This publication is accompanied by a specific federal proposal to launch a regional transportation block grant program. That proposal can be accessed here.

Executive summary

For the better part of a decade, America’s two largest political parties have put forward platforms to rebuild and renew America. One of the investment areas with the broadest agreement is infrastructure. The economic case for maintaining and modernizing physical assets, such as fixing the country’s bridges or extending its broadband networks, continues to be clear. Yet the emerging political consensus also reflects an underlying philosophical alignment: Reinvesting in our cities and towns can uplift households, businesses, and entire communities.

Yet delivering transformative infrastructure with regional or national impacts is complex. Unlike the kinds of routine projects managed within a single jurisdiction, transformative projects address structural needs across an entire region, often carrying a price tag beyond a single jurisdiction’s purchasing power. These projects demand coordination among multiple jurisdictions—pooling diverse funding sources and employing an array of skilled tradespeople to deliver multiple smaller projects at once. Every region’s definition of “transformative needs” is a bit different too, such as rebuilding freight junctions across Chicagoland or protecting metropolitan Houston from future flooding.

Federal Washington has a long tradition of requiring regions to plan out their infrastructure assets and systems. Federal transportation, water, housing, and economic development policies each compel regions to make long-term plans, in many cases even providing funds to facilitate the process. What Congress has mostly failed to do, though, is provide enough steady capital to accelerate and underwrite those plans’ specific projects. Instead, the current federal approach—most recently through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA)—primarily sends infrastructure funds to states using formulas or through competitive processes that unduly burden regions. Even worse, states often fail to meaningfully collaborate with local and regional leaders when deciding how they’ll use their federal dollars.

The result is a string of missed opportunities. Too many transformative efforts never shift from planning documents to shovels in the ground. Projects that do advance move more slowly due to funding shortfalls, complex compliance rules, or limited labor supply. Even when recent federal laws tested new approaches, competitive grantmaking has proven to be an unpredictable source of funding for localities and an inefficient way to strengthen relationships among regional partners.

America needs a new federal approach to fund transformative infrastructure projects. The federal government needs more efficient ways to translate their dollars into region-serving projects, allowing federal agency staff to focus primarily on knowledge sharing, testing new ideas, or delivering true mega-projects. Meanwhile, receiving more direct funding would give regions greater autonomy to construct projects that no single municipality can deliver alone—and more dependable funding would help regions build the internal knowledge and capacity that their state peers have. Regions would be able to tap a new source of revenue and leverage it to create more value from existing investment channels. With this approach, regions would be free of a “one-size-fits-all” approach from the state down, able to respond and execute with flexibility.

Regional block grant programs are ideally suited to help rebuild America from its economic engines outward. New programs would send federal funds to every region in the country, allowing regional governments and their municipal peers to accelerate projects of regional significance that they’ve prioritized within their federally supported long-term planning efforts. Flexible planning funds would help nurture regional relationships among local officials, civic leaders, and industry partners. Federal staff in Washington, D.C. and field offices could focus more on addressing complex questions received through technical assistance requests from regional partners and look for common lessons to share across the country.

Federal officials have had great success running block grant programs, but they have not used those program designs to their fullest extent within the infrastructure sector. This report makes the case that regional infrastructure matters, and consolidates lessons from the most recent federal investment period. Federal lawmakers, regional leaders, and other stakeholders should apply these lessons as they consider how to launch new regional block grant programs in future legislation.

What do we mean by ‘region’ and ‘infrastructure’?

This report aims to explain why the federal government is not investing enough in regional infrastructure, but both “region” and “infrastructure” are prone to different interpretations. For the purposes of this report:

- We use “region” to refer to a populated area that includes more than one municipality and is anchored around one or more central economic nodes. It could align with a federally defined geographic designation such as a metropolitan or micropolitan area, but does not necessarily have to. We never use “region” as a reference to a federal multistate designation, such as regional commissions. We also do not use “region” to reference geological features, such as a watershed.

- We define “infrastructure” to include human-made transportation, water, energy, and broadband networks. We also use the term “built environment” when we reference infrastructure and other human-made structures such as commercial real estate and housing. We then use “capital projects” to reference efforts to physically build any such structures.

Of course, governance across infrastructure sectors and between states is varied and complex. Water infrastructure is built and operated at a regional scale by utilities, while transportation uses a patchwork of state, regional, and municipal governance. We do our best to call out these distinctions wherever possible.

The federal investment moment

Beginning in 2021, Congress initiated the most significant federal investment campaign in the built environment in at least half a century. Taken together, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) committed more than $1 trillion in federal grants, loan guarantees, and tax credits to modernize infrastructure systems.1 While the infrastructure portions will keep up with the historic average (Figure 1), the totals are even larger when counting industrial policies such as modernizing manufacturing facilities, supporting emerging technology hubs, and diversifying fuel sources.

As enormous as the funding total is, the federal government owns very few physical infrastructure assets around the country, and even fewer industrial assets. However, it’s in the federal government’s best interest to ensure infrastructure enables economic growth and physical security in every community. Converting federal fiscal commitments into projects, then, requires close coordination with state, regional, and local governments and private businesses that are responsible for long-term planning, predevelopment activities, and the majority of project costs. The result: Federal funding is only as impactful as the ability of states, local governments, the private sector, and nonprofits and civic organizations to work together to deliver projects that improve long-term outcomes.

