This paper was revised in October 2016. The most recent version is the one available for download on this page.

Relative to the size of the economy, U.S. federal debt is larger now than at any time since the end of World War II. Under current policies, the debt is expected to climb from around 75 percent of the Gross Domestic Product today to over 120 percent by 2040, and keep growing after that. Debt is rising in part because of a major demographic shift as the baby boom generation retires. It is projected to occur even though interest rates on Treasury borrowing likely will be persistently lower than historic norms.

In a new paper, “Federal budget policy with an aging population and persistently low interest rates,” Douglas Elmendorf, Dean of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard, and Louise Sheiner, Policy Director of the Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy at Brookings, analyze how these and other developments should affect the optimal debt path going forward.

The authors conclude that tax increases or spending cuts will be essential eventually because federal debt relative to GDP cannot increase indefinitely. They argue that restraining the debt is necessary to give the government room to maneuver if a crisis of any sort occurs. In addition, they observe that the aging of the U.S. population, which lowers the fraction of the population that is working, requires reducing future standards of living below what they would be if the U.S. weren’t an aging society.

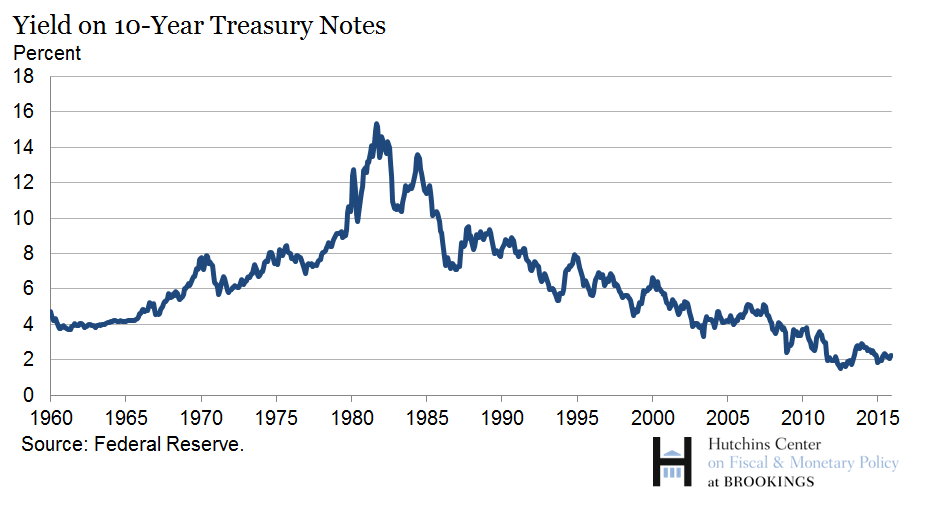

How much and how quickly should the federal government tighten its belt? The authors note that, while debt should eventually decrease relative to GDP, the fact that U.S. government borrowing rates are at historical lows and likely to stay low for some time, implies spending cuts and tax increases should be delayed and smaller in size than widely believed. Low long-term interest rates (see chart) mean that the U.S. should borrow to make additional public investments. They also reduce the payoff from near-term debt reduction.

After considering other factors—including the role that fiscal policy can play during economic downturns when short-term interest rates are already so low that the Federal Reserve has little room to cut them—Elmendorf and Sheiner argue for measured, gradual debt reduction with a higher debt-to-GDP ratio than has historically been the case.