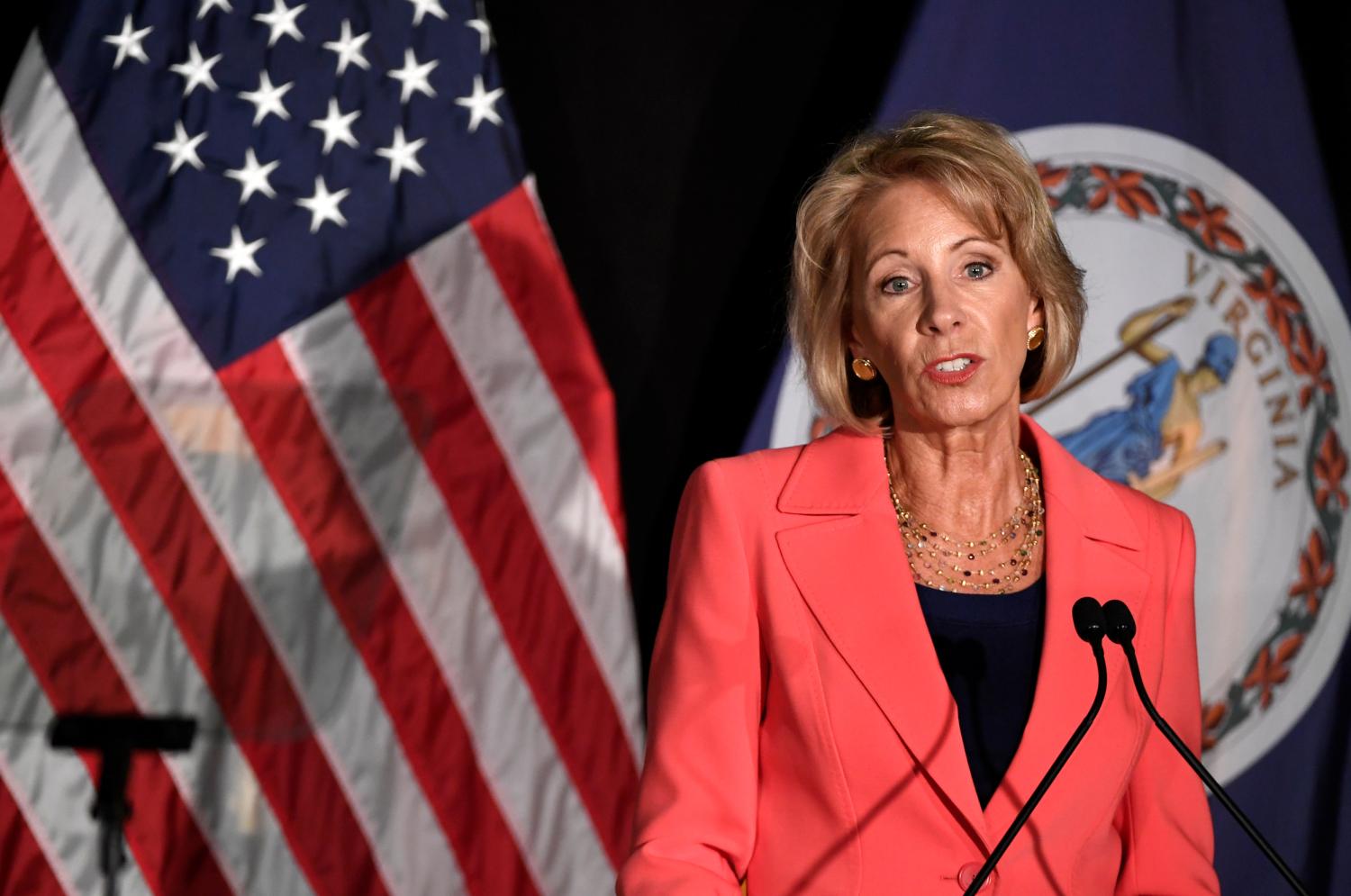

In November of last year, the U.S. Department of Education released its long-awaited proposed regulations on sexual harassment. More than a year earlier, Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos had withdrawn the Obama administration’s controversial Title IX guidelines and promised to develop a fairer, more effective alternative. Criticizing her predecessors’ reliance on unilaterally announced “Dear Colleague Letters,” DeVos announced that the “era of rule by letters is over.” From now on, she vowed, the department would use the notice-and-comment rulemaking process mandated by the Administrative Procedure Act.