Traditionally, federal law mostly uses state governments as the preferred intermediary, deferring to their policymakers on what projects will receive suballocated investment. This is especially the case in the transportation and water sectors, where the majority of federal funds are disbursed via formulas to states. Despite their enormous responsibilities as managers of these taxpayer funds, states often do not invest those funds transparently.2 Simply put, a local official or civic leader’s ability to understand how their state transportation and water officials invest federal funds is difficult to impossible. Beyond the manifold explanations and incentives for this behavior at the state level, this lack of transparency is, very simply, permitted by federal law.3

What’s more, the condition of American infrastructure demonstrates the status quo funding model is not achieving the goals Congress has set out.

Consider transportation: In 2024, 39% of major roadways failed to reach even “fair” condition, and data from 2021 shows that Americans are spending more of their commutes on roads in “poor” condition.4 Roadway fatalities are stubbornly high, having increased by nearly 10,000 per year in the decade leading up to 2022.5 Potholes and road debris increase fuel consumption and impose additional costs on motorists. These faults continued while nominal highway spending has kept climbing since 2000.6 On the most basic measures of its performance, America’s transportation system is not reaching its full potential, and there are similar performance gaps around drinking water utility maintenance, the digital divide, and affordable and reliable energy.

Now is the time to change course. With ARPA funds obligated and Congress preparing to reauthorize multiple infrastructure bills bundled under the IIJA, federal leaders should consider how best to adjust their commitments to investing in American communities. This report focuses on the extent to which federal policy directly benefits regions—and how federal policy can incentivize even more coordinated regional planning and investment going forward. Following this introduction, we explain why American infrastructure is primarily organized and delivered at the regional scale. Then, we demonstrate how current federal policy fails to uplift regional thinking, even though regional governments and municipalities complement one another. Finally, we take lessons from the most recent investment laws to justify the expansion of regional block granting.

Why regional infrastructure matters

While the federal government uses multiple, divergent definitions of regional geographies (including urban areas and urban clusters, and their offshoot metropolitan and micropolitan areas), the core principle is the same: A region is a locally contiguous place with a relatively concentrated population, anchored around one or more central cities, but which does not typically follow administrative boundaries.7 In other words, regions encompass several cities, towns, and counties of varying sizes and in some cases—such as Kansas City, Mo., Minneapolis-Saint Paul, and Charlotte, N.C.—span multiple states.

The vast majority of U.S. households live in recognizably defined regions, from the more than 20 million people living in metropolitan New York’s 22 counties to the 58,000 people living around Eagle Pass, Texas. Concentrating so many people in the same places leads to disproportionate economic productivity through network effects, with regions producing even larger shares of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) than indicated by their populations alone. Approximately 70% of Americans live in large metro areas, and those regions generate fully 76% of GDP. That is especially the case for metro areas with at least 500,000 people, as they are home to a majority of the residents and produce a majority of the GDP in almost every single U.S. state.

Infrastructure enables people and businesses within these relatively large places to access commerce, education, and other community assets. Transportation networks are designed to shuttle people and goods across the entirety of a region. Many drivers in major urban areas travel 50 miles or more every day, often crisscrossing multiple municipalities on many of those trips, including the most dense areas that generate the fewest vehicle miles traveled (VMT). Commercial airports serve entire regions, irrespective of their municipal locations. Water utilities’ operational footprints often extend beyond single jurisdictions. Broadband providers and energy utilities serve entire regions. Simply put, most American infrastructure assets consolidate at the regional scale and do not exclusively follow municipal, county, or even state boundaries, much less census tracts.

It is little surprise, then, that addressing many of the country’s most pressing infrastructure needs demands aligned actions within regions. Promoting interstate commerce and industrial development; connecting people to employment opportunities and essential services; securing environmental resilience and protecting public health; safeguarding the nation’s people through emergency response and preparedness—achieving each of these national goals depends on well-designed and well-funded regional infrastructure systems.8 It also demands actors who can work across sectoral and jurisdictional boundaries to manage such complexity.

Regional governmental bodies play an important role in managing these infrastructure needs. Since 1962, federal transportation law has required every region of at least 50,000 people to include a metropolitan planning organization (MPO), many of which are bundled within broader councils of government (COG).9 Both types of governance entities always include planning and data functions in their central missions, but many MPOs and COGs carry out much more than general planning—from owning and operating transit systems and water utilities to managing assets such as convention centers and zoos. But their most important planning role is often serving as a forum for these disparate owners and operators. MPOs and COGs use their regional board representation to serve as centralized meeting points on larger regional questions, such as allocating spending across member jurisdictions. That formation also means MPOs and COGs are structurally accountable to member jurisdictions and their elected officials.

Civic groups complement regional governments by helping to set regional infrastructure agendas, championing major strategies and new initiatives, and making bets on their regions that might need a more entrepreneurial approach. Regional business groups serve as de facto economic development leads, with some regions having multiple such groups with distinct memberships and specialties. Along with labor and other community groups, broad civic engagement “enhances the ability to gain bipartisan support and public/private funding for the regional initiative” and is associated with winning federal transportation grants.10 Philanthropies and research organizations offer innovation, independent thought leadership, and convening power, with the former also bringing investment capital to their priorities.11 Universities employ independent experts who can help design and test innovative ideas, sometimes within university-housed, regional-centric institutes. Even hyperlocal organizations such as business improvement districts help deliver on regional goals.

