Last week, the House of Representatives passed the Build Back Better Act, which boasts an array of social and climate programs, ranging from generous support for child care, paid leave, and new health benefits to renewable electricity tax credits.

Democrats are trumpeting the vote as a major milestone, although the bill’s passage is only a waystation en route to a tougher showdown in the Senate.

Yet beneath the bill’s main events resides something else important: an impressive collection of “place-based” programs targeted at helping particular places and their residents thrive, rather than helping people more generally wherever they live. Tucked into the $2.2 trillion bill are numerous place-based programs aimed at combating the nation’s epidemic of uneven development, with spatially targeted funding that would promote a more equitable distribution of economic growth across the country.

Some of the pending place-oriented programs would boost the nation’s regional innovation capacity by investing hundreds of millions of dollars in regional tech hubs, manufacturing institutes, and regional industry clusters. Others would provide block grants so distressed labor markets can expand employment opportunities. And still others would channel multiyear investments into communities to help with energy and industrial transitions, community revitalization, and rural partnerships.

An initial count finds more than 30 place-centric programs in the legislation that would fund translational research at universities; bolster supply-chain resilience around ports; accelerate the deployment of low- and zero-emissions technologies; promote rural prosperity, establish incubator spaces for Main Street small businesses in underserved communities, and provide funding for Indigenous communities. Add it all up and these items—mostly unheralded in media coverage of the package but major in the history of U.S. place-based policy—represent a genuine breakthrough for the growing recognition that smart investments aimed at strengthening the economies of particular regions or localities can enhance overall welfare and prosperity.

For much of the postwar 20th century and into the 2000s, federal policy discussions looked askance at place-based policy while minimizing the problems it aimed to address. During the early postwar period, market forces reduced job, wage, investment, and business formation disparities between regions and (to some extent) neighborhoods; for example, as the South began to catch up economically with the rest of the country.

Given that, the economic and policy mainstream felt it could trust what it believed was the self-regulating and benign nature of the market’s impacts across different places and communities. Consequently, Washington, D.C. and economic elites remained skeptical of ideas that would counter the nation’s spatial divides, belaboring the mixed record of early place-based interventions that directed resources toward particular geographic areas.

