Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

What does India think? This is a question that those of us who work on policy issues outside of government are often expected to answer. A country as big and diverse as India is naturally home to a wide variety of views. Often, we tend to reflect the positions of our peers, or what we read and see in the media. It is also easy and tempting to let one’s personal biases come in the way of any assessment of the mood of the nation.

For this reason, the recently-released public opinion survey by the Pew Research Center is important. Unlike most surveys, Pew conducts face-to-face interviews with some 2500 people from across India each year. This makes their results a much more accurate reflection of Indian public sentiment than, say, spot polls conducted online or surveys done only in major metropolitan centres. For example, unlike many others, Pew accurately predicted Narendra Modi’s landslide electoral victory in 2014.

Quality surveys are important because they help policy elites in New Delhi and elsewhere escape their little bubbles and transcend short-term, media-driven narratives. What, then, can we discern from the latest Pew survey? In my mind, five results are particularly surprising or noteworthy.

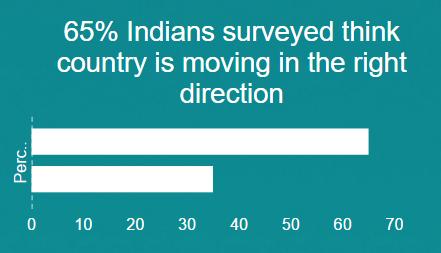

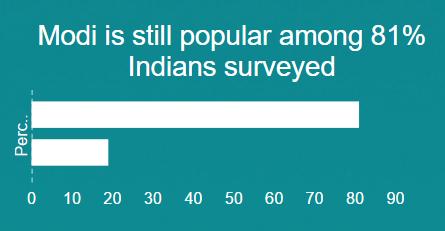

First, Prime Minister Modi’s popularity remains very high at 81 per cent. But what is more unexpected is that a far higher number of Indians think the state of the Indian economy is good: 80 per cent compared with 74 per cent in 2015 and 64 per cent in 2014. Additionally, far more Indians believe that the country is moving in the right direction: 65 per cent this year compared with 56 per cent in 2015 and 36 per cent in 2014. Despite all the justifiable frustrations with the pace of change among many commentators, the government should be heartened by these findings – although they should not lead to complacency.

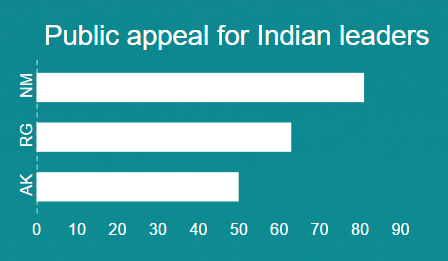

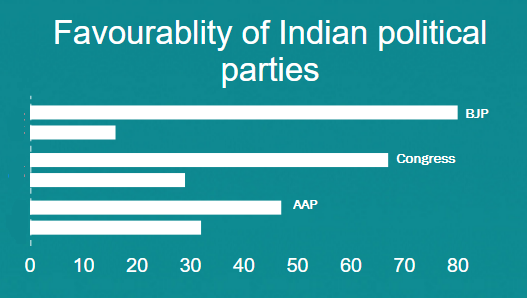

The second surprise concerns the popularity of political parties and their leaders. Public views of the BJP and Congress are generally favourable. 80 per cent have a favourable view of the BJP in contrast to 16 per cent who do not, while 67 per cent like the Congress party compared with 29 per cent who do not. But the numbers for the insurgent Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) are far less encouraging, with 47 per cent in favour and 32 per cent against.

The high unfavourability rating for AAP is particularly surprising given that the majority of Indians have never been governed by the party, and that it is supposed to represent a breath of fresh air in Indian politics. Moreover, the public appeal of Arvind Kejriwal has declined sharply since last year to 50 per cent, compared with 63 per cent for Rahul Gandhi and 81 per cent for Modi. This suggests there are limitations to AAP’s brand of protest politics.

Third, while the Indian public has a high opinion of Modi’s handling of most policies – both domestic and foreign – they are particularly dissatisfied with his handling of Pakistan, with 50 per cent disapproving of his approach towards that country. Presumably, such dissatisfaction has increased over the past few months since the Pew poll was conducted, particularly following the Uri attack. However, some of the dissatisfaction might have been mitigated by the prime minister’s mention of Balochistan in his Independence Day speech, and the signal that sends.

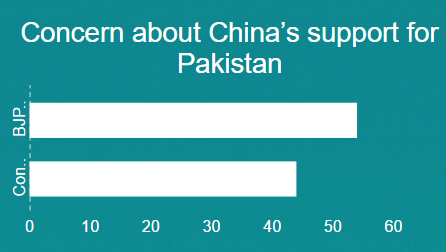

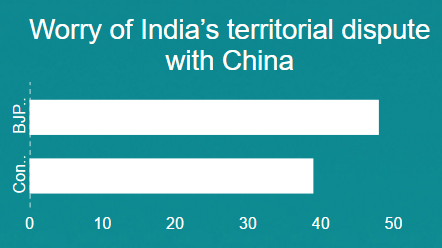

Fourth, while public opinion is generally wary of China, perspectives are sharply divided along partisan lines. For example, 54 per cent of BJP supporters are concerned about China’s support for Pakistan, compared to just 44 per cent of Congress supporters. Similarly 48 per cent of BJP backers worry about India’s territorial dispute with China, compared with only 39 per cent of those supporting Congress. This suggests that forging a national consensus on India’s China policy could be challenging in the coming years.

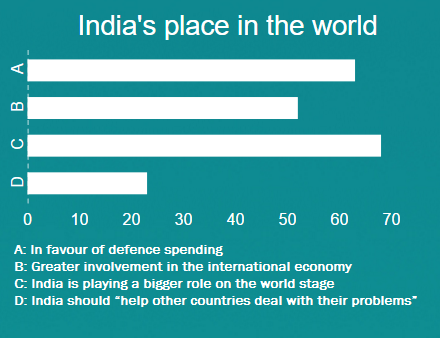

Finally, it is noteworthy that Indians seem conflicted about the country’s global role. The survey reveals that average Indians are very much in favour of defence spending (63 per cent) and greater involvement in the international economy (52 per cent), and they believe overwhelmingly that India is playing a bigger role on the world stage (68 per cent). However, they do not yet believe that Indian power should be used to “help other countries deal with their problems” (23 per cent). But perhaps these views – both pride and caution about a greater international role – are normal for a rising power such as India.

The latest Pew Research survey was launched in New Delhi on the Brookings India platform. Watch a short video by Bruce Stokes, Director at Pew Research, on the major findings of the survey.

Watch also the full playlist of the launch event and audience Q&A at Brookings India, New Delhi

Complete unedited transcript of the discussion

This article was first published in Times of India on Thursday, 22 September 2016. Like other products of the Brookings Institution India Center, this report is intended to contribute to discussion and stimulate debate on important issues. The views are those of the author(s). Brookings India does not have any institutional views.

Commentary

Op-edPew survey results heartening for government but should not lead to complacency

Times of India

September 22, 2016