Decades of research by academics, policy organizations, and the federal government have affirmed why regional governments and civic groups benefit the individual municipalities they serve.12 Governments, business, philanthropic, and civic groups often collaborate out of a “desire to achieve a shared goal or preference that could not be realized by solitary action.” They also engage in regional efforts as a forum for information sharing and pooling resources,13 engaging a wider array of stakeholders, and securing funding that individual organizations may not have the fiscal or administrative capacity to secure on their own.14 And regional initiatives with broad support from civic organizations are more likely to attract bipartisan support as well as public and private funding.

Simply put, there is clear evidence that population centers benefit from taking a regional approach to infrastructure planning. That every region also looks and acts a bit different from one another is a source of American strength. Regions serve as additional “laboratories of democracy,” where each place’s unique set of stakeholders, financial resources, and economic fundamentals creates new opportunities to test solutions to common infrastructure problems, while also competing among each other to attract residents and investment to their region.

Federal infrastructure and economic development programs downplay regional significance

Members of Congress deserve enormous credit for coalescing around the need to invest more in the country’s built environment. However, recent laws still failed to address legacy practices that downplay the importance of regional governance in building prosperous places.

To start, the congressional status quo continues to focus on delivering capital grants through states, leaving regions and municipalities beholden to the preferences of their in-state leaders. This is especially the case within the largest federal infrastructure programs. States continue to receive over 87% of the IIJA’s total surface transportation spending via formula programs—equal to $79 billion per year. The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) entire $11.6 billion annual capital program (in FY 2024) first flows as funding to State Revolving Funds (SRFs), which then make low-cost loans to water utilities.15 The new $42.5 billion Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program flows entirely to state broadband offices. Formula funds are relatively cost-efficient to administer, but there is no reason that regions, with the necessary compacts and agreements for those that cross state boundaries, cannot also be direct recipients alongside their state peers.

Where federal programs do enable local governments to directly access federal funds, most downplay delivering funding at a regional scale. The Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program funded and managed by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) offers great flexibility to fund local capital projects, but is only made available to large cities or urban counties, and has been losing inflation-adjusted funding for decades. The IIJA greatly expanded the number of competitive grant programs that regions and localities could apply for, but the instinct for the project owner to serve as lead applicant effectively incentivized cities, counties, and other municipalities to apply separately.16 As a result, CDBG funding does not effectively catalyze regional projects. Even the two programs in which regional governments operate on relatively level footing—the Economic Development Administration’s (EDA) Public Works and Economic Adjustment Assistance programs—make capital grants simply too small to fund many infrastructure projects.17

Federal competitive programs suffer from another structural flaw: the focus on awarding funds to single projects. Regional infrastructure deficiencies typically cannot be resolved by one project, even if it’s as large as a new transit line or remade roadway corridor.18 Regions need suites of mutually supportive projects to solve larger challenges, but there is often no straightforward administrative path to bundle together multiple distinct yet interconnected projects for federal fiscal support. In the rare occasions when federal programs do permit project bundling and environmental permitting hurdles unique to bundling are overcome, the results work in favor of regions. For example, regions have competed well under the Safe Streets and Roads for All program because it permits broader bundling of infrastructure (e.g., roads, sidewalks, bike paths and trails, and pedestrian safety mechanisms) in street redesigns. The Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA) allows applicants to submit interconnected clean water and drinking water projects, as is the case in a successful $196 million loan for the Indiana Finance Authority.19

