When I think back to my days in elementary school, I still remember reading “How to Eat Fried Worms” in second grade, dissecting a cow’s eye in third grade, and mastering long division in fifth. These lessons do not just make elementary school interesting (OK, I never found long division interesting), they set my classmates and me up for success. Because of these early lessons, we were better able to tackle more sophisticated novels, understand the functioning of other organs, and grasp higher-level mathematics.

Although most educators understand the value of layering and building on core competencies, for some reason these same principles seem overlooked in how we train our future cadre of school teachers. Elementary teachers need a foundation of core knowledge they can draw upon to teach their students. Unfortunately, though, teacher prep programs do little to ensure aspiring elementary teachers learn the core content they need to thrive in their careers.

In our new report, A fair chance: Simple steps to strengthen and diversify the teacher workforce, my co-author, Kate Walsh, and I examine course requirements in more than 800 undergraduate teacher prep programs and 250 graduate programs. We found only a handful of training programs either required that elementary teacher candidates take courses in core topics like elementary math, world literature, U.S. history, or biology, or test candidates early enough to guide them toward the coursework they need.

Misaligned course requirements

Elementary teachers, no matter where they work, can expect to teach English language arts, math, science, and social studies. Within each subject is a set of topics (e.g., within social studies is U.S. history, world history, geography) that reflect content on licensing tests, as well as what experts, research, and state standards say elementary teachers need to know. Yet, these expectations are not explicitly required of most college students who prepare to be an elementary teacher.

Of course, most teacher preparation programs do require general education courses that touch on most or all of these subjects. Commonly, though, teacher candidates are given great leeway in deciding what courses to take to develop these competencies. This means that an aspiring teacher could take Chemistry 101 (helpful if she hasn’t taken a chemistry class since freshman year of high school), or she could take Chemistry and Art Restoration (interesting, but likely not important for teaching elementary grades). Even more, teacher prep programs rarely test incoming candidates to see whether they already know basic chemistry.

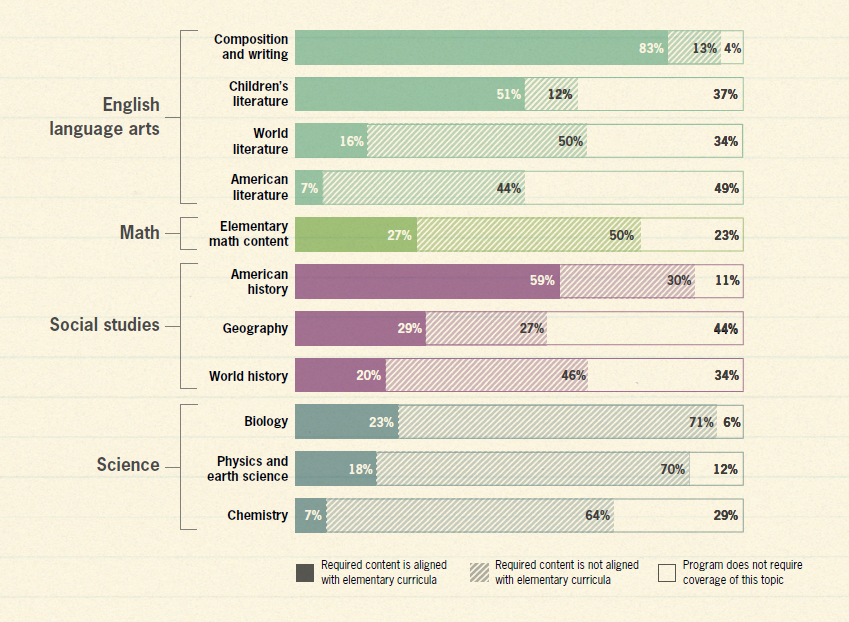

As the figure below shows, this flexible approach means that many candidates can flourish in their teacher training program only to flounder on the licensing test or on the job due to the gaps in their foundational knowledge. For example, we find only 7 percent of undergraduate training programs either check that candidates know chemistry or require a chemistry course aligned with what elementary teachers need to know. As shown in Figure 1, these data look nearly as grim in many other topics. Only a quarter of programs require adequate elementary math coursework, while nearly as many programs do not require any elementary math content coursework at all. Though more than half of programs require an aligned American history course, only one in five require an aligned world history course.

