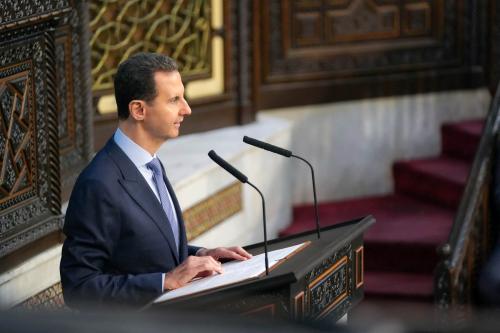

On December 8, 2024, armed rebels took the Syrian city of Damascus, forcing long-time ruler President Bashar al-Assad to flee the country. The move comes after 13 years of civil war and brings the iron-clad rule of the Assad regime effectively to a close. Below, Brookings experts break down what this all means, what happens now, and the questions that remain.

Syria’s jubilation resonates with Iraqis

Of all people, Iraqis understand the jubilation of Syrians today at the toppling of the brutal and decades-long Assad dictatorship. Similar scenes, though with the backdrop of occupation, played out across Iraq over two decades ago when another brutal Baathist dictator, Saddam Hussein, was deposed. At the same time, Iraqis are cautious of what may happen next, as the face of the armed Syrian opposition today is a man who had engaged in terrorism in Iraq as a member of al-Qaida and, later, the Islamic State. Iraq’s Shia armed groups who had once helped prop up Bashar al-Assad, at the behest of Iran, have now abandoned him, and the Iraqi government has withdrawn its diplomats from their embassy in Damascus and turned its focus inwards, seeking to preserve internal stability.

While many analysts have used Iraq as only a cautionary tale for Syria’s future, that argument both infantilizes Syrians and ignores the positive lessons that Iraq can impart. Both countries were under the thumb of Baathism for decades, suffered external interventions, and have diverse populations. For one, Syria can learn from Iraq’s successful Kurdistan region model, which has granted Iraqi Kurds a large degree of autonomy and recognized their language and culture and their integral role in the federal government. Iraq, too, has warnings: to not ignore transitional justice, to not rush the writing of the new constitution, and to not employ extreme and punitive de-Baathification.

Winners and losers in Syria

The unexpected collapse of one of the most brutal dictatorships in the Middle East has been celebrated by millions of Syrians inside and outside the country—and for a good reason. The Baathist regime which ruled Syria continuously since 1963, with the last five decades under the particular brand of Assad family despotism, has not only exhausted Syria but also turned it into a Russian garrison and launchpad for Iran’s regional ambitions.

Bashar al-Assad’s defeat is also the strategic defeat of Russia and Iran in the Levant.

It is also a setback for Gulf Arab monarchies that had been trying to normalize the Assad regime. They stand to lose political influence, as Turkey, a longtime backer of the Syrian rebels, stands to gain.

But for Syrians, the hard work starts now. The opposition forces inside and outside the country have some experience in governance, but they do not know how to govern in harmony with one another.

Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the leading force in the lightning offensive, has been ruling over the northern border province of Idlib, where more than 3 million Syrians live under a conservative regime. It is an effective fighting force but with jihadist roots and al-Qaida baggage. HTS cannot dominate the diverse political and sociological tapestry of Syrian society—and luckily its leader, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, seems to understand that.

The U.S.-allied Kurds and Turkey-backed Sunni Arabs are the other militia groups that have helped Assad’s downfall and have also been running their separate enclaves in northern Syria, but they now need to show political and ideological flexibility to be part of an inclusive interim governance project in Damascus. Curbing the influence of Islamists will not be easy, but their inclusion in the political process and the specter of elections within a year, as well as Ankara’s influence, could have a moderating impact.

In the end, Syria will not be worse than what it was. Millions of Syrians now have a chance to return home and provide a balance against armed militia groups and radicalism. The West will continue to have an interest in Syria, not only in fighting an Islamic State resurgence but also in staying engaged to guarantee Israel’s security, ward off extremism, and help the country’s evolution.