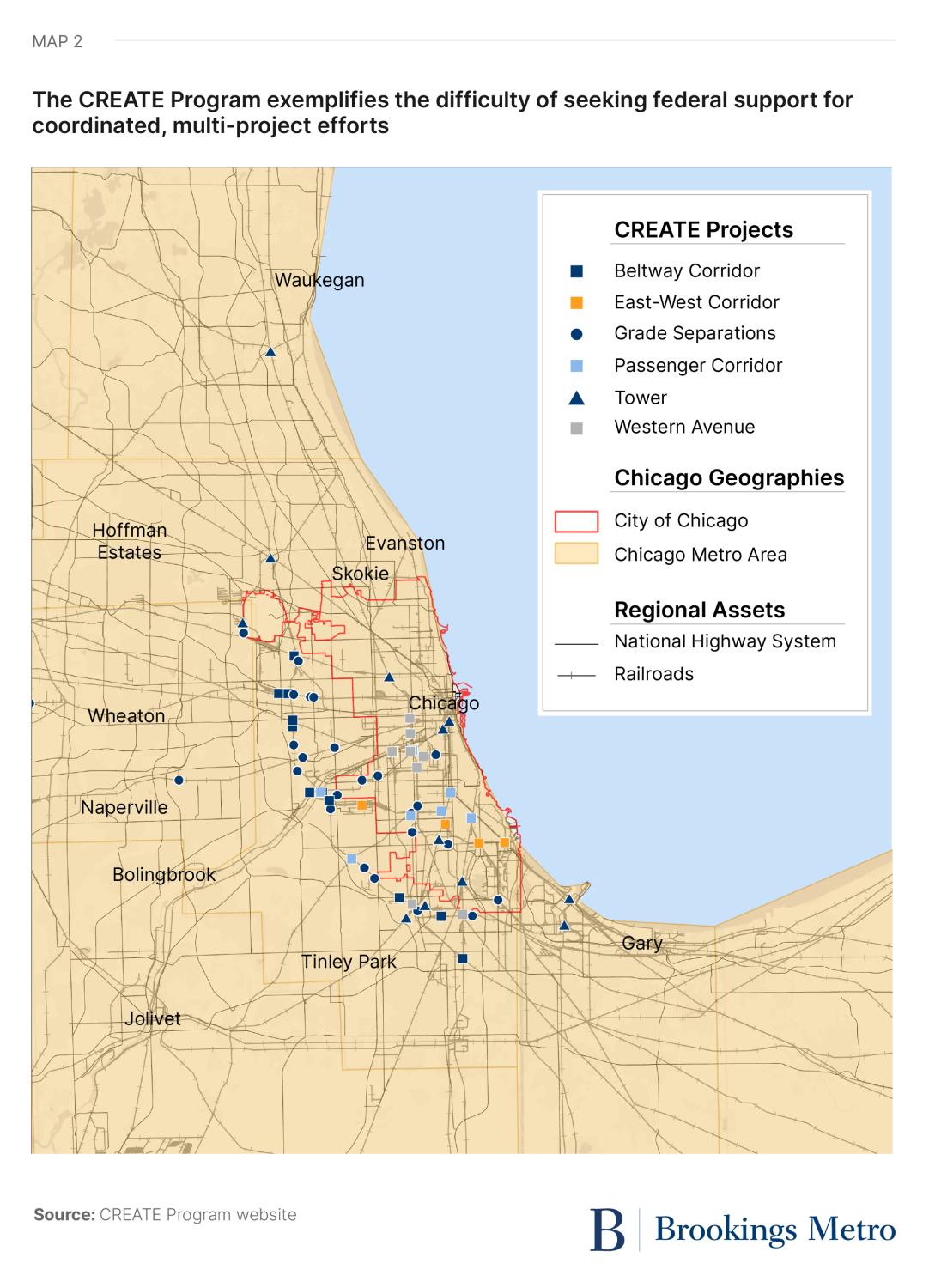

There may be no greater example of how current federal awards fail to adequately support transformative regional infrastructure than Chicago’s CREATE (Chicago Region Environmental and Transportation Efficiency) Program. The program is a public-private partnership that is funding more than 70 projects to improve both freight rail movements and driving conditions by upgrading grade crossings, junctions, and other rights-of-way all across Chicagoland, with far-reaching benefits to local drivers, regional freight and warehouse firms, and all the national trade routes running through the metropolitan area. Every jurisdiction, including city, county, state, and federal, agreed to work together with the private sector. Together, these agencies identified regional transportation priorities that would improve passenger and freight rail in one of the busiest rail networks in the country.

The problem was federal programmatic design: There was no single pool of federal funds that the partners could draw from to support a program with multiple projects over multiple years. Instead, public officials and freight rail firms kept waiting for intermittent federal commitments. The CREATE Program was established to serve as that engine for project generation, receipt of federal funding, and project completion. There are now 34 completed projects and another 19 under construction. That is a relative success, but the progress must be qualified. It took two decades to get this far, with another $3 billion worth of projects still to fund and build. CREATE checks all the transformative infrastructure boxes, but its potential is hemmed in by a network of federal programs ill-suited to support regional or national needs.

Awarding one-off projects incentivizes zero-sum thinking within regions. Neighboring municipalities that could be partners on regional projects—especially ones that are more expensive than any one entity can finance—quickly run to their own corners, designing applications in private and hesitating to share ideas with their regional peers.20 This type of grantmaking environment ends up favoring the highest-resourced municipalities, and evidence confirms their greater relative likelihood to win grants.21 This outcome can be especially problematic if federal officials, seeking parity in funding across geographies, consider an entire region funded when only one city wins an award.

By contrast, planning grants are far more supportive of regional thinking. The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) annually commits around half a billion dollars to metropolitan planning activities. The EDA offers regions relatively small grants to complete Comprehensive Economic Development Strategies (CEDS)—effectively a region-serving, long-run economic plan. ARPA and IIJA each launched new programs to support regional collaboration, with tens of millions of dollars available to winners for more extensive planning work. Oversubscribed interest in programs such as Assistance to Coal Communities, the Build Back Better Regional Challenge, Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs, and Recompete—much like the Sustainable Communities Regional Planning Grants from over a decade prior—confirm local stakeholders are eager to work regionally.

Yet even planning programs miss key opportunities to grow regional collaboration and capital investments. For one, federal planning grants typically do not permit the awarded entity to sub-award funds. Federal program rules also restrict planning dollars from one agency to cover work conducted under another agency’s purview, such as economic development to support transportation planning. In practice, these two restrictions mean an MPO, COG, or CEDS designee cannot use dollars flexibly to cover external partners’ time or to synchronize different planning documents. The restrictions are especially problematic for potential nongovernmental partners, many of which may be instrumental in offering independent thinking and serving as external champions.

