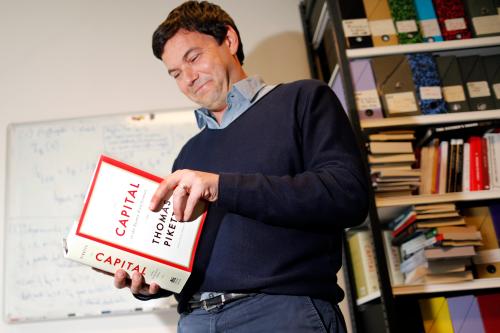

Thomas Piketty’s book Capital in the Twenty-First Century has captured the world’s attention, putting the relationship between capital accumulation and inequality at the center of economic debate. What makes Piketty’s argument so special is his insistence on a fundamental trend stemming from the very nature of capitalist growth. It is an argument much in the tradition of the great economists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In an age of tweets, his bestseller falls just short of a thousand pages.

The book’s release follows more than a decade of painstaking research by Piketty and others, including Oxford University’s Tony Atkinson. There were minor problems with the treatment of the massive data set, particularly the measurement of capital incomes in the United Kingdom. But the long-term trends identified – a rise in capital owners’ share of income and the concentration of “primary income” (before taxes and transfers) at the very top of the distribution in the United States and other major economies – remain unchallenged.

The law of diminishing returns leads one to expect the return on each additional unit of capital to decline. A key to Piketty’s results is that in recent decades the return to capital has diminished, if at all, proportionately much less than the rate at which capital has been growing, thereby leading to an increasing share of capital income.

Within the framework of textbook microeconomic theory, this happens when the “elasticity of substitution” in the production function is greater than one: capital can be substituted for labor, imperfectly, but with a small enough decline in the rate of return so that the share of capital increases with greater capital intensity. Larry Summers recently argued that in a dynamic context, the evidence for elasticity of substitution greater than one is weak if one measures the return net of depreciation, because depreciation increases proportionately with the growth of the capital stock.

But traditional elasticity of substitution measures the ease of substitution with a given state of technical knowledge. If there is technical change that saves on labor, the result over time looks similar to what high elasticity of substitution would produce. In fact, just a few months ago, Summers himself proposed a reformulation of the production function that distinguished between traditional capital (K1), which remains, to some degree, a complement to labor (L), and a new kind of capital (K2), which would be a perfect substitute for L.

An increase in K2 would lead to increases in output, the rate of return to K1, and capital’s share of total income. At the same time, increasing the amount of “effective labor” – that is, K2 + L – would push wages down. This would be true even if the elasticity of substitution between K1 and aggregate effective labor were less than one.

Until recently not much capital could be classified as K2, with machines that could substitute for labor doing so far from perfectly. But, with the rise of “intelligent” machines and software, K2’s share of total capital is growing. Oxford University’s Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne estimate that such machines eventually could perform roughly 47% of existing jobs in the US.

If that is true, the aggregate share of capital is bound to increase. Given that capital ownership remains concentrated among those with high incomes, the share of income going to the very top of the distribution also will rise. The tendency of these capital owners to save a large proportion of their income – and, in many cases, not to have a large number of children – would augment wealth concentration further.

Other factors could help to augment inequality further. One that has been largely neglected in the debate about Piketty’s book is the tendency of the superrich to marry one another – an increasingly common phenomenon as more women join the group of high earners. This, too, causes income concentration to occur faster than it did two or three decades ago, when wealthy men married women less likely to have comparably large incomes. Add to that the modern scale effects on professional and “superstar” incomes – a result of winner-take-all global markets – and a picture emerges of fundamental forces tending to concentrate primary income at the top.

Without potent policies aimed at counteracting these trends, inequality will almost certainly continue to rise in the coming years. Restoring some balance to the income distribution and encouraging social mobility, while strengthening incentives for innovation and growth, will be among the most important – and formidable – challenges of the twenty-first century.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edThe Great Income Divide

July 21, 2014