After meeting with interest groups and engaging in negotiations with other agencies, the department published a 150-page document that laid out its initial position and invited comment on a variety of issues. The government shutdown forced the agency to extend the original Jan. 28 deadline for submitting comments until Jan. 30, but it could be further delayed as well. Given the thousands of comments already submitted, it will take many months for the department to analyze the response and consider modifications. Meanwhile, Democrats in the House have promised to take “bold, immediate action” to prevent the new rules from going into effect. The department’s final rules will inevitably be challenged in court. In other words, we are in for another long debate over sexual harassment regulations.

The proposal has received praise from civil libertarians who had warned that the Obama rules threatened due process and freedom of speech. But many Democrats in Congress expressed outrage. According to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, “With wanton disregard, this Administration has cruelly codified their utter contempt for survivor justice by making schools unwelcoming and less safe.” Rep. Jackie Speier called Secretary DeVos “a shill for [the] Trump Admin’s slash & burn agenda to gut protections for sexual violence survivors.” Sen. Patty Murray accused the administration of “sweeping the scourge of sexual assault under the rug, weakening protections for students and survivors, and allowing colleges and universities to shirk their responsibility to keep students safe.”

Democrats in the House have promised to take “bold, immediate action” to prevent the new rules from going into effect. The department’s final rules will inevitably be challenged in court. In other words, we are in for another long debate over sexual harassment regulations.

Democrats’ criticism focused on two features of the proposed rules: the requirements that schools hold live disciplinary proceedings on sexual misconduct allegations; and that they allow cross-examination of both accusers and the accused. The Department of Education claims that these are essential elements of fair procedures. Its critics insist that this would make victims of sexual harassment less likely to come forward.

These procedural mandates are just one part of the changes wrought by the proposal. Just as importantly, they change the definition of sexual harassment covered by Title IX, limit the number of school officials responsible for reporting allegations, curtail schools’ responsibility for addressing off-campus misconduct, and distinguish between rules that apply to colleges and those that apply to elementary and secondary schools. Equally significant is what the proposal does not say. The Obama-era guidelines included detailed requirements on training for faculty, staff, and students, and on remedial measures addressed to both specific victims and “the broader student population.” The proposal, in contrast, describes in general terms the accommodations schools must provide to students who have been subjected to harassment, but says little about training or comprehensive remedies.

Since Betsy DeVos is arguably the most unpopular member of the Trump Cabinet and the president himself has repeatedly demeaned women and even boasted about committing sexual assault, Democrats have little reason to trust the current administration on this issue. The problem they face is that simply preventing the proposed regulations from going into effect will do little to move Title IX regulation in the direction they favor. Because the Obama-era guidelines and enforcement policy are no longer in effect, executive branch inaction would throw the issue back to the courts, which have not been particularly sympathetic to the position taken by women’s advocacy groups and their political allies. Consequently, the Education Department’s critics have no choice but to delve into the details of the multitude of issues raised in the proposal.

Dueling paradigms

The proposal differs from the Obama-era guidelines not just on a few specifics, but in its fundamental framework. The Department of Education explained that a primary “purpose of this regulatory action” is “to better align the Department’s regulations with the text and purpose of Title IX and Supreme Court precedent and other case law.” It described the two leading Supreme Court interpretations of Title IX—Gebser v. Largo Vista Independent School District (1998) and Davis v. Monroe City Board of Education (1999)—as “foundational,” emphasizing that it had been “persuaded by the policy rationales relied on” by the court. The Obama administration, in contrast, considered the remedial framework established in Gebser and Davis inadequate for addressing what it repeatedly described as an “epidemic” of sexual assault on college campuses. In 2011 and 2014, the department adopted what then-Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights Russlyn Ali called a “new paradigm” for addressing sexual assault on campus—a parallel set of administrative mandates that were far more demanding than the liability rules enforced by the courts.

The key difference between these two approaches is the level of responsibility imposed on educational institutions. According to the Supreme Court and the November proposal, schools are responsible for responding promptly and effectively to allegations of sexual misconduct of which they have “actual knowledge.” The focus is on processing individual complaints: Schools must institute an adequate grievance procedure, fairly investigate the complaints they receive, punish the guilty, and provide reasonable accommodations to those whose education has been limited by the harassment. What is “adequate,” “fair,” and “reasonable” is left up to school officials.

The guidelines issued by the Obama administration, in contrast, required schools to adopt comprehensive measures to “end any harassment, eliminate a hostile environment if it has been created, and prevent harassment from occurring again.” These extensive regulatory requirements were based on the contention that sexual harassment is not the product of a few identifiable perpetrators, but of a “rape culture” that has subjected one in every five college students to sexual assault. Since schools have tolerated this culture for years, they cannot be trusted to take the dramatic steps needed to change it.