Syria will affect Russia's position in Africa, too

Like Iran, Russia suffered a tremendous loss of power projection capacity as a result of the Assad regime falling to Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). Russia’s limited air strikes didn’t halt the HTS offensive, and Russian advisors and military assets proved useless. The blows are to Russia’s strategic posture, logistical capabilities, and credibility across the Middle East and Africa.

At stake for Russia are its Hemeimeem air base and its Tartus naval base, the core bases of its military footprint in the Middle East. As Russia’s only refueling place in the Mediterranean Sea, Tartus is important for Russian military and smuggling operations around the world and an irritant on NATO’s southern flank.

Russian bases in Syria have been critical for supplying Russia’s Africa Corps across Africa. While Russia also has bases in Libya to supply Africa Corps, its logistical systems would be constrained if the Syrian bases were lost. Having softened its tone, Moscow is reaching out to HTS to negotiate preserving its access to the bases. While HTS may be eager to court international legitimation (watching Moscow’s closeness with the Taliban), would it risk the presence of Russia’s military assets to turn against its rule down the road?

Regardless of whether Russia will ultimately be able to keep the Syrian bases or not, Russia is left with egg on its face: The juntas it supports in West Africa and the regimes it courts in Central Africa and on the Atlantic Coast have just witnessed how impotent Russia actually is in the moment of truth. These credibility losses compound the tactical losses Africa Corps suffered from local jihadists and rebels in Mali over the summer. Dependent on Africa Corps’ praetorian guard services, the juntas in West Africa can’t just drop their alliances with Russia. But the glitz is starting to peel off.

Hopefully, the Trump administration will not completely relegate Africa to the management of Middle Eastern strongmen and will build on Russia’s exposed weaknesses to push back its aggressive, expansionist, and anti-America agenda, which is also detrimental to local populations, the rule of law, and democracy. Just like in Syria and the Middle East, the United States retains extensive and multifaceted interests in Africa and should seek to shape developments there even without extensive military deployments.

Dusting off a blueprint for a Syrian-led transition

In August 2011, President Barack Obama called on Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to “step aside.” In February 2012, then-Ambassador to the U.N. Susan Rice said that Assad’s “days are numbered.” Over 13 years and hundreds of thousands of lives later, the serial killer and crime boss who presided over Syria’s destruction is finally gone, probably looting the Central Bank on his way out.

Assad’s flight at last unlocks the opportunity outlined in Geneva in June 2012 for a “transitional governing body exercising full executive powers” in Syria. Kofi Annan, then the United Nations and League of Arab States (LAS) joint special envoy for Syria, chaired an action group including the foreign ministers of the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Russia, China, Turkey, Iraq, Kuwait, and Qatar, as well as the European Union foreign policy chief and the secretaries-general of the U.N. and LAS. The action group’s final communique outlined principles and guidelines for a Syrian-led transition that Assad thwarted with barrel bombs and torture. In December 2015, the U.N. Security Council again endorsed the 2012 Geneva communique, in Resolution 2254.

So, the blueprint for transition already exists. The United Nations secretary-general and his special envoy for Syria should jettison the moribund Geneva-based Syrian constitutional process work and pivot immediately to Damascus to activate the Geneva communique and Resolution 2254. Turkey and others with connections to those apparently in control in Damascus can help. The urgent task is to establish a transitional governing body in which those that might otherwise splinter into fighting factions have a stake. For if Syria now falls into chaos, outsiders near and far will undoubtedly hyper-charge the battles on behalf of favored groups—as we have seen in recent years in Sudan, Yemen, Libya, and Ethiopia.

Damascus calls itself the “beating heart” (“قلب نابض”) of the Arab world, but Assad turned Syria into the bleeding heart. In light of Tunisia’s democratic backsliding, Syria has the potential to become the belated success of the so-called Arab Spring, after a nightmarish 13 years. Admittedly, it’s a long shot, but it’s worth trying to unite Syrians and those present with Annan in Geneva around the 2012 principles and guidelines as the first line of defense against Syria’s current acute fractionalization from propelling the country toward more violence and chaos.

Why Assad’s army collapsed—and what it may mean for Syria’s future

A dominant explanation for how Bashar al-Assad had managed to survive since 2011 had been the cohesion of his military and security forces—particularly, an officer corps stacked with a minority group (the Alawis) that viewed regime change as an existential threat. Why then, did this military seem to not even put up a fight in the past week?

