Social Security faces a big hole in its finances. The program takes in too little money to pay for its long-term obligations. Last year it saw nearly $860 billion go out the door to pay for benefits and administration. Its dedicated tax revenues covered only 91 percent of that amount. Fortunately, the program continues to hold large reserves, built up in past years when revenue was greater than pay-outs. As more of the baby boom generation retires, however, spending will rise faster than income, and program reserves will start to shrink.

According to government forecasts, the reserve fund will be depleted in less than 20 years. At that point the dedicated revenues available to fund Social Security will cover a little less than 80 percent of promised benefits. If Congress does not change the law before 2034, benefits will have to be cut about 20 percent when the reserve is used up.

One way to deal with the problem is to raise the Social Security retirement age. Advocates of the idea usually argue the reform makes sense because life spans are rising. If we leave the Social Security retirement age unchanged, the increase in life expectancy means payments from the program must cover more years, even though the number of years we expect workers to remain employed will remain unchanged. This argument would be more convincing if increases in life expectancy were spread evenly across the workforce. They are not. Workers who earn low wages throughout their careers have seen little or no improvement in life expectancy. It seems unfair to ask low-earners to take a benefit cut to pay for the added benefits high-earners enjoy because of longer life spans.

Recipes for hiking the retirement age come in many flavors. The simplest is to delay the age at which workers can claim a full Social Security pension. For workers currently in their mid-60s, the full retirement age is 66. For workers born in 1960 and later years, the full retirement age is already scheduled to increase to 67. Most proponents of a higher retirement age think the full retirement age should be gradually raised for people born after 1960 to 68, 69, or 70.

If the full retirement age were increased to 68, workers wouldn’t have to wait any longer to collect their pensions. They could still claim a benefit starting at 62, as they can today. However, their monthly check would be 6% to 7.5% smaller than promised under the current formula, depending on the age when they first claim a pension. We raised the retirement age for Social Security recently, so we can learn from that experience. The full retirement age was increased from 65 to 66 starting in 2000. Looking at those who turned 62 that year, research shows that some who were affected by the higher retirement age worked a bit longer, some delayed claiming a pension, and some did both. Workers who delay claiming Social Security for one additional year, say, from 63 to 64, after the full retirement age is raised from 67 to 68 would see little change in their monthly pension, but would receive it for one less year The delay seems fair if the worker has enjoyed the same improvement in life expectancy as fellow workers. It doesn’t seem so fair if the worker has seen little or no gain in life span.

It’s easy to identify a group that has missed out on recent life expectancy gains—workers who earn low wages throughout their careers. Researchers in the Social Security Administration and elsewhere have found that men near the bottom of the earnings distribution and women with below-average schooling and in families with low incomes have seen little or none of the improvement in life expectancy that higher income groups have enjoyed.

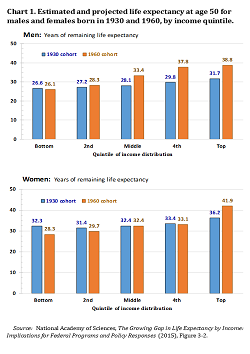

Low income workers always had shorter life expectancies than workers with higher incomes. New research shows that the gaps in life expectancy are growing. The chart shows estimates prepared by a committee of the National Academy of Sciences of the remaining life expectancy of men and women born in 1930 and in 1960. The projections show the expected remaining years of life of people in these cohorts when they were 50 years old. The bars on the left show projections for men and women in the bottom one-fifth of the income distribution, while the bars on the right show estimates for men and women at the top of the distribution. These new estimates indicate that life expectancies are typically higher for men and women with higher incomes, but that remaining life expectancy at age 50 has remained almost unchanged or fallen at the bottom of the distribution, whereas it has increased substantially at the top.

A key goal of Social Security is to ensure that workers who have contributed to the program throughout their careers enjoy decent pensions and a dignified retirement. Any change in the program to keep it solvent should assure workers with low lifetime wages that they will receive a decent pension even if they retire at today’s early retirement age. Since these workers have not benefitted from the life span improvements most of us have enjoyed, it would be unfair to expect them to work longer to qualify for a decent pension.

Editor’s Note: A version of this post originally appeared in

The Dallas Morning News

.

Commentary

Op-edRaising everyone’s retirement age undercuts a key goal of Social Security

October 22, 2015