The July 2015 nuclear deal between Iran, the United States, and five other world powers triggered an intense debate in Washington and across the country. Nowhere was the contention surrounding Iran policy more impassioned or more urgent than in the U.S. Congress, whose mandate to review the agreement raised the stakes and greatly amplified the discussion.

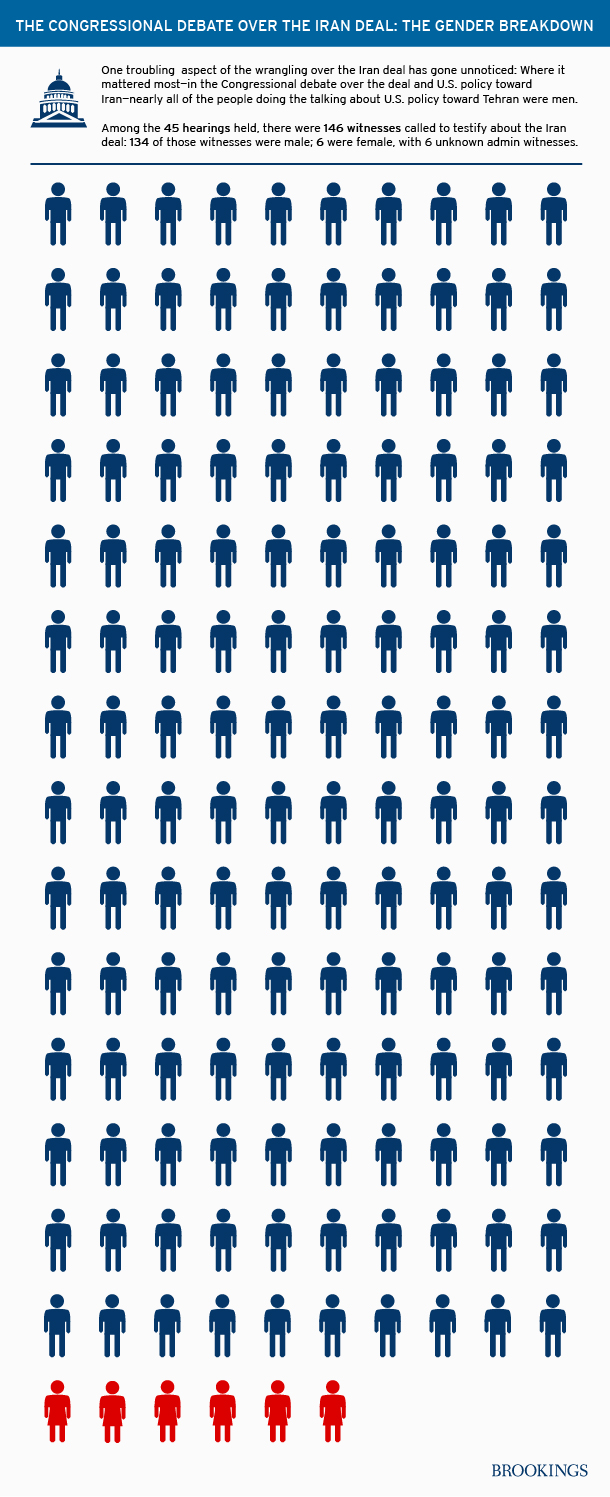

But one troubling aspect of the wrangling over the deal has gone unnoticed. Where it mattered most—in the Congressional debate over the deal and U.S. policy toward Iran—nearly all of the people doing the talking about U.S. policy toward Tehran were men. Women led the negotiations on the Iran deal; they covered every minute of the tortuous talks in the press; they debated the terms of the deal within academia and think tanks throughout the United States, Europe, and even Iran; they published thoughtful, informed analyses, both pro and con, that addressed everything from sanctions to proliferation risks to human rights to legislative procedure. Women played pivotal roles in shaping the legislative outcome to the deal. But when it came time to advise Congress on its fateful deliberations over Iran, women were almost entirely absent.

Truth in numbers

Congress took a powerful interest in Iran over the past year. By my count (compiled by reviewing the relevant congressional websites), House and Senate committees and subcommittees conducted at least 45 hearings that were primarily or solely focused on Iran between January 21, 2015 and January 20, 2016. And yet, at least 38 of those Congressional hearings featured panels comprised solely of men, and of the 140 named witnesses in these hearings, only six were women. (Note: there were also at least two closed Congressional hearings on Iran, featuring a total of six unnamed witnesses representing the Obama administration.)

Six women out of 140 witnesses: that’s about four percent women and 96 percent men. In other words, as Congress deliberated one of the most consequential foreign policy issues of the year, its members relied almost solely on male experts for advice and input.

If these were statistics from the Middle East, we’d be outraged, but probably not very surprised. After all, gender inequality remains one of the region’s defining challenges, enshrined in many countries’ laws through an array of restrictions on women’s legal status, limited access to education and employment, and inequitable family law. However, in the contemporary American foreign policy and academic communities, women are, well, essentially everywhere, as the Council on Foreign Relations’ Micah Zenko and Amelia Mae Wolf documented last year, even if senior ranks remain disproportionately male. And if you don’t know any women with expertise on Iran or the broader Middle East, then you simply haven’t been paying attention. In fact, the chief negotiators on the Iran deal for both the United States and the European Union were women, as are many other diplomats, analysts, journalists, academics, and activists who work on Iran.

