The death of George Floyd and other Black Americans and the uneven impact of COVID-19 have highlighted deep-rooted concerns about racial and urban inequality and segregation in America and the consequences of inequality for families living in persistent poverty.

Over the past several years, the research literature pointing to the relationship between racial segregation, enduring concentrated poverty, and long-term socioeconomic inequalities in the United States has been rapidly growing. Work by such scholars as Patrick Sharkey, Robert Sampson, and others, and novel experimental evidence produced by Raj Chetty has greatly increased our understanding of the detrimental – and multigenerational – consequences of being born and raised in an under-resourced neighborhood.

Long-Term Damage

Over the past forty years, the country has experienced sharp increases in urban poverty. The number of metropolitan neighborhoods in which 30 percent or more of residents live in poverty doubled between 1980 and 2010. Moreover, almost two-thirds of the high-poverty neighborhoods in 1980 were still very poor almost forty years later.

Being born and raised in grinding, persistent poverty damages children’s long-term outcomes. Moreover, when families live for long periods in such conditions it is not only deleterious to the family, but the impact on the family differs significantly by race. As Sharkey notes, Black Americans are far more likely than whites to be “stuck in place.” He found that two-thirds of Black Americans brought up in the poorest neighborhoods remain in the poorest quarter of neighborhoods after a generation; meanwhile only 40 percent of whites brought up in the poorest neighborhoods remain there. The long-term effects of being born and raised in a high-poverty neighborhood are thus far more persistent and damaging for Blacks than for whites.

The proportion of Blacks encountering that pattern is also greater than for other groups. Today, one in four Black Americans are stuck in high-poverty neighborhoods, compared with one in six Hispanics and just one in thirteen white Americans, according to a report by Paul A. Jargowsky for the New Century Foundation. Adding to the generational barriers facing young Black Americans, a 2018 study by Chetty finds that, after controlling for parental income, Black boys have lower incomes in adulthood than white boys in 99 percent of census tracts.

