Among the many items on the agenda for Congress and the White House this fall is how to fund many of the federal government’s key programs—including defense, education, science research, and foreign aid—and whether a government shutdown can be averted in the process. There are many ways the two sides might resolve the issues at play but first, let’s review how we got here.

Certainly, a series of distinct choices made by Congress and the president have played a part. In 2011, as part of the deal to increase the debt ceiling, Congress passed, and the president signed, the Budget Control Act (BCA), which included caps on discretionary spending between 2012 and 2021. The BCA also created the so-called congressional “Supercommittee,” which was supposed to produce a plan for reducing the deficit by $1.5 trillion over ten years. If it failed to do so (and spoiler alert, it did), the BCA’s discretionary spending limits would get even more restrictive.

In December 2013, led by Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI) and Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA), Congress used savings from military and federal civilian retirement, education, and transportation programs to effectively increase the BCA’s spending caps for two years, 2014 and 2015. (Technically, this was accomplished by offsetting part of the additional, more restrictive limits that took effect after the Supercommittee failed, and not by increasing the BCA’s underlying caps.) As of October 1, however, the 2011 law’s original restrictions will return—and should Congress and the president choose to exceed those caps, many discretionary programs will be subject to an across-the-board cut, better known as the sequester.

In the face of the return of this more restrictive budget environment, President Obama and congressional Democrats have taken a hard line on the limits on non-defense discretionary spending. Senate Democrats have pledged to obstruct, and Obama has promised to veto, all appropriations measures until a broader deal that allows for more generous spending on things like education, housing, energy assistance, and science research is reached. Some congressional Republicans, meanwhile, have vowed to oppose even a short-term continuing resolution that would provide more time for deal-making unless that bill reflects key priorities, including eliminating any federal funding for Planned Parenthood.

Journalists have characterized this negotiating situation as “epic” and “explosive,” but this sort of late-stage, multi-bill deal-making should feel somewhat familiar. As research by Peter Hanson (summarized nicely here) has documented, a full 39 percent of all appropriations bills between 1975 and 2012 were handled either as part of an omnibus package or a year-long continuing resolution. According to the Congressional Research Service, moreover, delayed action on appropriations has plagued Presidents Bush and Obama alike; since 2001, only 11 of 182 appropriations bills were enacted by the start of the new fiscal year, and only 47 were passed as standalone bills.

Not only have we been here before, but research by Jonathan Woon and Sarah Anderson suggests this year’s conditions are ripe for this kind of delay. Both ideological division across institutions (between the president and congressional majorities) and within Congress itself (between the majority party’s appropriators and the average member of the majority party in each chamber), they argue, draw out the process. Under their argument, as ideological distances increase, the actors involved are more willing to sacrifice other legislative activities in favor of a longer appropriations process.

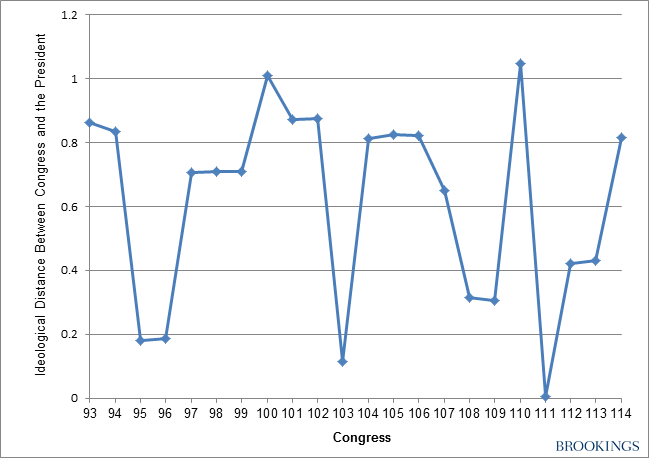

How does the current Congress stack up on these measures? The first graph below plots Woon and Anderson’s measure of ideological distance between Congress and the president over time. Thanks to Republicans regaining the majority in the Senate last fall, Congress and the president are farther apart on this measure than at any previous point in the Obama administration. And except for the two years at the end of the Bush 43 administration when the Democrats controlled Congress, Congress and the president haven’t been this far apart since the end of the Clinton administration.

