phase 2. Entities may apply for strategy development grants without applying for Recompete Plan approval if they decide they are not yet ready for implementation funding. Places may also choose to apply only for approval of a Recompete Plan without applying for a strategy development grant.

Phase 2 of the program will allow communities to move on to implementation. Out of the 20 or more Recompete Plans to be approved in Phase 1, the EDA anticipates selecting four to eight applicants for implementation funding in Phase 2. Implementation grants will average $50 million for entities that apply on behalf of distressed local labor markets and $20 million for entities that apply on behalf of distressed local communities. Recompete Plans and implementation funding will typically support three to eight projects aiming to increase the prime-age employment rate within eligible distressed places, with projects anticipated to have a “period of performance [that] does not exceed five years.” Recompete Plans may seek to increase the prime-age employment rate throughout the entire distressed place or only of portion of it, such as a particular set of neighborhoods. The Phase 2 NOFO is expected to be released this winter.

In short, as the word “pilot” suggests, Recompete is being run at a small scale. Given that, we should ask: How can the EDA best run this pilot so that they can build on it to develop a more comprehensive, large-scale program that helps all of the country’s distressed places? What potential is there for designing the pilot so that we can learn which approaches to helping distressed places are most effective? And what should be done in this pilot to increase the odds of political support for a larger-scale program?

