I am deeply honored to receive this award for Leadership Excellence from the Economic Club of New York. This Club brings together the best minds of the economic and financial community of the world’s preeminent financial center to discuss serious subjects—stuff like the future of the world economy—with thought leaders from around the world. Award ceremonies always make me cringe a bit, because they force the awardee to listen to her own obituary. But this one comes with a big benefit—in addition to a nice check. It creates the opportunity for me to say what I think Americans need to do to put our economy on a track to sustainable broadly shared prosperity—and say it to an audience with lot of power to make it happen. So I want to take maximum advantage of that opportunity.

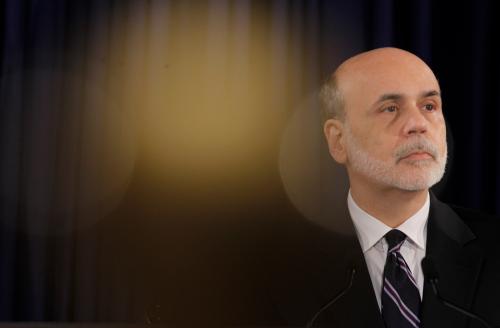

My long career has given me the chance to participate in economic policy making on Capitol Hill, in the White House and at the Federal Reserve. That gives me a bit of license to opine about monetary, fiscal, and regulatory policy and the intersections among them. All are important to our economic future and there is a lot more to be said about each than we have time for over lunch. So today I would like to say a brief word about the state of monetary policy and financial regulation and then try to focus your attention on what we need to do to make budget policy useful again. That emphasis reflects my view that budget policy is the most broken part of economic policy, poses the most dangers for the future of shared prosperity, and could be most constructively influenced by the people in this room.

I know many of you spend a lot of time worrying about when the Fed will raise interest rates and what the ECB is up to, which is not surprising because monetary policy affects your bottom lines immediately and directly. But from a broader economic policy perspective monetary policy should be far down our list of worries. Monetary authorities proved themselves remarkably competent in managing through the crisis once it happened and keeping recovery going despite fiscal austerity. Given the current medium term outlook for the major developed countries, monetary policy is highly likely to remain accommodative for a good long time. Our own economy is growing moderately well, but there is still slack in labor and other markets. Unemployment rates have come down to near tolerable levels, while the ratio of people with jobs to the working age population remains frustratingly and somewhat mystifyingly below par. The rest of the world is in far less robust shape than we are. Inflation is below target in all major developed countries, and unlikely to accelerate any time soon. The consequence of this set of circumstances is that low interest rates will be appropriate monetary policy for the foreseeable future. That doesn’t mean the Fed won’t raise rates at some point—just that they won’t go back to anything like the old “normal.” Central banks are going to be stuck with managing large balance sheets and preparing tools to down size them carefully, if and when we should be lucky enough to see the stronger growth and tight labor markets that could revive inflation as a future threat.

This prospect of sustained low interest rates makes financial regulatory policy even more crucial than it would otherwise be. Indeed, the imperative of getting financial regulation right is hard to exaggerate. The most important objective of economic policy is to keep anything close to the catastrophe of 2008 from happening again. Dodd Frank has given us a much-needed set of new tools to enhance financial stability and resolve insolvent financial institutions in ways that contain contagion. But the new tools have not yet been refined or tested. Nor can we be sure that the authorities will have the political will to use them at the crucial moment. Moreover, Dodd-Frank did little to rationalize our cumbersome, fragmented regulatory structure, which is the next big challenge we need to tackle. The Volcker Alliance’s report, Reshaping the Financial Regulatory System; Long Awaited, Now Critical, released yesterday, maps out a bold restructuring of the regulatory apparatus to get responsibilities clearer and reduce regulatory arbitrage. The report is aimed at starting serious conversation about how to make our financial regulatory system simpler and more effective.

So I don’t think we should worry much about monetary policy. It is in competent hands at the Fed, the ECB, the Bank of England and other central banks, and they seem to be getting it just about right. Unfortunately, monetary policy, without complementary fiscal policy, has never been a very effective tool for generating robust growth. Financial regulation is much more of a work in progress, but moving slowly in the right direction. Budget policy, however, is a total disaster in danger of getting worse.

Budget policy is a disaster because it is the province of our deeply broken legislative system. The ability to compromise and solve problems across party lines is essential to making a budget and this ability has failed us just when we need it most. In a persistently slow growth economy where monetary policy is likely to be relatively ineffective, pro-growth fiscal policy could actually help.

To the extent that there has been anything that could be described as budget policy in Washington for the last three or four years, it has been counterproductive. The stimulus enacted in 2009 did help turn the economy’s free fall into a slow but fairly steady recovery, reinforcing both the automatic stabilizers in the budget and aggressively easy monetary policy. But once the stimulus was spent and the economy began to recover, deficits plummeted and fiscal policy turned restrictive. The Fed found itself struggling to keep the recovery going in the face of fiscal currents pushing in the opposite direction. It is testimony to the Fed’s persistence and the inherent resilience of the American economy that the recovery has been as strong as it has.

