Kids performing poorly on cognitive tests at age five are likely to do fine as adults, so long as they are from an affluent or better-educated family. At least that’s true in the UK, according to a new report discussed on our blog yesterday.

Why? The key factors seem to be parental education, getting better at math by 10, “soft skills,” attending good K-12 schools, and getting a college degree.

Fair or unfair?

So: fair or unfair? It is worth saying at the outset that even the age of five is quite late to be trying to capture skills. Huge gaps open up in both cognitive and non-cognitive skills even in the first months and years of life.

If a parent works hard to help their infant become more skilled, this is unambiguously fantastic news. The fact that more affluent parents are more willing or able to do so simply means we have to work harder to help ensure poorer kids do not fall behind. Otherwise the parenting gap becomes an opportunity gap. But if some children end up with more skills as a result of their excellent choice of parents, we should expect the labor market to reward them appropriately.

The question is how far the differential development of skills can be seen as resulting from meritocratic or non-meritocratic processes. Private schools provide a useful case in point.

Private schools: another support beam for the glass floor

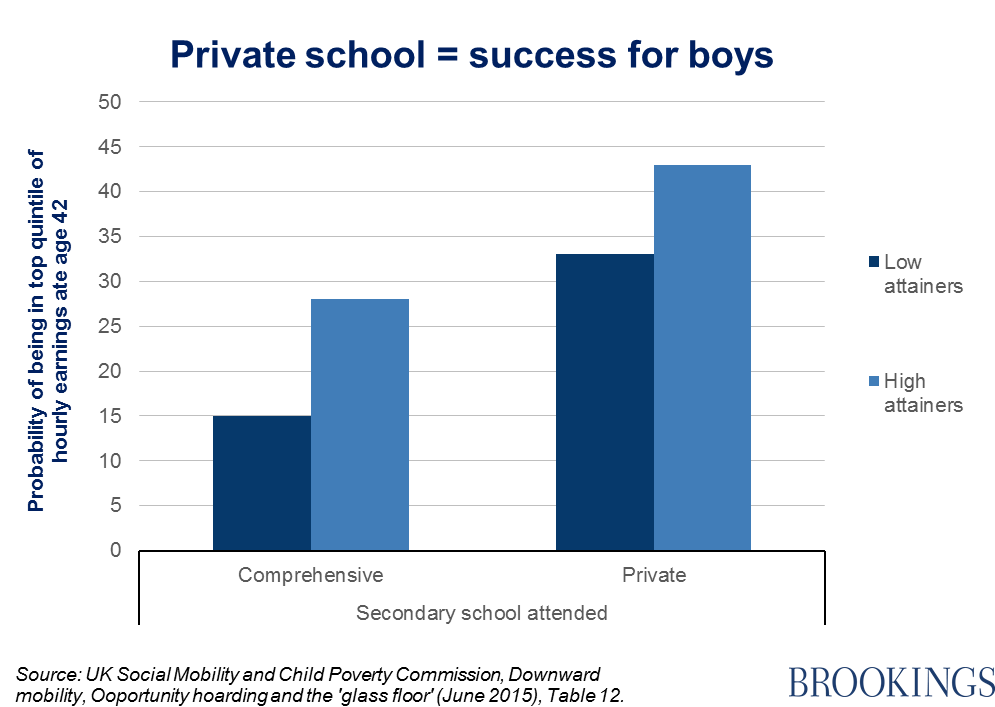

One strong finding from the UK paper, authored by Abigail McKnight from the London School of Economics, is that attendance at a private school for grades K-12 helps initially less-able kids to make it to the top. In fact, boys who were low-scorers (in the bottom 40 percent) at the age of five but went to a fee-paying school were more likely to become a high earner (top quintile) than a high-scoring five year old who attended a comprehensive school (translation to U.S. audience: local high school):

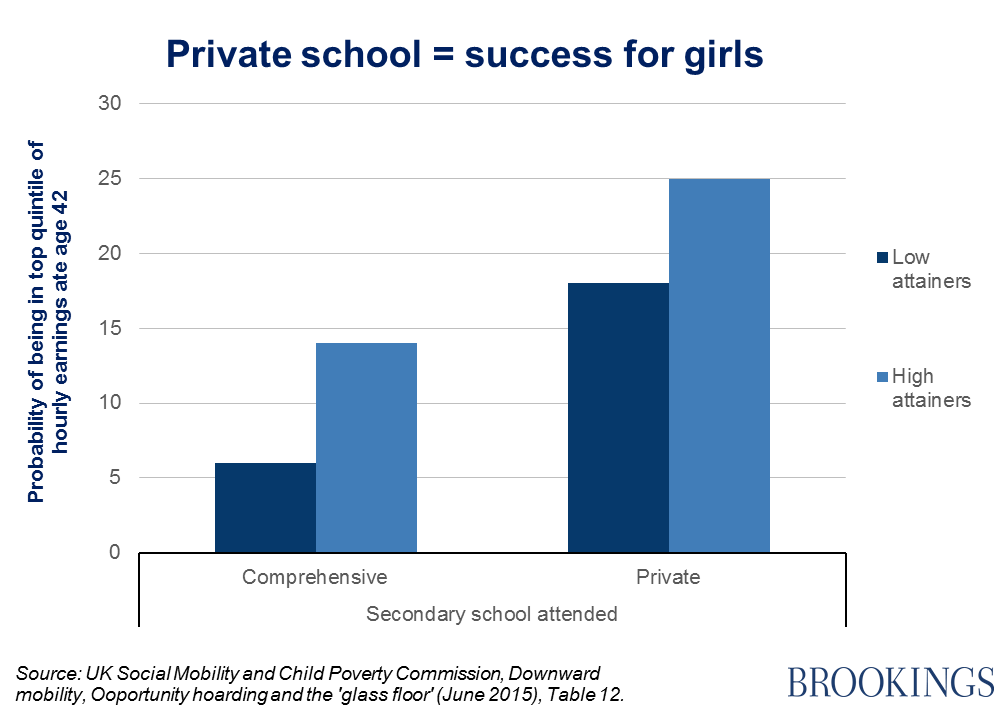

The same pattern holds for girls, although at much reduced overall levels, since women were much less likely to become high earners than men:

Skills or connections?

Why do 18-year-olds coming out of private schools do better? There are two obvious explanations: first, they have acquired a higher level of characteristics or knowledge that adds value in the labor market; second, they have developed a social network or reputational advantage that is unrelated to actual ability.

Connections play some part, of course, but it is hard to imagine they are the largest. The harder truth is that the kids who may not display high skills at the age of five have developed higher skills by the time they hit the world of work. This is because of the efforts of parents; the advantages and comforts that affluence brings, through the selection of good schools and teachers; the support and provision of extra-curricular learning opportunities; and so on.

The tough question is at what point the virtuous efforts of parents morph into opportunity hoarding – hogging the top spots through illegitimate means such as exclusionary zoning laws, college alumni preferences, or informal allocation of unpaid internships, to name a few candidates. Individual incentives, like doing everything possible for our own children, may come into conflict with collective goods, in this case the maintenance of a meritocratic market and a fair society.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The British glass floor, part 2

July 14, 2015