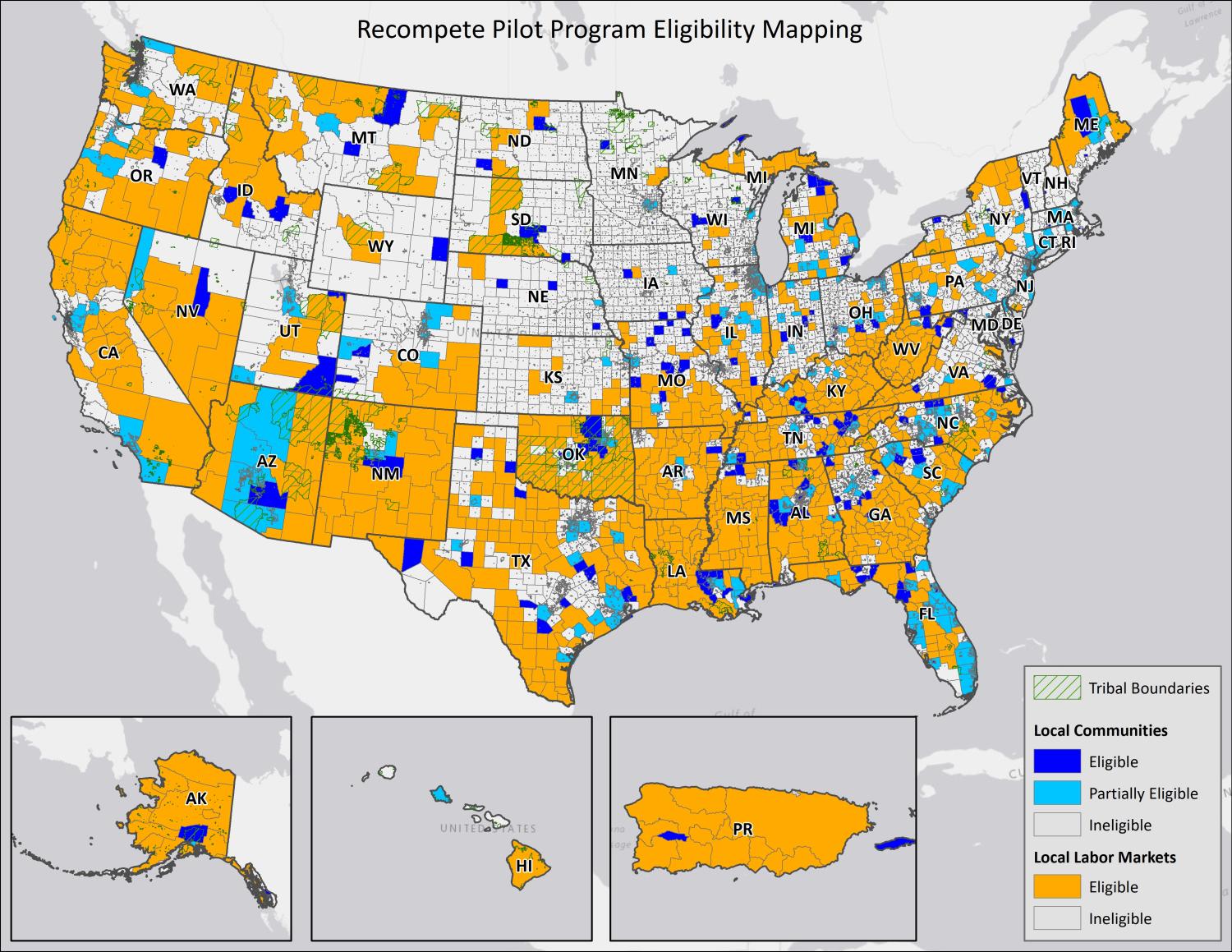

Map provided by: EDA, Recompete Pilot Program, and Argonne National Laboratory. Full interactive map available here.

Recompete offers a new approach to helping distressed places

Before considering the above questions, it’s important to highlight the features that make the Recompete program unique in its approach to economic development in distressed places:

A focus on making sure jobs are filled by local residents

Past economic development programs often focused only on job creation. But it is not enough just to create jobs in distressed places. In contrast with past programs, Recompete is also concerned with who gets the jobs.

Research justifies this focus: Even in distressed places, less than half of new jobs will end up increasing the local employment rate, with the remainder going to in-migrants.

In contrast, Recompete is specifically focused on increasing the prime-age employment rate in local labor markets and neighborhoods where that rate is far below the national average. The prime-age employment rate roughly controls for a place’s age mix (e.g., whether a place has many students or retirees). In addition, society generally expects the prime-age population to work; higher employment rates in this group promote stronger families and improved child development. Past programs to help distressed places have often been vague about what they are meant to achieve, unlike Recompete’s specific goal of boosting the prime-age employment rate.

Creating jobs through business services instead of tax incentives

Many past economic development programs have sought to create jobs by providing business tax breaks or other cash incentives, mostly going to large businesses. In contrast, Recompete provides a variety of business services and infrastructure, including customized job training for individual business needs; business advice on adopting new technology and finding new markets; and business infrastructure such as research parks.

Customized business services like these create jobs at one-third the cost of tax incentives. And emphasizing them broadens economic development to include more small businesses and entrepreneurs. Some services—such as entrepreneurial training and small business incubators—are specific to small businesses. Others—such as customized training and business advice—may be more useful to small or medium-sized businesses that may lack adequate knowledge and resources.

Providing job access, not just training

The Recompete program’s services go beyond just job training. It will also provide residents with reliable used cars, wrapround services such as child care, and success coaches to improve job retention. Such services have been shown to make training more effective, and respond to the reality that disadvantaged people who need better jobs face problems beyond a lack of adequate skill credentials. Additionally, these job-access services can be coordinated at the neighborhood level, sometimes by case workers at trusted neighborhood institutions who can link individuals to the services they need.

Beyond funding more customized services to individuals, Recompete will also fund more systemic solutions; for example funding “local transportation agencies [to remove] physical barriers to job opportunities by increasing access to and convenience of public transportation,” according to the NOFO.

Reforming employment practices instead of working within the existing system

Past programs to boost employment often simply provided subsidies and services without necessarily changing how private employers and governments make hiring decisions. In contrast, the Recompete NOFO says the program expects “local action to change or reform policies [and] practices…that make it harder for people to access work.”

As an example, the NOFO mentions that “anchor institutions such as firms, hospitals, and universities” might work to eliminate four-year degree requirements for certain occupations. An applicant’s Recompete Plan might also include “private-sector commitments to recruitment in a particular distressed neighborhood.”