Moreover, much of the budget austerity was mindless across-the-board cuts in so-called “discretionary spending.” That is the annually appropriated part of the budget that keeps the essential wheels of the government turning and funds investment in future growth—like basic research, building skills, and modernizing infrastructure. Discretionary spending was not the part of the budget that was growing most rapidly before the austerity set in. Nor was it expected to grow much in the future. It was entitlements—especially Medicare, Medicaid, and to a lesser extent Social Security–that dominated projected federal spending. But it was far easier to cut discretionary spending, because it could be done by lowering aggregate spending caps did not require revealing what specific spending would actually be reduced. It was politically relatively painless.

The sharp polarization of politics and ideology has turned debate about federal activities and their funding into vapid generalities and name-calling. Republicans generalize that federal spending is wasteful, harmful, too big, and should be cut. Democrats say the government isn’t doing enough and any cuts will do incalculable harm, especially to poor people. Republicans decry all taxes; Democrats argue for higher taxes on the rich. Each side demonizes the other’s motives and no constructive dialogue ensues.

I believe the New York financial community, with its huge stake in the performance and vibrancy of the American economy, can do a lot to change the conversation about the role of government. First, we need to break out of the ridiculous debate about whether the federal government spends too much or too little and focus on the specifics of what we want the government to do, how to do it well and how to pay for it. With confidence in all institutions, public and private at low ebb, there is no point in trying to restore confidence in government in general. A better tactic is to focus first on selected activities that almost everyone needs the government to do competently.

I don’t think it would be difficult to get agreement on a list of basic activities that most politicians and most citizens want done competently. We want to secure the borders, make sure airplanes don’t crash, get passports issued, make going to a national park a safe, pleasant experience, have competent, fair law enforcement, etc. Further down the list things get more controversial, but it would be a big advance to get the non-controversial activities adequately funded without so much drama. And I suspect the list of non-controversial activities may be quite long. Even people who would like lower taxes want the tax laws fairly enforced. What sense does it make to have the IRS too strapped to answer tax-payer questions or audit returns of likely tax cheats? Do we really want Medicare wasting money because it can’t afford to prosecute fraud?

Second, with slow growth inhibiting shared prosperity, we need to make the case for shifting federal spending—at the margin and over time—toward productivity enhancing public investment and away from lower-priority consumption. But we won’t sell this strategy to a skeptical public or a dysfunctional political system by arguing for more public investment (or even more infrastructure) as a general principle—that just sounds like more spending. Advocates will have to show what improving transportation in a particular area could do to commuting times and commercial costs or what training workers with special sets of skills could do to enhance productivity and competitiveness of specific industries.

And they have to show that reducing low-priority consumption doesn’t mean throwing granny off the cliff or starving poor children. Reducing consumption can mean gradually restructuring entitlement programs, such as Medicare and Social Security so that benefit those who need them most and are less generous to those who need them less. This is especially true of the entitlements in the tax code (like home-ownership subsidies and untaxed employer benefits) that go primarily to people who don’t need them very much. Converting the home mortgage deduction to a credit with an upper limit, for example, could help a lot more middle-income people with their mortgage payments, although it would provide a less generous subsidy to high-end housing.

Third, we need to do all this in a fiscally responsible way, which means gradually bringing the ratio of debt to GDP back to levels that will not inhibit constructive policies in the future. I proudly plead guilty to what Paul Krugman calls, “Simpson-Bowlesism,” although I prefer to think of it as “Domenici-Rivlinism,” after the second of the two bipartisan debt commissions on which I served in 2010-11. Domenici-Rivlinism doesn’t mean austerity that endangers recovery—indeed, we proposed bigger stimulus at the time—or mindless budget balancing at the wrong moment. It does mean moving the budget onto a sustainable path over time and bringing the debt to GDP ratio down. While there isn’t there isn’t any exact point at our debt to GDP ratio becomes dangerous, the fact that this ratio has doubled since just before the financial crisis should make us nervous, mostly because it will make it much harder to mount an effective fiscal response to another recession.

Domenici-Rivlinism doesn’t mean any more discretionary spending cuts. We have gone too far in that direction already. It does mean reforming our tax code to broaden the base and lower the rates. This could give us a tax system that is more progressive, more conducive to growth, and raises more revenue. It also means restraining future entitlement expenditures (including tax expenditures) so that they help low-income people more and upper income people less and don’t grow faster than the revenues needed to support them.

Many people in this room talk to candidates and give them money. You are in a position to make clear that you expect them to stop mouthing off about government being too big or all cuts being unconscionable and start thinking sensibly about what we actually want government to do, how to do it well, and how to pay for it. You can tell them you expect them to stop posturing and work together to solve problems when they get elected.

Just because I am suggesting you urge candidates to be more discriminating in their attacking and defending government activities, does not imply that I applaud the way we finance campaigns or the way money influences politics. The judicial argument that political contributions are free speech seems far- fetched to me and I would love to see that notion disappear—by constitutional amendment, if necessary—and be replaced by public funding. But that isn’t going to happen quickly. As long as you have this power, I hope you will use it to start a more constructive conversation about how government can enhance our shared prosperity and how to pay our public bills responsibly.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Priorities for economic policy

April 21, 2015