Executive summary

The United States’ water infrastructure—including its drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater systems—faces enormous investment gaps. Leaking pipes, inefficient treatment plants, and other aging, vulnerable facilities not only require extensive upgrades, but are also contending with a variety of operational pressures due to a changing climate, an evolving economy, and more. As the primary owners and operators of this infrastructure, local water utilities bear most of these pressures, especially when it comes to planning and paying for improvements. But federal and state leaders also play a key role in regulatory oversight, programmatic coordination, and ongoing investment—heightened by the historic funding unlocked by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

State leaders in particular oversee a key conduit for water funding: State Revolving Funds (SRFs). These federally capitalized, state-led loan programs provide essential support for a range of clean water and drinking water projects across the country, including $43 billion appropriated via current federal infrastructure legislation. State agencies coordinate with local water utilities (and other eligible borrowers for SRF loans) to develop and implement plans—known as Intended Use Plans (IUPs)—and ultimately prioritize and assess how this funding is used across Clean Water SRFs (CWSRFs) and Drinking Water SRFs (DWSRFs). SRFs generally offer a low-cost and flexible option for local leaders to accelerate needed improvements.

However, despite the reach and impact of SRF funding, economic development officials, policymakers, and other stakeholders often do not understand how utilities access these funds and coordinate with states to prioritize projects. This confusion and uncertainty not only reduce the visibility of current water investments, but also potentially limit broader collaborations and community buy-in around future investments. That’s especially true when considering different climate- and equity-focused projects, including those that reduce flooding, promote water quality, and support affordability and access. Local utilities often have limited technical, financial, and staffing capacity to pursue such projects, making these broader collaborations all the more important and timely.

This report explores the nexus between state and local water funding to better understand various challenges around planning, project selection, and capacity in the current federal investment moment. It specifically examines the role of SRFs—particularly through IUPs and other materials—to illuminate whether and how state leaders are accelerating investments, often with notable gaps around climate and equity needs. It finds that:

- While many states spell out clear goals and identify a range of specific, needed projects as part of their annual water infrastructure planning efforts, they do not always prioritize climate or equity needs. For example, more than three-quarters of all states include some type of measurement and accountability around their IUP goals, but only about half explicitly include “green projects” in their goals, and only about a quarter describe environmental justice (EJ) concerns. Colorado and Washington are among the states that provide more extensive details on project timelines and other issues, including affordability and climate resilience.

- Many states do not cover the finer details when prioritizing and evaluating different water projects. Part of the challenge is that not all states—only about 47% of CWSRF and 61% of DWSRF programs—include project priority lists separately and publicly transparently from their IUPs. Exceptions include Kentucky and Indiana, which go into extensive detail on criteria to prioritize different green projects. In addition, despite notable gaps around equity projects, some states, including Pennsylvania and New Jersey, describe how they award points around related criteria in their project priority lists.

- A potential culprit: Constraints around fiscal, technical, and programmatic capacity are widespread and limit the ability of states and local utilities to proactively address needed water investments. For example, most states do not address local staffing needs to access and implement SRF funding. Less than 29% of states describe staffing needs in the short- and long-term goals within their IUPs, and less than 40% assess outstanding staffing needs in their annual reports. Alaska is among the states focusing on hiring additional program support and engineering staff to effectively implement SRF funding during the current federal moment.

Struggles to address such gaps hold back coordinated state and local action. As SRF program managers try to identify quality projects and creditworthy applicants, there may be structural barriers for many communities, including local utilities, to access funding where it is needed most. SRFs are not the only (or primary) vehicle to invest in the country’s water infrastructure needs, but they are a major piece of the funding puzzle. And the lack of equitable access to address pressing concerns—around climate challenges, for instance—is limiting investment across the country. However, this report reveals opportunities for federal, state, and local leaders to support greater capacity among utilities—particularly around staffing and technical assistance—to address such gaps.

Understanding the nation's water investment challenge

Federal, state, and local leaders share several different responsibilities for overseeing the country’s water infrastructure: providing drinking water, handling wastewater, managing stormwater, and more. Yet they are increasingly struggling to plan and pay for improvements. From plants and pipes to lakes and rivers, the country’s humanmade and natural systems face a variety of challenges. Many water systems are aging and physically vulnerable, resulting in widespread leaks, bursts, and other quality and reliability concerns. A more extreme and unpredictable climate is causing floods, droughts, and other risks for these systems. Meanwhile, many communities and households cannot afford or access safe, clean water—evident in cities such as Flint, Mich. and Jackson, Miss., but also in many other regions.

Underlying all these challenges are enormous investment gaps. Keeping up with needed water upgrades requires considerable public and private investment at a national, state, and local level. Recent estimates from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—the primary federal agency responsible for water infrastructure oversight—show that $744 billion will be needed to address drinking water and wastewater improvements over the next 20 years. Whether it’s fixing pipes, modernizing treatment plants, or conserving and protecting natural resources, the list of water needs keeps growing, as does the price tag. And with more than 2.2 million miles of pipes, 16,000 treatment plants, and 250,000 rivers stretching 3 million miles, the geographic scale of needed projects is huge.

However, increased federal funding—especially from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)—is helping fill these gaps. From those two laws, about $58 billion over five years is going toward water infrastructure, including billions to replace lead service lines, reduce emerging contaminants, and accelerate an assortment of other climate-related and technological upgrades. Nominally, this total represents the single largest federal water infrastructure investment ever, much of which is being channeled through existing grant and loan programs the EPA oversees. The Drinking Water and Clean Water State Revolving Funds—or the DWSRFs and CWSRFs, respectively—are the primary vehicles to move this combined $43 billion in funding to different projects across the country. (Box 1 at the end of this section offers more context on SRFs, including their programmatic history and design.)

But even as there is heightened interest in this funding, there is still widespread confusion about how it flows, why the revolving funds prioritize certain projects, and when and where those funds make a difference. That’s especially the case for everyday citizens, economic development leaders, and other stakeholders advocating for additional water infrastructure investment at a state and local level.