Flexible investment that fits the local context

Under normal federal funding procedures, a distressed local community would have to apply to multiple federal agencies with various rules and restrictions to pull together support for a comprehensive plan. But preparing and submitting multiple applications is a huge burden on a distressed community, especially one with limited capacity.

Multiple funding streams also make it difficult for federal support to be optimized to fit local needs. As the Recompete NOFO recognizes, distressed places differ enormously in whether they need to emphasize more good jobs in total or more access to good jobs that already exist. So, the program allows a local community to apply for a single grant that can be used for all kinds of things, including both job creation and job-access services. In this way, Recompete allows places to optimize their economic development strategies to meet their most pressing local needs.

How policymakers can judge the success of Recompete

While Recompete’s novel approach raises the possibility of improved outcomes, it doesn’t guarantee them. To eventually learn whether Recompete “works,” we must measure the program’s effects in the four to eight places that receive grants compared to the places that don’t. In that way, policymakers can ascertain whether the pilot made a substantial difference in improving residents’ employment and earnings. Without such evidence, it is difficult to support expanding Recompete to a large enough scale to help most of our country’s distressed places.

Furthermore, policymakers can and should use this pilot to learn which strategies work best in different places. Such lessons could guide any large-scale expansion of Recompete.

Two factors would increase the likelihood of statistically detecting Recompete’s benefits:

- A larger amount of program benefits for residents of places that receive grants.

- A larger sample size of places that receive grants and plausible comparison places.

In the Recompete NOFO, the EDA has done a good job—within the constraints of program funding—to make it more likely that the pilot will yield meaningful evaluation evidence. For example, the EDA implies that funded places should be able to show large effects on the local employment rate: “[T]he eligible entity [should have] a multi-year plan for reducing the [prime-age employment gap] of the eligible area with a strong probability of success.”

Under this funding process, the best evaluation option is what is called a “quasi-experimental control trial.” In this scenario, the four to eight places that receive funding would be compared to unsuccessful applicants that have similar features and prior trends. After the implementation grants are spent, evaluators can see if funded places differ in employment, earnings, or other quantifiable trends. An ideal evaluation would consider trends a few years after the end of the five-year performance period for funded implementation projects, to study the longer-term effects of funded projects.1 As a precedent, an evaluation of the Empowerment Zone program detected statistically significant effects between funded places and comparison places.

The Recompete pilot’s limited one-time funding complicates assessment and learning

Learning from the Recompete pilot evaluations is critical, but it will be hampered by the modest size of the program’s one-time funding. With only $200 million, the EDA cannot ensure the program will have substantial effects in larger distressed places. Such effects may be feasible for neighborhoods or smaller communities, but not for a large city.

Consider the possible effects of an individual grant. In the NOFO, the EDA says that grants to distressed local labor markets will average $50 million per grant and grants to distressed local communities will average $20 million per grant. Optimistically, the maximum possible effects of such grants on prime-age employment rates might result in one extra job for a prime-age person for an extra $50,000 in spending.2 Therefore, a Recompete grant of $50 million or $20 million would at most increase employment of a place’s prime-age workers by 1,000 or 400 persons, respectively ($50 million divided by $50,000 is 1,000; $20 million divided by $50,000 is 400).

This increase could be large for a neighborhood or smaller community. Suppose the targeted place consists of five census tracts, with a total population of 20,000 people. Prime-age persons average 39% of the population, so this neighborhood might have 8,000 prime-age persons. An increase of 400 extra employed prime-age persons represents a 5-percentage-point boost in the prime-age employment rate, which is large.

However, in larger communities, increasing prime-age employment by even 1,000 jobs would not boost the prime-age employment rate by much.3 Even if Recompete’s benefits exceeded costs, the effects on prime-age employment rates would not be statistically discernible to researchers or readily apparent to policymakers.

