This piece is adapted with expansion from the author’s introduction to “The Sadat Lectures: Words and Images on Peace, 1997-2008” (Washington, DC: U.S. Institute of Peace Press, 2010).

To understand the international reactions to 9/11 and the Afghan war, it’s enlightening to consider the reaction and the rapid evolution of positions of one of the greatest statesmen of the 20th century, former President of South Africa Nelson Mandela. His shifting positions over a short period of time speak volumes about America’s squandering of the global goodwill that came our way in the immediate aftermath of the horror.

To understand the international reactions to 9/11 and the Afghan war, it’s enlightening to consider the reaction and the rapid evolution of positions of one of the greatest statesmen of the 20th century, former President of South Africa Nelson Mandela. His shifting positions over a short period of time speak volumes about America’s squandering of the global goodwill that came our way in the immediate aftermath of the horror.

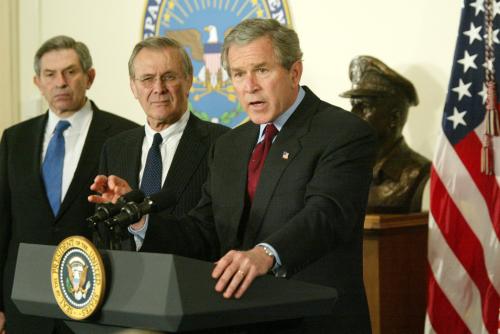

A critic of the West and of American foreign policy, Mandela — who had left office two years prior — was an unlikely supporter of President George W. Bush, visiting him at the White House just days after the Afghan war commenced. Speaking after his meeting with Bush at our Sadat Lecture for Peace at the University of Maryland, Mandela reflected on the widespread international sympathy and support the United States had received immediately after 9/11, even from usually antagonistic states like Iran. Mandela described his position this way:

“We have had occasion to express ourselves publicly in support of the current military actions by the United States and Britain in pursuit of those they identified as the perpetrators of the acts of terror. We accept that the United States and Britain are bent on bringing to book the identified terrorists and that the unfortunate civilian casualties that arise are coincidental. We accept that they will and are taking all precautions possible within a war situation to minimize civilian casualties and suffering.”

Back in South Africa two weeks later, facing criticism for siding with American action in Afghanistan, Mandela continued to defend the United States: “I support the strikes against Afghanistan as far as it is intended to flush out Osama bin Laden. I have no sympathy with terrorists who kill 5,000 innocent civilians. I cannot tolerate that.” Within two weeks, however, his support for the Afghanistan war was giving way to concern about the scope of the war and rising civilian casualties: “I never supported the bombing of the whole of Afghanistan and the killing of innocent children, elderly people, women and the disabled. I confined myself to bin Laden and his organization.”

Mandela’s position continued to evolve in a manner that reflected not only his own thinking but changing international attitudes. In January 2002, as the American discourse became more strident after early successes in Afghanistan and talk increased about possible military action in Iraq, Mandela had second thoughts even about his early support for the Afghan war:

“Our view may have been one-sided and overstated… such unreserved support for the war in Afghanistan gives the impression that we are insensitive to and uncaring about the suffering inflicted upon the Afghan people and country… Labeling of Osama bin Laden as the terrorist responsible for those acts before he has been tried and convicted… could also be seen as undermining some of the basic tenets of the rule of law.”

But like many around the world, Mandela’s biggest criticism of American policy was aimed at its perceived unilateralism as Washington geared up for the Iraq War. In September 2002, Mandela stated “We are really appalled by any country, whether it be a superpower or a small country, that goes outside the United Nations and attacks independent countries.” By January 2003, Mandela was increasingly frustrated by the American march toward the Iraq War, describing the U.S. stand on Iraq as “arrogant” and Bush as “a president who can’t think properly and wants to plunge the world into holocaust.”

Certainly, by the time the United States commenced the Iraq War, Mandela wasn’t the only one who had doubts about America’s goals. A 2002 Pew Research Center poll showed falling U.S. favorability ratings since 2000 across most countries studied. And concerns about possible war with Iraq were already obvious, as the poll found huge majorities in France, Germany, and Russia opposed the use of military force to topple the Iraqi regime. In contrast to the broad coalition of nations it had assembled for the Afghan campaign, Washington failed to get backing for the Iraq War not only at the United Nations Security Council but also from key European allies like Paris and Berlin.

If the U.S. had hoped that the Afghan campaign and the “war on terror” could win over people in Muslim-majority countries, the evidence shows it badly failed. Lacking what Robert Wright termed “cognitive empathy” toward people in target countries, the campaign was bound to fail in achieving its intended results. In polling I conducted in six Arab countries starting in early 2003 — just before the start of the Iraq War — and ending a decade later, most Arabs consistently ranked the U.S. second only to Israel as the biggest threat they faced (and sometimes first); most attributed American policy in the region to a drive to control oil, help Israel, and weaken the Muslim world; and those who believed that the U.S. was seeking to achieve democracy, spread human rights, or even bring stability to the region were comparatively few (see chapter 7 of my book “The World Through Arab Eyes”). The “war on terror” itself was increasingly seen as a war on Muslims, and most of those who had any positive thoughts about al-Qaida at all tended to have those thoughts principally because they thought al-Qaida was standing up to the United States.

Back to Nelson Mandela. The regret he came to have even about his early support for what he assumed would be a limited and measured military campaign in Afghanistan raises a central question: Was the war path doomed from the outset? Sure, a more measured response to the attack on American soil was theoretically possible, with a much earlier ending and fewer casualties. But given the agendas driving the Bush administration’s response, the worldview of the influential neoconservative camp, the way the “war on terror” was defined, and the early permissiveness of the American public in rallying behind the flag — one wonders if the campaign was doomed as soon as it started, and whether Congresswoman Barbara Lee, the lone opponent of the war in Congress, saw what no other member could in a moment of great grief, fear, and anger. Even a seemingly war-weary president, Barack Obama, found himself vastly expanding the scope of the war on terror, despite finding and killing bin Laden a decade ago.

It could have theoretically all ended much earlier, with the rapid fall of the Taliban regime, just a few short weeks after the fighting commenced. But as I noted in my 2002 book, “The Stakes: America in the Middle East”:

“The shift in America’s mood in the months after that horrific day in September was breathtaking in its scope and unprecedented in its speed. From the strongest sense of vulnerability in recent history to the most strident self-confidence in memory after the seemingly easy success in toppling the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, the journey took but a few months. At some level, this rapid journey was healing to a nation whose confidence had been painfully shaken. At another level, it was troubling. Certainly, America has experienced many radical swings in its foreign policy in the past. But from the isolationism that followed World War I, carried out to a disastrous extreme as witnessed in Pearl Harbor, to the ensuing interventionism that ended with quagmire in Vietnam — the swings were almost generational. Rarely have such extreme shifts in mood been more rapid than in the autumn of 2001 — and perhaps rarely as consequential.”

That stunning swing in the public mood gave birth to a troubling stridency, further enabling a policy that went beyond the Afghan quagmire, leading us to the “shock and awe” in Baghdad and a torturous occupation of Iraq with even more destructive consequences. Those who voted to authorize the Afghanistan and Iraq wars could later tell themselves that what we ultimately got was not what they had voted to authorize, or that all could have turned out differently had we done this or that. Maybe or maybe not. But at this post-war moment, when the devastation should be clear, we must honestly consider whether things could have turned out much differently, given what we knew about those making the decisions and about our flawed politics. And we must draw careful lessons before an unforeseen crisis tempts us into another violent path.

Commentary

September 11 and America’s response through the eyes of Nelson Mandela

September 9, 2021