Following Woon and Anderson, distance here is measured using Common Space DW-NOMINATE scores, available from voteview.com. The distance presented is the absolute distance between the president’s score and the midpoint between the median score for the majority party in the House and the majority party in the Senate.

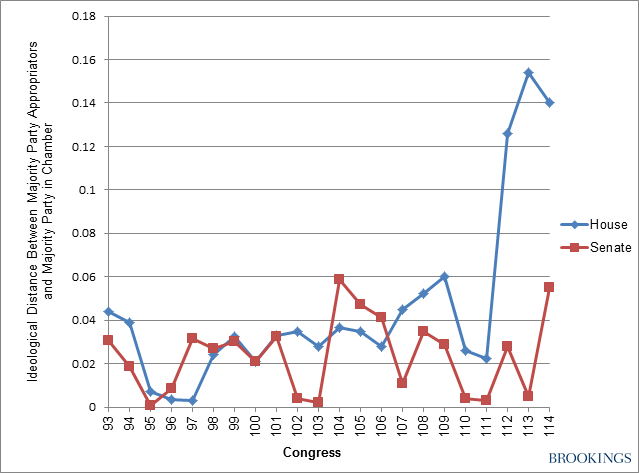

It’s not just disagreement between Congress and the president that is likely contributing to delayed appropriating this year, however. The graph below uses similar data to compare the majority party members of each house’s appropriations committee to the majority party’s membership in the chamber as a whole.

The graph shows the absolute distance between the Common Space DW-NOMINATE score for the median member of each chamber’s majority party and the median member of the majority party’s contingent on the corresponding chamber’s appropriations committee.

Here, we see again that the 114th Congress is also plagued by internal divisions between House and Senate appropriators and the other members of their parties that are likely slowing down the appropriations process. Indeed, even the chair of the House Appropriations panel, Rep. Hal Rogers (R-KY), has lamented the disconnect between his preferred approach and that of his caucus.

Within this partisan and ideological context, finally, institutional rules and norms haven’t helped Congress’s efforts to move appropriations measures in a timely fashion. In July, House Speaker John Boehner pulled the Interior-Environment appropriations bill from floor consideration. The House had adopted two Democratic-sponsored amendments that would have limited the display of the Confederate flag on federal lands, but under pressure from southern members of his caucus, the bill’s Republican floor manager, Rep. Ken Calvert (R-CA), offered an amendment relaxing those new restrictions. So angry were Democrats about the move that Boehner eventually pulled all appropriations measures from floor consideration out of concern that they would attach amendments related to the flag to every single spending bill.

Given the power of the House majority leadership to control debate in the chamber via the Rules Committee, how did this conflict arise? Unlike most other measures, appropriations bills are still reliably open to amendment in the House. Since 1995, 77 percent of the regular appropriations bills have been considered under some type of open amending process, and to date, the only measures considered under any kind of open rules in the House this year were appropriations bills.

Given this precedent for more open debate, the House majority party can find itself calling new parliamentary moves on the fly if they want to keep the process moving. In 2009, for example, the Democratic House leadership, concerned about the 100-plus amendments filed by minority party Republicans, changed tactics midstream to exert more control over the debate on the appropriations bill for the Commerce, Justice, and State Departments. While Boehner could have pursued such a strategy back in July, doing so would have meant violating a key pledge made after he assumed leadership of the chamber.

Congress and the president may have driven their negotiating bus to the brink of a cliff again this fall, but a range of institutional factors that have paved the road—and will certainly affect any deal they manage to reach.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The budget showdown: How did we get here?

September 14, 2015