The EDA could avoid this problem by providing implementation grants only to rural and other smaller communities, or to larger communities if the targeted place is a smaller neighborhood within it. From an optimistic point of view, if almost all the four to eight grantees ran their programs well, the $200 million in pilot funding could provide the Recompete program with a “proof of concept” that this approach can work.

However, this optimistic view overlooks the fact that even in smaller communities and neighborhoods, the effects of implementation grants will be harder to detect if some of the Recompete Plans are poorly implemented. Persistent increases in local prime-age employment rates have a large social benefit. The present value of the increased per capita earnings from higher employment rates and higher wages, along with other local spillover benefits, could exceed $500,000. If an average Recompete grantee ends up increasing prime-age employment rates at a cost of $250,000 per job, the program might have a high benefit-cost ratio, yet the effects would be hard to detect with modest grants to only four to eight places.

This optimistic view also overlooks the fact that with only four to eight grantees, learning what strategies work best in different places is almost impossible. With such a small number of grantees, the variation in strategies and place characteristics is insufficient to learn how to improve and customize Recompete strategies.

Therefore, due to the limited funding, there is a risk that the nation will not be able to authentically test the Recompete concept to see if it works. Even if the program’s true benefits exceed its costs, it might not have large enough effects to be discernible. Political opponents can claim the program doesn’t work because estimated effects are “statistically” insignificant. The EDA can try to avoid this problem by limiting the program to smaller communities or neighborhoods, but even that limitation might fail to result in statistically detectable effects.

More funding for Recompete would help reveal what works

More funding for Recompete could make it easier to detect the program’s effects, either by increasing the effects per place or increasing the number of funded places. Greater effects are likelier if each EDA-funded place receives supplemental funding. Funding more places obviously would also require more funding.4

In addition, from a political perspective, policymakers should make sure that funding levels for the pilot are large enough to have community effects that are readily discernible by both local and outsider observers. Readily discernible effects will help the program gain political support.

For example, if we want to double Recompete’s effects in boosting the prime-age employment rate, we might want to double the program’s funding levels for the four to eight chosen places.5 That is, the $50 million average per local labor market would be doubled to $100 million, and the $20 million average per local community would be doubled to $40 million. This doubling of grants per place would require doubling support for Recompete’s chosen places from the current $200 million to $400 million.

Adding more funded places would also help policymakers discern what strategies work best in which types of places. If we tripled or quadrupled the number of places, more diversity in local conditions and strategies would emerge. What works best, and where, could be evaluated.6

To that end, an expansion of the pilot by $400 million or $600 million dollars—which would support a tripling or quadrupling of the number of funded places—would greatly improve the quality of evaluations of the program and potentially do much to enable further expansion.

Ideally, the nation would embrace both expansions: Expand funding per place so effects are more likely to be statistically and politically discernible, and expand the number of funded places so that both the program’s overall effects and the variation of effects across places are statistically discernible. With better-quality evaluation evidence, an expanded Recompete pilot might lead to the political adoption of similar programs at a large enough scale to help more of the country’s distressed places.

Even with expanded pilot program funding, the EDA would probably be wise to restrict implementation grant funding to smaller communities or neighborhoods. For a larger metro area or city, the funding required to have a substantial effect would probably be close to $500 million.7 And even if the pilot’s funding was expanded to $1 billion, it would only allow grants to a couple large metro areas or cities. With such a small group, statistical analysis would find it difficult to tell whether any observed effects were due to the Recompete or to idiosyncratic place characteristics.

Possible sources for additional Recompete funding

The above argument raises the question of how this dual expansion of the Recompete pilot could conceivably be funded. Possible sources include future federal appropriations, local funds, current federal funds, state governments, and large philanthropic institutions.

The first obvious recommendation is for Congress to appropriate an added $800 million to fund the Recompete Pilot Program at its authorized $1 billion level from the CHIPS and Science Act. With the added $800 million, the EDA could expand both funding per place and the number of funded places. Such funding would reduce the risk that the pilot will yield no usable results. However, given the current political climate and federal deficits, an additional federal appropriation for the pilot seems unlikely.

