The recent ousting of Prime Minister Nawaz al-Sharif following a corruption scandal has increased instability in Pakistan, writes Bruce Riedel. He recommends opening dialogue with the new prime minister while keeping our distance from the country’s most powerful institution, the military. This piece was originally published by The Daily Beast.

The most dangerous country in the world just got even more unstable.

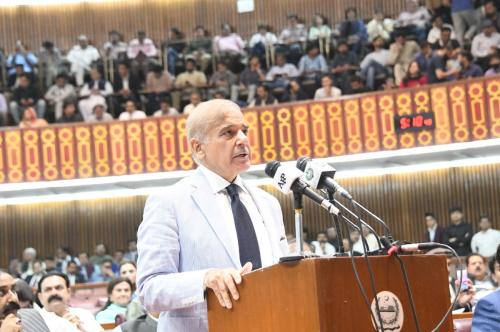

The recent demise of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif is a victory for the country’s generals who despise Sharif for being “soft” on India and seeking peace in Afghanistan. His brother Shahbaz will replace Nawaz but faces a country in turmoil and must first win a by-election to parliament to take on the job.

Make no mistake: Instability in Pakistan is dangerous for the United States and for the world. Pakistan has the fastest growing nuclear weapons program in the world, along with intermediate-range ballistic missiles, American supplied F16 jets, and is developing tactical nuclear weapons.

In Pakistan’s 70-year history, no prime minister has ever served a full term in office; all 18 attempts have left short of time. Sharif has been prime minister three times over the last three decades and has been removed from office each time. His administration this time had the distinction of being the first elected government ever to replace a previously elected government by the ballot box.

The Supreme Court ousted Sharif due to a corruption scandal that emerged more than a year ago, when the so-called Panama Papers were leaked. Investigators found that Sharif’s family had sizable amounts of money and assets in London, including four luxury flats that allegedly had been purchased with illegal proceeds. A Joint Investigation Tribunal dominated by the army concluded that the family had assets far beyond their income and recommended the case to Pakistan’s Supreme Court.

A key part of Sharif’s defense rested on the testimony of the former Qatari prime minister, Hamid bin Jassim bin Jaber al-Thani (HBJ). HBJ was a business partner of Sharif and has provided written evidence to corroborate Sharif’s claims about how he legitimately acquired the London properties. But the tribunal rejected the Qatari’s letters.

In the end the Supreme Court convicted Sharif on a technicality: He had failed to report to parliament a work permit he had obtained while in exile that facilitated travel to the United Arab Emirates. The court referred all the other charges against the prime minister and his daughter and two sons for further judicial review. So the case will drag out for months.

Nawaz reportedly wants his younger brother Shahbaz to fill out his five year term before elections next year. Shahbaz has been governor of Punjab province, the nation’s most populous, and is a competent and successful executive. The family dominates the ruling party, the Pakistan Muslim League (PML), and has a strong majority in parliament. It’s two largest rivals led by Imran Khan and Bilawal Bhutto can not block the PML’s choice. But Shahbaz must first win election to the parliament which will take a month or more. In the interim a former oil minister, Shahid Khasan Abbasi, will be the temporary prime minister.

I first met Shahbaz when he came to Washington in 1999 to warn the Clinton White House that then Chief of Army Staff General Pervez Musharraf was planning a coup to oust his brother. We listened sympathetically but couldn’t stop a coup in a nuclear weapons state. After the coup took place the brothers lived in exile in Saudi Arabia for almost a decade. The army wanted them never to return, but Musharraf was driven out of power by a popular movement.

The army is the most powerful institution in Pakistan and has a long history of removing prime ministers that its leadership dislikes. Sharif has been in the army’s crosshairs since he accepted President Bill Clinton’s call for a unilateral cease fire during the 1999 Kargil war with India. When Sharif pulled back Pakistani troops in the ceasefire, he set the stage for the coup that ousted him months later, which Shahbaz predicted. He was able to return only after the 2007 collapse of General Musharraf’s dictatorship. From exile Musharraf now has hailed the supreme court decision as “historic.”

Nawaz Sharif’s fitful attempts to improve Pakistan’s troubled relations with India since the 1990s lie at the core of the army’s dislike for him. Nawaz and Shahbaz are more interested in economic growth than pursuing Pakistan’s vendetta with India. Nawaz has also sought to persuade the Afghan Taliban to negotiate with the government in Kabul, a stance that the army opposes as well. Sharif has kept Pakistan out of the Saudi war in Yemen for over two years, producing serious strains in Pakistan’s ties to Riyadh, and more recently he has been neutral in the Qatari dispute with the kingdom.

The military is also among the most corrupt institutions in the country. Officer pensions are very generous. Musharraf lives in Dubai with an extensive portfolio. The army is the nation’s biggest property developer with large holdings in the cities, including 35 square kilometers of sea front in Karachi. Several large trusts are run by the army, with billions in assets.

In addition to the threat it poses as an unstable nuclear power, Pakistan is a patron—and victim—of terrorism.

It is home to numerous terrorist organizations, including Lashkar-e-Tayyiba, the Haqqani network, al Qaeda’s emir Ayman al-Zawahiri as well as Osama bin Laden’s son, Hamza bin Laden. It has been the target of dozens of terrorist attacks by the Pakistani Taliban. Some 55,000 Pakistanis have been casualties of terrorism in the last decade.

The border with India is tense after a series of violent incidents. The two have fought four wars. There are no direct air flights between Islamabad and New Delhi.

Pakistan is also China’s closest ally, and Sharif is responsible for negotiating an enormous $50 billion development deal with Beijing.

The Trump administration is still reviewing U.S. policy toward Pakistan. Since 2001 the U.S. has provided over $30 billion in aid to Pakistan, but the Congress has become much more reluctant to approve military assistance since Osama bin Laden was killed in a safe house just outside the Pakistani equivalent of West Point in Abbottabad in 2011.

The president avoided a bilateral meeting with Nawaz Sharif when they both were in Saudi Arabia in May, which has been interpreted in Islamabad as a signal of cooling ties.

The corruption scandal is outside of Washington’s influence, but how it plays out will have significant consequences for South Asia and beyond. Opening a high-level dialogue with the new prime minister would be a prudent step. Washington should avoid the temptation to deal directly with the generals, that is a path to failure.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edPakistan’s generals strike again: Sharif’s ouster is a scary shake-up

July 31, 2017