Part of this confusion stems from a lack of understanding on how state and local water funding works, particularly around planning and project selection. While federal funding from the IIJA and IRA is historic and provides a needed jolt for the country’s water infrastructure, it still only addresses a fraction of the country’s total investment needs—and the responsibility to develop and implement plans, capital upgrades, and other daily operational improvements still largely falls on the shoulders of individual water utilities. The reality is that states and localities (especially the latter) are the primary owners, operators, and investors in the country’s water infrastructure.

More than 50,000 water systems are scattered across the country, varying widely in their geographic reach, customer base, and infrastructure assets. Some systems may only serve a few hundred households in a rural county, for instance, while others may serve hundreds of thousands—among other commercial and industrial customers—in large metropolitan markets. Moreover, some systems may only oversee drinking water, while others may oversee wastewater and stormwater needs too. Most water utilities (88%) are publicly owned and typically nested under a local government, but there are also several private- or investor-owned utilities that have sizable footprints. The result is a highly fragmented, localized set of water actors responsible for driving investment.

States also vary widely in their specific infrastructure concerns and priorities. For example, California, Arizona, and other states in the West may be more focused on concerns around water scarcity and demand, while Michigan, Illinois, and other states in the Midwest may be more focused on water quality and aging assets. Despite these differences, states tend to serve as important water regulators and policy setters, coordinating programmatic oversight with the EPA and other federal agencies. State departments involved in environmental management, natural resource conservation, or public health are generally responsible for overseeing utility compliance with federal laws, such as the Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act. They also develop larger statewide water plans to guide short- and long-term policy objectives, in addition to being involved in the allocation of different federal and state funding resources via Intended Use Plans (IUPs), described in Box 1 below.

In this way, local water utilities, alongside state partners, must navigate a complex set of operational, regulatory, and investment concerns. And they often must do so with dwindling federal funding, despite the current influx of support from the IIJA and IRA. Historically, states and localities have accounted for more than three-quarters of annual public spending on water infrastructure according to the most recent estimates available. Following a spike in federal funding during 1970s that coincided with the passage of the Clean Water Act and Safe Drinking Water Act, federal support has since come in the form of capitalizing SRFs—state-led water loan programs amounting to roughly $2.5 billion each year.

The financial pressure facing local water utilities is especially extreme. Census Bureau surveys on state and local government finances show that these local utilities make up 98% and 99% of direct spending on sewerage and water supply, respectively, compared to their state counterparts. In turn, water utilities tend to rely most extensively on their own-source revenues to keep up with growing operational, maintenance, and capital costs, particularly through volumetric rates and other fixed fees for customers. However, despite these fees increasing across the country, they still struggle to keep up with the level of investment needed. The result is utilities taking on more debt, testing new financing tools (e.g., green bonds and stormwater fees), and grappling with broader customer affordability concerns.

While some utilities benefit from a stable (or growing) customer base and generate durable revenues, most are struggling to keep up with all those escalating investment needs—from repairs to regulatory compliance needs to climate pressures—and continue to call for more federal and state support. Yet even if extra support came, many lack the programmatic flexibility to proactively address their needs. A wave of retirement and recruitment challenges continue to vex many utilities, leading to widespread staffing shortages. Integrating new technologies and pinpointing emerging needs is not always fast or easy. Federal and state funding, including through SRFs, often have local match and reporting requirements that utilities may not always be able to meet, speaking to their tight budgets. Ultimately, a lack of local fiscal and technical capacity remains a challenge across the country.

States, in turn, are often an understudied funnel point in water infrastructure planning and investment. Local utilities own the systems and easily spend the largest amounts; federal agencies set regulations and are currently investing considerable amounts; and state agencies often bridge these gaps. Each state is left to make enormous decisions, including how and where they spend federal money, their lending approach, if they spend their own money, and if they prioritize other evolving goals around climate and equity in the communities that need investment.

This report explores the nexus between state and local water funding to better understand these various challenges around planning, project selection, and capacity in the current federal investment moment. It specifically examines the role of SRFs—a primary vehicle of water funding—to illuminate whether and how state leaders are accelerating investments. The report reveals opportunities for federal, state, and local leaders to support greater capacity for local utilities, particularly around staffing and technical assistance, to address such gaps.

Box 1. Exploring how State Revolving Funds work

State Revolving Funds (SRFs) act as key levers for water investment across the country. As federally capitalized, state-led water loan programs, SRFs provide financial assistance for clean water and drinking water, helping water systems and states meet health protection objectives and supporting various infrastructure improvement projects. Each year, Congress appropriates roughly $2.5 billion to the EPA to allocate this funding as capitalization grants to all 50 states and Puerto Rico, with states required to provide a 20% match to the federal dollars they receive.

SRFs were established by their respective acts, with the CWSRF created by the 1987 amendments to the Clean Water Act (CWA) and the DWSRF created by the 1996 amendments to the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). Prior to the passage of these acts, construction grants and wastewater grants were the primary sources of federal funding for the nation’s water infrastructure projects. With the amendments authorizing funding through SRFs, states now have significant discretion in project selection and fund distribution, enabling them to address local priorities while advancing health and environmental goals.

