Rising housing costs have become an increasingly salient political issue for state-level elected officials across the United States. Local governments have traditionally exerted the most direct control over land use and housing production, yet political and fiscal incentives align to pressure local officials into restricting new development, especially of moderately priced homes. However, state governments are increasingly feeling the pinch of poorly functioning housing markets in several ways. Inadequate supply, especially in near job centers and transportation infrastructure, makes it harder for companies to recruit and retain workers. Most new housing is developed on the urban fringe in car-dependent locations, leading to higher traffic volumes and more greenhouse gas emissions. Exclusionary zoning by affluent, high-opportunity communities restricts economic mobility and exacerbates racial and economic segregation. In short, the economic, social, and environmental costs of poorly functioning housing markets spill over beyond local boundaries to affect entire regions and states. State-level action has the potential to improve these outcomes.

In a new study, I examine what state governments can—and should—do to encourage healthy housing markets. I identify four broad goals to guide statewide housing policies, discussed in more detail below. To illustrate the range of existing state policy approaches, I examine the types of policies uses by five contrasting states: California, Massachusetts, Oregon, Utah, and Virginia. To achieve any particular goal, states can use a variety of different policy tools, giving them flexibility to design an approach that fits their economic needs, institutional capacity, and political circumstances.

Goal #1: Analyze state housing market conditions to design appropriate policies

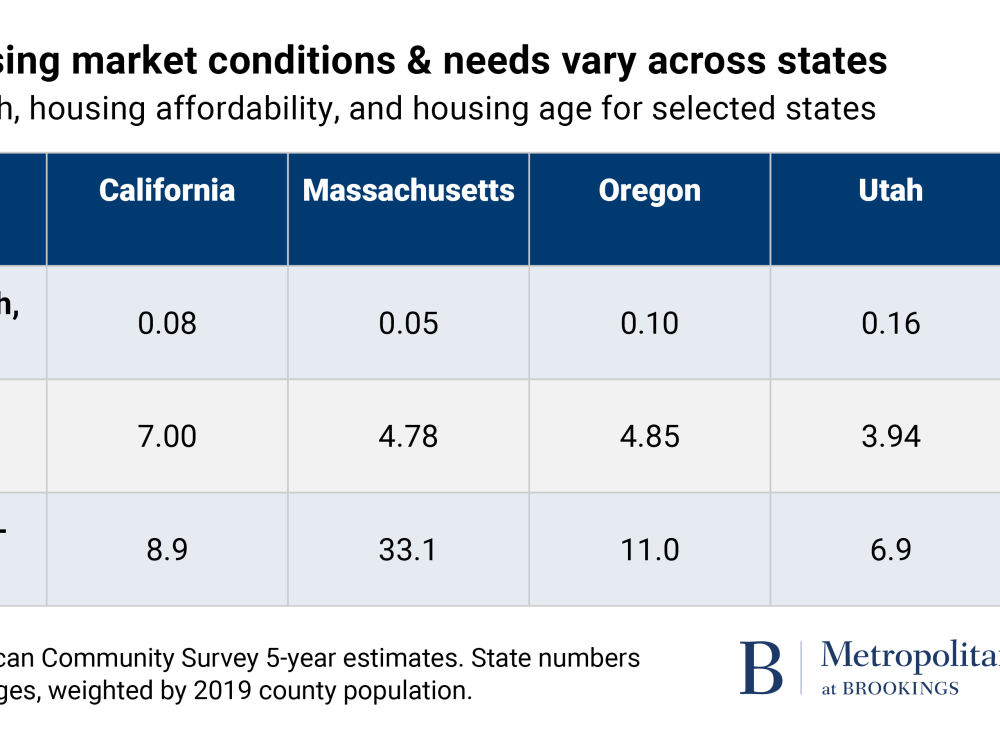

Before adopting or amending housing policies, state leaders should use data to identify key needs and challenges, and design their interventions accordingly. Comparing a handful of simple metrics across the five sampled states illustrates how differences in underlying market conditions can inform policy choices (Figure 1).

Population growth is a primary driver of housing demand: Fast-growing places need to build more housing to accommodate more people. Utah counties experienced by far the highest average population growth (0.16) between 2009 and 2019, three times as high as Massachusetts counties. This implies that the typical Utah locality will need to expand housing supply more than localities in other states, particularly slow-growth states like Massachusetts.

A helpful affordability metric is the ratio of median home values to median household incomes. Value-to-income ratios between 3 and 4 are considered healthy, because they imply that the typical household could buy a home while spending about one-third of their monthly income on housing. Of the studied states, only Utah and Virginia fall in that range. California has (unsurprisingly) the most expensive housing, with median home value-to-income ratios around 7.00—well above any threshold for “affordable.”

The final metric, the share of housing built before 1940, is a proxy for housing quality. Older homes typically have higher maintenance needs, including lower energy efficiency. Massachusetts stands out for having a very large share of older housing.