This battle has been fought in administrative and judicial forums because Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 itself says nothing about sexual harassment. It only prohibits sex discrimination by educational institutions that receive federal funds. For nearly a quarter century, federal administrators left the issue to the courts. Federal judges held that harassment constitutes sex discrimination under Title IX and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act if it is aimed at members of a particular sex.

They then confronted the question of when educational institutions should be held responsible for the conduct of faculty, staff, and students. To what extent should school officials be expected to monitor and control the behavior of thousands of people, an undertaking made especially difficult by the fact that much of the activity in question takes place in private? Lacking any guidance from Congress, judges turned to tort and employment law, which seemed to provide familiar liability rules. Lower courts disagreed about when schools should be held liable for misconduct by their teachers and students. Some ruled that schools were liable if they “knew or should have known” about behavior that created a “hostile environment.” Others held that schools would be held responsible only if they had “actual knowledge” of specific incidents and failed to take corrective action.

When the Supreme Court finally addressed the issue in 1998-99, it settled on a relatively lenient standard. Schools could not be held liable for money damages unless a school official who “has authority to institute corrective action” has “actual notice of, and is deliberately indifferent to” the misconduct. To violate Title IX, Justice O’Connor wrote in her majority opinion in Davis, this misconduct must be “so severe, pervasive and objectively offensive that it effectively bars the victim’s access to an educational opportunity or benefit.” Judges, she warned, “should refrain from second-guessing the disciplinary decisions made by school administrators.”

These Supreme Court rulings received harsh criticism from women’s groups and in the law reviews. They warned that this standard gives schools strong incentives to “stick their head in the sand” (as one law review author put it) by discouraging students from filing complaints. The Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) agreed. Just one day before the 2001 inauguration of George W. Bush, OCR announced that it would not follow the Supreme Court’s interpretation of schools’ liability under Title IX. The court’s formulation, it insisted, applied only to court suits for money damages, not to administrative rules on what schools must do to qualify for federal funds.

For the next eight years, the Bush administration did little either to explain or to enforce these guidelines. Indeed, it was hard to see how the Department of Education could ever hope to enforce them. Never in the history of Title IX had it invoked the funding cut-off. Instead it had relied on court action to give the act its enforcement teeth. The break with the courts took that option off the table. Consequently, the significance of the department’s rejection of the Supreme Court’s liability standard did not become evident until 2010, when the White House, the Department of Education, and the Department of Justice launched its high-profile effort to address the problem of sexual assault on campus, using the threat of lengthy, reputation-damaging investigations as its principal enforcement tool.

The liability framework developed by the courts was based on two key assumptions, both of which were challenged by feminist legal scholars, by the new “survivor” groups springing up on campuses nationwide, and, eventually, by the Obama administration. The first is that the central problem is a few “bad apples,” usually male, who must be identified, punished, and possibly banished from the institution. The second is that the threat of damage suits will give the educational institutions sufficiently strong incentives to discover misconduct, compensate victims, and punish perpetrators.

Critics contended that focusing on solely on complaints filed by aggrieved students overlooks the larger problem of “rape culture” and institutional complicity in it. This critique was most forcefully articulated by Catherine MacKinnon, the feminist legal theorist who played the most prominent role in establishing sexual harassment as a form of sex discrimination. In her book, “Sexual Harassment of Working Women,” she charged that the liability framework “fails to capture the broadly social sexuality/employment nexus that comprises the injury of sexual harassment.” Because it treats “the incidents as if they were outrages particular to an individual woman rather than integral to her social status as a woman worker, the personal approach on the legal level fails to analyze the relevant dimensions of the problem.” In short, this approach “considers individual and compensable something which is fundamentally social and should be eliminated.”

Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights Ali sounded similar themes when she explained that the objective of OCR’s “new paradigm” was to “change the culture on the college campus,” which is “hugely important if we are to cure the epidemic of sexual violence on college campuses across the country.” According to a 2014 report issued by the White House Council on Women and Girls, “Sexual assault is pervasive because our culture still allows it to persist. According to the experts, violence prevention can’t just focus on the perpetrators and the survivors. It has to involve everyone.” Consequently, effective prevention programs must be “sustained (not brief, one-shot educational programs), comprehensive, and address the root individual, relational and societal causes of sexual assault.” The mere threat of litigation would never be enough to achieve the necessary “sea-change” in attitudes. It would take sustained, aggressive action by federal administrators.