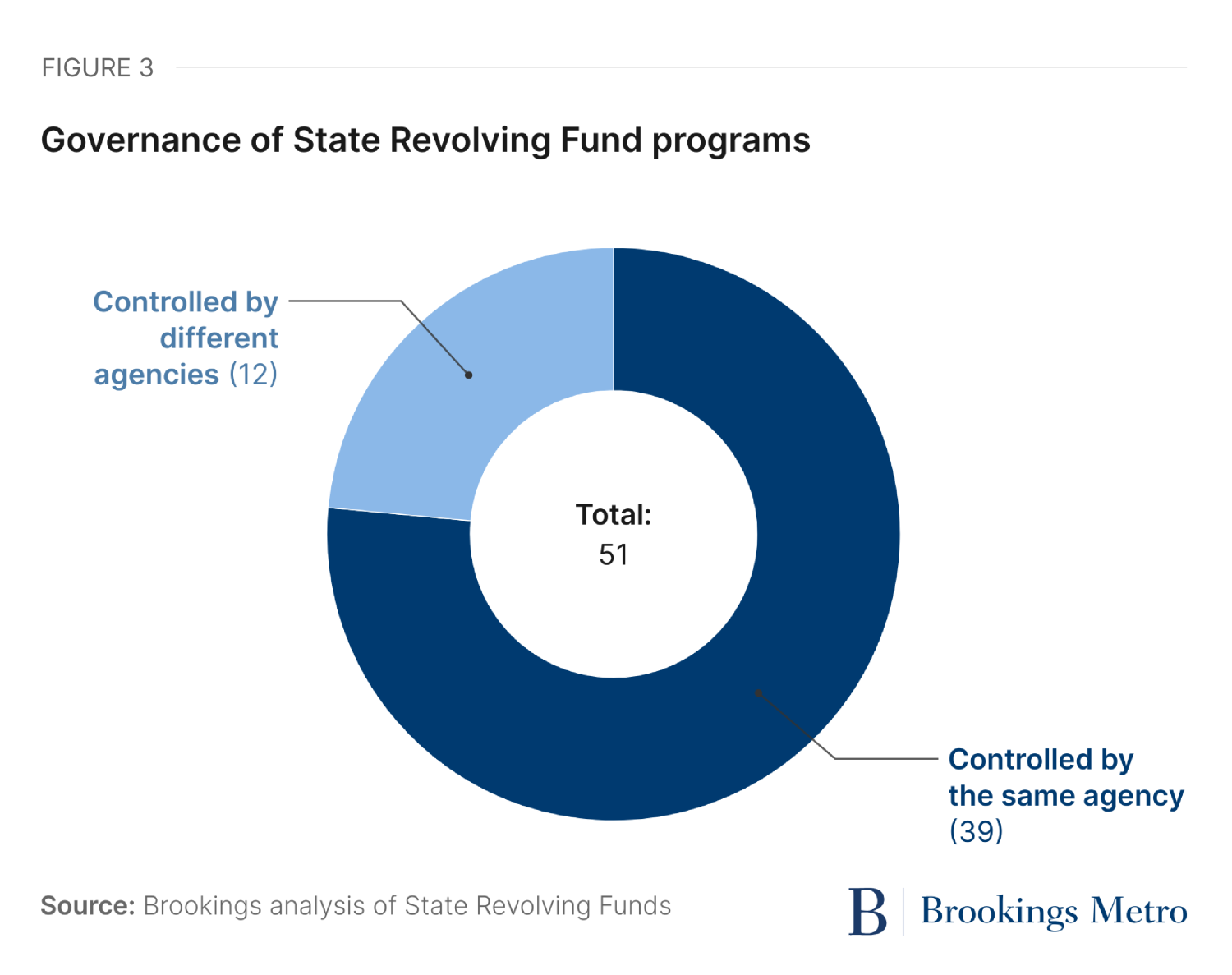

Oversight of SRF funds varies by state. In most cases, a state’s environmental or natural resources agency manages the funds. Some states, including Pennsylvania, rely on separate entities (or financing authorities) to administer SRF programs. However, in about a quarter of states, responsibility is split between two agencies, such as the Department of Environmental Quality overseeing clean water projects and the Department of Health managing drinking water programs.

Clean water: The CWSRF offers financial support to communities, private entities, and nonprofit organizations for projects, including the construction of municipal wastewater facilities, the control of nonpoint source pollution, and the development of decentralized wastewater treatment systems. As of 2023, the program has provided $172 billion in funding for water quality infrastructure projects through more than 48,000 loan agreements. In addition to its standard loans, the CWSRF offers additional subsidies and focuses on critical green infrastructure, water and energy efficiency improvements, and other environmentally innovative activities through the Green Project Reserve.

Drinking water: The DWSRF provides funding to both publicly and privately owned community water systems—as well as nonprofit, noncommunity water systems—for projects aimed at improving drinking water treatment, repairing pipes, enhancing water supply sources, and more. Since 1997, states have leveraged $24.5 billion through over 18,000 loans to repair, replace, and construct vital water infrastructure. States have the flexibility to determine which projects receive funding, provided they adhere to SDWA requirements. Priority must be given to projects that address the most serious risks to human health, ensure compliance with the SDWA, and assist systems most in need.

As a condition of receiving SRF funds, states must annually prepare an Intended Use Plan (IUP) outlining how they intend to use the funds and meet program objectives. The IUP must also include the state’s criteria and method for distributing funds. While these criteria and methods differ across states, all are required to define “disadvantaged communities” and establish affordability criteria to allocate additional subsidies. This affordability criteria are just one factor in project selection, alongside the ranking systems states develop to prioritize their unique needs. Each state’s ranking system guides the projects placed on its project priority list—a list of proposed projects seeking funding (or expecting to close out loans) for that year. At the end of the fiscal year, states must submit an annual report to the EPA detailing how they met the SRF goals and objectives in the previous year’s plan.

Current dynamics and looking forward

While SRFs represent a relatively small share of overall water infrastructure funding, they play a crucial role in the planning, project selection, and investment process. State leaders depend on SRFs to prioritize projects and leverage additional funding, ensuring that different communities can access needed resources to replace and address existing infrastructure, in addition to considering new improvements. However, questions persist about whether these funds are sufficient to meet the nation’s water infrastructure needs moving forward, especially as emerging challenges such as drought and extreme heat, driven by climate change, place additional strain on systems. Compounding these concerns, states and local utilities are grappling with programmatic and other capacity issues to fully utilize available funding; for instance, $9.6 billion in SRF funds is yet to be committed to projects in the current federal infrastructure moment. This amount of unspent dollars raises critical questions about where states are encountering barriers in directing water infrastructure funding to the communities that need it most.