Representation on Capitol Hill can also undermine regional cohesion. Odd district geographies can lead members to serve multiple different regions at once, so securing investments that benefit the entire area requires coordination and political will from multiple representatives. Even when a House district is in a single region, it may only contain part of it, so representatives may prioritize wins for their own constituencies rather than the broader region. The Senate is often more straightforward, with senators able to claim credit for all the formula funds their state receives. Of course, even they face barriers when it comes to the many regions that cross state lines, such as Charlotte, N.C., Memphis, Tenn., and St. Louis. Regional coalitions have the extra burden of securing support from several congressional stakeholders, unlike their wholly intra-state and local peers.

The net result is clear: Federal law asks stakeholders to convene as a region, but the same federal programs offer too little funding or flexibility to translate plans into region-serving projects.

Federal program structure could better play to the strengths and weaknesses of regional entities and their municipal peers

While current federal programs directly invest too little in regional-scale infrastructure, current programs are not well suited to directly benefit cities, counties, and other municipalities either. Fortunately, many of the strengths and weaknesses among municipal and regional actors balance the other, particularly between strategy and project delivery. If the goal of federal officials is to more directly achieve many national infrastructure goals, then designing federal capital programs around those complementary abilities is a great place to start.22

Beginning with regions, both government and civic stakeholders bring significant strengths. Regional entities are adept at convening neighboring municipalities and civic stakeholders to exchange concerns, share best practices, and co-design long-term plans. Many regional entities already provide technical assistance to local partners, saving costs for both sides. Federal requirements also have meant staff at MPOs, COGs, water utilities, and CEDS designees are all familiar with federal planning requirements and maintain regular contact with state officials. Regional entities’ staff can—and do—quickly access expertise they may lack through this broad network, such as construction-related permitting and related spending rules.23

The current federal approach to infrastructure funding has weakened regional entities. MPOs and COGs currently control too few dollars to implement their plans to achieve meaningful impact for the region, and many lack the legal authority to raise their own revenues. They may lack the capacity and staff necessary to deliver projects and manage construction. Tight budgets mean the available time from the staff they do have is often limited, even if local partners keep requesting more technical assistance such as project predevelopment and competitive grant writing. These tight budgets also limit the opportunity to experiment with new project designs and financing techniques. Finally, long-term infrastructure and economic development plans often exist in silos, partially due to a lack of state or federal requirements that they integrate with one another.

Municipal strengths can counter many of those regional weaknesses. Municipalities own their infrastructure assets, which gives them control over capital plans. With their ownership comes experience in construction management and project delivery. They tend to have broad revenue-raising authorities and can self-finance future improvements. Localities also have experience working across multiple infrastructure sectors and economic-development-focused entities, from the largest cities with powerful mayors and councils to relatively small places with just a handful of staff.

Yet localities are also significantly constrained, and the constraints disproportionally fall on smaller cities, counties, and other municipalities. Those places tend to have less fiscal capacity to raise revenue or new bond proceeds, limited staff capacity to tackle more projects, and little to no experience administering federal grants or complying with federal accounting rules.24 Even for the biggest markets, project predevelopment is risky if implementation depends on winning a federal or state competitive grant. And all municipalities struggle to learn from local or national peers unless a collaborative partner facilitates the idea exchange.

Federal lawmakers should apply lessons from recent investment laws

Federal lawmakers can design policies that directly respond to these strengths and weaknesses. In doing so, they also should reference the most recent federal investment laws for what kinds of program designs, project selection systems, fiscal models, and implementation approaches worked best for regional and local partners. Based on our interviews and research, four key lessons emerge.

First, federally supported technical assistance is well regarded by both providers and recipients, but funding and delivery methods need to be scaled to meet demand

The IIJA and IRA, in particular, helped federal staff assist more applicants with navigating the federal application process and, later, managing federal funds. By increasing agency budgets, those laws also enabled agency staff to offer more general knowledge transfer beyond federal compliance. Both federal and regional stakeholders found the extra technical assistance (TA) to be effective in building local capacity and improving trust among local stakeholders in their federal peers. The issue was oversubscription: Administering hundreds of grant programs and serving tens of thousands of eligible applicants effectively supercharged TA requests.

Federal lawmakers can learn from this experience. It is worth considering whether federal agencies should focus more time on overall knowledge transfer that naturally scales, including tools such as webinars, helplines, national events, and cohort learning models. One successful example is the EPA’s new Climate Resilience and Adaptation Funding Toolbox (CRAFT), which serves as a central meeting point for multiple programmatic needs. The National Science Foundation (NSF) also stood up the Regional Innovation Engines program, which is set up to stoke knowledge sharing across academia, industry, the public, and nonprofit sectors to drive economic growth in previously under-performing regions. Congress and agency leadership can also find ways to centralize TA services, reducing the overall staffing burden and streamlining the amount of recipient touchpoints. A notable example is the new single application process used by the Department of Transportation (USDOT) for three different programs. Or, agencies can empower regional leaders to act as capacity builders for local cohorts, such as in the Thriving Communities Program. Finally, it is clear that the federal government can delegate more TA down to state and regional government staff and include additional funding to cover their time, given the preeminent importance of assistance attuned to state and local laws.