Figure 1. 817 undergraduate programs’ approach to elementary content knowledge

Implications for those who reach the classroom—and those who are blocked from it

This misalignment has costly consequences—the most obvious is seen in licensing test passage rates. Most states require aspiring teachers to pass one or more tests on topics such as basic skills, content, and pedagogy to become licensed to teach.[1] Only five states exempt some teachers from content tests (e.g., in Hawaii a test is one of five options for how to demonstrate content knowledge). Generally, candidates are allowed to retake all or portions of the test multiple times, although ETS (a major test vendor) finds that few candidates take a test more than twice.

This is where the costs of misalignment come in. On the most commonly required elementary content licensing test, more than half of test takers fail the first time they take it. After allowing for multiple attempts (retakes that cost both time and money to the candidate), one in four people still fail.

There are also costs on the demographics of the teacher workforce, since candidates of color are hit hardest. Only 57 percent of Hispanic test takers and 38 percent of black test takers pass, even allowing for retakes. This means that school districts, cognizant of the substantial research showing the importance of students of color having teachers of color, are missing out on more than 8,000 aspiring teachers of color each year who want to teach, and who enter teacher prep programs, but do not pass the licensing exam and so cannot earn a standard teaching license.

“Candidates of color are hit hardest. Only 57 percent of Hispanic test takers and 38 percent of black test takers pass.”

Finally, there are costs to the abilities of even those teachers who clear all of the hurdles. Many teachers who successfully pass their state’s licensing exams (which vary in rigor) and are hired as elementary teachers still report not feeling confident in their knowledge of the content they are expected to teach. Based on the Report of the 2012 National Survey of Science and Mathematics Education, only 54 percent of elementary teachers feel well prepared to teach geometry, 47 percent to teach social studies, and 39 percent to teach science.

Simple tweaks could help

Unfortunately, the data needed to examine the relationship between teacher prep programs’ course requirements and their passing rates on licensing tests are simply not available. Few states report either first-time or final passing rates publicly, and no one reports it on the program level (an important caveat, given that graduate programs devote less attention to content than do undergraduate programs). And the pass rates reported to the U.S. Department of Education as part of Title II reporting requirements are simply inaccurate. Many institutions’ pass rates are listed as 100 percent because the reported data only reflect pass rates for program completers and many programs require passing the test as a condition of program completion.

The result of these missing data is that we cannot definitively know whether requiring more aligned coursework would help candidates do better on licensing tests—or teach this content more competently once in the classroom. Regardless, we think it’s a safe bet and an easy fix for teacher training programs.

We also believe that diagnosing content needs for all aspiring candidates early in college and requiring relevant content coursework could boost passing rates for candidates of color. National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) data consistently show that 12th grade students of color leave high school with large gaps in core content knowledge—but students who took a rigorous course of study in high school tend to perform significantly better on NAEP exams. To us, this is suggestive evidence that requiring a stronger series of coursework later in college may be a viable way to boost candidates’ preparation for licensing exams.

Stronger content knowledge may not eradicate gaps in passing rates, but making these feasible changes in aspiring teachers’ preparation would be a big step in the right direction.

Footnote

- There are currently 22 content licensing tests on the market, offered by ETS and Pearson. State testing requirements vary in rigor, and some states some require candidates to separately pass each subject, while others combine multiple subjects together, allowing a candidate’s strength in one area to mask a weakness in another. For this study, ETS provided data for the “Praxis Elementary Education: Multiple Subjects” test based on a 3-year period. This test is required in 18 states and is optional in five more.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).