Methods

By focusing on the SRF programs, this report aims to shed light on a key conduit for water funding and closely examine how different state agencies prioritize, allocate, and evaluate water funding. Doing so can help a broader set of stakeholders—including everyday citizens, economic development leaders, and policymakers not steeped in infrastructure knowledge—build greater awareness around how infrastructure improvement planning works, both during the current federal moment and beyond.

In particular, this report examines which state entities govern and control flows of water funding via SRFs, and how they prioritize and assess the use of this funding. We not only focus on funding for traditional gray infrastructure systems (e.g., drinking water, wastewater), but also consider funding for a broader range of green infrastructure improvements (e.g., rain gardens) and equity-focused initiatives (e.g., household affordability, household access to clean water). To be sure, funding for water infrastructure improvements comes from a variety of sources, particularly local revenue sources, including variable rates and fixed fees (e.g., connection charges) overseen by individual utilities. But state water infrastructure funding tends to come in the form of grants or loans from SRFs, which serve as the primary area of analysis for this work.

We examine a common set of questions across all 50 states (and Puerto Rico) to analyze the drinking water and clean water SRFs, specifically by considering relevant planning and prioritization documents such as Intended Use Plans (IUPs), annual reports, and other publicly available content available from state agencies. These documents contain essential (and sometimes federally required) details to guide state-level water policies, programmatic needs, and project priority lists; this is especially the case for IUPs, which describe how states intend to use SRF funding as part of applications for federal capitalization grants. To get a full scope of needed water investments, we examine the most currently available documents across both CWSRFs and DWSRFs.

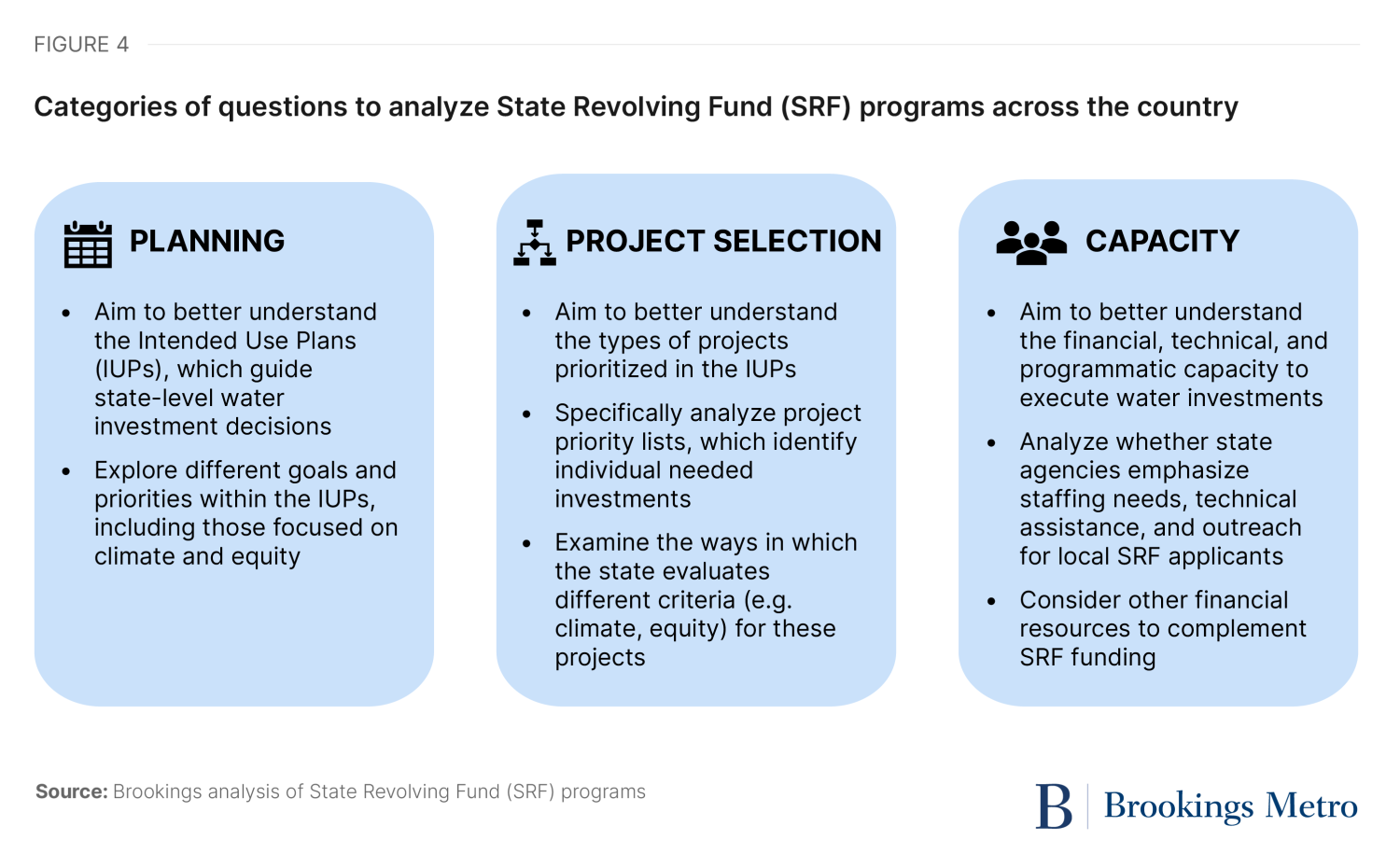

Our schema includes a total of 21 questions organized into three categories (spelled out below). The first six questions focus on planning, including information on state-level goal-setting and policy priorities, typically found in IUPs. The next six questions focus on project selection, including information on state project priority lists and the criteria used to rank different projects, typically found within or alongside IUPs. The final nine questions focus on capacity, including information on staffing, technical assistance, community outreach, and other state financial resources and programmatic flexibility to help local utilities access SRF funding; these details appear across a broader range of sources, such as annual reports and materials available on state agency websites.