Second, municipalities and other local governments can spend federal funds efficiently when funds are predictable and rules are clear

The main takeaway here is that municipalities could manage federal dollars as efficiently as their state-level peers—they just need to be given the opportunity to build the capacity through consistent and predictable funding streams over multiple years. This affirms the general experience among states, which have built muscle memory through long-standing federal commitments and relationships. If the incentive is ultimately more federal funding, one can expect municipalities will keep building their federal compliance acumen and coordination. Since federal programs reimburse awardees relatively quickly, experts we interviewed noted that stable funding enhances administrative capacities and helps places achieve their goals more efficiently. Reasonable controls would also help give federal lawmakers confidence that regional recipients—and their sub-awardees—can safeguard against waste, fraud, or abuse of funds.

The past four years give us evidence to support this expectation. ARPA’s Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds (SLFRF) sent $130 billion directly to localities and gave recipients multiple years to choose projects and commit funding.25 SLFRF has many flexible uses, including multiple infrastructure, community development, and other built environment improvements. Per Brookings analysis, large cities and counties leveraged SLFRF’s flexibilities to extend the reach of complementary IIJA and IRA programs. Per the most recent accounting at time of publication, localities spent their funding at the same rate as states, and their obligation rates were not far behind. While the program has political detractors, one cannot deny the speed by which localities demonstrably expended their funds.

Third, municipalities will come together around regional investments when federal programs prioritize regional thinking from the onset

While representing only a small subset of programming under ARPA, IIJA, and IRA, the three laws launched multiple programs that explicitly required regional designs and collaborative applications to land significant federal funding. Consistent oversubscription in these programs is a clear market signal that: 1) localities are willing to both bundle projects together and support one another; and 2) federal funding can incentivize them to do it. Experts were especially impressed by how localities responded to the call for interdisciplinary thinking, such as within the EDA’s Build Back Better Regional Challenge. Flagstaff, Ariz. offers another example, where a local coalition developed a Federal Grants Strategy to better position themselves for competitive funding.

Fourth, regions with high civic cohesion can deliver regionally important projects

Our interviews revealed a subtle but profound knock-on effect regarding personal relationships and trust. The application process for competitive grants effectively required local stakeholders to build and strengthen relationships with one another and, importantly, new cohorts of local government, civic, philanthropic, and business leaders. For grant winners, landing funds created a positive feedback loop to keep collaborating. But failing to win funds made it harder to nurture those same relationships. The upshot: If federal programs can reach all regions, federal lawmakers can be confident they will benefit as much in civic cohesion as they will in physical projects across a region.

Regional block grants can address multiple shortcomings in current federal policy

Federal lawmakers are focused on investing in America, but currently policy fails to empower America’s regions to address cross-jurisdictional needs. Delivering funding directly to regions will boost staff capacity and reduce fiscal pressure, accelerate delivery of capital improvements across multiple asset classes, and give regions room to try new solutions to structural issues. The bottom line is this: Regional block grants are ideally suited to address regional needs and outdated federal policy design.

To start, federal, state, and local officials are all looking for greater efficiency of fiscal transfers accompanied by safeguards against fraud and abuse. The enormous increase in competitive grant programs funded by ARPA, IIJA, and IRA have overtaxed federal evaluators, applicant teams, and TA providers. Many municipalities that won awards suddenly had to learn federal compliance rules, which required further educational support from their federal, state, and regional colleagues.26 Regional block grants could be purposely designed to greatly reduce the administrative burden and guarantee certain annual funding to entire regions, which can then suballocate funding to member jurisdictions and serve as centralized compliance support.

Block grants can help address the breakdowns between different planning and investment programs, in this case by permitting cross-disciplinary activities. Regional governments already bring together a broad suite of government, business, and civic actors to prepare multiple long-term plans. By offering flexible planning funds, a regional block grant program can permit MPOs and COGs to shift planning dollars across currently atomized exercises, including within economic development, housing, transportation, and natural resources. Similarly, each block grant’s capital funding pot can be flexible enough to fund projects across different sectors that advance shared regional goals, such as the energy and transportation projects that address Comprehensive Economic Development Strategies. This integrated approach ensures that projects align with long-term regional goals and foster innovation and sustainability within the region, all while allowing federal lawmakers to bundle multiple permissible (and prioritized) uses within one program.

Block grants also provide the kind of multiyear, durable funding streams that regional governments, municipalities, and their civic partners are seeking. The recent push into competitive grantmaking offered localities more opportunities to directly access federal funds. But the unpredictability of which applications may win left stakeholders questioning the time and resources that went into unsuccessful efforts and whether what they did win was actually the best and highest use of federal funds. Regional block grants can continue the direct delivery of federal funds to regions and split funds between guaranteed awards to all members, reserving a pot for more region-serving, competitive ideas. Knowing that a regional funding pot exists would make predevelopment less risky, encourage localities to initiate new projects, and generally promote deeper collaboration and trust-building among neighboring jurisdictions. No community ever has the exact same vision for a region, but the block grant concept bets that offering significant capital funding can promote collaboration and compromise.

Smaller municipalities and regions struggle with capacity constraints compared to their larger peers, and a block grant can also address that deficiency. An regional block grant can be designed to use state-level expertise to support growth in the smallest regions by establishing either a “regional center of excellence” or supplementing a similar office that already exists. TA resources can thereby be allocated to those sub-regional partners as needed. Those offices can also co-manage regional block grant funds with lower-capacity places and offer advice to peer agencies managing previously established federal grant programs such as the CDBG. Increasing dollars specifically for administrative costs can tackle these capacity issues directly. Critically, a regional block grant doesn’t touch states’ core role—managing their own assets and supporting their local peers—by ensuring transferability of funds when regions select projects on state assets.