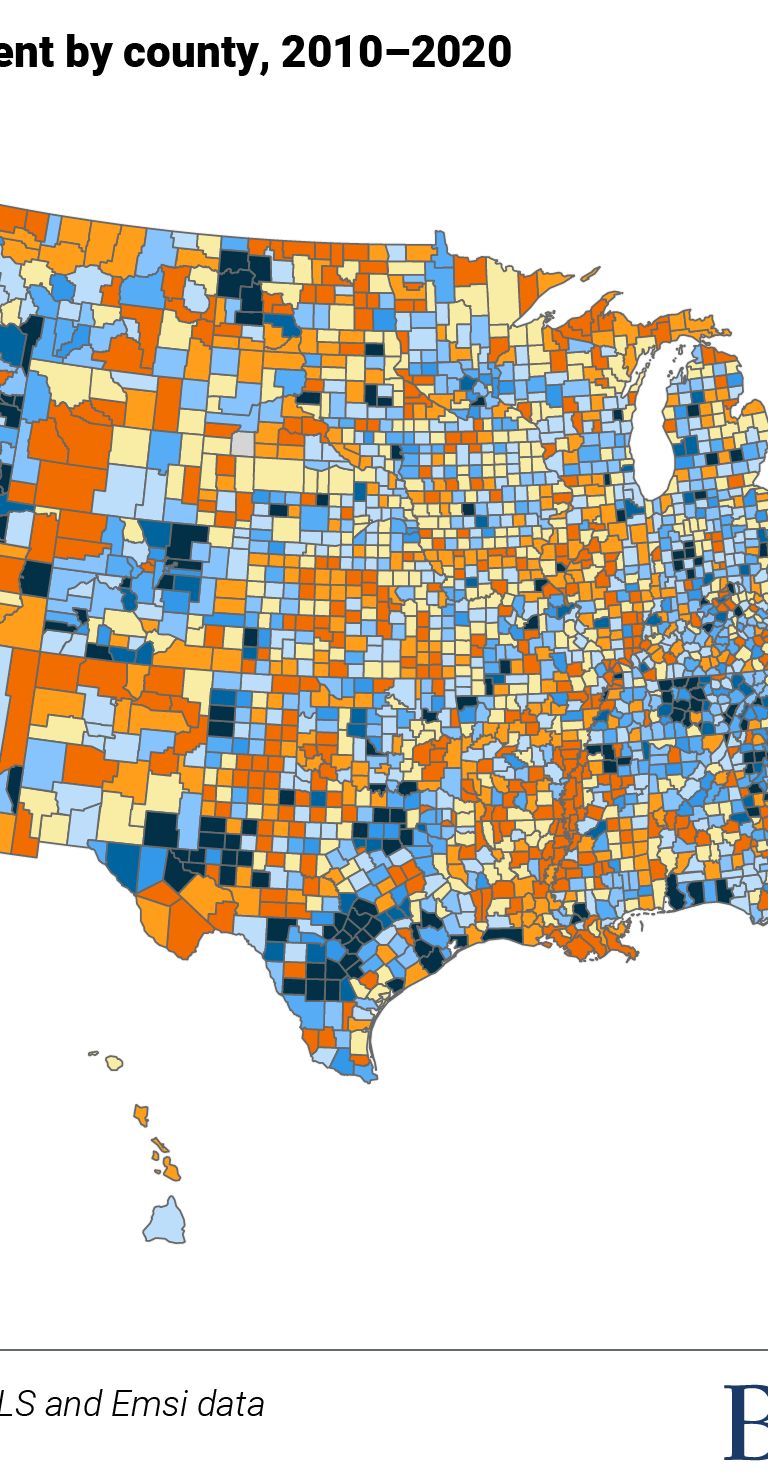

Yet even as policymakers maintained their faith in the self-regulation of the market, it was no longer operating in the way they talked about it. Since the 1980s, and with intensified force in the last decade, regional and neighborhood fortunes have ceased converging and have been sharply diverging, with disastrous impacts on thousands of urban and rural communities.

The results of the 2016 election underscored the nation’s geographic crisis and prompted a surge of place-oriented research from scholars at Brookings, including Brookings Metro, the Hamilton Project, and the Center for Sustainable Development, as well as scholars at other research organizations such as the Economic Innovation Group, Harvard University, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, the Aspen Institute, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, among many others.

That welcome burst of attention, paired with advances in the theory and practice of place-based economic development, has led to a broad reassessment of the gravity of the nation’s geographical divides, the need to respond, and the possibility of success. Reflecting that, the Build Back Better Act represents the most significant American embrace of place-based ideas since the Great Society—or maybe even the New Deal. In short, if the act is passed, it will launch a major new period of place-focused investment and local problem-solving.

Of course, success is not guaranteed. To begin with, the House bill’s place-based and related prosperity provisions must survive a tough gauntlet in the coming weeks. That’s because the House bill now heads to the Senate, where getting to “yes” might require paring back various provisions—although one would think the place-based elements would be especially pertinent to states like West Virginia and Arizona, home to the bill’s main Democratic critics, Sens. Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema.

Beyond that, the new place-based policies will face numerous implementation challenges. Depleted federal agencies will need to renew their proficiency at program design and rulemaking to ensure any new place-based proposals are well crafted and user-friendly. Smart rulemaking and design detail will be particularly important given the mixed record of some earlier place-based efforts.

Potentially even more challenging will be getting resources to the highly distressed and underserved communities that need them the most. Such targeting is a key point of many place-based initiatives, yet many of the most appropriate recipients of place-based investment possess limited capacity to package their ideas and navigate the requirements of federal programs. Federal agencies will need to be creative and energetic in providing upfront support for community program applicants and watch that program criteria do not create inadvertent barriers for the worst-off places.

And then there is the need to show results quickly, amid both the current political atmosphere and a legacy of skepticism for place-based policies. Given those factors, it will be important for the federal government and local stakeholders to get success measures from the outset, manage the fact that place-based development takes time (several years at a minimum), and work hard to deliver excellent outcomes and communicate them widely.

With all of that said, the Build Back Better Act as passed by the House must be counted as a major advance for national policy that acknowledges regional and neighborhood decline and seeks to counter it with a new generation of place-based responses.

Addressing regional inequality will absolutely require the kind of universal social programs that compose the bulk of the Build Back Better Act. Such broad welfare programs represent an important revival of the federal government acting as a “pro-active force for uniting disparate regions into one national economy,” as notes the sociologist Robert Manduca. Yet in addition to such universal investment, a true push to ameliorate the nation’s stark geographic divides can and should reinvestigate the power of targeted, place-oriented policies to reverse local distress and catalyze growth. The House version of the Build Back Better Act represents a major watershed for that work. Let’s hope the Senate embraces it too.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The House’s Build Back Better Act is a milestone for place-based solutions

November 23, 2021