Yesterday one of us said he thought the macro conditions for the “reshoring” of significant advanced industrial production were right but that the opening of new plants wouldn’t be easy.

A lot has happened since the United States was a colossus of industry. Regional economic ecosystems matter, yet much has been lost over 30 years in the way of local know-how, worker skills and supply chain capacity. One result is that a number of high-profile reshorings have either been difficult (GE’s return to Appliance Park in Louisville) or unsuccessful (Google and Flextronics’ effort to assemble the MotoX smartphone in Fort Worth). In these cases the erosion of the local knowledge, skills and supplier base has greatly complicated the scale-up of returning firms.

Yet that is a qualitative assessment. Can we make the point in sharper terms? In fact we can, using data from a forthcoming analysis of the geography of America’s R&D- and STEM worker-intensive “advanced industries,” which range from aerospace and automotive manufacturing to software and other high-tech services. Check out these maps:

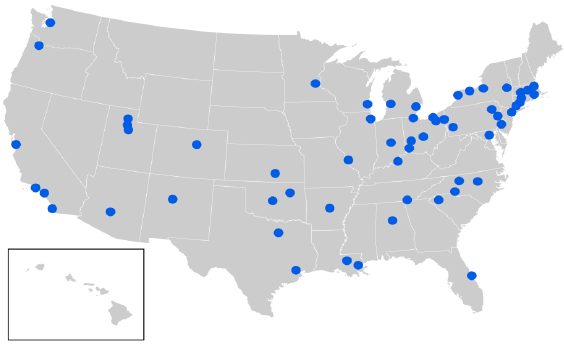

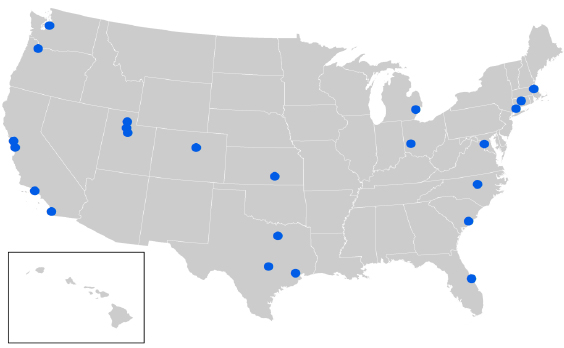

Large U.S. Metropolitan Areas with Over 10 Percent of Total Employment in Advanced Industries

1980

2013

Source: Brookings Analysis of Moody’s Data

These maps, while not a perfect depiction of the condition of regional advanced industry ecosystems, provide an indication, and it’s not encouraging.

In 1980, 59 of the country’s 100 largest metropolitan areas had at least 10 percent of their workforce in innovative, technical advanced industries. By 2013, only 23 major metros contained such sizable concentrations of advanced industry activity. Granted, technological change and productivity increases explain some of this reduced intensity, but that’s not the full story. Other countries that have been the recipients of U.S. offshoring have grown employment in these sectors substantially. All of which suggest that the American advanced industry platform has thinned out substantially and inordinately, so that less than half as many large metro areas have the density of advanced industry activity that they had in 1980. That means that on balance many fewer U.S. metropolitan areas now have the dense supplier bases and deep pools of technically relevant workers necessary to support new advanced industry growth.

That’s a problem. In an era when clustered capabilities matter as much as labor or energy costs, the United States has a lot of work to do to rebuild its network of regional industrial ecosystems. Whether it can manage that will determine a lot about how the reshoring opportunities plays out, metro area by metro area.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Reshoring: Why It’s Not Easy

October 3, 2014