Administering a block grant can accelerate experimentation and national learning too. Localities, regions, and states are always looking to learn more from one another, but they rarely have the bandwidth to build those external relationships as they prioritize what is required in their own backyards. Since any regional block grant would reduce administrative burdens and compliance requests, the federal agencies where regional block grants are administered could focus their resources on collecting national experiences and sharing lessons with other communities. One of the great benefits of block grants is the flexibility they bestow on recipients to pursue bespoke and innovative ideas generated at the local and regional level. Federal staff are well positioned to socialize the lessons such flexibilities offer.

Finally, new block grants can purposely address some of the critiques of older programs. For example, lawmakers should standardize reporting around project selections, ensuring recipients do not overlook communities based on economic need, voting records, or other biased criteria. Using noncompetitive distributions ensures all regions stand to benefit, irrespective of region-state relationships.27 Congress must strike a balance between ensuring these long-standing issues are addressed and keeping compliance costs for regions low. A regional block grant should also use objective performance criteria around project selection and evaluating impacts, and federal agency officials should be required to report back to Congress with their assessment of national patterns.

Even with a strong theoretical case, congressional policymakers will need to thoughtfully consider several dimensions to maximize the effectiveness of regional block grants. Bill writers must weigh possible recipients, whether to require a local match or provide a bonus for obtaining one, and how to ensure technical assistance reaches those places that currently lack capacity. Federal law will need to be clear on which project types and asset classes will be qualified to receive federal support. Lawmakers may also need to give clear authority for regional governments to raise own-source revenue. Perhaps most obviously, lawmakers will have to decide exactly how much money to dedicate to each of the nation’s regions, and how to define them geographically or by population. Elected officials and their staffs will certainly want different designs depending on the infrastructure sector.

Using surface transportation to pilot regional block grant principles

A transportation-focused regional block grant program would fill a known gap within the federal transportation program. From a 1986 GAO report to a 2024 Congressional Research Service report, federal institutions formally recognize two interrelated truths. One, regions are not receiving their share of gas tax contributions due to apportionment formulas. Two, the buildout of the Interstate Highway System raises new needs in more populated places. The Surface Transportation Block Grant program launched in 2015 proves asset flexibility is possible, but that program still gives states primary control over funding.

A regional block grant could build on that model by delivering significant funding directly to regions, leveraging pre-established laws spread across Titles 23 and 49 in the United States Code that specify a direct federal relationship for metropolitan planning organizations. The block grant could be a newly apportioned pot or carveout within a current formula program, either of which would be specified in the next authorization set for November 2026. See our more complete proposal for such a transportation program.

Conclusion

America’s regions face many barriers to providing and maintaining infrastructure that supports their prosperity. Regions can break past those barriers with the help of regional block grant programs.

From metropolitan New York to the smallest urban hamlets, every region now publishes multiple long-term plans that set out tangible goals to deliver economic prosperity. The federal government should go beyond incentivizing such plans—it should also bring serious funding to help construct the regionally significant projects that will bring those plans into reality. The next big steps are for lawmakers and their staffs to explore the idea, debate alternatives, and advocate for a path forward within established authorizing legislations. It’s time to take those steps.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

This research series was made possible by an incredible group of colleagues within and outside the Brookings Institution and the Policy and Innovation Center. The authors would especially like to thank the 21external experts who were willing to be interviewed for this project. The authors would also like to thank all the individuals who provided thoughtful reactions and recommendations to a draft version of this report, including (but not limited to) Scott Andes, Bethia Berke, Alan Berube, Joe Bost, Travis Cone, Matthew Dalbey, Katie Economou, Joseph W. Kane, Bill Keyrouze, Michael Pagano, Samantha Silverberg, Wendi Wilkes, Mariia Zimmerman, and Erich Zimmermann. Finally, the authors thank Michael Gaynor for editing, Carie Muscatello for her web and print design, and the rest of the Brookings Metro communications team for their support.

The Brookings Institution would like to thank the Kresge Foundation and the San Diego Foundation for their generous support of this work. Brookings Metro is also grateful to the Metropolitan Council, a network of business, civic, and philanthropic leaders that provides both financial and intellectual support to the program. The Policy and Innovation Center extends their appreciation to the multiple funders within and affiliated with their institution that supported the successful completion of this work. The views expressed in this report are solely those of its authors and do not represent the views of the Brookings Institution and the Policy and Innovation Center’s donors, their officers, or employees.

-

Footnotes

- At the time of writing, Congress had not rescinded any appropriated funds from the IIJA or IRA. Ongoing conversations among lawmakers signal that they are considering a rescissions package for grant programs. However, 19 Senate Republicans voted in favor of the IIJA (Sen. Mike Rounds [R-S.D.] was absent, but as a member of the informal “gang” negotiating the legislation, would have voted in favor as well), making the enactment of an IIJA rescission package—even at a bare majority threshold—unlikely.