From paradigms to particulars

Almost all the regulatory changes proposed by the Department of Education in 2018 flowed from its rejection of the Obama administration’s post-2010 “new paradigm.” This is evident in the proposal’s definition of sexual harassment covered by Title IX: “unwelcome conduct on the basis of sex that is so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it effectively denies a person equal access to the recipient’s educational program or activity.” This comes directly from Gebser and Davis. The department emphasized that “Title IX does not prohibit sex-based misconduct that does not rise to that level of severity.”

Almost all the regulatory changes proposed by the Department of Education in 2018 flowed from its rejection of the Obama administration’s post-2010 “new paradigm.”

In its 2011 Dear Colleague Letter, in contrast, OCR had defined sexual harassment as any “unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature,” including “verbal conduct” such as “making sexual comments, jokes, or gestures,” “spreading sexual rumors,” and “creating e-mails or Web sites of a sexual nature.” When the University of Montana incorporated the Supreme Court’s definition into its sexual harassment policy, the Obama OCR objected, insisting that the university establish policies to “encourage students to report sexual harassment early, before such conduct becomes severe or pervasive, so that it can take steps to prevent the harassment from creating a hostile environment.” That was consistent with the goal of changing student culture. But such a sweeping definition also raised troubling free speech concerns. The high bar set by the November proposal permits (but does not require) schools to dial back its monitoring of student speech and conduct.

Similarly, the proposal holds schools responsible only for harassment that takes place within its educational “program or activity” and perpetrated by a person “under the school’s disciplinary authority.” OCR’s 2014 guidance, in contrast, required schools to “process all complaints of sexual violence, regardless of where the conduct occurred, to determine whether the conduct … had continuing effects on campus.” Schools must address these “continuing effects” by taking “steps to provide appropriate remedies for the complainant, and, where appropriate, the broader school population.” In other words, schools must provide adequate remedies for sexual harassment even if they had no way to prevent it.

Perhaps the most important feature of the November proposal is the emphasis it places on the formal complaints. To prevent schools from taking a “see no evil, hear no evil” approach to the problem, it requires all schools to establish a clear, well-publicized grievance procedure. The 2011/2014 guidelines had required this as well. The difference is that the previous guidelines also required schools to investigate allegations reported by “responsible employees,” “regardless of whether the student, student’s parents, or a third party files a formal complaint.” According to the earlier guidelines, “responsible employees”—a category that included anyone “whom a student could reasonably believe” has the “authority or duty” to take action to redress sexual violence—must report to the Title IX coordinator “all relevant details about the alleged sexual violence that a student or other person has shared.” In other words, all faculty members, most resident assistants, and many other school officials have a duty to report possible misconduct even if the target of the misconduct objects. The rationale was that addressing a social problem this serious should not depend on individual students’ willingness to come forward.

The proposal, in contrast, imposes no such responsibility on school employees: In most circumstances, schools have “actual knowledge” of misconduct only when a student files a formal complaint with the Title IX coordinator. At that point, the school has a duty to institute a full investigation. The proposal also gives students the option of reporting misconduct without filing a “formal complaint that would initiate a grievance process.” It maintained “that often the most effective measures a recipient [school] can take to support its students in the aftermath of alleged incidents of sexual harassment are outside the grievance process and involve working with the affected individuals to provide reasonable supportive measures that increase the likelihood that they will be able to continue their education in a safe, supportive environment.” Such measures can include counseling, extension of deadlines, modification of class schedules, campus escort services, and “mutual restrictions on contact between the parties.” Giving students the option of receiving supportive services without initiating an investigation, the department claims, gives complainants “greater control over the process” and recognizes “that college and university students are generally adults capable of deciding whether supportive measures alone suffice to protect their educational access.” Here again, the emphasis is on responding to particular individuals, not attempting to provide comprehensive solutions to the large social problem.

The proposal also followed the Supreme Court’s admonition against second-guessing school officials. It explained that the Department of Education will not find that a school acted with “deliberate indifference” “merely because the Assistant Secretary would have reached a different determination based on an independent weighing of the evidence.” OCR will “not conduct a de novo review of the recipient’s investigation.” The Obama administration, in contrast, had not only established detailed requirements for investigations and supportive services, but had demanded that schools make all their case files available to OCR so it could evaluate the adequacy of their response.

The Obama administration’s guidelines on how schools must handle complaints were based on the assumption that since most infractions go unreported, schools must take aggressive steps to bring them to light and to deal harshly with known cases. To combat the epidemic of sexual assault, schools must convince more victims to come forward, which requires relaxing due process protections developed in less dangerous times. To this end OCR insisted that schools use the lenient “preponderance of the evidence” (“more likely than not”) standard of evidence. It discouraged schools from allowing cross-examination of accusers. It encouraged them to adopt a “single investigator” model that dispensed with disciplinary boards and hearings altogether, giving a single person appointed by the Title IX coordinator authority not just to collect evidence and interrogate witnesses, but also to determine guilt and innocence.

