Consider the following fictional scenario: Mayor Joe’s cash-strapped city is facing substantial challenges thanks to increasingly extreme weather. If you ask the mayor, he’s been resourceful, securing every dollar of external funding he can find. In 2015, for example, his city added its first-ever chief resilience officer (CRO), thanks to a multiyear grant from a nonprofit philanthropy. The mayor and his team responded enthusiastically to that grantmaker’s pioneering program to build climate resilience strategy and implementation capacity.

Then, in 2021, Mayor Joe’s city was awarded a Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to fund pre-disaster “hazard mitigation,” also known as risk reduction, which included the purchase of properties in flood-prone areas to create wetlands that can absorb flood waters.

Over his decade in office, Mayor Joe also welcomed technical assistance and advocacy groups with insights on climate justice, plus a number of firms, including private funds and reinsurance companies. These organizations pitched concepts for raising project capital, such as environmental impact bonds (a pay-for-success financing tool that ties repayment to the performance of a project, such as how much stormwater is diverted when it rains, which helps de-risk an investment); granting a 99-year private lease on the local public water utility (which would address an immediate cash flow problem by privatizing a public asset); and a parametric insurance policy (with a predefined payout amount for a predefined type of loss). But in each case, there seemed to be no room in the city budget (especially if avoided loss is not in the calculus), or the community had no appetite for the proposal.

In 2025, therefore, Mayor Joe feels as though he’s back at square one: The one-time grant funds are gone, as is the CRO. But extreme weather is still around, and worsening: Losses are growing, and as Brookings research has confirmed, the gap between disaster events is now shorter in many places too. That means communities like Mayor Joe’s are confronting a new and costly extreme weather event before they have been able to recover meaningfully from the last one.

Now, Mayor Joe is told his only options are to raise taxes on already stretched constituents—an even harder political sell today—or wait for more federal help. But that help likely won’t come unless the next disaster is so catastrophic that it qualifies for a presidential disaster declaration.

The challenges facing our fictional mayor are all too real and all too common. Yet nationwide, there are some clear signs of progress. According to public opinion research, for example, the nation has made progress in raising public awareness about the need to build community resilience to extreme weather and the growing impacts of a changing climate. (Voters and taxpayers can agree on this, across party and other divides, even when they disagree on why the weather is changing.) We’ve also seen important advances in engineering, successful climate adaptation plans in many cities that had CROs serving over the last decade (some still do), and innovative grant programs such as BRIC (which the Trump administration recently cancelled, although the program’s fate is still being litigated). In theory, then, we’ve made progress on building both the will to act and the way, or means, to move forward.

But when it comes to how communities will pay for and sustain significant financial investments in resilience, and how the value of resilience is conveyed to public and private sources of funding, progress has stalled in the U.S. That’s mainly because our dominant mental models and operating systems are reactive, dated, under-resourced and fragmented.

In this report, we explain why and outline a new way forward—focused on shared risk, shared value, and new pricing—illustrated with working examples from a range of pioneering states and communities. State and local governments are the largest real estate asset managers, as well as critical investors, in every community across the nation (while Tribal governments got an earlier start on climate adaptation but face distinct financing, legal, and institutional challenges). With the right mindset and tools, they can reap significant benefits. Without them, they face unique and ever greater risks and losses, as we outline next. (Disclosure: One of us, Posner, is head of public finance at The Resiliency Company, a 501(c)3 nonprofit, and leads its Resilient America initiative.)

The stakes and the disconnects

The form of resilience this report focuses on is protecting the built environment, whether through engineered or nature-based solutions (such as restored wetlands that protect against storm surges and other hazards). The ability to convey the value of protecting our communal and private places—along with all the connective elements that make where we live, work, and play safe and secure—is essential. Constituents, local businesses, public officials, investors, and others all need to understand that value in clear and meaningful terms.

In our conversations with decisionmakers across the country, it is often said that many local leaders are unaware of the true size and scope of the physical climate risk their communities now face, let alone how that risk may change. Yet leaders are under growing pressure to figure out how to reduce that risk.

Compounding this challenge is the reality that in many places, we have conditioned local governments to not connect their budgeting process to the concept of resilient infrastructure. It’s not surprising, then, that for many leaders we have spoken to, resilience is a “nice-to-have,” and a grant-funded extra—not a “must-have” for every community. If we can integrate affordable resilience and adaptation concepts into local government best practice, the public finance and policy levers that government has—which can be incredibly powerful—will unlock new opportunities at scale.

