Amid funding and programmatic uncertainty, many communities are testing new plans, exploring new financing tools, and even rethinking how they govern and operate their water infrastructure. Aging distribution pipes, overwhelmed sewers, and other vulnerable systems not only pose environmental and public health risks, but also strain state and local budgets, as well as those of the public utilities that own and operate this infrastructure.

Now, “regionalization”—collaborations or partnerships among geographically proximate local water systems—is gaining renewed momentum nationally as a potential solution. But the specifics of how communities pursue regional coordination vary widely, and simply focusing on the economics of small systems to do so overlooks a key point: how utilities can more effectively function as essential community and economic partners and service providers.

The reasons for regionalization are numerous, driven by fiscal challenges, operational concerns, staffing shortages, regulatory compliance issues, and other difficulties that individual systems struggle to handle on their own. Smaller and disadvantaged communities face the most severe infrastructure risks amid declining populations and a lack of technical, managerial, and financial capacity. Cities such as Flint, Mich., and Jackson, Miss., have grabbed headlines in recent years, but rural places such as Knott County, Ky., and Luck, Wis., are also struggling to stay ahead of their existing infrastructure needs, let alone prepare for what’s to come. Decades of mounting infrastructure and economic pressures are compelling leaders to cobble together solutions wherever and however they can.

Despite an influx of federal funding over the last few years, including $58 billion from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and Inflation Reduction Act, the price tag for needed improvements keeps growing: $744 billion over the next couple decades according to Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates, in addition to costs associated with emerging contaminants and other evolving challenges. Proposed cuts to federal water infrastructure funding and financing programs are also looming.

These infrastructure concerns and economic realities have led to several salient considerations for policymakers, practitioners, and other leaders, including reasonable skepticism and concern about what regionalization might entail. Regionalization approaches have the potential to help all types of communities refocus on how they can improve economic, fiscal, and environmental outcomes more collectively, including for existing systems. The reality is there is no one-size-fits-all regional governance model that can be applied to the country’s drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater systems. Nonetheless, what follows are some baseline considerations that matter when thinking about regionalization as a way to advance infrastructure and economic development priorities together.

The status quo—of 50,000 public water systems nationally—is delivering inconsistently

America’s water infrastructure is highly fragmented and localized, with tens of thousands of systems withdrawing and treating or purchasing water and delivering it to end users. For instance, of the 50,000 community water systems, 90% of them (45,000-plus) provide water service to less than 20% of customers (or about 54 million of 300 million people). The concentration of these systems in smaller cities and towns means that these infrastructure considerations are closely intertwined with a complex set of community and economic development concerns over time as well. Meanwhile, there are more than 16,000 wastewater treatment plants, 2.2 million miles of clean drinking water pipes, and an assortment of other assets stretching across the country in service areas that frequently do not match jurisdictional boundaries.

This structural complexity, combined with the sector’s capital intensity, can make it challenging to manage regulatory pressures and technological change. Small systems lack the economies of scale to proactively address their infrastructure needs in terms of repairs and upgrades. Many systems may be unable to take on more debt for capital projects while also generating predictable and durable revenue, including, in some cases, from shrinking or low-income customer bases. The ability of water utilities to provide safe, reliable, and affordable service is not just a financial and operational concern, but also a key driver of economic growth. However, the small size and scope of many systems may limit the realization of this opportunity.