By returning focus to the particular individuals involved in the grievance process, the proposal elevates the importance of traditional understandings of due process. It noted that just as severe sexual harassment can limit a student’s educational opportunity, but so too can a student be “unjustifiably separated from his or her education on the basis of sex, in violation of title IX” if a school does not follow “fair procedures before imposing discipline.” Given the important stakes for both the accuser and the accused and the extent to which the outcome of many grievance procedures depends on the credibility of witnesses, it maintained, there is no substitute for live hearings with the opportunity for cross-examination. Quoting a Supreme Court opinion, it describes cross-examination as “the greatest legal engine ever invented for the discovery of truth.” Just as importantly, the proposal prohibits schools from using the “single investigator model” because “fundamental fairness to both parties” requires that the investigation of a complaint and the “ultimate decision about responsibility should not be left in the hands of a single person.” On these procedural matters, the main theme of the proposal is that the accuser and the accused should be placed on equal footing, with no presumption that one side or the other be given the benefit of the doubt. To suggest that female accusers should always be believed, it implied, is to engage in the very sort of sexual stereotyping Title IX prohibits.

Attention should also be paid to what the proposal does not say. OCR’s 2014 guidance devoted two single-spaced pages to list remedies “for the broader student population.” These include “offering counseling, health, mental health and comprehensive victim services to all students affected by sexual harassment or sexual violence”; adding discussion of sexual harassment policies to student orientations; and “conducting periodic assessments of student activities to ensure that the practices and behavior of students do not violate the school’s policy against sexual harassment and violence.” Most of these measures were included in the detailed agreements OCR negotiated with hundreds of colleges. Those guidelines and settlements also mandated annual training for virtually everyone on campus.

The November proposal says almost nothing on these topics. It provides a brief description of the “supportive measures” offered to individual students who have reported sexual misconduct, but omits any reference to services “for the broader student population.” Training is similarly left to the discretion of school officials.

How will schools respond?

One might expect colleges and universities to welcome this relaxation of federal regulation. But that overlooks key features of their situation. Most importantly, many schools have already instituted the changes demanded or recommended by the Obama administration. This means they have internal compliance offices strongly committed to combatting all forms of sexual harassment on campus. Moreover, few college presidents or deans wish to be accused of backsliding on this issue. On all the matters discussed above—with the important exception of disciplinary procedures—schools remain free to go beyond the federally established minimums. We should not expect most schools to narrow their definition of harassment, to reduce training and mandatory reporting, or to curtail the services they offer to those who have experienced various forms of harassment.

One might expect colleges and universities to welcome this relaxation of federal regulation. But that overlooks key features of their situation.

The proposed rules would, though, require many schools to change their procedures for investigating and resolving complaints. If a school refuses to hold live hearings or to allow cross-examination, what can the Department of Education do? It can threaten to withhold federal funding, but will never follow through. As usual, enforcement will come through the courts, this time in the form of suits brought by students claiming they were denied due process in disciplinary proceedings. There have already been about 200 such suits, and schools have lost a significant number of them. When the Obama-era guidelines were in effect, schools facing due process challenges could argue that they had followed administrative recommendations, and that judges should defer to the expertise of the department. If the proposed regulations become final, the deference argument will work in the opposite direction. Faced with a greater litigational threat, schools might change their rules. This will precipitate major battles on many campuses.

Of course, it is important to remember that at this point we are only dealing with a proposal. The Department of Education has asked for additional guidance on a number of issues, and is likely to amend or clarify its rules in response to comments. For example, it might be able to articulate additional limits on cross-examination that would make live hearings less stressful for accusers without reducing the opportunity for judging the credibility of witnesses. Critics should take advantage of the opportunities presented by the notice-and-comment rulemaking process. But in doing so they must recognize that the Department of Education is unlikely to retreat from its embrace of the Gebser/Davis framework, however distasteful its critics might find that choice.

Shep Melnick is Tip O’Neill Professor of American Politics at Boston College and author of “The Transformation of Title IX: Regulating Gender Equality in Education” (Brookings, 2018).

Correction 1/25/19: This post previously stated that the comment period for the Department of Education’s proposed regulations on sexual harassment had been delayed indefinitely. It has been extended to Jan. 30, 2019, and the post has been updated to reflect that.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).