- Brookings research on state departments of transportation found that most states do not publicly connect their long-range goals to the projects they select. Similar research on State Revolving Funds (SRFs) found that 47% of Clean Water SRFs and 61% of Drinking Water SRFs do not provide distinct, public-facing lists of prioritized projects.

- Ibid.

- American Society of Civil Engineers’ 2025 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure and 2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure.

- This is as reported by the Federal Highway Administration’s 2022 Highway Statistics, and includes data since 1967.

- Federal Highway Administration’s Highway Statistics 2022, Table DISB-C.

- The sole subject of this research is urbanized areas, including metropolitan and micropolitan areas. We do not assess the needs of federal multistate regions and their administrative counterparts such as the Delta Regional Authority and Southwest Border Regional Commission, many of which provide valuable infrastructure services to both urban and rural areas.

- Literature highlighting common policy areas of collaboration between local government and regional entities include: land use and transportation planning (e.g., Amini et al., 2021; Lowe et al. 2016; Lowe & Sciara, 2018; McAslan et al., 2024; Pendall et al., 2013; Sciara & Handy, 2013; Walsh et al., 2024; Weir et al., 2009; ), economic development (e.g., Drabenstott, 2005; Fitzgerald, n.d.; Lee & Lee, 2022), emergency response or preparedness (e.g., Crow et al. 2018; Schwab, 2010), and energy or climate issues (e.g., Park et al., 2019; Youm & Feiock, 2019).

- Councils of government use many names across different states, including area planning agencies, regional councils, and regional planning commissions.

- While not directly associated with infrastructure, regional economic development groups have also been found to raise personal incomes and employment growth in more politically fragmented metro areas. See: Chen, S. H., Feiock, R. C., & Hsieh, J. Y. (2016). Regional Partnerships and Metropolitan Economic Development. Journal of Urban Affairs, 38(2), 196–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12183.

- For a prominent example, see the Regional Plan Association’s multi–decade commitment to long-range visioning for the New York metropolitan area, currently in its fourth version.

- In addition to links found in this paragraph, other research includes: Deyle, R. E., & Wiedenman, R. E. (2014). Collaborative Planning by Metropolitan Planning Organizations: A Test of Causal Theory. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 34(3), 257-275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X14527621; Myron Orfield, Metropolitics, Brookings Institution and Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 1997.

- See Park, A. Y. S., Krause, R. M., & Feiock, R. C. (2019). Does collaboration improve organizational efficiency? A stochastic frontier approach examining cities’ use of EECBG funds. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 29(3), 414–428. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muy078 and Toepler, S., & Abramson, A. (2021). Government/foundation relations: A conceptual framework and evidence from the U.S. federal government’s partnership efforts. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 32(2), 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00331-z.

- For examples, see Bickers, K. N., & Stein, R. M. (2004). Interlocal cooperation and the distribution of federal grant awards. The Journal of Politics. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2004.00277.x and Shah, A. (2012). Grant financing of metropolitan areas: A review of principles and worldwide practices (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 2026806). https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2026806.

- The proceeds from these loans then “revolve” within the SRFs. The intent of this approach was to gradually reduce the need for new infusions of federal funding; however, the programs have proven popular enough to have received consistent appropriations, most recently funded to record levels through the IIJA.

- Source: Interviews with external experts.

- The concept of “braiding” is introduced by Stoker and Rich (2020): where agencies are encouraged to seek multiple sources of financial support across sectors or levels of government and to “coordinate the use of resources across multiple policy domains.” Braiding, while well intentioned, appeared to add “another level of complexity to an already complicated process”.

- For two relevant examples, see: Lowe, K., & Sciara, G.-C. (2018). Chasing TIGER: Federal Funding Opportunities and Regional Transportation Planning. Public Works Management & Policy, 23(1), 78–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724X17732583; Stoker, R. P., & Rich, M. J. (2020). Obama’s Urban Legacy: The Limits of Braiding and Local Policy Coordination. Urban Affairs Review, 56(6), 1607–1629. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087419849490.

- U.S. EPA (2025, February 3). Indiana Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Projects. https://www.epa.gov/wifia/indiana-water-and-wastewater-infrastructure-projects.

- Source: Interviews with external experts.

- For examples, see: Hall, J. L. (2008). Assessing Local Capacity for Federal Grant-Getting. The American Review of Public Administration, 38(4), 463-479. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074007311385.

- Federal goals for collaboration include facilitating regional competitiveness, breaking down silos at the federal or regional level, and directing resources to disadvantaged communities and stakeholders not previously involved in regional planning efforts.

- Source: Interviews with external experts.

- Mattson, Gary A., and Paul L. Solano, “New Federalism and Small Towns: Do Planning-Management Skills Matter for Access Funding and Benefits?”, Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 3, no. 2 (1986): 133–47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43028796; Shah, A. (2012). Grant Financing of Metropolitan Areas: A Review of Principles and Worldwide Practices (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 2026806). https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2026806.

- The remaining SLFRF funding flowed to tribal governments and U.S. territories.

- The law’s authors and the Biden administration did add additional compliance requirements for certain programs, which added extra compliance for those program’s awardees.

- Brian K. Collins, Brian J. Gerber, Redistributive Policy and Devolution: Is State Administration a Road Block (Grant) to Equitable Access to Federal Funds?, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Volume 16, Issue 4, October 2006, Pages 613–632, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muj010.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).