More than 45 million Turkish citizens, recording an impressive 86.56 percent participation rate, cast their votes at the highly anticipated and bitterly—at times even violently—contested Turkish parliamentary elections on Sunday. The election came with high stakes, namely whether Turkey would remain a parliamentary democracy or become a presidential regime with fewer separation of powers, as desired by current president and former prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

For the first time in over a decade, the governing AK Party had some meaningful competition in the election. The two main opposition parties, the Republican People’s Party (CHP) and the National Action Party (MHP), received 25 and 16 percent of the vote respectively. The AK Party still came in well ahead of its opposition with just under 41 percent of the vote, but the decline in its support from the last election means it will not be celebrating the results as a great victory.

Erdoğan had one ambition for this election: for the AK Party to gain the minimum 330 parliamentary seats required to call a referendum on establishing a presidential regime. But with only 258 seats, the AK Party did not even reach the 276 seats required to form a government, and may now find itself forming a coalition with MHP.

The main credit for blocking the path that would have further formalized Erdoğan’s one-man autocratic rule goes to Turkey’s pro-Kurdish party, the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP). Under Selahattin Demirtas’ leadership, HDP, against considerable odds, broke through Turkey’s notoriously high 10 percent threshold for entering parliament. They took 13 percent of the votes and will receive 79 seats in parliament.

This is all good news for everyone, except, of course, Erdoğan. Here are 5 reasons why:

1. Confidence in “free and fair” elections

Turkey’s current constitution requires the president to remain politically neutral especially when the country is going through parliamentary elections. Erdoğan, nevertheless, openly ran electoral rallies in support of the AK Party using state resources, showed (to put it in mildly) bad sportsmanship against opposition parties and engaged in polarizing rhetoric leading up to the election. Along with questions on fairness, there were also deep concerns about the increased risk of electoral fraud. In anticipation of such problems, Turkish civil society organizations mobilized to protect the inviolability of the ballot box. Thankfully not only did HDP cross the threshold, but there were also no serious problems reported from polling stations or from the vote counting process. This is a promising sign that Turkish democracy may still be alive and well.

2. A parliament with diverse, but also liberal voices

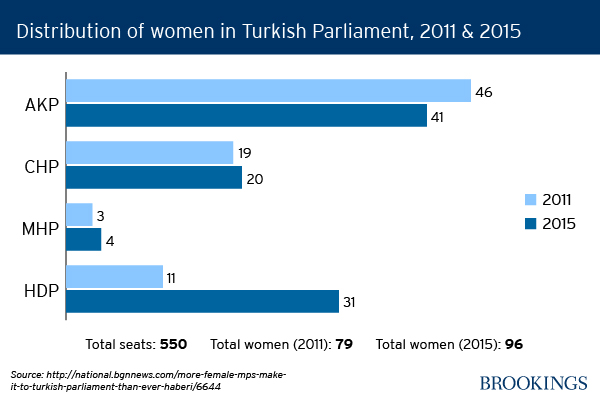

The HDP is known to have a progressive, inclusive and liberal agenda that values minorities’ and women’s rights. While lacking sufficient numbers to effectively shape outcomes, HDP now has the power (especially in coalition with their more liberal CHP counterpart) to call for reforms and measures that can improve some of Erdoğan’s more regressive policies.

3. Increased Accountability

The new parliamentary composition is likely to allow for closer scrutiny of corruption allegations and budgetary issues. Gone are the days of building palaces that are bigger than the Palace of Versailles, with 1,150 rooms and a cost of more than $600 million, just to solve a cockroach problem.

4. Reoriented Foreign Policy

The post-election seat distribution can more energetically reflect the displeasure recorded in public opinion polls and is likely to bring some significant foreign policy changes. The Turkish public fears that involvement in Syria and the AK Party’s confrontational policies towards Egypt and Israel will worsen the chaos in the region, and lead to a loss of markets for Turkish goods. Public opinion polls already show greater support for cooperation with EU and NATO in addressing international challenges.

The new, more diverse structure of the parliament may very well succeed in readjusting Turkey’s foreign policy away from its emphasis on the Middle East back to its traditional Western vocation. Kadri Gursel, a prominent Turkish columnist, argues that there may be a return to the “factory settings” of Turkish foreign policy. These include institutionalism; predictability; secular foreign policy and peaceful and good relations with Turkey’s neighbors.

5. Fresh hopes for Turkish democracy – but with a caveat

Turkey’s democracy has been under immense strain since AK Party won the 2011 parliamentary elections with almost 50 percent of the vote. That marked the moment when Erdoğan, then as prime minister, started to drift away from the economic and political reforms that had earned Turkey great international prestige. It was also the time when the international community started questioning Turkey’s Western character and Erdoğan came to be seen as increasingly illiberal or even authoritarian. These questions intensified after Erdoğan became the first popularly elected president of Turkey in August 2014, and broadened his utter disregard for media freedoms and for judicial and regulatory independence. Turkey’s future did not look very bright when Erdoğan began using polarizing language and offering conspiracy theories implicating the West in response to faltering economic growth and corruption scandals.

The result of this election is a game-changer, but it is still merely a first step. Turkey’s democratic institutions have suffered greatly over the last few years and it would be unrealistic to expect miracles just from HDP’s success. Huge challenges still await Turkish democracy. Reconstructing the independence of state institutions, repairing the damage inflicted to liberal democracy and winning the trust and confidence of investors, direly needed for boosting economic growth, will not be an easy exercise. There is only so much that the HDP and the other two opposition parties can do beyond raising their voices and mobilizing pressure on the government.

Don’t rush the celebrations

A lot still depends on the AK Party and on its next steps. It is possible that the AK Party will form a coalition government and the most likely pairing will be with the ultranationalist MHP. This could paint a completely different political picture marked by political instability, further distancing from the West, and a stalemate on the Kurdish peace negotiations, if not renewed fighting with Kurdish rebels.

The best outcome is that the AK Party will take a critical look at itself, learn the key lessons from the results of the elections and return to their policies from the days when they truly enjoyed broad popular support and widespread international acclaim. On the other hand, Turkey will find itself in increasing difficulty if the old habits of the AK Party prove hard to change.

Commentary

The Kurdish rescue of Turkish democracy

June 7, 2015