A number of hypotheses carry some weight, including exhaustion, conscript morale, a lack of resolve on Assad’s part, and the shock and awe of the rebel’s momentum. However, I would call attention to two broader factors as well: first, the lack of support from Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah might have demoralized the Syrian military into giving up, and second, the rebels’ promises of amnesty and autonomy might have led the Alawis to see a future for themselves post-Assad.

Looking ahead, I will be watching two dynamics. First, domestically, the early steps Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) makes will greatly influence whether Syria relapses into civil war. Thus far, HTS is sending the right signals: promising equal rights to all Syrians, decentralization and regional autonomy, and amnesty for Assad’s soldiers. Yet, if any one of Syria’s many armed groups begins to feel aggrieved, you can expect a return to violence.

Second, Assad’s overthrow may carry significant reverberations for other conflicts in the region. The inability or unwillingness of Russia and Iran to come to Assad’s aid weakens the hand of Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis in Yemen, and the Shia militias in Iraq, potentially shifting power dynamics in each of these contexts.

U.S. support for a post-Assad transition in Syria

With the stunning news that Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad has been overthrown and fled to Moscow, attention is now focused on the political transition that has just gotten underway. While the painful legacies of five decades of brutal rule under the Assads will not soon be forgotten, Syrians are now looking to the future. How the coming transition unfolds is a matter for Syrians alone to determine. Yet it is not too soon for the United States to offer support, not only to aid a society emerging from decades of repression but to reduce the odds of chaos in the months ahead and increase the chances that Syria’s next government will be more inclusive, just, and stable.

Engagement with post-Assad Syria will fall largely to the incoming Trump administration, which will likely prioritize the withdrawal of the remaining 900 U.S. troops stationed in the country’s northeast. Trump has also made clear his intent to stay out of Syria’s conflict, writing on Truth Social that it is not America’s fight. But as conflict gives way to transition, there are steps the United States could take that are far removed from military intervention but consequential in helping a new Syria find its footing.

One big step seems already to be in play: the Biden administration is reportedly reconsidering the designation of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham as a terrorist organization. Other positive, low-cost measures a Trump administration could take include the lifting of economic sanctions to increase inflows of money that would ease the suffering of millions of Syrians. The United States could also lend its expertise to assist in recovering assets looted by Assad and his cronies, estimated to be in the billions of dollars. Further, helping Syrians hold accountable those responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity—whether by the regime or the opposition—will be crucial for the social healing that needs to happen if Syrians are to recover from decades of trauma and violence. Finally, providing support for reconstruction efforts—something the United States appropriately avoided given the Assad regime’s track record of stealing humanitarian and other assistance—could help jump-start Syrian efforts to rebuild a country still ravaged by 13 years of war.

Whether a Trump administration sees Syria’s conflict as a matter of U.S. interest, a political transition that fails and descends into renewed violence, displacement, and regional spillover would be difficult for the United States to ignore. Contributing in these modest ways to a Syrian-led, Syrian-designed political process—ideally modeled along the lines of the transition blueprint detailed in U.N. Security Council resolution 2254 of 2015—would offer tangible help to Syrians, address pressing near-term challenges, and, in the process, increase the odds that the transition in Damascus will succeed.

Designing a new Syria is step one

The stunning fall of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad represents the latest example of how 2024 is the most transformative year in the Middle East since 1979. The region has been upended in umpteen ways amidst conflicts with a dizzying array of actors. Honing in on Syria, a wide variety of groups has desired the end of the Assad regime since Hafez al-Assad ruled the country. With those aspirations finally realized this weekend as more than 50 years of Assad rule came to a spectacular close, one looming question now is how domestic power-sharing can be knit together in an equitable manner that precludes unhelpful meddling by external actors and provides governance and security to the Syrian people. While this is indeed a tall order, smaller steps towards making it reality can come in the form of beginning to implement United Nations Security Council Resolution 2254 such as drafting a new constitution and preparing to hold elections.