Several previous analyses on SRFs have come out in recent years addressing similar planning, project selection, and capacity needs, including from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Duke University’s Nicholas Institute, and the EPA’s Office of Inspector General, among others. Our goal is to complement these analyses by probing a specific set of questions across different states, including an emphasis on climate- and equity-focused efforts—two primary areas of attention for federal, state, and local leaders during the current federal moment. “Climate” efforts include policies, programs, or projects linked to environmental justice and green infrastructure concerns, while “equity-focused” efforts include policies, programs, or projects that center around disadvantaged communities, per EPA definitions. A list of these and other key terms is available below.

A more detailed version of this methodology, including a full list of questions, is available in a downloadable appendix.

-

Key terms

Disadvantaged communities: Communities that experience or are at risk of experiencing disproportionally high exposure to pollution, whether in air, land, or water. Per federal requirements, these communities also demonstrate water affordability concerns, including income, unemployment, population trends, and economic distress.

Environmental justice: The fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

Green projects: Projects that address green infrastructure, water efficiency, energy efficiency, and environmentally innovative activities, which can embody both climate mitigation and adaptation approaches:

- Green infrastructure includes practices that maintain and restore natural hydrology, maintain floodplains/wetlands, and reduce impervious surfaces.

- Water efficiency includes improving technologies and practices for water delivery that use less water, including conservation and reuse efforts. They can also include water audit and conservation plans.

- Energy efficiency includes improving technologies and practices that reduce energy consumption and/or produce/use renewable energy.

- Environmentally innovative activities include novel approaches to delivering services or sustainably managing water resources. These activities can relate to both climate mitigation (focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions) and climate adaptation (focused on withstanding current and future climate impacts, such as floods, and building greater resilience).

Community outreach: Efforts to engage and involve communities in the environmental decisionmaking process and foster communication between state agencies and the public. The goal is to ensure that all community members, including those from vulnerable and underserved populations, can participate meaningfully and are informed about the water issues that affect them. Key components include engagement initiatives, public participation plans, and opportunities for public comment.

Technical assistance: Refers to support provided to individuals, utilities, or organizations to enhance their ability to understand and address environmental issues. This support can come in various forms, including providing expertise and resources, helping with project implementation, and building capacity to manage environmental challenges.

Staffing needs: The number and types of personnel required to effectively carry out the agency’s mission and responsibilities. This includes assessing the workload, skills, and expertise necessary to address the agency’s environmental protection goals, manage regulatory requirements, and implement new programs and initiatives.

Findings

1. While many states spell out clear goals and identify a range of specific, needed projects as part of their annual water infrastructure planning efforts, they do not always prioritize climate or equity needs.

As part of their Intended Use Plans (IUPs), state agencies are required to lay out several overarching goals to guide water policies and plans for clean water and drinking water investments. Moreover, within their annual reports, state agencies relate these goals to ongoing investment, including progress on particular projects. However, the level of detail around these goals in both IUPs and annual reports can vary widely, particularly when it comes to climate and equity needs. Results from the following six planning-related questions reveal this widespread variation across different SRF programs.

Where states tend to spell out more details is around identifying short- and long-term goals in their IUPs, while also regularly monitoring progress in achieving those goals within their annual reports. More than three-quarters of all states include some type of measurement and accountability around their goals. For example, Oklahoma describes several accomplishments in the CWSRF annual report around both short- and long-term goals, such as improving data entry, ensuring more loans reach smaller communities (those with populations under 10,000), and maintaining and developing relationships with other state agencies. Similarly, in its DWSRF annual report, Delaware visualizes how it made specific progress on improving financial stability across the state through a cash flow model, provided technical assistance and training to different communities, and implemented a new interest rate and affordability policy.

States also prioritize a clear list of projects in line with these goals. Nearly 90% have clear aggregations of previously or currently funded SRF projects as part of their annual reports. In its CWSRF annual report, Colorado includes extensive detail on active and forgiven loans, including borrowers, as well as the loan date, amount, term, interest rate, funding source, and more. This information covers loans across all types of projects going back to 2009.

However, climate- and equity-focused goals can sometimes be missing, and the timelines to execute on and operationalize approaches to meet these goals are often vague. Averaged across the CWSRFs and DWSRFs, only about half of states explicitly include “green projects” in their goals, and only about one-quarter describe environmental justice (EJ) concerns. In addition, less than 20% of states include more detailed timelines for their goals (e.g., “five to 10 years” versus “short and long term”). Many states, ranging from Connecticut to Montana, do not include any clear timelines, green projects, or EJ goals. Among the exceptions is Washington, which includes multiple sub-bullets and details on goals around affordability and climate resilience in its DWSRF IUP. On the former, these details include acknowledging and addressing household affordability constraints, in addition to noting the percentage of funding to assist disadvantaged communities. On the latter, details include updating existing plan guidance to require resilience criteria for ongoing projects.

2. Many states do not cover the finer details when prioritizing and evaluating different water projects.

Most states do not expose how staff evaluate projects. Part of the challenge is that not all states—only about 47% of CWSRF and 61% of DWSRF programs—include project priority lists separately and publicly transparently from their IUPs. And even if they do, the details can be lacking. While states are federally required to identify and prioritize projects that pose significant health and environmental risks, that does not mean states include precise metrics or other clear criteria in their project priority lists. For instance, less than 10% of states include a detailed breakdown of their scores to prioritize different projects. New Hampshire’s project priority list describes the amount of points each project received for aging infrastructure and protecting water quality and public health. Yet most states, stretching from Vermont to Illinois, do not provide such details.

Widespread gaps are evident in how states prioritize climate-focused projects. A little over half (58%) of states include green projects as part of ranking criteria in their CWSRF project priority lists, and a little over a third (37%) do so in DWSRF project priority lists. States also do not consistently describe the specific amount of “green contributions” for each project, or the amount of funding that comes from the SRF’s Green Project Reserve—a federally required amount of funding states need to dedicate to green projects (see Box 2 below). In Georgia and Wisconsin, for instance, CWSRF project priority lists do not show green contributions for different projects. Exceptions include Kentucky’s CWSRF IUP, which goes into extensive detail on criteria to prioritize different green projects; and Indiana’s DWSRF project priority list, which is not only publicly and transparently accessible beyond the IUP, but also notes the Green Project Reserve category for each project.