As for local funding, the Recompete NOFO mentions that in awarding implementation grants, “matching dollars will be considered” and that “Recompete Plans should demonstrate how other public…dollars may be leveraged to support the effort.”

If a community can match the EDA’s $20 million or $50 million with an added $20 million or $50 million in local dollars, then this combined federal-local package is more likely to have discernible effects. However, distressed places, almost by definition, tend to have below-average local tax bases. Therefore, the distressed places that need the most help will have the most trouble coming up with a local match.8

As for funding more places, the EDA’s Recompete Pilot Program FAQs mention that the agency is seeking ways to channel unspecified additional support to communities that have had their Recompete Plan approved but not won an implementation grant.

However, given legislative and regulatory restrictions on other federal programs, other federal funding may not have the needed flexibility to fully support a Recompete Plan. In theory, program waivers to allow for more flexible uses could be granted; in practice, such waivers are unlikely to occur.9

More funding for the initial four to eight places or additional distressed places could be provided via state governments. For additional places, state government grants could simply adopt the EDA’s criteria for distressed places, the eligible funding categories, and even the funding process. Alternatively, state governments could simply decide to fund some of the Recompete Plans that do not receive implementation grant funding.

Along these lines, many wealthy states (such as New York and California) have large, distressed regions (think of Upstate New York and the Inland Empire in California). These wealthy states could readily afford to do more to help their distressed places.

Historically, however, state governments have found it hard to target large resources toward distressed places. For example, a recent study of large states found that the percentage of economic development program resources that had some targeting was generally 11% or less. Even if an economic development program had some targeting, typically less than half of the funding actually went to distressed places.10

State governments find it difficult to target distressed places because such places tend to lack political clout. It’s easier to let economic development dollars flow to where jobs are being created anyway.

Alternatively, large philanthropic institutions could play a significant role in increasing the size of the Recompete pilot. As mentioned earlier, distressed places often lack local resources; philanthropies could overcome this gap by supplementing the EDA grants. Such resources might be particularly needed for places with larger employment problems.

Large philanthropic institutions could also fund additional places using Recompete’s approach. This could either be done on their own or in cooperation with state governments.

Philanthropic institutions’ key advantages are targeting and flexibility. Many philanthropies are interested in targeting resources toward the areas of greatest need, which should be appropriately defined as including the residents of distressed places. And it may be easier for philanthropies to achieve flexibility compared to the federal or even state governments.

If one had to choose where added funding is most needed, the top priority would be to make sure the four to eight EDA implementation grant recipients achieve large benefits for residents. Only if Recompete “works”—both in perception and in reality—will there any strong justification for expanding its approach.

Once funding is adequate to get substantial effects per aided place, more funding could expand Recompete to other places. These new places should have diverse characteristics and strategies, to allow for lessons.

Moving Recompete from a one-time pilot to a new model

The Recompete Pilot Program is a promising new approach to improving the employment prospects of residents of distressed places. The approach is characterized by flexibility to meet diverse local needs and addressing both job creation and job access.

But in the current federal appropriation, this new approach only receives limited funding for a few distressed places. Helping all distressed places in the U.S. would require expanding funding by a thousand-fold.

Supplementing the pilot funding could enable policymakers to better build on the experience of the Recompete pilot. The top priority should be to provide sufficient funding per distressed place to have discernible benefits for residents. If further funding permits, we should expand the pilot to other distressed places that have different needs and require different strategies.

In short, if the Recompete Pilot Program is to be more than a one-time discretionary grant program, its funding must be sufficient to give a fair chance for it to show benefits. Only demonstrated benefits will generate support for expanding the Recompete approach to a large enough scale to help all of the country’s distressed places.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors wish to thank Rob Maxim for editorial support.