Regionalization does not always mean ownership consolidation

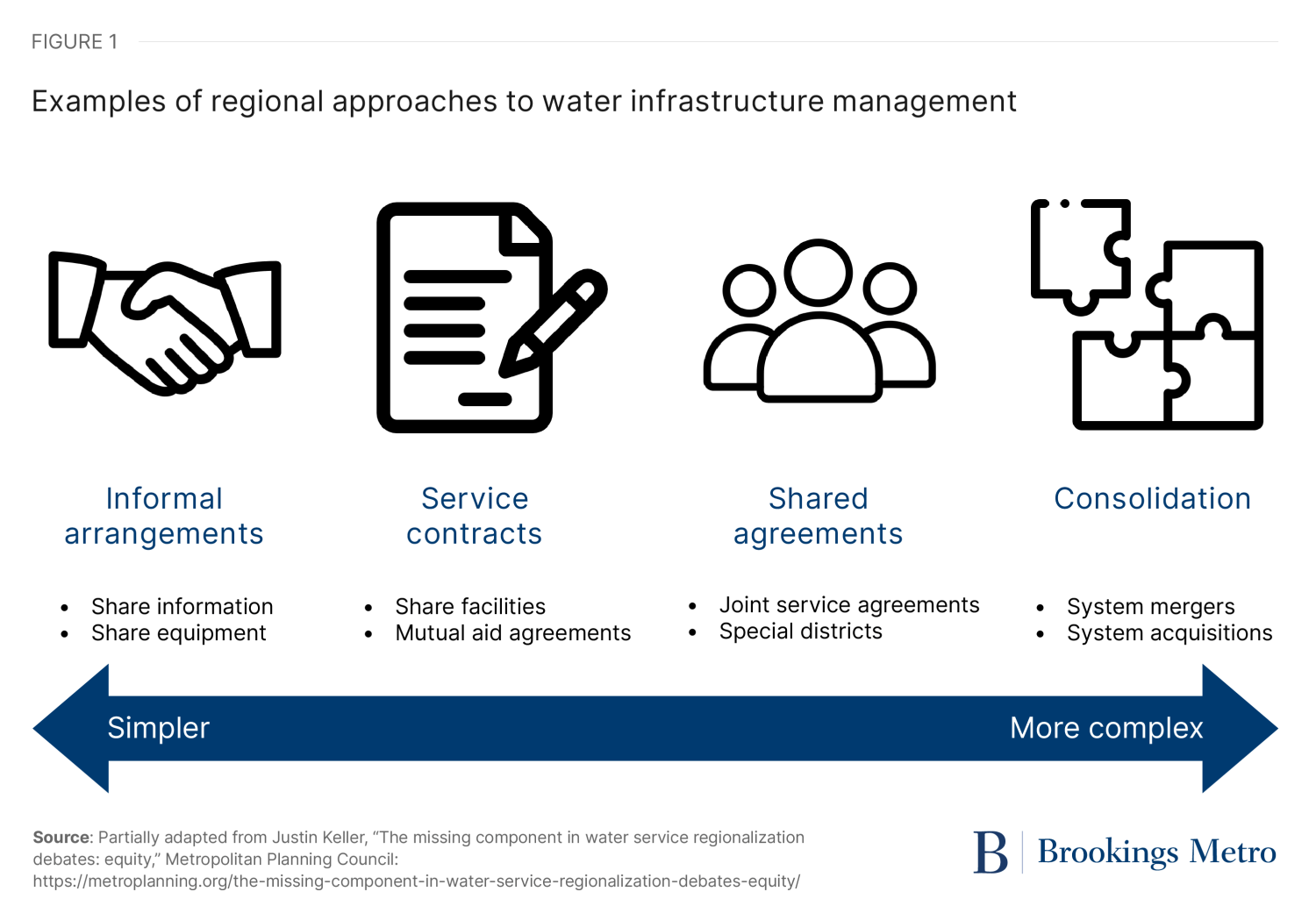

Consolidated ownership is just one form of regionalization. Utility collaborations and partnerships have emerged in different places for different reasons over time, and there is a spectrum of formal and informal ways in which communities—and their water systems—are collaborating to address their water infrastructure needs. From California and New Mexico to Kentucky and North Carolina, state and local leaders have developed a variety of regional plans and approaches aimed at boosting regulatory compliance, operational efficiency, and affordability. These can range from informal cooperation, such as sharing information or equipment, to public-public and public-private partnerships, to consolidation through mergers and acquisitions. Some systems may consider more intermediate options, including contracts to use facilities, mutual aid agreements, and other shared and joint service agreements.

The consideration of these regional approaches, however, is often lost amid concerns about ownership consolidation. For many local leaders who see their water systems as points of community pride and ownership, reasonable concerns around consolidation persist, including the potential role of private ownership or operation.

It is also essential for locally determined and community-led regionalization to be intentional about improving services to their traditionally underserved populations. The specific actors involved, timelines followed, and methods employed should be sensitive to social and economic equity. Federal agencies such as the EPA and Department of Agriculture have established additional guidance and technical assistance to support the various forms that regionalization can take. Other associations, industry groups, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and researchers have assessed or worked directly with communities on these issues. The key point is that regionalization comprises a broad umbrella of collaborative approaches.

Regional approaches to water infrastructure and services can promote broader economic development

Improving water infrastructure is not simply another engineering problem to solve or budget item to fix; investing in upgrades and leveraging the collaborative power of utilities also holds considerable promise for broader economic development opportunities.