So where were the women when it came time to debate the Iran deal on Capitol Hill? For full disclosure, I should acknowledge that I was one of the lucky six who testified last year. The other women who made the cut include Ambassador Wendy Sherman, then serving as the lead American negotiator on the nuclear deal and undersecretary of state for political affairs, as well as two academics and the spouse and mother of Iranian-Americans who were imprisoned by Tehran on trumped-up charges.

See a pattern?

Congressional hearings do not seek to provide the utmost expertise or a cross-section of opinion. These are inherently adversarial discussions, structured to clarify available policy alternatives by showcasing divergent witnesses, typically selected by partisan staffers to advance the most zealous arguments on behalf of their party’s position. As a result, Congressional testimony is overwhelmingly skewed toward strenuous partisans rather than a representative sampling of experts.

Moreover, underrepresentation of women is hardly a problem unique to Congress. My colleague Tamara Cofman Wittes has written a series of articles, along with George Washington University professor Marc Lynch, highlighting “dramatic disjuncture between presence and visibility” of women in public events hosted by Washington think tanks.

Ironically, the proportion of women who provided expert testimony on Iran policy this year was closer to the demographics of Iran’s own parliament.

Still, the gender imbalance in Hill testimonies on Iran—four percent female in 2015—is far more dramatic than that of the think tank community a year earlier, where representation of women ranged from 13 to 25 percent in Wittes and Lynch’s survey). And it is more severe than the disparity in the composition of Congress itself, where women comprise slightly less than 20 percent of the 535 members of Congress, with 20 female Senators and 84 representatives. Ironically, the proportion of women who provided expert testimony on Iran policy this year was closer to the demographics of Iran’s own parliament, where only nine of 290 current MPs are women, or three percent. I suspect that is a comparison that not many in Congress would welcome.

Wanted: same standards

I have to admit that it would be tempting to simply overlook the disparity. After all, there are even more stark disparities in my field with regard to race, ethnicity, and national origin. And as part of the Title IX generation, gender equity in education—and in professional settings—has always been a given.

In fact, I’m aware that my gender—along my national origin and other immutable factors—have probably provided a leg up at many points in my career. It certainly helped when I was doing doctoral research in Iran. As an American woman with no ancestral roots in the country, I was treated as a curiosity—a lark—in seeking interviews or data, and insulated from the worst kind of suspicion in a country where paranoia runs high.

So I’ve been a bit reluctant to launch a gender jihad, so to speak. But a process where women’s voices are almost entirely excluded, even if only inadvertently, seems inherently problematic. Few Americans would willingly embrace the overt discrimination against women that remains the norm in various corners of the Middle East. We scoff at the Saudi ban on women driving and find fault with mandatory veiling there and in Iran. We reject the strict segregation of the sexes that characterizes daily life in a handful of Islamic societies.

And yet in practice, the U.S. Congress also tacitly endorses the omission of women’s voices by by engaging in repeated exercises of expert consultation—45 hearings with 146 witnesses—that almost entirely consisted of men.

Widening the lens

Unfortunately, there are no easy solutions for rectifying the imbalance in women’s participation in Congressional deliberations, or more broadly in ensuring a truly representative balance in Washington discourse and decision-making. Quotas or mandates for female participation strike me, and many of my colleagues, as incredibly patronizing. Most of us don’t want to be in anyone’s “binders full of women,” to borrow a phrase from 2012 presidential candidate Mitt Romney. Our work is not gender specific, and we want to be judged just as our male colleagues are—on the value of our research and expertise. Unfortunately, however, that simply is not the case, at least as far as Congress is concerned.

Our work is not gender specific, and we want to be judged just as our male colleagues are—on the value of our research and expertise.

How can Congress do better in ensuring that women are included in the conversation? Wittes and Lynch’s articles highlighting the gender imbalance in thank tank events have provoked an important and sometimes uncomfortable discussion among and within research organizations that ought to be replicated on the Hill.

An important first step would entail gathering additional data to ascertain whether the issue of Iran is an anomaly, or whether there are broader patterns that can be discerned about women’s participation in the totality of Congressional testimonies. An infamous 2012 incident in which Democratic representatives walked out of a hearing on contraception and health insurance after the only female witness was disqualified suggests the absence of women consulted by Congress on Iran may not be unusual.

Either way, in the forthcoming year Congress can and must do better. As Iranian women organize in the face of steep obstacles to try to increase their representation in upcoming parliamentary elections, let’s ensure that no major national security issue—or for matter, no minor domestic policy issue—remains a boys’ club within the Congress, the branch of U.S. government that is supposed to represent all of the American people.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Talking about Tehran on Capitol Hill should not be a boys’ club

January 29, 2016