After months of announcements, major cash infusion, and a limited beta program, Jet—a new competitor to Amazon for e-commerce supremacy—went live to the public. Jet promises to offer customers rock-bottom prices for a bevy of personal and household goods, using a combination of owned warehouses, direct partnerships, and even a concierge shopping service.

The launch was greeted by the Wall Street Journal and other outlets with reporting on their business model and the potential to scale up for the long-haul. If successful, Jet could cause more pain for brick-and-mortar retail establishments, already competing with over $300 billion in online sales, and continue to alter careers for the 15.5 million people working in retail.

Jet’s success would also likely mean a rise in urban trucking at the expense of local retail trips.

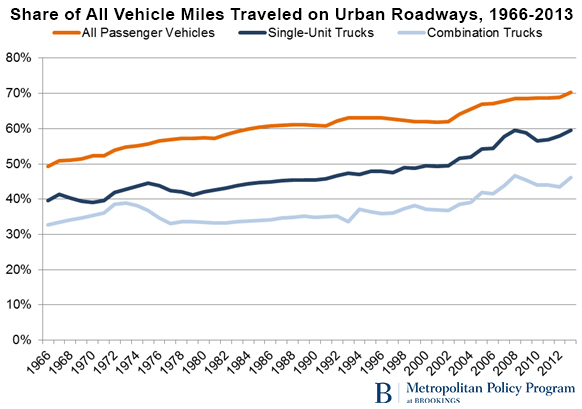

While trucking is often pigeonholed as a long haul interstate highway phenomenon, the industry is increasingly urban. Whereas passenger cars went majority-urban in miles driven back in 1967, trucks didn’t experience major urban growth until the mid-1990s. Just two decades later, single-unit trucks—two-axle vehicles with at least six tires—already drive 60 percent of their miles on urban roadways and combination trucks will reach 50 percent in the coming years.

Source: Brookings analysis of

Federal Highway Administration

data

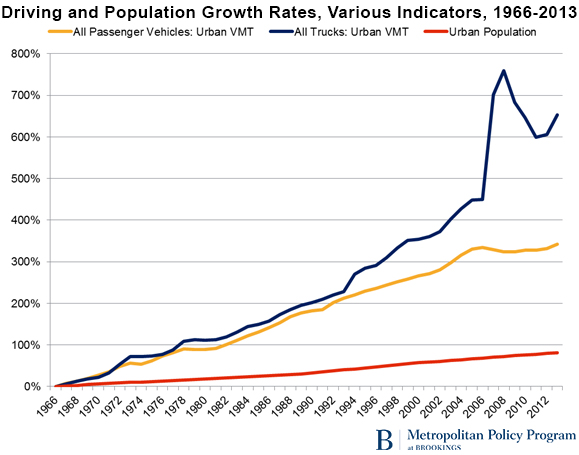

Another way to see trucking’s urban trajectory is to view aggregate growth since the 1960s. While urban vehicle miles traveled for both passenger cars and trucks grew steadily between 1966 and 1990—in both cases, far surpassing urban population growth—urban trucking absolutely exploded thereafter, reaching almost 800 percent growth until the Great Recession led to reduced demand. That pattern coincided almost perfectly with the rise of e-commerce and the use of digital communications to manage shipping for logistics firms like UPS and FedEx and major private shippers like Walmart.

Source: Brookings analysis of Federal Highway Administration and World Bank data

With new companies like Jet and continued growth in stalwarts like Amazon, we should expect e-commerce and urban trucking to keep growing. Those patterns bring some significant implications at all levels of government.

On the transportation side, freight investment will need to be targeted at pinch points and bottlenecks. Those specific sites of congestion deliver disproportionate costs to shippers, which get passed along to consumers, and create supply chain uncertainty. Cities and suburbs will also need modern parking regulations and street design, ensuring trucks can access dense pick-up and delivery locations that won’t interfere with local vehicle, bike, and pedestrian traffic. The same applies to the noise and other environmental impacts trucks deliver at a higher relative rate than smaller vehicles.

Of course, there are other land use-related effects that will emerge from a continued growth in e-commerce. Big box retailers that more directly compete with internet giants must consider new real estate models, which may include reduced store space and heightened calls for redevelopment of vacant sites. Dense urban stores could also take a hit, leading to increased demand for less fungible retail like restaurants. Finally, internet giants rely on dispersed supply chains, meaning the metropolitan fringe may see an increase in warehousing facilities like what’s taking place in Southern California.

Ideally, metropolitan areas and their state and federal peers will recognize that urban freight isn’t going away, and begin to design policies to address the new reality of the modern metropolis. In the meantime, enjoy Jet’s low-cost goods while you can get them. I’ve already got my eye on a new TV that will look great in our basement.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

New e-commerce entry Jet means rock-bottom prices … and more city trucks

July 28, 2015