Most states also fail to use disadvantaged neighborhood designations when evaluating projects, demonstrating clear gaps around equity needs. Only about a third of states clearly indicate if a project serves a disadvantaged community across their CWSRF and DWSRF project priority lists, and less than 14% include specific criteria on EJ concerns. Idaho and Louisiana are among the states that include several details in their DWSRF project priority lists—on the scope of projects supported, the population served, and more—but do not indicate any clear connection to disadvantaged communities. On the other hand, Pennsylvania and New Jersey, among others, provide more context on equity-focused projects, including awarding points in their project priority lists if those projects are located in an EJ community.

Box 2: Understanding the Green Project Reserve

The Green Project Reserve (GPR) was established in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 to ensure that a portion of each state’s CWSRF and DWSRF program is directed toward environmentally beneficial projects. Specifically, GPR funds focus on projects that support green infrastructure, improvements in water and energy efficiency, and other environmentally innovative activities. In a 2012 adjustment, the ARRA mandated that states must allocate no less than 10% of their CWSRF to these green projects, while DWSRF set-asides may be used to support similar efforts. Through the GPR, Congress aims to guide water utilities—through the states—toward practices that reduce their environmental impact, promote water and energy conservation, and enhance climate resilience.

States play a key role implementing the GPR by identifying which projects qualify and ensuring they align with program goals. To assist in the process, states can refer to the EPA’s technical guidance, which helps them assess GPR eligibility and prioritize certain projects. For example, in Indiana, the state’s criteria for both CWSRF and DWSRF programs award points to projects that incorporate sustainable infrastructure elements as identified on the GPR. In some instances, such as Kansas, the state will indicate the amount of GPR funding a project is estimated to receive on their project priority list.

By fostering these green initiatives, states are setting a precedent in sustainable practices, conserving water and energy resources, and addressing water quality priorities. Some states, including Mississippi and Alabama, have not received enough green project proposals to fully allocate GPR funds. However, these states continue to solicit GPR-eligible projects, helping utilities take advantage of opportunities to implement sustainable infrastructure.

3. A potential culprit: Constraints around fiscal, technical, and programmatic capacity are widespread and limit the ability of states and local utilities to proactively address needed water investments.

Local utilities face a variety of capacity constraints in keeping up with existing water needs, let alone pursuing new, more ambitious water investments. Results from the following nine capacity-related questions show how SRF programs do not often consider challenges around staffing, technical assistance, or other financial resources that help utilities access funding and accelerate needed improvements.

Admittedly, many states recognize the need for community outreach and technical assistance to help potential borrowers (namely, local water utilities) access SRF funding. Within their CWSRF and DWSRF IUPs, up to 80% of states describe community outreach efforts to reach local utilities. And up to 84% emphasize technical assistance efforts, including grants and other predevelopment support for projects. Still, 43% of states lack a public and transparent dedicated website for technical assistance, limiting information exchange and awareness. In turn, outreach in states come in many forms, from South Carolina targeting borrowers through emailing and contacting trade associations to Nevada educating water systems on available funding, and Arkansas and Colorado staffing booths at numerous conferences and conventions.

Most states also do not address local staffing needs to access and implement SRF funding. Less than 29% of states describe staffing needs in the short- and long-term goals within their IUPs, and less than 40% assess outstanding staffing needs in their annual reports. For instance, West Virginia’s CWSRF IUP and annual report do not mention staffing considerations as part of the state’s goals or discuss how it is addressing them, even though the state notes how retirements and other workforce development challenges are pressuring utilities. Likewise, Michigan’s CWSRF IUP identifies a need to hire and train new staff, but the state’s annual report does not describe any accomplishments or milestones around closing these gaps. Alaska is among the states addressing these staffing needs head-on; the state’s CWSRF IUP establishes a goal to hire additional program support and engineering staff to effectively implement SRF funding during the current federal moment.

There can also be a lack of other dedicated state funding separate from SRFs, especially to help with climate- or equity-focused projects. Less than one-quarter of states have a separate pot of funding focusing on customer affordability. Likewise, less than 16% of states have separate funding for green projects beyond SRFs. For instance, South Dakota notes green funding eligibilities related to SRF funding on state agency webpages, but it does not identify any other separate green funding opportunities. Iowa provides a socioeconomic assessment sheet for utilities to report community attributes such as poverty rate and labor force participation, but it does not offer grants or loans beyond the SRF based on these results. Still, exceptions exist for climate- and equity-focused funding, including Rhode Island’s Ocean State Climate Adaptation and Resilience (OSCAR) fund and Oregon’s Sustainable Infrastructure Planning Projects (SIPP) funding.

Implications and recommendations

Amid a historic surge in federal infrastructure funding, states and local water utilities continue to face several planning, project selection, and capacity challenges. Although states and SRFs only account for a small slice of the total water funding landscape in the U.S., they are important partners (and parts) to getting more investments done across different communities. Getting funding out the door nimbly and efficiently while targeting needed investments around improved climate and equity outcomes represents a key challenge and opportunity for the country.

The federally required IUPs and annual reports that help guide and assess SRF funding reveal gaps in how states are channeling resources to local water utilities. While these key planning documents do not capture every single dimension of state water policy or other various efforts emerging across the country to accelerate climate mitigation and adaptation, equity, technological innovation, and more, they still illustrate several shortfalls in programmatic coordination and implementation.

States are developing short- and long-term goals in their IUPs that touch on community outreach and signal a need for greater accountability and measurement (also reflected in their annual reports), but the precise timelines to execute on these goals are not typically clear, nor are stated objectives around accelerating climate- and equity-focused projects. The specific criteria states use to rank and prioritize needed projects are not always clear, and their project priority lists do not always specify how EJ concerns and disadvantaged communities relate to current or previous investments. Lastly, states may acknowledge significant staffing, technical, and financial constraints (especially among local water utilities), but their IUPs and annual reports do not address these capacity challenges head-on in many cases, outside of their stated goals and other existing technical assistance efforts.

