Editor’s Note: This blog post is in response to the newest Brookings Essay, “The Bad News About the News,” by former Washington Post Editor Robert G. Kaiser.

Robert Kaiser’s essay admirably surveys the problems facing journalism. I want to add a few thoughts about where the replacement for lost ad revenues may come from—and about some potentially troubling implications, including for Kaiser’s great paper, The Washington Post.

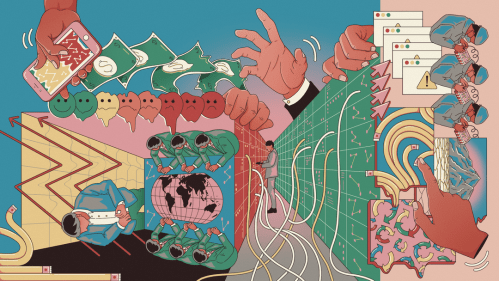

Over the past 50 or more years, we journalists have had the luxury of thinking of journalism as our product, and of readers as our customers. It was a great ethic to maintain, but from an economic point of view it was never right. In the newspaper business, our real customers were our advertisers, who paid the bills; our product was our readers, whose eyeballs we sold to advertisers; our journalism was our marketing hook, luring readers. Now that our marketing hook can no longer deliver our product competitively to our customers, our customers—advertisers—are going away.

The question now is: who is our next customer, if in fact we have one? I suspect part of the answer will be: corporations, investors, and other business interests that can harness journalistic methods and talent to promote their interests and brands.

One example, emerging rapidly, is so-called “native content” (aka “sponsored content” or “branded content”), which Wikipedia nicely defines as “a form of online advertising that matches the form and function of the platform on which it appears”: in other words, paid-for content that mimics the surrounding journalism but is produced for and placed by advertisers seeking to burnish a brand or disseminate a message. This stuff is often written by accomplished journalists to high professional standards, so it’s readable and interesting, sometimes better than the “official” goods. Don’t snicker, purists! In a provocative post recently (“Brace for the Corporate Journalism Wave”), Monday Note’s Frederic Filloux puts traditional journalists on notice that native content will eat their lunch. It will be free; it has a business model; readers will like it; and it will enjoy preferred access to the corporate insiders who are, after all, paying for it.

Or what if, instead of just buying ads that look like content, a corporate chieftain buys a whole newspaper? Every morning I thank Jeff Bezos, the founder and CEO of Amazon.com, for rescuing the Post, a national treasure, but I doubt he did it only for his health. If a giant company is engaged in cutthroat competition with other giant companies, and if it has all kinds of vital interests before the government, the country’s second most powerful newspaper might be a handy thing to have. I have no reason to think Bezos would slant the Post’s coverage of, say, electronic retailing or antitrust regulation, but how can the public be sure? And bundling Post content with Amazon’s dominant Kindle platform would give the Post a leg up: good for the Post, but potentially not good for other outlets that lack comparable access.

This new age is already here. I hear stories from friends in PR about ostensibly independent bloggers who, under the pressure of time, reword corporate press releases and post them online as news, or even ask PR people to write news items for them. I don’t know that the cultural wall between traditional journalism and corporate PR will come down completely, but I do know that “down” is the direction it’s going.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Sponsored Journalism May Transform Journalists into Commodities

October 17, 2014