Local and state governments are not only more proximate to their constituents than the federal government, but also more on-the-hook to pay for new infrastructure investments (and many competing needs). Big-ticket congressional legislation tends to win the headlines, but according to recent Brookings analysis, 80% of America’s public infrastructure spending—on roads and bridges, stormwater systems, and other physical structures—is still paid for by state and local governments, not the federal government. Yet our traditional financing model for infrastructure—which relies heavily on municipal bonds, property taxes, and special revenue assessments—isn’t designed to handle the complexity, urgency, and scale of today’s climate threats, let alone tomorrow’s.

If we’re going to solve this, we need to rethink how risk is measured, how value (especially the value of avoiding loss) is defined, and who pays for the biggest financing challenge facing mayors and other leaders: the upfront cost of building or retrofitting things in ways that are safer as well as smarter. There is a return to smart investments in resilience, but our systems and practices have largely failed to capture those returns so far.

As a report in The Epicenter, a nonprofit media hub focused on resilience, outlined earlier this year, benefits such as avoided property damage, reduced insurance premiums, more stable tax bases, business continuity, and better public health are all key components. If these were valued in financial transactions, they would change the economics of operations, management, and capital improvement plans for many governments in the U.S.

The weather is getting worse and the system is not getting better

In communities across the country, the weather is not just extreme, but relentless. Floods are getting stronger and lasting longer, wildfires are bigger and less controllable, and hurricanes are intensifying more quickly.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the U.S. now experiences a disaster costing $1 billion or more every 18 days, up from every 72 days in the year 2000. These large-scale disasters are projected to become weekly events by 2030. And they’re not just affecting communities in areas that are the most historically disaster prone. One in three Americans has been affected by extreme weather in the past three years. As earlier Brookings research noted, “The average annual damages [in the U.S.] from weather- and climate-related disasters jumped from $18 billion in the 1980s to $81 billion in the 2010s, and the 2020s are easily on pace to shatter that record.”

It’s no surprise, then, that insurance markets are pulling back. Florida, California, and Louisiana are canaries in the coal mine. In many of these areas, insurance is becoming unaffordable or simply unavailable. Premium spikes are leading to experiments and innovations such as community-based catastrophe insurance and parametric policies, but these tools are still early stage and subscale. One reason is that the viability of private insurance depends on where and how we build, as well as how well we protect physical assets. Insurance, after all, kicks in after a loss event. So, financing resilient infrastructure is upstream from the insurability of property, both private and public, and the affordability of insurance coverage. According to a recent Bipartisan Policy Center analysis, another reason is that in much of the nation, there is little relationship between a community’s risk mitigation efforts and the insurance rates it faces.

Complicating all this is the fact that the places most in need of resilience investment are also the least resourced. The federal government underscored this last year, with data from the newly enacted Community Disaster Resilience Zones program at FEMA. To frame the need for targeted investments, FEMA published an analysis of the most natural-disaster-prone census tracts (tracts are typically home to a few thousand households within a larger town or city), overlaid with tracts, most of them low- to moderate-income communities, that have been historically disinvested and economically marginalized. Nationwide, over 400 of these communities sit at the front lines of weather-related disasters, but have limited financial capital to pay for critical investments in resilience. Places such as St. John the Baptist Parish, La., or McDowell County, W.Va., are in high-risk disaster areas in nearly every government assessment, but collect less than half of their operating budget from property taxes or have seen population declines of over 80% in the last century—creating nearly impossible fiscal conditions.

The equity stakes of finding smarter approaches to financing resilience are huge. Yet most local budgets and local government operating capacity, not just those of low-income communities, were never set up to absorb major, let alone recurring loss of physical infrastructure or community-serving buildings, vehicles, and other public assets. And climate-driven needs are compounding existing infrastructure backlogs and the need for much better goal setting, project planning, and other “predevelopment” work.