-

Footnotes

- Other evaluation options include comparing the four to eight funded places with the 12 to 16 places that had approved Recompete Plans but did not receive implementation grants. Another option could be based on the EDA’s numerical scoring of Recompete Plans. Places with high scores that just missed Recompete Plan approval also could be a comparison group. In either case, one issue is that places with well-developed Recompete Plans may receive other funding. In addition, the development of good Recomplete Plans could be considered part of the program’s effects. Finally, using all applications to select a comparison group—rather than just using approved or nearly approved Recompete Plans—would allow for better matching of the comparison group to the funded group on observable pre-trends. However, the availability of these alternative comparison groups does allow for robustness checks. As for sources of evaluation data, given the relatively small size of some funded places, evaluations should use data that sample a large percent of the population. Furthermore, the data should measure outcomes for persons originally residing in the funded places and comparison places. One possible data source would be confidential IRS data on earnings on tax returns for the original residents of these places.

- This is optimistic because Bartik (2022) calculates that the cost of local labor market job creation per additional prime-age job opportunity might have an average cost of $142,000 (footnote 63 on page 83). The cost of increasing prime-age employment rates due to job-access programs in neighborhoods might average $107,000 (p. 100).

- For example, suppose we wanted to detect a “modest” effect size on the prime-age employment rate of a local labor market. Bartik (2022) finds that the population-weighted standard deviation of the prime-age employment rate across U.S. local labor markets is 4.4 percentage points (Table 2, page 34). The conventional standard for a “medium” effect size is 0.5 (0.2 is “small,” 0.8 is “large”). Then we would need to increase the prime-age employment rate by 2.2 percentage points for a “medium” effect size (0.9 percentage points for “small,” 3.5 percentage points for “large”). If the prime-age population is about 39% of the total population, and a $50 million grant can boost the prime-age employment rate by 1,000 extra employed prime-age persons, then a “medium” effect size would require a local labor market of fewer than 117,000 persons (small, less than 291,000 population; large, less than 73,000 population).

- Which is better from a statistical perspective? Statistical precision is likely to vary inversely with the square root of the number of places in the funded group. As for funding per place, the increased ability to detect effects depends on how one thinks effects scale with funding. If effects scale more (less) than the square root of funding, then higher grant levels would contribute more (less) than adding places to making the effects detectable. Intuitively, increasing grant size might increase effects by faster than the square root at low or moderate levels of the grant amount, and at some large amount there would be sufficient decreasing returns to scale that effects scale at less than the square root.

- This implicitly assumes that program impact per place scales linearly with program funding per place. This seems a neutral assumption, but an assumption whose truth can only be tested via experience.

- If a sufficient number of funded places were added, quantitative evaluation might also be able to detect how effects differ across places and strategies.

- For example, suppose we consider a large metro area or city with a prime-age population of around 400,000. Such a place would have an overall population of about 1 million. A “medium” effect size (see prior footnote) for an increase in the prime-age employment rate would require a boost of 2.2 percentage points in the prime-age employment rate. This increased employment rate means that an extra 8,800 prime-age workers would need to get jobs (2.2 percentage points times 400,000). Under the optimistic assumption that we can increase prime-age job holding at a cost of $50,000 per job, the total cost of achieving this “medium” effect size is $440 million (8,800 times $50,000). These assumptions could be tweaked, but under most assumptions, the pilot could not support very many grants to large metro areas or cities that could achieve discernible effects on local employment rates.

- The EDA’s NOFO does say that “EDA will be cognizant of the different base levels of funding available in a region. An applicant will not be less competitive if there are simply fewer of these resources available to be leveraged.” Although this promotes fairness, less local matching will tend to lower substantive impact in the assisted place.

- The EDA also mentions that matches for the four to eight funded places may come from other federal agencies. A similar argument could be made here: Unless there is very liberal use of waiver authority, these federal matching funds may not fund what the local distressed place needs most to increase its prime-age employment rate.

- This discussion does not deny that there is some targeting, such as in California’s Community Economic Resilience Fund, or in some of the regional work from Empire State Development in New York. But the dollar magnitude of targeting—in the context of overall regional economic development resources—is typically modest.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).