One year after the Syrian uprising began, I testified before Congress that the United States does not want Assad in power, does not want a power vacuum, and does not want continued violence. The first has finally been achieved after 13 long years; the second and third will only come about through the establishment of a stable, secure state that can faithfully represent its citizens. “Revolutions are the only political events which confront us directly and inevitably with the problem of beginning,” according to Hannah Arendt, which is to say that the birth of a new Syria will invariably be painful, frustrating, and represent exactly that: an opportunity for a new beginning.

Return of refugees: A pyrrhic victory for Turkey?

There are many reasons for Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to feel jubilant about the collapse of the Assad regime and the arrival of the opposition led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham to the seat of government in Damascus. One such reason is the prospect of Syrian refugees returning home en masse at a time when public resentment is persistently virulent and at times violent.

Erdoğan and Ahmet Davutoğlu, then his minister of foreign affairs, had enthusiastically adopted an open-door policy for the refugees because they were convinced that the Assad regime would collapse within just a few months if not weeks. For the duo, this was an opportunity to show to the world Turkey’s largesse while European countries were closing doors to refugees as well as to win the hearts and minds of the refugees and eventually the new regime. An effective public relations campaign centered around the duty to protect fellow Muslims facing persecution, drawing parallels to the migration experience (Hijrah) of the Prophet Mohammed and his followers from Mecca to Medina, helped win over public support. Thus, Turkey became the country with the largest number of refugees globally as their numbers peaked at 3.7 million.

In the absence of effective, durable solutions in the form of voluntary return, resettlement, or local integration, Syrians found themselves in a protracted situation in Turkey just as the public mood became increasingly resentful and hostile. This mood and the opposition’s politicization of the refugee issue during the presidential and municipal elections coupled with an ever-worsening economic situation led Erdoğan to promise and embark on a “voluntary, safe, and dignified” return policy (see page 13). The policy faced criticisms from human and refugee rights advocates but helped the government to showcase the falling numbers of refugees in Turkey. The opposition’s victory in Syria doubtless will strengthen the pace of this trend and benefit Erdoğan’s popularity. Yet, this popularity risks being a pyrrhic one if sustainable peace and economic reconstruction in Syria fails to materialize, precipitating new rounds of displacement back to Turkey.

History warns against triumphalism

The fall of the Assad regime deals yet another blow to Iran’s Islamic Republic and its strategy for extending its influence across the Middle East as a means of countering its foremost adversaries, the United States and Israel. Together with recent Israeli military actions in Lebanon and Iran, Iranian leaders are facing historic setbacks to costly and hard-fought improvements in the Shia theocracy’s position in the Arab world. The explanation lies in Tehran’s reliance on asymmetric warfare through a network of militias that its leadership cultivated, coordinated, trained, and supplied with advanced weaponry but ultimately couldn’t protect. What enabled Iran’s rise is now paving the way for its fall.

The loss of Damascus represents a calamitous breach in the conduit for resupplying Hezbollah, the jewel in the crown of Iran’s proxy network, whose leadership and sophisticated arsenal have been decimated by Israel over the past few months. That was Syria’s primary value to Tehran, and what persuaded Iranian leaders to intervene to preserve Bashar al-Assad after Syrians went to the streets in 2011. The Islamic Republic can draw on its history of rebounding from severe strategic reversals by playing the long game, but without access to Syria, even Iran’s enterprising Revolutionary Guard Corps will be hard-pressed to rebuild Hezbollah, or Hamas for that matter, quickly.

History warns against triumphalism: the Islamic Republic has risen from the ashes before, notably in the late 1980s after the end of the long-stalemated war with Iraq and a precarious leadership transition. And nothing matters more to the current leadership than regime survival. But given their perennial sense of insecurity, Iranian leaders are profoundly cognizant of risks inherent in their current situation—they are powerless to prevent the attrition and decapitation of their proxies; their own defenses are damaged and exposed; and they are now blindsided by the collapse of an ally. They know their own citizens dream of opening the doors to the theocracy’s dungeons just as Syrians are doing today. Tehran may respond by upping the ante, especially on the nuclear program, as a hedge against Iran’s own vulnerability and as a ploy to exploit President-elect Donald Trump’s musings about a deal with Iran.