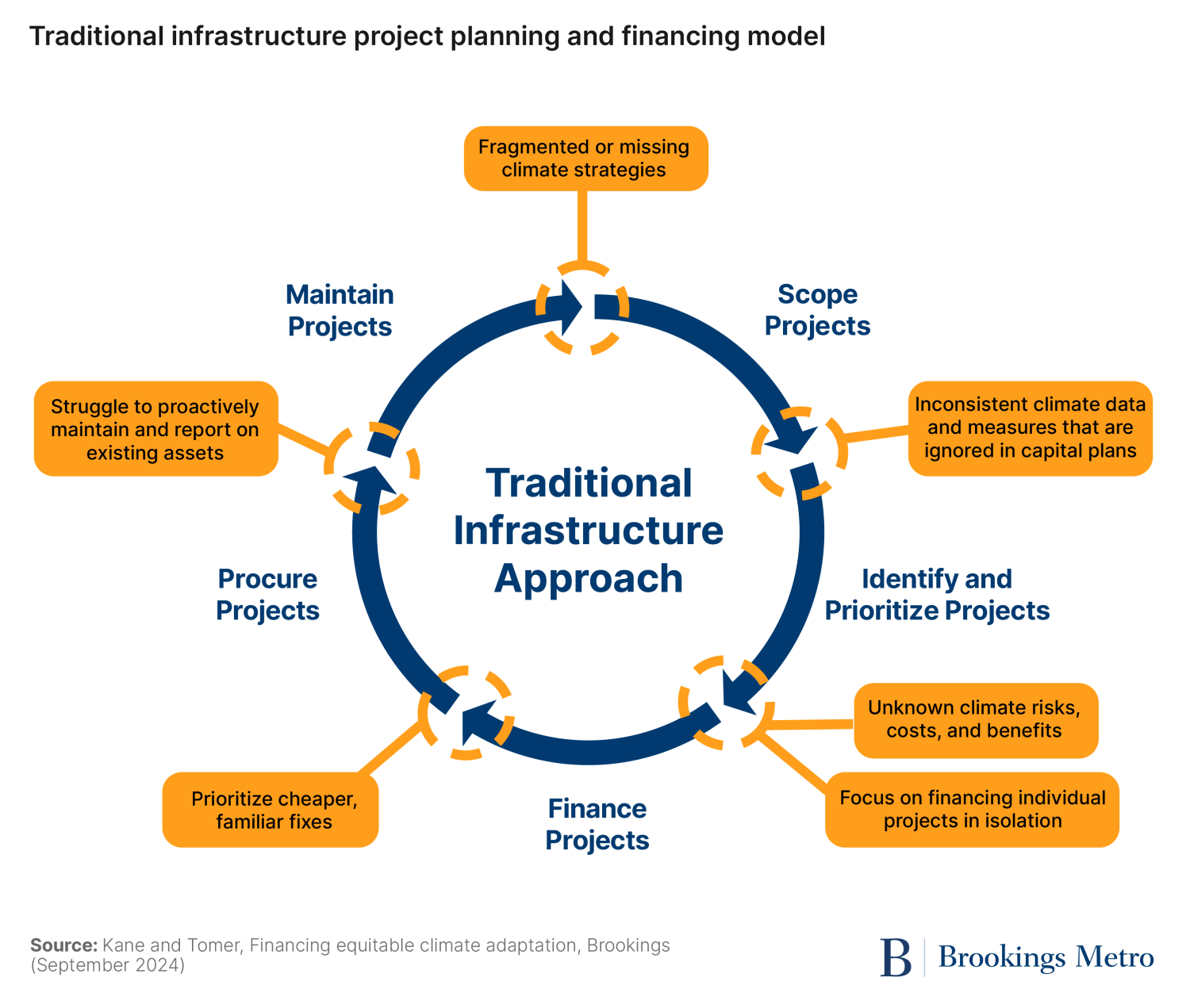

Zooming out from infrastructure capital needs specifically, the financial tools most available and familiar to local governments—primarily general obligation bonds and assessments—depend on voter support, which is constrained by inflation, higher housing costs, federal and other funding cuts, and competing public needs. No wonder our conventional infrastructure planning and finance model is so reactive and limited when it comes to accounting for climate risk, as detailed in previous Brookings research (see Figure 1).

Furthermore, as previewed above, the federal government’s role, while still meaningful, is limited by design, and this underscores why state and local leaders need to look for new solutions now.

Creating the BRIC grant program, for example, was a positive, bipartisan step by Congress in 2018. But the program was modest in scale relative to the need, with a maximum annual appropriation of $1 billion, and it was quickly and significantly oversubscribed, according to federal data. The complexity of the application requirements, together with a state-brokered submission process, also gave wealthier, more prepared localities, usually large urban areas, an advantage; these “superusers” were far more successful at winning BRIC grants.