Although specific policy priorities and strategies will vary across states, based on underlying housing market conditions, most states could benefit from policies to address the next three goals:

- Encourage housing production in places with strong demand

- Provide financial support to low-income households,

- Reduce climate risks

Goal #2: Encourage housing production in places with strong demand

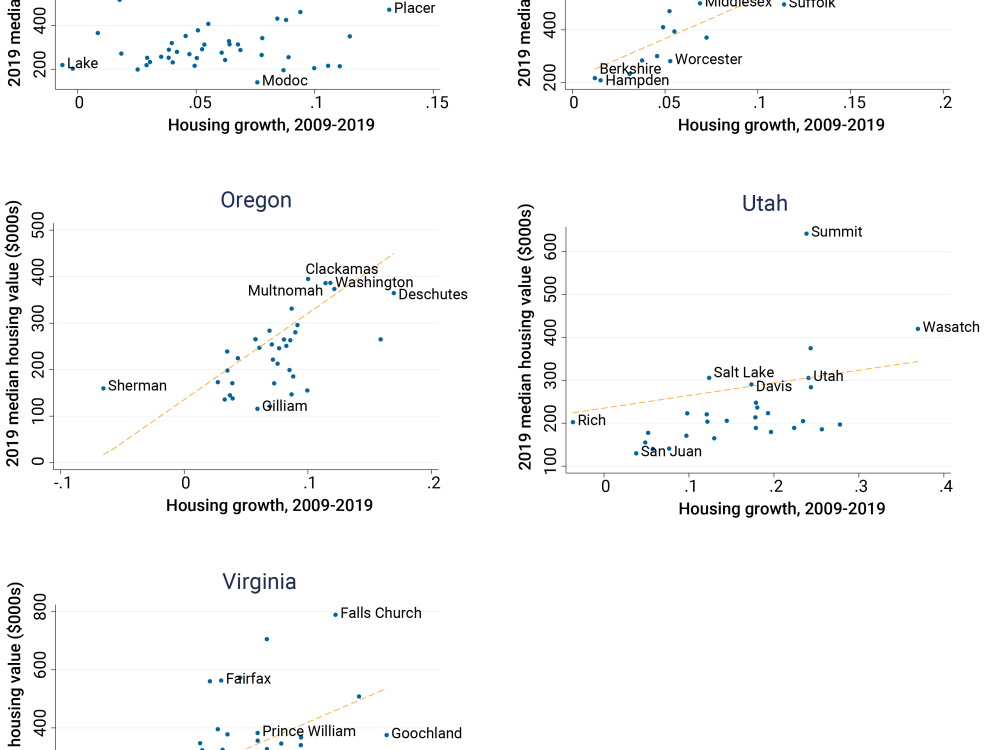

Current debates over how statewide zoning reform start with the assumption that local governments are overly restrictive of housing, needing more state oversight. This raises the question: Are strict zoning and limited housing production prevalent across all (or most) localities within states? One simple diagnostic is to look at the relationship between housing growth and prices or rents: In well-functioning housing markets, places with strong demand will add more housing, while places with weak demand build very little.

Graphing county-level housing values and changes in the number of homes for our sample states shows the expected positive relationship in four states (Figure 2). In Massachusetts, Oregon, Utah, and Virginia, counties that had higher population growth from 2009 to 2019 had higher housing values in 2019. (Counties offer a consistent unit of analysis across states, although cities and towns also play important roles in land use regulation.) California is the one exception: The more rapidly growing counties are among the least expensive. This corresponds with prior research that affluent counties have the most restrictive regulations and generally oppose new development.

States have at least four different strategies to incentivize local governments to allow more development in places with strong demand. These can be designed either to apply to all localities within a state or targeted towards specific places where supply lags demand. Broadly defined, these strategies include:

- Financial carrots and/or sticks tied to quantitative housing production targets

- Oversight of local land use planning

- Create a “builders remedy” that allows developers to override local zoning under certain conditions (for instance, to construct below-market-rate housing),

- State pre-emption of specific zoning rules

Over the past few years, several states have focused on preemption of narrowly defined rules, especially zoning bans on accessory dwelling units (ADUs) and duplexes. However, the most effective policies will target improved housing outcomes, such as increased production or affordability. Land use regulations are complex and multi-layered, making it easy for localities that don’t want to produce housing to appear compliant on paper while actually not building anything. For example, a city’s zoning might technically allow duplexes, while large setback requirements or low floor-to-area ratios make them financially infeasible or impractical.