Struggles to address such gaps hold back coordinated state and local action both during the current federal moment and in the decades to come. As SRF program managers try to identify quality projects and creditworthy applicants, there may be structural barriers for many communities, including local utilities, to access funding where it is needed most. Again, SRFs are not going to solve all of the country’s various water investment needs, but they are a major piece of the funding puzzle. And the lack of equitable access to address pressing concerns—around climate challenges, for instance—is limiting investment across the country.

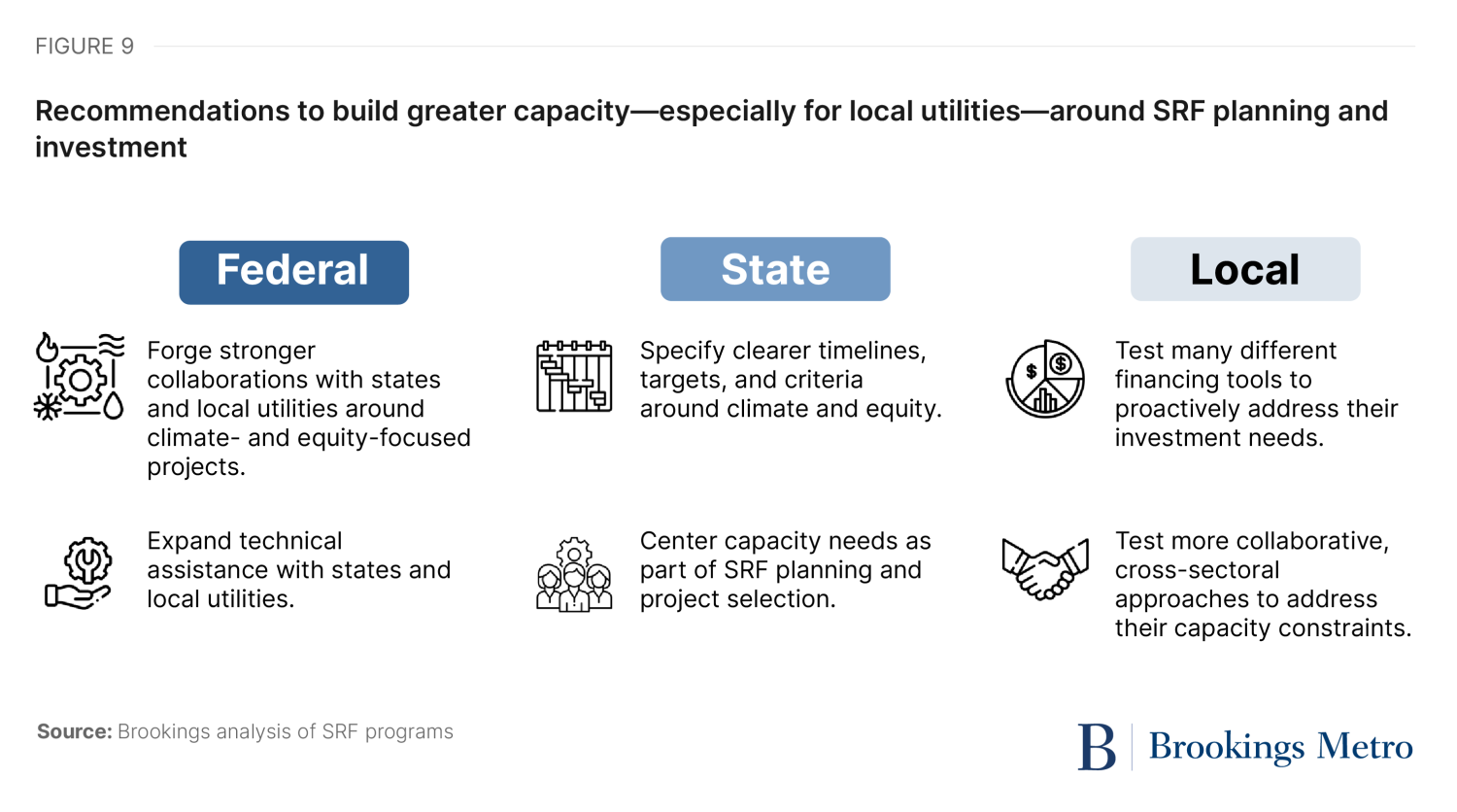

Federal, state, and local leaders should collectively respond in several ways to enhance capacity (for utilities especially) and ultimately promote greater water investment:

Federal leaders, especially the EPA, need to provide more technical assistance to states and local utilities, particularly by providing guidance around different financial indicators and climate needs. Doing so can make it easier for local utilities especially to access funding. As part of the rollout of IIJA funding, the EPA and other federal agencies have already been stressing additional technical assistance, including the development of new information resources and outreach efforts. But the durability of these efforts is essential and cannot sunset once the IIJA funding dries up after the next couple years. Past GAO assessments, for instance, have stressed the need for the EPA to work closely with states on improving information around different financial indicators (e.g., future lending capacity, interest earnings, etc.) to guide the long-term financial health and performance of SRFs. The GAO has also recently called on the EPA to help states improve their data collection efforts and better predict estimated costs around future climate investment needs as part of their CWSRF programs.

Federal leaders, including the EPA and other agency partners, need to forge stronger collaborations with states and local utilities around climate- and equity-focused projects, including greater accountability, measurement, and investment around disadvantaged communities and workforce development with SRF funding. Executive orders from the Biden administration have stressed EJ issues and workforce needs, and technical memoranda from the EPA and other agencies (including the Department of Labor) have encouraged states to invest more in these needs. These come on top of broader federal initiatives, including Justice40, that aim to better define, measure, and connect funding to disadvantaged communities. However, even with this guidance, many states continue to follow business-as-usual practices with their SRF plans and project selection; EPA Office of Inspector General assessments have found that most states still do not include climate resilience needs in their IUPs, and previous Brookings research has highlighted state struggles to connect infrastructure funding with proactive workforce development. The EPA, Labor Department, and other federal partners need to better quantify and assess what states are doing with expanded SRF funding around such climate and equity needs, and lead ongoing discussions with states on how to better integrate these considerations in their IUPs and annual reporting.