The federal government has shown leadership in other ways, to be sure. Under the Biden administration, for example, the White House Office of Management and Budget issued first-of-its-kind guidance to federal agencies on making “climate-smart infrastructure investments” via the massive new inflow of capital from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and other sources. But that guidance was largely advisory, and it did not offer solutions for additional project costs, or what practitioners have informally thought of as a “resilience tax.”

Meanwhile, key investment tax credits have often been important, especially for making local energy projects more affordable and resilient; for example, in the form of solar-plus-storage infrastructure. But tax credits are complex to use, and in July, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act phased out a huge volume of them. As analysis by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and Brookings researchers has documented, many local and Tribal government leaders don’t have the staff, training, or partnerships to successfully “stack” grants, tax credits, and loans, even when their communities are eligible and Congress has resourced the relevant federal programs.

It’s no wonder, then, that resilience investments are still widely viewed as optional capital improvements—until they become urgent emergency rebuilds. How can community leaders fund something with a high upfront cost when they seemingly cannot afford to, but also cannot afford not to?

In many ways, we’ve set local officials up to fail. As we’ve outlined, they’re essentially given two options: raise local revenue or wait for state or federal subsidy. But neither path works fast enough, and both are riddled with pitfalls. Raising taxes is often regressive, politically risky, and dependent on approval by local voters and sometimes also their state government (many states restrict local revenue policies). Waiting for help may mean suffering major new losses—at least some of them preventable—through another disaster event.

Only rarely do the tools local leaders are given directly and systematically factor in: 1) the value of the losses that would be avoided by investing in resilience; or 2) direct participation by those, other than the taxpayer at-large, who “co-benefit.” That’s because resilience investment does not fit the traditional infrastructure mold:

- It doesn’t always generate a direct revenue stream.

- Its benefits—fewer floods, lower insurance costs, more stable energy systems—are distributed across sectors and over time.

- It sometimes crosses jurisdictional lines and agency silos, making coordination, accountability, financial participation, and the payoff calculation more difficult.

The U.S. needs a new, actionable, and scalable investment framework that acknowledges the full ecosystem of risk and reward. This new approach must be built on several key principles:

- Shared risk: Local, state, Tribal, and federal governments shouldn’t carry the burden alone. Risk is systemic, often affecting a range of private parties or collectives (e.g., members of a local business improvement district) with financial and other stakes in the investment.

- Shared value: Given shared risk, other beneficiaries such as utilities, insurers, and major employers should be part of the equation (as should their regulators).

- New pricing: Given shared value, we need to (and can) embed avoided losses and resilience dividends into financial decisionmaking. It’s not just smart in principle—it’s increasingly possible with better data and modeling.

These principles need not apply only to projects and discrete interventions. They can be powerful when applied to citywide or communitywide strategies that define multiple interventions and consider how resilience improvements reinforce each other and yield even greater dividends; for example, by combining levees, rain gardens on public lands or streets, and floodproofing of properties. What’s more, as a leading engineering expert on resilience told us, finance innovation and engineering innovation can directly support each other by reducing hard costs and making investments more attractive and the financing more executable.

Rethinking what’s possible: Four models of innovation

Though the public has been losing confidence in government, especially the federal government, more or less steadily for decades, one of the nation’s strengths is that our federalist system allows for local and state tinkering and innovating in our so-called “laboratories of democracy.” What’s more, local government remains far more trusted overall. It’s crucial, then, that across the country, innovative models of infrastructure investment are showing what’s possible when leaders think outside the “bond-and-tax” paradigm. Four models stand out, and they are not mutually exclusive:

The revolving fund flywheel (Illinois Finance Authority)

Illinois is leading the country with a first-in-the-nation model to fund climate resilience through a state-run loan fund that goes beyond traditional capital infrastructure and supports the full lifecycle of resilience investments. Authorized through bipartisan legislation and administered by the Illinois Finance Authority, the program adapts a familiar tool—the state revolving fund—for a new purpose: climate adaptation.