Example: Washington, D.C. and COVID-19

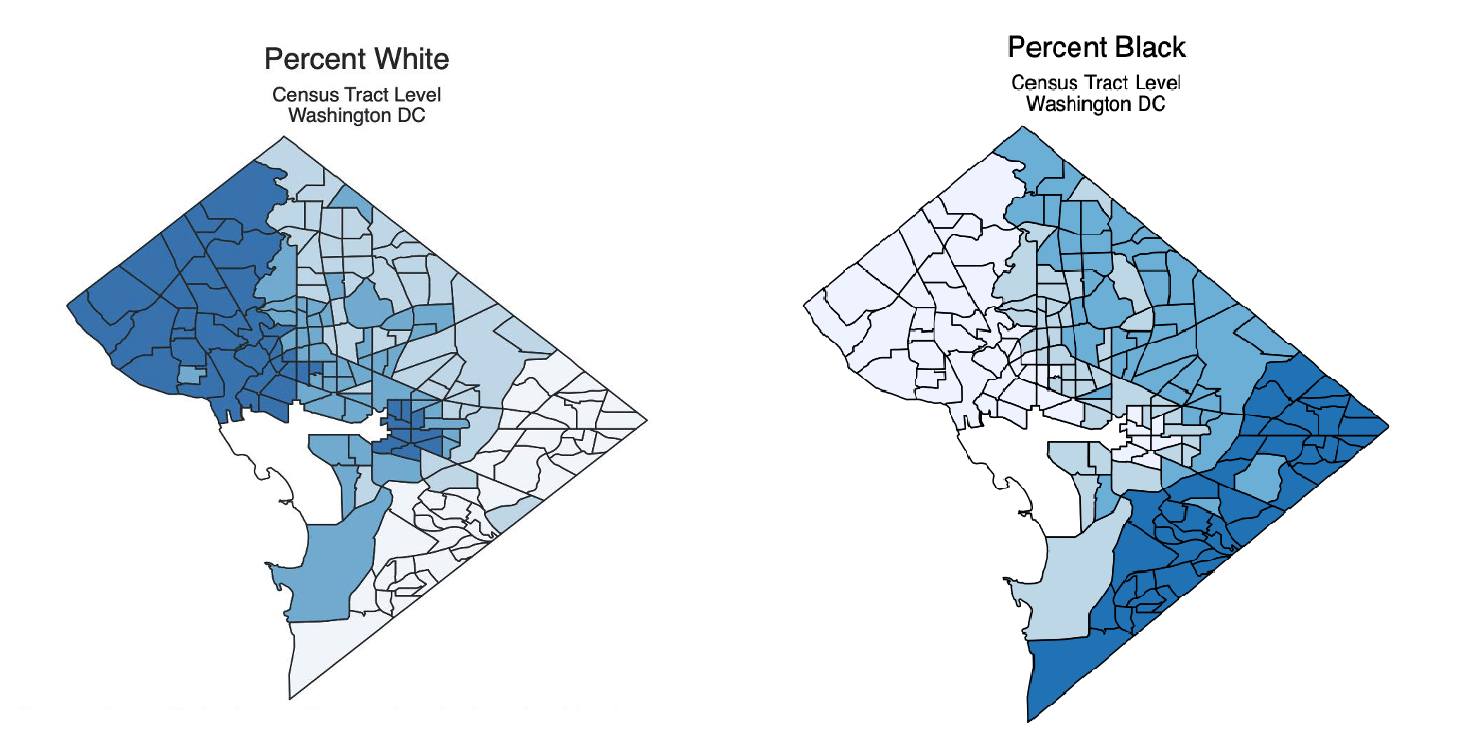

Washington, D.C. is a case study of how race and poverty closely overlap and how damaging racial segregation and poverty persists even in the nation’s capital. In a previous blog, we showed how the District of Columbia remained mostly segregated along east-west lines between 1990 and 2010. Moreover this “two cities” segregation was reflected in significant inequalities in urban poverty: some 94 percent of D.C. neighborhoods with a majority white population had less than 10 percent of their families living below the poverty line, while that was true of just 22 percent of majority Black neighborhoods.

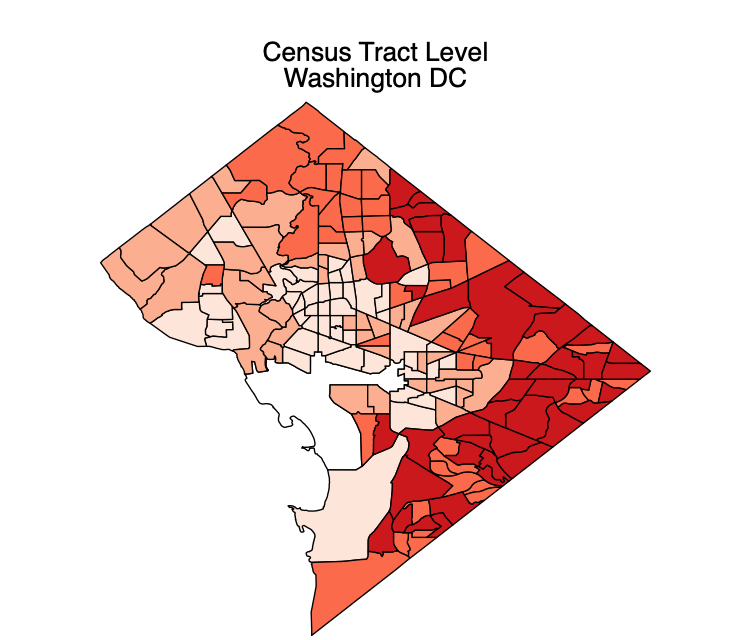

This segregation in D.C. and other cities is linked not only to economic outcomes. It also shows up in susceptibility to many illnesses, such as COVID-19. The COVID-19 vulnerability index, released by the nonprofit Social Progress Imperative, harmonized a broad range of datasets to create a Census-tract-level, weighted-index of vulnerability of contracting COVID. The index is built out of sixteen indicators that map onto the following three themes: population demographics, underlying population health issues, and health infrastructure[1].

Mapping the vulnerability index to D.C. underscores the east-west divide (Figure 2) and closely mirrors the sharp racial Black-white split in the city (Figure 1). The mapped vulnerability index indicates that Black Americans are at greater risk of infection, underscoring the pernicious effects of urban segregation and poverty. This is particularly worrying, given the rapid spread of the virus across the nation’s capital. Moreover, Black Americans are also more likely to face severe housing cost burdens and housing insecurity related to COVID-19.

Figure 1. White-Black racial divisions in Washington, D.C.

Figure 2. COVID-19 vulnerability index in Washington, DC

Taking Steps to Reduce Persistent Neighborhood Poverty

In addition to addressing structural racism and segregation in America, there needs to be a two-pronged strategy to tackle the problem of people stuck in persistently poor neighborhoods.

