INTRODUCTION

The defining narrative of the United States of America is that of a nation where everyone has an opportunity to achieve a better life. Americans believe that everyone should have the opportunity to succeed through talent, creativity, intelligence, and hard work, regardless of the circumstances of their birth. Our leaders share this support for opportunity. In a speech last fall, President Obama said that Americans should make sure that “everyone in America gets a fair shot at success.” Mitt Romney has repeatedly spoken about an opportunity society, where people can “engage in hard work, and pursue the passion of their ideas and dreams. If they succeed, they merit the rewards they are able to enjoy.”

##1##

Americans have an unusually strong belief in meritocracy. In other nations, circumstances at birth, family connections, and luck are considered more important factors in economic success than they are in the U.S. This meritocratic philosophy is one reason why Americans have had relatively little objection to high levels of inequality—as long as those at the bottom have a fair chance to work their way up the ladder. Similarly, Americans are more comfortable with the idea of increasing opportunities for success than with reducing inequality. When the American public is asked questions about the importance of tackling each, a far higher proportion is in favor of doing something about ensuring that more people have a shot at climbing the economic ladder than is in favor of reducing poverty or inequality.

One way of thinking about opportunity is in terms of generational improvement in living standards. Among today’s middle-aged Americans, four in five households have higher incomes than their parents had at the same age, and three in five men have higher earnings than their fathers. The extent to which this will be true for today’s children remains to be seen. More importantly, if everyone grows richer over time, but the economic fates of Americans are bound up in their family origins, then in an important sense opportunities are still limited. If a poor child has little reason to believe she can “grow up to be whatever she wants,” it may be of little comfort to her that she will likely make more than her similarly constrained parents. A better-off security guard may still have wanted to be a lawyer.

The reality is that economic success in America is not purely meritocratic. We don’t have as much equality of opportunity as we’d like to believe, and we have less mobility than some other developed countries. Although cross-national comparisons are not always reliable, the available data suggest that the U.S. compares unfavorably to Canada, the Nordic countries, and some other advanced countries. A recent study shows the U.S. ranking 27th out of 31 developed countries in measures of equal opportunity.

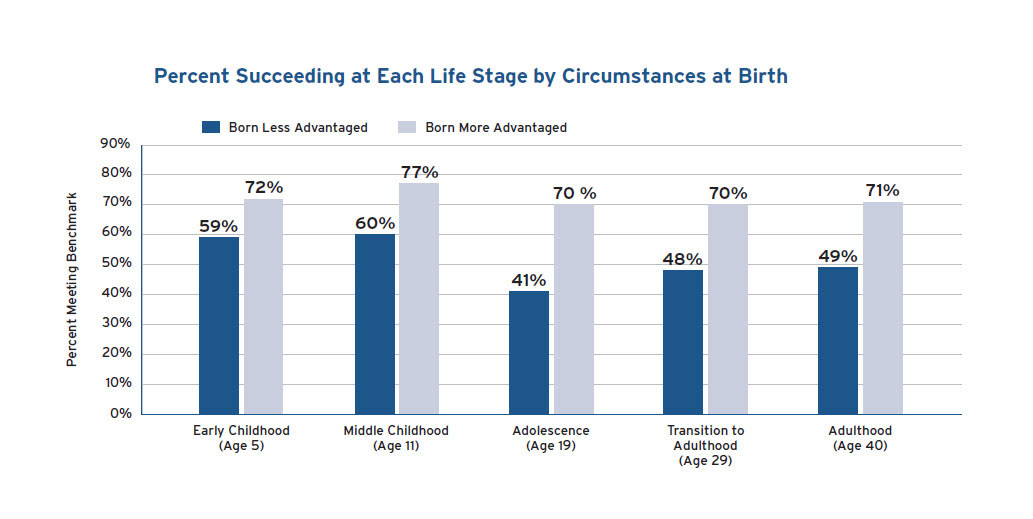

People do move up and down the ladder, both over their careers and between generations, but it helps if you have the right parents. Children born into middle-income families have a roughly equal chance of moving up or down once they become adults, but those born into rich or poor families have a high probability of remaining rich or poor as adults. The chance that a child born into a family in the top income quintile will end up in one of the top three quintiles by the time they are in their forties is 82 percent, while the chance for a child born into a family in the bottom quintile is only 30 percent. In short, a rich child in the U.S. is more than twice as likely as a poor child to end up in the middle class or above.

Why do some children do so much better than others? And what will it take to create more opportunity? The remainder of this paper addresses these two questions.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).