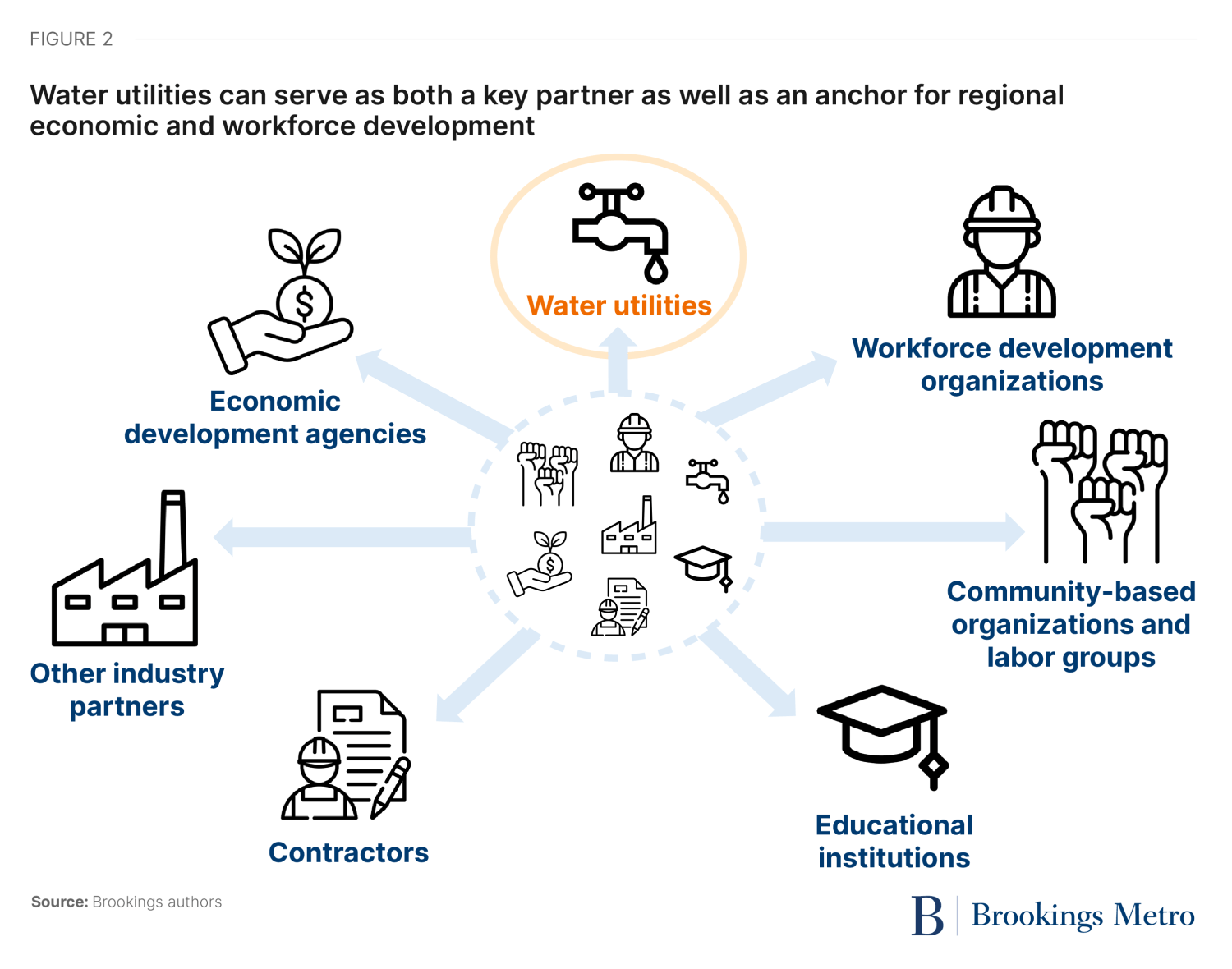

In many ways, water and other utilities can function as economic anchors for their communities by providing vital public services, training and employing local workers, and undertaking long-term capital investments. They serve as informal or formal hubs to bring together public and private partners. In some cases, they may be the driver for regional collaboration, in places such as Des Moines and the Lower Rio Grande in New Mexico. In other cases, they may be one part of a larger constellation of businesses and NGOs, as in Milwaukee’s water cluster. Partners still need to manage any potential downsides while balancing costs, but since water resources and services are so interconnected, a more comprehensive and integrated approach to community water management has increasingly driven new conversations, plans, and actions across the country.

More state and local leaders are viewing regionalization in terms of broader collaboration—drawing together water systems, economic development agencies, community-based organizations, and public and private entities. Fostering water’s ability to drive economic activity and innovation, as well as workforce development and more equitable and inclusive economic outcomes, are among the many areas where partnerships can play a role.

The emergence of sector partnerships—collaborations between educational institutions, workforce groups, and employers (such as water utilities)—presents a relevant way in which regional solutions have played a bigger role across the country. One of the more notable regional collaborations is BAYWORK, a coalition of Bay Area water utilities and other economic and community partners that has coordinated training, planning, and research to accelerate workforce development. The challenge and opportunity to address staffing shortages across the sector continue to drive many other regional efforts in places such as Camden, N.J., Saco, Maine, and Orem, Utah, where utilities have created new tables for community dialogue, established new professional networking opportunities, and tested new recruitment strategies.

Water utilities of scale offer a crucial economic foundation in terms of water resource management, strategic planning, and leadership, which could be extended on a regional basis to capacity-constrained providers.

Water utilities don’t need to go it alone

The country’s water infrastructure challenges are significant, and while individual communities and utilities are shouldering much of the responsibility, that does not mean they need to go it alone. A variety of new planning and investment approaches is emerging across the country, including regional solutions. The devil is in the details of who leads such regional collaborations—including how they are formed and for what purpose—but there is a spectrum of possibilities. A focus on mutually beneficial economic development should be chief among them.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Rethinking regionalization: Water utilities as economic development partners

July 8, 2025