The struggle for Syria enters round two

In 1965, the British journalist Patrick Seale published his classic book “The Struggle for Syria.” Seale argued that the weak, fragmented Syrian state served as the arena in which regional and international actors fought directly and by proxy for regional hegemony. In 1949 alone, three coups d’etat took place in Syria. Syria found refuge by merging with Egypt into the United Arab Republic, but it broke away in 1961 and resumed its precarious independent existence. It was only in 1971 that Hafez al-Assad established a coherent, powerful state. Assad offered his people a Faustian deal of stability and an important regional position in return for a tyrannical and corrupt regime dominated by members of the Alawite minority.

Assad died in 2000 and was succeeded by his son Bashar. Bashar had a mixed record during his first 11 years in power, but he failed abysmally in dealing with the Syrian version of the Arab Spring which developed into a brutal civil war. Assad was saved by Russian and Iranian military intervention in 2015, but his regime and Syria did not recover from the war. Syria became an Iranian proxy, an important link in Tehran’s “axis of resistance” against Israel. Assad’s and his regime’s fall are major blows to Iran’s position in the region and to its efforts to shore up its most important proxy, Hezbollah.

It is still unclear how Syria’s domestic politics will develop in the coming weeks and months, but it is clear that several external actors are trying to shape Syria’s politics, and that the outcome of their respective efforts will have a major influence on the regional politics of the Middle East. Turkey played a major role in encouraging Abu Mohammed al-Jolani and his Hayat Tahrir al-Sham to launch their initial offensive. Turkey is worried about Syria’s Kurdish minority and wants at least part of the Syrian refugees to return to Syria. Iran’s Sunni rivals will seek to exploit its initial defeat and reduce if not eliminate its position in Syria. Israel is primarily interested in preventing radical groups from establishing themselves in the Syrian Golan, but it is also interested in having an orderly government in Syria and in eliminating Iran’s presence and influence. Russia wants to keep its two naval and one aerial bases.

And what about the United States? There is a unique opportunity to weaken Iran and build the pro-Western coalition that President Joe Biden has been seeking. But his administration is on its way out and President-elect Donald Trump has posted on social media that the United States should have “nothing to do” with the Syrian “mess.” During his first term, several of his aides persuaded him not to recall the small but crucial U.S. military force stationed in eastern Syria. It is key that his advisors make yet another effort to persuade him that Washington lead and win the current struggle for Syria.

A revolution in Middle Eastern geopolitics

The Assad dynasty’s fall after a half-century of repression and tyranny is a revolution in the geopolitics of the Middle East. Syria has been Iran’s closest ally since the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and the most reliable base for Russian military operations for decades. Tehran and Moscow are for now big losers in the changes in Damascus.

The speed of the collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s regime was unexpected by virtually all observers. I have been working on Syria since 1977: I watched the Assads survive the Hama uprising, family disputes with Rifaat Assad (Hafez’s brother and Bashar’s uncle), endless crisis in Lebanon, and 13 years of civil war. They seemed firmly in charge.

Syria was a volatile and unstable country for years before Hafez seized power in 1970. Coups were common. A critical question now: can the rebels stabilize the country or will Syria become a power vacuum? Instability in Syria will bleed over into Lebanon and possibly Jordan. The hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees are another potential source of unrest if they come home and add to the burden of an already weak economy and labor market.

The Assads made the Golan Heights Israel’s quietest border between the 1974 Syrian-Israeli disengagement agreement and the 2011 Syrian civil war. That is unlikely to remain the case given the armed rebels’ ideological determination to regain the leadership of fighting Israel (the putative leader of the revolution highlights the Golan in his nom de guerre, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani).

The United States and Syria have generally been adversaries for the last 50 years, although President Bill Clinton came within yards of securing a Syrian-Israeli peace treaty in 2000. We now have 900 boots on the ground in Syria. Our allies, including Israel, Jordan, and Turkey, have vital interests at stake; they will look for leadership from Washington.

Much is uncertain and potentially dangerous in the wake of the stunning events of the last fortnight. For now, however, we should enjoy the joy of the Syrian people free of a despotic dynasty.

Assad’s fall exposes regional fault lines

For millions of Syrians, the fall of Bashar al-Assad is a moment of jubilation. Yet it will bring back to the fore deep fault lines that threaten further regional intervention in Syria.