Goal #3: Provide financial support to low-income households

Even in well-functioning housing markets with abundant housing, the poorest 20% of households in all parts of the U.S. cannot afford even modest market-rate housing without subsidies. This is primarily a reflection of very low wages, and so can be most directly addressed by giving poor households direct financial assistance. Because federal housing subsidies are not an entitlement, only one in four poor renters receive any federal rental subsidy. States have a number of different ways they can support low-income households including:

- Household-based rental assistance, such as vouchers and homelessness prevention services

- Supply-side rental assistance, including the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program

- Subsidies to help low-income homeowners with maintenance and utility costs,

- Down-paymentassistance for first-time homeowners

Goal #4: Reduce climate risks

Land use regulation and building codes are part of the toolkit available to state governments to reduce the risk and harm of climate change. Ideally, state environmental protection laws should discourage development in risky and/or sensitive locations (e.g. flood- and fire-prone areas) and encourage climate-friendly homes (energy efficient materials, structures, and locations), while not unduly restricting overall housing stock relative to population and job growth. In practice, states often struggle to balance these goals. The clearest example is California’s landmark environmental protection law, CEQA. Adopted in the 1970s with the intent to limit environmentally damaging development, in recent years CEQA has been weaponized by NIMBY homeowners to block projects with broad public benefits, including climate-friendly projects like bike lanes.

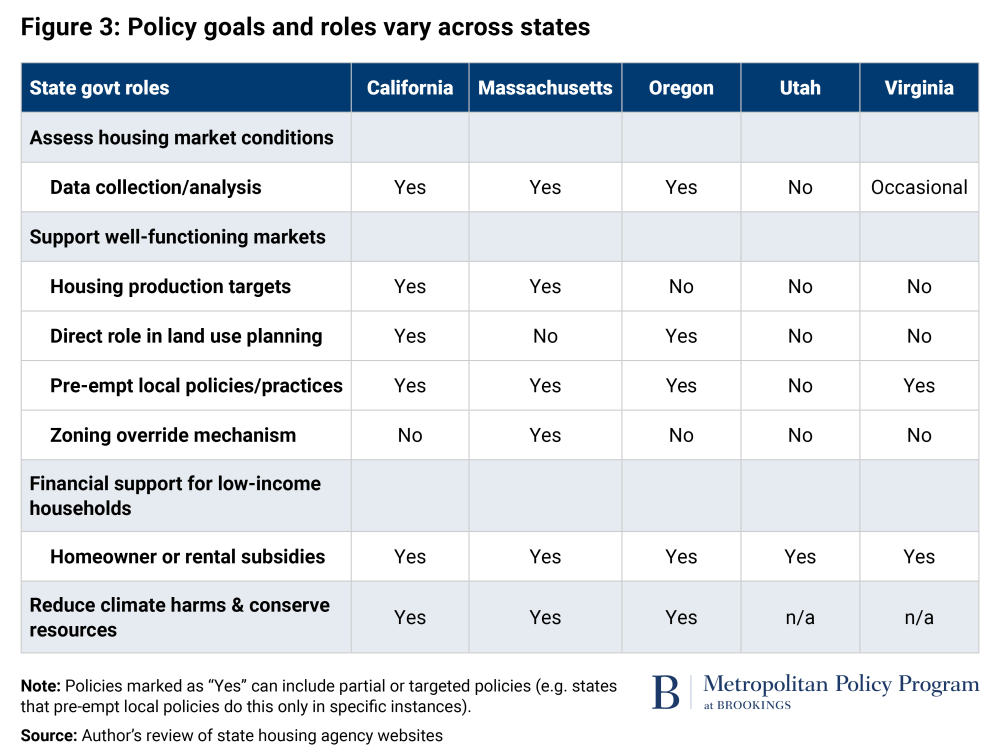

Current state housing policies start from widely varying baselines

Housing policies in the five studied states vary along several important dimensions. They represent different points along the intensity and complexity of current policies, from highly complex (California) to lightest touch (Utah and Virginia). The states’ legal and institutional structures—the framework within which localities operate—also vary widely. California sets housing production targets for metro areas and localities—although these targets have not been effectively enforced. California and Oregon have explicit statewide mandates to monitor land use planning and/or housing production. Massachusetts has a statewide “fair share” rule focused on low-income housing, which allows developers to override local zoning under certain conditions. All five states offer some types of housing subsidies, but differ in the target populations and activities. Figure 3 summarizes high-level differences in how each state addresses the four policy goals; specific policies and institutional structures are discussed in more detail in the longer report.

Getting policy just right requires good data, careful planning, and a willingness to experiment

Because states currently start from such different baselines—both in market conditions and institutional capacity—there is not one consistent set of recommendations that will work for all states. California would benefit from simplifying and streamlining its many complex programs and regulations. Virginia and Utah will need to start slowly, assessing current needs and building up staff capacity. With that caveat, three general rules of good policy can benefit all states.

- Do your homework. Thoughtful data analysis is the foundation of solid policy.

- Experiment, evaluate, and tweak. It’s hard to get policy “just right” on the first try, especially in such a complex and fast-changing market. Implementing pilot programs that can be evaluated and tweaked before rolling out at scale can help deliver better long-term results.

- Keep things simple. Complex policies and regulations require more staff time and resources to administer and oversee and impose higher administrative burdens on grant recipients to comply.

- Think hard about unintended consequences. Policies can have ripple effects that undermine their primary goals—and it’s very difficult to reform or repeal harmful policies (like California’s CEQA and Prop 13) once they become deeply entrenched.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).