State agencies responsible for SRF planning and project selection need to specify clearer timelines, targets, and criteria around climate and equity needs. As states oversee increased SRF funding in the coming years, they have an opportunity to encourage green projects beyond prevailing minimum federal requirements. The same is true for projects focused on disadvantaged communities. States also have a chance to precisely track how and where IIJA funding is going to support climate and equity objectives. For instance, when directing funding to lead service line replacements, Wisconsin has established equity prioritization plans, and Pennsylvania has loosened regulations to make it easier to invest on private properties. North Carolina and Louisiana have similarly articulated the types of projects benefiting from expanded SRF funding, including green projects, as part of their project priority lists—which may offer precedent for monitoring and assessment over time.

State agencies also need to center capacity needs—for local utilities in particular—as part of SRF planning and project selection. Many states already offer technical assistance (TA) and engage in community outreach to help local water utilities apply for and access SRF funding, and there are opportunities to extend the reach of these efforts through publicly accessible and transparent TA webpages and targeted engagement in disadvantaged communities. Improved administrative practices, such as expanded staffing and training around cash flow modeling, can also help local utilities build greater technical knowledge and capacity. Similar to federal agencies, these state agencies can coordinate with other departments (e.g., labor, economic development) to center workforce development as an actionable priority as well. For example, the Texas CFO to GO Program provides financial consultations for local utilities to help with financial reporting, regulatory compliance, and other operational processes. And as part of its High Road Training Partnership, California has centered water workforce needs across a range of utility, association, and other partners, and established a State Advisory Council; while not directly connected to SRF funding, such efforts have spillover benefits for project planning and execution.

Local leaders, particularly water utilities, need to test many different financing tools to proactively address their investment needs, with an eye toward climate- and equity-focused projects. SRF funding by itself is not a substitute for the variable rates, fixed fees, and other revenue sources that local water utilities predominantly rely on for their operational and capital needs. Utilities of all sizes and geographies face constrained budgets, hefty debt loads, and other financial headwinds, which should compel them to not only consider a range of funding and financing strategies, but also improve their underlying asset management and budgetary processes to integrate new technologies, designs, and project considerations. For example, San Francisco’s Sewer System Improvement Program illustrates how utilities are integrating new performance metrics, contracting opportunities, and climate and equity considerations into project planning and implementation. Philadelphia’s Green City, Clean Waters effort similarly represents a short- and long-term approach that seeks to comprehensively address a combination of stormwater, climate, and equity needs, while considering other incentives, fees, and revenue sources. Even communities with traditionally lower fiscal capacity and economic struggles, such as Chester, Penn. and Prince George’s County, Md., have experimented with new climate- and equity-driven financing strategies in response to pressing environmental compliance needs and system upgrades.

State and local leaders, including water utilities and other community partners, need to test more collaborative, cross-sectoral approaches to address their capacity constraints. Utilities are balancing multiple competing pressures—financially and otherwise—that limit their ability to test new approaches or integrate climate and equity considerations into how they get projects done. Workforce development is one area where utilities should actively work with training providers, educational institutions, community-based organizations, labor groups, and other partners to invest in ongoing skills development, alongside recruitment and retention strategies. Flexibilities and eligibilities to use SRF funding for workforce development should factor into such efforts (as the EPA and other federal agencies have previously encouraged), but ultimately, local leaders need to center workforce development as a strategic priority in ongoing water investments—not as an afterthought. There are multiple examples of utilities and other local partners addressing these workforce needs; the Water to Work Internship Program in Grand Rapids, Mich., for instance, demonstrates how employers are working with a community college to boost visibility around water careers and equip prospective workers with needed experience and credentials.

Conclusion

Federal funding from the IIJA and IRA represents a historic shift in support for water investment nationally, but the flow and ultimate impact of this funding depend on many state- and locally led policies, programs, and processes. The clean water and drinking water SRF programs are the established conduits for this funding—and will continue to guide support once these laws expire.

But as this report has shown, SRF planning and project selection processes do not always adhere to the clearest goals, timelines, or targets to maximize the implementation of this funding, especially for climate- and equity-focused projects. Constraints around fiscal, technical, and staffing capacity are a continued challenge for state and local leaders to accelerate water investment in these laws (and more generally), which the SRF programs do not typically articulate or address.

However, some states are spelling out clearer goals and objectives, quantifying and evaluating project impacts, testing new financing tools and community collaborations, and executing on a variety of other efforts to accelerate water investment. Many of these efforts appear in IUPs, annual reports, and related materials, but they also stretch far beyond SRFs. No single plan or program will solve the country’s various water needs; a combination of different state- and locally led plans and innovations are chipping away at the water challenges utilities and communities face. Ongoing experimentation and accountability are essential to build momentum in years to come, and the current federal moment represents an important starting point to unlock more widespread investment nationally.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors are grateful for thoughtful comments from the multiple experts and practitioners who provided feedback for this report. The authors are especially thankful to the individuals who provided thoughtful comments on an earlier draft, including Newsha Ajami, Robert Puentes, Shalini Vajjhala, Benjamin Swedberg, and Adie Tomer, as well as several members of the U.S. Water Alliance team. The authors also would like to thank Michael Gaynor for editing, Alec Friedhoff for data interactive coding, Carie Muscatello for her web and print design, and the rest of the Brookings Metro communications team for their support. All remaining errors and omissions are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Brookings Metro would like to thank the Kresge Foundation for their generous support of this analysis. Brookings Metro is also grateful to the Metropolitan Council, a network of business, civic, and philanthropic leaders who are both financial and intellectual partners of the Program.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).