Iran was closely aligned with Assad, its longest-standing Arab ally. But some of Iran’s regional foes were wary of a Syrian opposition that included extreme Islamists. Israel opted to sit on the fence in the war at its doorstep. Much of the Sunni Gulf remained conflicted in its support for popular (and largely Sunni) opposition to Assad, and more recently led the effort to normalize relations with the Assad regime, when it seemed like his victory was secure. The more Islamist-friendly Turkey, on the other hand, backed the opposition more actively. Hamas, which had ties to Iran in the years leading up to 2011, demurred for a time from cooperation with Iran and Hezbollah in their increasingly sectarian war in Syria. This did not last long, as Hamas needed Iran’s support, alongside support from Qatar and Turkey. Nonetheless, Hamas has now congratulated the “brotherly Syrian people on their success in achieving their aspirations for freedom and justice.”

The fall of a brutal dictator like Assad is a historic event, first and foremost for the Syrian people. Their moment of triumph also confronts them with one of their greatest tests yet. Will a new Syria be a Sunni Islamist state? Will it be one state or remain fractured? And will a fractured Syria necessarily mean conflict and create no-governance zones, fertile ground for violent extremists, including the still active Islamic State (ISIS)? Syria’s neighbors and others are watching closely, with Israel already striking at chemical weapons stores that could fall into extremist hands, and the United States attacking ISIS positions. Others, too, would be ready to intervene as events unfold.

The Kremlin suffers a major setback

In September 2015, Russia launched its post-Soviet return to the Middle East by bombing rebels fighting the Assad regime—after giving the United States an hour’s notice about its military plans—thereby ensuring that the Syrian dictator remained in power. Russia subsequently expanded its military base in Tartus—its only warm water port—and acquired an air base in Hemeimeem, enabling it to project power and influence in the wider Middle East and beyond. Russia strengthened its relationship with Iran as they both propped up the Assad regime at the same time that Russia and Israel developed a coordination mechanism that enabled Israel to strike Hezbollah and Iranian targets. Russia’s Syrian foray played an important role in its return as a great power.

Bashar al-Assad’s fall is a major setback for Russia. With Moscow’s military resources overstretched in its war with Ukraine, it was unable to give Assad the support he needed as the rebels advanced. Vladimir Putin has granted the Assad family “humanitarian” asylum in Russia, and it is unclear what kind of relationship the Kremlin will be able to develop with the rebels whom Russian forces were previously fighting. If Russia were to lose its two Syrian bases, that would be a blow to its global presence; Moscow will do everything it can to keep these bases. Assad’s fall also raises questions about Russia’s reliability as an ally and partner.

Putin will no doubt seek to establish a relationship with the new rulers in Damascus. Until and unless he does, Russia’s role as a major Middle Eastern player is in question.

Assad's collapse highlights the role of Arab militaries

The spectacular collapse of the Assad regime has come at a breathtaking speed, only days after the rebels initiated their assault on government forces but more than a decade after many had anticipated its demise in the early days of the Arab uprisings that began in 2011. While Syria has its own unique features, the connectedness of its revolutionary change to trends in the rest of the Arab world is worth probing.

When the uprisings began in Syria over 13 years ago, they were empowered by the similar popular revolts that started in Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt. The outcomes in all these countries were as unpredictable as were the uprisings in Syria in the past 13 years—and will be in the coming period. In the time since the start of the Arab uprisings, a counter-revolution has taken hold in much of the Arab world, with autocratic regimes finding ways to fend off threats and entrench themselves further. Will the collapse of the Assad regime rekindle popular revolutionary spirit elsewhere?

One starting point is the role of the militaries in Arab revolts: In Tunisia, they pushed the president out; in Egypt, they did the same, but only in order to keep the military in control; in Libya, there was collapse under NATO airstrikes; in Syria, the military (with outside help) saved Assad. The most surprising part in Syria this time has been that the military seemed to abandon Assad, which apparently surprised him and his Iranian allies. As Arab rulers look for lessons, watch them show more love to their militaries.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Assad regime falls. What happens now?

Brookings experts weigh in

December 9, 2024