What makes Illinois’ approach innovative is not just what it funds, but how it shifts the structure of resilience finance. For years, most resilience projects in the state were funded through small-scale, one-time grants. These grants were important for seeding local planning and early implementation, but they were limited in scope and impact. Funding something critical exclusively or mostly through grants is a simple and familiar approach, but it is often difficult to scale or speed up. Worse, it turns public “investment” into a lottery for the fortunate few. As project demand grew and costs increased, the state recognized the need for a more scalable and durable solution.

Illinois developed a financing model that allows public resources to be recycled and leveraged. Modeled on the State Revolving Fund (SRF) concept long used for clean water and drinking water projects, the fund makes low-interest loans that are repaid over time by one borrower, typically a municipality or public entity, and then re-lent to the next borrower using the same pool of capital. The repaid principal plus interest maintains the fund itself, but because it is a public service with no profit aim, the interest remains below market rate.

This self-renewing model allows the initial investment to support multiple rounds of projects. For example, the Clean Water SRF, seeded by the Environmental Protection Agency thanks to federal legislation enacted in 1987, has delivered over $172 billion in capital nationwide as of fiscal year 2023, far exceeding its original capitalization by recycling repayments into new loans year after year, with interest.

Based on conservative estimates, $1 in public capital can support $3 in total project costs, especially when paired with bond proceeds and other leveraged funds. Critically, the Illinois fund does not just cover construction; it can also support operations, maintenance, staffing, insurance, and other long-term costs associated with building community resilience. This approach acknowledges that resilience is not a one-time investment but an ongoing public responsibility.

The Illinois Finance Authority designed its fund with the expectation of layering in federal resources, including the BRIC program and the Inflation Reduction Act’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. Although those federal dollars have been delayed or reduced, Illinois moved ahead with a structure that is self-renewing and ready to amplify additional public, private, and philanthropic capital as it becomes available.

How do we move from one-off grants to continuous, scalable investment in resilience? Illinois demonstrates an important part of the answer: State institutions can do more than issue debt. They can build financial infrastructure that multiplies public value over time and responds flexibly to future risks.

Key takeaway: Illinois has transformed a well-established and tested public finance tool into a modern platform for resilience. By supporting both capital projects and long-term operations, the state has created a structure that is fiscally responsible and politically viable—and that begins to meet the scale of the climate challenge.

The capacity aggregator (Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank)

Rhode Island’s Municipal Resilience Fund is the capital deployment arm of the state’s broader Municipal Resilience Program. The program begins with a structured, collaborative risk assessment and planning process in which municipalities receive support to identify and prioritize locally relevant resilience projects. This is an essential first step for smaller or under-resourced jurisdictions, as they may not have in-house climate planning capacity. Thus, the program is designed for more equitable delivery, not just scaled delivery, of vital capital.

The evolution of Rhode Island’s approach is telling. Initially, the state supported resilience projects through grant funding. That worked to promote resilience planning on a small scale, but as demand grew and project size increased, it became clear that a more durable, sustainable financing approach was needed. In response, the Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank shifted toward a leveraged loan model, using its experience managing state revolving funds to offer long-term, low-cost capital. On a conservative basis, every $1 in public resources can now support $3 in project costs. This turns a finite pool of funds into a self-renewing and significantly more powerful platform to meet mounting demand.

Once projects are ready for implementation, the Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank can provide funding through a mix of revolving loan capital, state bond proceeds, green bonds, and federal infrastructure funding. The result is a layered financing model that does not rely on a single funding source or force local governments to go it alone. Among other strengths, this model enables small cities and towns to punch above their fiscal weight, accessing both capital and expertise without needing to master the complex mechanics of resilience finance.

Key takeaway: States can enable scaling and offer communities both technical expertise and low-cost capital by acting as aggregators. Rhode Island’s shift from grantmaking to revolving finance illustrates how state-led innovation can transform limited, one-time support into a longer-term, more expansive investment strategy.

The community trust builder (city of Ann Arbor, Michigan)

While many communities struggle to communicate the long-term value of resilience investments, Ann Arbor, Mich., has become a national example of how to credibly frame climate resilience as a necessary, shared, and investable public good.

In 2022, city voters approved a new “climate millage”—a dedicated property tax levy—to fund resilience and clean energy projects over a 20-year horizon. The program, formally known as the Sustaining Ann Arbor Together (A2ZERO) Climate Action Millage, offers a blueprint for other municipalities seeking local financing mechanisms that are both politically viable and mission aligned.

