Nearly ten years ago, the collapse of the sub-prime mortgage market sent the U.S. economy into a tailspin. As housing prices dropped and unemployment climbed, vulnerable households found themselves unable to refinance the mortgages they borrowed under better economic circumstances. Struggling to meet ever-increasing monthly payments, more and more homeowners defaulted on their mortgages.

After the crisis, Congress and financial regulators increased regulation of the credit risk associated with mortgage lending, including the enforcement of stronger underwriting standards. But according to new research published in the Spring 2018 edition of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, a boom in nonbank mortgage lending means the mortgage market is still exposed to liquidity risk that very few people are talking about.

The paper, by You Suk Kim, Steven M. Laufer, and Karen M. Pence of the Federal Reserve Board and Richard Stanton and Nancy E. Wallace of the University of California at Berkeley, argues that liquidity risk associated with the nonbank mortgage sector was also a key driver of the crisis—and those same vulnerabilities are not only still present, but pose an even greater risk to the system today because the nonbank sector is an even larger part of the market.

Nonbank mortgage originators and servicers—i.e. independent mortgage companies that are not subsidiaries of a bank or a bank holding company—are subject to far greater liquidity risks but are less regulated than bank-lenders and servicers. As of 2016, non-bank financial institutions originated close to 50 percent of all mortgages and 75 percent of mortgages with explicit government backing.

The authors find that risks are particularly acute for mortgages in securitizations guaranteed by Ginnie Mae. The servicing contract for these loans places substantial financial responsibility on the servicers, yet the limited data available suggest that the nonbanks that concentrate on servicing these loans have less ability to withstand liquidity strains.

The research also suggests that mortgages originated by nonbanks are of lower credit quality than those originated by banks, making nonbank lenders more vulnerable to delinquencies triggered by a fall in house prices through the higher costs of servicing delinquent loans. A larger fraction of nonbank originations are insured by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) or Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), which tend to be more likely to default than other types. Among mortgages in Ginnie Mae pools, the data indicate that mortgages originated by nonbanks are twice as likely as bank-originated mortgages to be two or more months delinquent.

The authors warn that in the event of a crisis, nonbanks have limited resources to draw upon and the government would probably bear the majority of increased credit and operational losses. Further, failure of these nonbanks could result in a considerable contraction in mortgage credit availability, especially for lower-income and minority borrowers, who are more likely to receive mortgages from nonbank lenders.

One way to help homeowners in the event of a crisis? Redesign the mortgage market

Another new paper, from Columbia University’s Tomasz Piskorski and Stanford University’s Amit Seru, considers several proposals for redesigning the market to provide more effective debt relief to homeowners in times of crisis. These proposals include relying mechanisms and policies that are put in place before the crisis, as well as post-crisis debt relief policies.

One of the proposals they consider would automatically index mortgage payments to local economic conditions. Under this proposal, mortgages wouldn’t operate under a rigid contract that sets a fixed or variable rate. Instead, payments would automatically adjust as local economic conditions change. Because such a system would circumvent financial intermediaries, homeowners could see much faster debt relief during economic downturns.

The authors stress the challenges policymakers would face in designing policies that are in place before the crisis, particularly because economic conditions that interact with the housing market vary greatly across the country and change over time. These conditions include obvious factors such as unemployment and house prices, but also factors related to the details of mortgage contracts and the ability and capacity of financial intermediaries to provide debt relief.

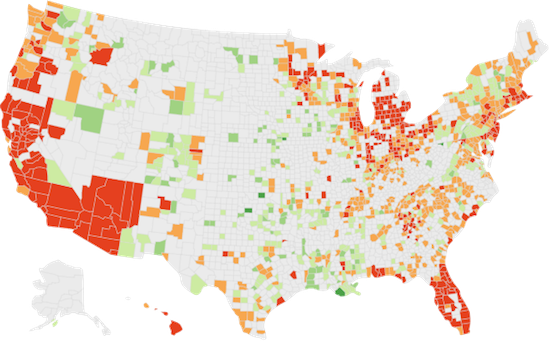

To illustrate that point, this map shows changes in unemployment and house prices during the Great Recession. Areas in red would likely see the biggest benefits from an automatically indexed mortgage system.

After evaluating several proposals and data, the authors conclude that there is no single “bullet-proof” solution. For instance, national-level policies—for example monetary policy tools—are likely to be too blunt. Housing and labor market downturns affect different parts of the country to such varying degree, and not all areas need the same amount of stimulus at the same time.

The authors stress the importance of using local rather than national economic conditions as a benchmark for mortgage contracts or debt relief polices since these are more likely to capture the variability of housing market at the local level. It makes sense, they argue, to reduce mortgage payments more in the areas where local unemployment rises and house price growth is negative.

Finally, while mechanisms and policies that are put in place before the crisis, such as indexed mortgage contracts, allow for quick debt relief, their implementation would require that policymakers have a solid understanding of the market’s underlying risk structure and how it relates to the new indices before a crisis occurs. Because errors in precisely predicting how markets evolve are likely, policymakers may have to also rely on post-crisis debt relief solutions, for example the Home Affordable Refinancing Program (HARP) and the Home Affordable Modification Program (HAMP) created by the Obama administration during the last housing crisis. Such policies can be designed and implemented post-crisis, and as a result they circumvent the problem of precise prediction of risk structure in local markets. However, these also come with the possible cost of delaying debt relief and reducing its effectiveness due to the various political and financial intermediary constraints.

To learn more about new research published in the Spring 2018 edition of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, visit the full project page or read summaries of all six new papers here.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The mortgage market risk no one’s talking about, plus a proposal to redesign the system

March 8, 2018