A version of this post appeared on the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) blog.

Despite some early success, the mobile money industry’s future remains unclear as many markets remain slow to ignite. For either a Mobile Network Operator (MNO) or a bank, starting mobile money operations is expensive, complex, and relatively high-risk. As a result, mobile financial systems in developing countries tend to be dominated by a few large players, mostly mobile operators. This dynamic often reduces incentives for the dominant firm to lower prices or innovate. In the end, these market dynamics hinder financial inclusion as customers tend to use mobile money systems infrequently, for a limited range of applications, and continue to rely on cash.

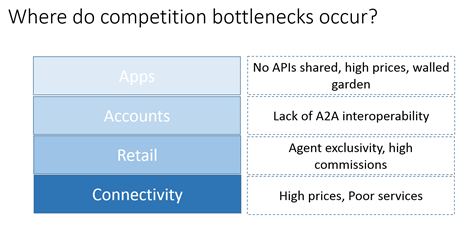

In a recent paper, David Evans and Alexis Pirchio, two economists from the University of Chicago and Global Economics Group, identified four layers in mobile payments platforms where competition bottlenecks can occur:

- Connectivity: in Zimbabwe, EcoCash was investigated because they created a separate protocol for banks to offer their transfer services at a much higher price than what the wireless carrier Econet was charging those connected to EcoCash.

- Agent network: in Kenya Airtel filed a complaint with the Competition Authority of Kenya (CAK) to force Safaricom to remove the exclusive arrangements with its agents. The CAK ordered Safaricom to open up its network to other players and prohibited the wireless carrier from charging extra for outside access.

- Accounts: In Kenya, an M-Pesa customer can send money to a non-Safaricom phone, but the recipient cannot store the money in their mobile wallet. Instead, they must withdraw the money as cash from a Safaricom agent.

- Applications: the mobile money provider creates a bottleneck for value-added services by deciding whether or not to allow the service to access its communications, accounts, and agent network platforms. This is the case in Kenya with M-Pesa.

Moreover, the data created by the use of digital financial services by the poor can also be used by firms to propose better services and deals, improved credit access, etc. This question of data ownership cuts across these four layers and constitutes a fifth level of competition analysis.

So what can countries do to navigate complex competition issues?

In this recent paper, I try to address this question.

The lack of competition is hard to address as regulators wrestle with complex market incentives. On the one hand, a monopoly incentivizes the dominant player to invest, and this is something the regulator will want to preserve. On the other hand, a monopoly prevents market players from entering the market, reducing prices, or innovating for customers, and this is something the regulator will want to address.

Some of the questions in-country regulators are wrestling with are: (i) When is the right time to intervene? (ii) Which intervention will foster competition and accompany the market, without stalling its growth? (iii) Which regulatory agency will have jurisdictions over the claim or dispute?

Government regulators and investors could work together to foster in-country competition by setting in motion various types of activities. For instance, they could help strengthen the mobile money capacity or expertise of competition authorities. Competition authorities often lack the right expertise to address competition bottlenecks in mobile money markets. This expertise would empower them to prioritize mobile money investigations as they arise, push back possible political interference and, bring credibility to their investigations and decisions.

Regulators and investors could also promote coordination by providing a forum to discuss a coordinated strategy. They could boost in-country and global mobile money competition ecosystems. Regulators will face similar issues in many markets so efforts should be made to both extract and share lessons globally and to link policy makers together to share experiences and knowledge. New mechanisms or institutions may be needed to allow competition authorities and others to share knowledge and experiences across markets.

Finally, aside from regulatory interventions, innovations could disrupt the market power of leading incumbents and alter in-market competition dynamics. In India, payment and banking startups such as Novopay use small neighborhood retail stores as business correspondents to open bank accounts and provide deposit and withdrawal services. This allows several financial services providers to use the same agent network. Another example is the LevelOne Project initiated by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which aims to guide all digital financial services players (both mobile and banks) towards a common digital payment infrastructure inclusive of the poor.

How do you think competition issues are affecting the mobile money landscape? What interventions would foster competition without stalling market growth? What is the role of the donor community in this space?

These questions will generate much debate over the years to come. We are only scratching the surface in this post and invite you to contribute your thoughts below.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Removing barriers to competition in mobile payments platforms

November 2, 2015