Notably, the tax measure funds a mix of climate mitigation and adaptation strategies, including:

- Building electrification and energy efficiency for low-income households

- Urban tree planting and green stormwater infrastructure

- Resilient energy systems such as microgrids and solar-plus-storage

- Public transit, mode shift, and electric vehicle infrastructure

Climate Resilience Districts, such as those enacted by the state of California, and similar revenue innovations offer local leaders the same sort of flexibility. But committed local leadership is critical. What sets Ann Arbor apart is not just the funding mechanism, but the political strategy and communications approach that got it passed. City leaders spent years cultivating public trust, embedding climate goals in other city services, and translating the costs of inaction into relatable, local terms: higher insurance costs, utility disruptions, public health risks, and infrastructure degradation. The city also framed the investment as generating a return, or resilience dividend, not just a cost—highlighting how each project would reduce the long-term taxpayer burden, increase neighborhood livability, and strengthen social cohesion in the face of worsening climate threats.

Key takeaway: Climate resilience becomes more fundable at the local level when it’s framed as a long-term, essential benefit—not a discretionary cost—and tied to public trust, transparency, and visible local impact.

Risk sharing (city of Tulsa, Oklahoma)

Tulsa, Okla., shows how a city can act on shared risk by building durable, locally led systems for resilience investment.

After experiencing devastating floods in the 1970s and 1980s, the city developed one of the most comprehensive flood mitigation programs in the country by recognizing that repeated loss was not just a federal responsibility, but also a local fiscal, economic, and social challenge. Tulsa institutionalized this understanding by creating a dedicated stormwater utility fee in 1986, which provided a consistent revenue stream for proactive infrastructure investments. The city also passed multiple rounds of voter-approved general obligation bonds, which helped fund green infrastructure, floodplain restoration, and voluntary buyouts of high-risk properties. Federal support from FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program and the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery program supplemented these efforts, but the core financing came from locally controlled sources.

This approach reflected a simple principle: When risk is shared across households, insurers, and public agencies, the responsibility to reduce that risk must be shared as well. While Tulsa did not formally co-finance projects with private utilities or insurers, the stormwater fee applied to all property owners, including businesses, civic institutions, and households. In this way, the private sector contributed financially based on their share of impervious surface area, which correlates with runoff and flood risk. The insurance industry’s role was indirect but meaningful: As the city reduced its flood exposure through these investments, it improved its Community Rating System (CRS) score under FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program. Tulsa now holds a Class 1 CRS rating (one of only two cities in the nation to do so), which provides up to a 45% discount on flood insurance premiums for residents and businesses. Crucially, Tulsa did not wait for perfect data or elaborate modeling. Instead, it applied common-sense rules: If the same neighborhoods flood repeatedly, the cost of inaction is compounding, so the city should act there.

The business community, public works agencies, and residents supported these measures politically and practically, recognizing that flood mitigation efforts help protect property values, reduce economic disruption, and maintain insurability. This is not a case of formal co-investment, but rather one of aligned incentives and shared value (demonstrably better outcomes). Tulsa shows that local governments can lead on resilience by embedding risk reduction into everyday governance and generating value in return.

Key takeaway: Local governments can lead effectively on paying for resilience by treating risk as a shared problem and investment as a shared responsibility. This is a replicable model grounded in fiscal prudence and cross-sector value, where shared value and shared risk are two sides of the same coin.

From paradigm to action

To give more local governments access to capital that’s fit for purpose, the field needs an accessible and actionable framework for investing in climate-resilient infrastructure. The table below shows the fundamentals, based on the nation’s most innovative and promising models:

|

Foundational shift |

What’s needed |

|---|---|

|

Understand risk as a shared, ongoing, and systemic challenge, not a burden to be handled piecemeal and incrementally by each stakeholder acting alone. |

Use weather, economic, and engineering data to quantify risk to properties, public assets, and balance sheets. Share this data with public and private stakeholders. Aim for universal comparisons between places. |

|

Incorporate resilience into financial transactions, instead of “siloing” resilience investments into infrastructure project costs. |

Make resilience a core component of infrastructure deals. Reductions in insurance claims, continuity of business, and property value appreciation are some of the potential outcomes that have value. |

|

Share the burden in the same way as the value, instead of relying on narrow, conventional sources of funding to go it alone. |

Engage the broader spectrum of beneficiaries, such as insurers, utilities, manufacturers, health care providers, and small and large businesses in the area. There are many ways they can support place-based resilience. |

Making community resilience both must-have and possible

Waiting for the next disaster or grant cycle is not a tenable resilience strategy, nor is raising taxes across the board to support more local government spending and debt. The good news is that we have models that work to invest in vital infrastructure in ways that make communities more resilient to the growing impacts of our changing climate. In addition to the tragic loss of life and health, those impacts include mounting, recurring, and unpredictable financial losses that are challenging community residents, public officials, businesses, nonprofits, and insurers alike.