Strengthening communities. The first prong is to take steps to address the factors that make it likely that poverty and segregation will persist in neighborhoods by strengthening the economic and social fabric of the community. This means community-led strategies to spur economic improvement. Crucial for that objective are such actions as improving public schools and transportation, reducing crime, providing better health care, increasing access to healthy food options, and encouraging local entrepreneurship.

To be sure, that strategy poses a dilemma. Making a neighborhood more attractive as a place to live, work, and do business will lead to the benefits of more diversity and opportunity; but it also could lead to higher housing costs and the potential displacement of some existing lower-income residents. That pattern – a feature of “gentrification” – is seen in many Washington, D.C. neighborhoods as well as many other U.S. cities. Thus, tackling the roots of persistent poverty must be combined with actions to help make sure existing residents and local business owners can remain and share in an improving neighborhood. This requires government actions such as rental assistance for families, inclusionary zoning, and encouragements for developers to construct affordable multi-family housing. In addition, local governments need to promote employment training, apprenticeship programs, incentives for local hiring, and other steps to make it more likely that long-time residents can acquire new jobs in an improving community. And governments need to help build a foundation of homeowners among modest-income renters, such as through versions of Washington D.C.’s Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) program. This program enables groups renters to purchase their building as a co-op, but it prevents the new owners from selling their shares at market rates, thereby helping to retain a continued supply of affordable units for purchase.

Moving out. While strengthening the assets and opportunities within a persistently poor neighborhood is the preferred approach, in some neighborhoods that is extremely difficult. Thus a second important prong is to also to make it easier for families to move to areas with more resources and employment opportunities. In a 2015 study, Chetty examined a dataset of over five million families who moved across counties in the United States. He found that every additional year of childhood spent in a better environment significantly improves a child’s long-term outcomes. Strikingly, the study found that at least 50 percent of the variation in intergenerational economic mobility across the nation can be linked to the causal effects of neighborhood exposure during childhood. (Intergenerational mobility is a measure of the change in economic circumstances from one generation to the next.)

For some time, the research community was uncertain about the impact on earnings and educational success from encouraging families to move to better neighborhoods. To explore this, Chetty examined the Moving to Opportunity (MTO) program – a 1990s social experiment that examined the consequences of enabling low-income families with children in high-poverty neighborhoods to move to other communities. Chetty found that the positive effects on low-income households are strongest for pre-adolescent children, especially younger children (i.e. the group most harmed by living in persistent poverty). Moreover, the most noticeable impacts show up when these children reach college and working age, including increased college attendance and earnings, and reduced rates of single-parenthood.

Chetty concluded that policy should make it easier for low-income families to move from persistently poor neighborhoods to areas of greater opportunity through such policies as expanding housing vouchers and other rental assistance programs. To expand the supply of reasonably affordable housing available to such families in other neighborhoods, rental assistance needs to be combined with steps to increase the supply of affordable housing in more upscale communities through inclusionary zoning and other land-use reforms. And to make affordable housing more available to lower-income families moving to neighborhoods with more resources, this is the time to strengthen fair housing requirements. It is not the time to undermine them, as the Trump administration sought to do with its July 2020 rule change, which gives communities greater latitude to weaken the requirements.

An emphasis on access to opportunities. In parallel with these two approaches is the need to increase access to opportunities by better integrating cities. Promoting regional initiatives aimed at increasing the connectivity and mobility of urban residents, and connecting communities to regional assets and opportunities, making it easier for people in different communities to interact. This typically requires the expansion of an affordable transportation infrastructure. It also means attention to the heavy burden that urban sprawl and traffic congestion imposes on the poor, by encouraging greater urban density and building affordable housing closer to the city centers – creating greater proximity to jobs and services.

Mounting research underscores the damaging long-term effects for families of living in a segregated, under-resourced neighborhood. The research also indicates the benefits of enabling such families to move to areas of greater opportunity, especially for younger children; it also shows the importance of increasing diversity and resources within persistently poor communities. Growing evidence points to a series of public policy tools which can help obtain these results. What is needed now is a much greater determination to use them.

The authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. They are currently not an officer, director, or board member of any organization with an interest in this article. The views presented here are those of the authors and do not represent the views of The World Bank or The Members of the Executive Board of Directors.

Shapefiles and geographic boundaries for graphs obtained from: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry/ Geospatial Research, Analysis, and Services Program.

[1] The full set of factors that were included in the analysis are included here: http://us-covid19-risk.socialprogress.org/

Commentary

Tackling the legacy of persistent urban inequality and concentrated poverty

November 16, 2020