Today, President Obama is marking the 50th anniversary of the historic March on Washington, led by civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. The March on Washington was for jobs, as well as freedom – indeed for the freedom that a job brings. Civil rights still have to be defended. Jobs have to be created and fairly allocated. But the most pernicious racial divide today is in social mobility: in the opportunity gap between a child born white, and a child born black.

It is true, in one sense, that class now matters at least as much as race. Racial gaps in education, employment and wealth reflect the disproportionate representation of black families at the bottom of the income scale. But an urgent question remains: why, in 2013, is the income distribution so skewed by race?

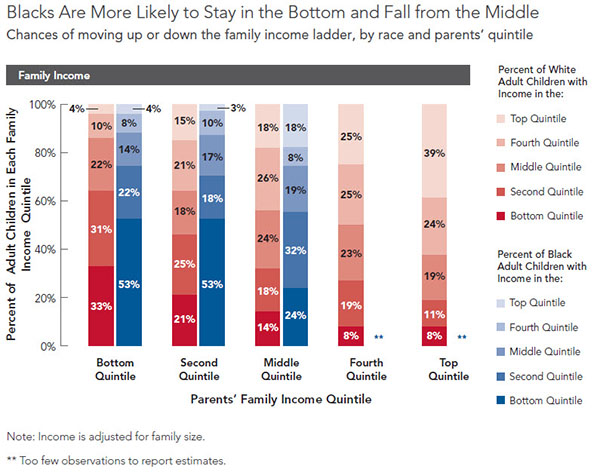

One answer is that black rates of upward social mobility are lower. Black children are more likely to be born into poverty than white children; but they are also less likely to escape. More than half of black adults raised at the bottom of the income scale remain stuck there as adults, compared to a third of whites:

Source: “

Pursuing the American Dream: Economic Mobility Across Generations

,”

The Pew Charitable Trusts, July 2012

Raj Chetty and his colleagues find that “rates of upward mobility are significantly lower in areas with a larger African-American population, such as the South”. Chetty argues that it is not race itself that is the causal factor, since he reports that whites living in the same areas also have lower mobility rates. But the children with narrower life chances in predominantly black areas are, by definition, predominantly black.

Dozens of other factors bear on the racial mobility gap, including continued discrimination in the labor market. Much is made of the greater incarceration rates of black men. But research produced by the William T Grant Foundation suggests that, in terms of job search, “black men who have never been incarcerated fare no better in the job market than white men just out of prison”.

Even ‘assortative mating’ – the tendency of affluent, educated people to marry affluent, educated people – has a racial gap, with implications for the intergenerational inequalities. According to data from Vida Maralani, 84% of highly-educated white women marry a well-educated man, compared to 49% of highly-educated black women. (The impact of assortative mating on mobility is a theme we’re going to return to shortly – watch this space.)

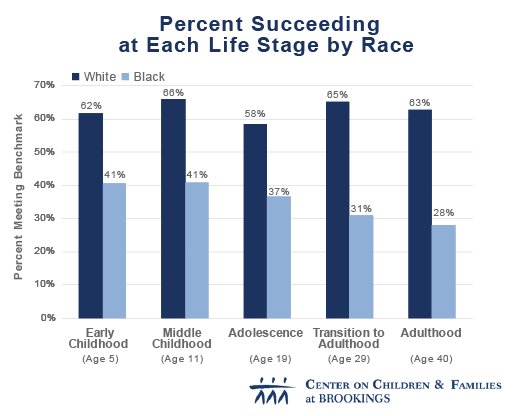

My colleague Isabel Sawhill has adopted a simple, single metric for upward mobility: making it to the middle class by middle age. Almost two in three whites clear this hurdle, compared to just three out of ten blacks:

Note: Updated figures based on Figure 4 from “Pathways to the Middle Class,”

Sawhill, Winship, and Grannis (2012)

The Sawhill graph also shows measures of success for each preceding life stage. For example, success at adolescence requires graduating high school with a GPA of at least 2.5, without either getting pregnant or being arrested:

The black-white gap widens with each successive life stage, showing the cumulative effects of disadvantage – and the need to address the racial mobility gap at each and every critical moment.

Forty years ago, King’s dream was for blacks to achieve true equality with whites. The other American Dream is for every individual to have a fair chance of success. Now, they are the same dream: a nation of real opportunity for every child, of every color. We still have a long way to march.

Commentary

The Other American Dream: Social Mobility, Race and Opportunity

August 28, 2013