These innovative models call for a new mindset and more flexible approach. The main challenge now is scaling the models, funding them, and equipping local leaders—and their partners in state and federal government, local property ownership, capital markets, and elsewhere—with the right mix of tools, data, and collaborative problem solving. And the proven examples featured in this report only scratch the surface of what’s possible as, for instance, discussions of innovative revenue sources and value capture expand across the country.

To be sure, resilience capital on a much greater scale is not the only need, and some looming challenges—such as sea level rise, mega-droughts, and mega-fires—pose threats on a greater geographic scale, calling for coordination between states and with federal and Tribal governments in the decades ahead. But as this report’s locally focused examples underscore, innovative financing solutions often go hand in glove with other critical pieces of the puzzle, such as models for organizing local business owners into improvement districts or other shared-interest pools (such as homeowners’ associations), considering new ways to define property rights and land stewardship, offering technical support at scale (especially to smaller, low-resource communities in a state), and making reliable climate intelligence more accessible and actionable by all.

No single actor can solve the resilience financing gap or drive the shifts we have outlined and illustrated. Conversely, that also means that a range of actors can help right away, including:

- State, local, and Tribal officials can replicate the models—grounded in the mindset and principles—we have outlined. The federal government can certainly help too (see below), but other levels of government cannot afford to wait for federal reform and funding, especially traditional project grant funding.

- Government finance officers can integrate resilience into capital planning by recognizing it as part of existing operations and maintenance, and helping to quantify and communicate value (the “resilience dividend”).

- Philanthropy can accelerate progress by supporting planning and policy advocacy, connecting grantees to public sector partners eager to problem-solve, and blending grants and impact investment tools (program-related investments and mission-related investments) into public finance tools that can scale.

- Other impact investors, such as motivated pension funds and community development financial institutions, can help price and structure deals that account for avoided losses, long-term savings, and shared value, as we have outlined.

- Regulators can invite discussions, especially with utilities and insurers, that recognize avoided losses and other resilience dividends, instead of reflexively blocking forward-looking investments because they don’t fit a traditional mold. Lawmakers, governors, and city and county executives can encourage (and in some instances, enable) the regulators and the regulated to do so.

- Federal agencies can support performance-based block grants or other proactive sources of flexible funding that empower local governments to set clear resilience priorities, blend funding from multiple programs in smart and practical ways, and deliver results, rather than one-size-fits-all, siloed, compliance-driven models.

- Real estate developers and home builders can proactively adopt resilient design standards, partner with government and civic organizations on hazard mitigation, and protect long-term safety, function, and property value by investing in durability upfront.

- Health care systems and hospitals can strengthen community resilience by investing in it as a critical social determinant of health. The Healthy Communities movement and a large body of research has helped to point the way for decades, reflecting the growing recognition—in the medical profession, health care management, and public health, not to mention the public at large—that factors such as safer housing, reduced loss and trauma, resilient livelihoods, and reliable infrastructure are foundational to preventing illness and death, reducing costly stress, and protecting the vulnerable.

Climate-related losses are growing, and our risks are shared. These risks are widely—if unevenly—distributed. But so are the benefits and dividends of making critical investments in more resilient infrastructure and communities, on a much larger scale, as soon as we can. It’s time to give Mayor Joe and every committed local leader like him a better toolbox and a viable path forward. The next disaster won’t wait.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

This report is made possible by support from The Kresge Foundation. The views expressed in this report are those of its authors and do not represent the views of the The Kresge Foundation, their officers, or employees. For helpful comments on an earlier draft, the authors are also grateful to Michael Berkowitz, Dan Carol, William Fazioli, Beth Gibbons, Shayne Kavanagh, Zachary Lamb, Carlos Martín, Robert “RJ” McGrail, Victoria Salinas, Laurie Schoeman, John Shapiro, and Prithi Trivedi.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).