In the United States, the COVID-19 pandemic struck a uniquely precarious workforce: No other high-income country has experienced such deep job losses. The shock has exposed and widened rifts in our two-tiered labor market—between workers with stable jobs and the newly unemployed, between those who can work from home and those who can’t, and between high-income workers and those struggling to make ends meet.

These challenges were not inevitable. Before the pandemic, U.S. labor markets were historically tight—what labor experts called a “now or never moment” to improve job quality and worker mobility. But low-wage workers saw only marginal gains. Today, the problems are accelerating, and the stakes are even higher. COVID-19 job losses hit low-wage workers the hardest, and these workers are having the hardest time getting back on their feet. Meanwhile, the pandemic is rapidly shifting consumer preferences and company behaviors, with demand for digital services surging. But few unemployed workers have the time or resources to reskill and find new work on their own. If these shifts continue, many low-wage workers may see less demand for their labor in the long run—meaning lower wages and decreasing job quality for those who can find work, and long-term unemployment for those who can’t.

The pandemic is an urgent reminder of what long-term labor trends have been illustrating for years: Low-wage workers need better pathways into decent jobs, and from shrinking occupations to the jobs of tomorrow. Policymakers face a dual imperative: to facilitate safe reemployment as soon as possible, even as COVID-19 continues to surge in many parts of the country, while also helping low-wage workers on the journey to jobs with dignity, stability, and a fair shot at economic mobility. While the risk of mass unemployment has already spurred large public expenditures, more funding and efforts are needed to ensure opportunity reaches those who need it the most.

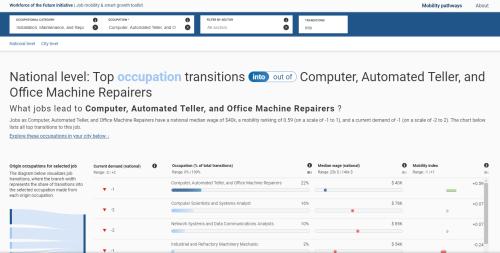

Along with state and local governments, companies and workforce organizations are on the leading edge of this work. To help, the Workforce of the Future initiative has created a new tool—Mobility Pathways—that visualizes data on thousands of real job-to-job transitions, tracing the common pathways into and out of 441 occupations across 130 industries at the national and city levels. Mobility Pathways is the first element of a multipart toolkit to support job mobility and smart growth. Its goal is to help workers (and the organizations supporting them) explore career opportunities, give companies a wider lens on recruitment and talent management, and provide tools for policymakers to target investments in talent development as a strategy to diversify and grow their economy.

How the pandemic exacerbated long-standing labor market dynamics

These problems are not new. Before the pandemic, we identified 53 million low-wage workers most of whom earned less than $18,000 per year, many stuck churning through low-wage jobs, with declining and uneven access to training, development, and career advancement opportunities. Not surprisingly, this low-wage workforce is disproportionately Black, Hispanic, and female. Using data from our Mobility Pathways tool, we can see that these workers also face lower rates of upward mobility.

Prior to COVID-19, 56 percent of occupational transitions by white men were upward, compared to only 43 percent and 37 percent for Black and Hispanic women, respectively (Figure 1). An upward transition is one likely to yield a higher wage than would be expected given the wage of the starting job.

Note: Upward transitions are occupational transitions into an occupation that typically pays more than expected, given the wage of the starting job; see technical note for a more precise definition. For each group, we estimate the share of all transitions that are upward.

Source: Brookings analysis of CPS (2003-2019) and OES (2019) data.

Recent jobs data show that low-wage workers are also having the hardest time getting back to work (Figure 2) largely because COVID-19 has disproportionately disrupted high-contact occupations (e.g., cleaning, hospitality, and food services), which tend to pay low wages.

Figure 2. The employment shock has hit low-wage workers hardest

Note: Not seasonally adjusted. We define a low-wage occupation as one that pays median wage below $17.26/h, which is two-thirds the median wage of white men. This definition builds on our definition of low-wage work in Realism about Reskilling.

Source: Brookings analysis of IPUMS CPS (2020) and OES (2019) data.

Even as it destroys jobs, the crisis is also creating a few new opportunities, particularly in digital-heavy occupations. While this may open doors for some low-wage workers, job transitions data suggest that today’s hardest-hit occupations—from waiters and bartenders to teachers and personal care aides—have not historically offered pathways into occupations that have added jobs in recent months (Figure 3). Likewise, today’s high-demand occupations like software engineering have not typically absorbed workers from the occupations currently under pressure. This mismatch suggests that many of today’s unemployed workers may find it harder than in the past to find new jobs and advance through the labor market. The accompanying technical note quantifies the economy-wide potential for growing occupations to absorb displaced workers. In 2020, that potential to absorb is at its lowest point since at least 2004.

Figure 3. Unemployed workers from the hardest-hit occupations may struggle to transition to today’s in-demand jobs

Note: The x-axis reflects the severity of COVID-19-related unemployment for each occupation, represented by percent change in the average number of workers between Q1 and Q3 2020 (with the hardest-hit occupations to the left). The y-axis reflects the historical likelihood that each occupation could transition into one of today’s resilient occupations, represented by the share of job transitions between 2003 and 2019 that went into occupations that have added jobs since January 2020. For readability, the figure shows only occupations with more than 330,000 workers, which together account for 65 percent of employment and 82 percent of employment in shrinking occupations.

Source: Brookings analysis of IPUMS CPS (2003-2020) and OES (2019) data.

That said, low-wage workers in certain struggling occupations have realistic pathways into a number of in-demand jobs. For example, cashiers and retail salespersons—which both face declining demand—have historically transitioned successfully into telemarketer and stock clerk jobs, demand for which is growing. While not offering higher wages, such transitions could put people back to work quickly with little to no training. A more promising possibility is for workers in administrative jobs (e.g. administrative assistants, office clerks, and other administrative support workers), occupations which are seeing significant displacement due to long-run trends but that have commonly transitioned successfully to jobs as business operations specialists—a higher-paying occupation that has seen some growth in recent months.

Mobility Pathways offers new insights that can help address our skewed labor market dynamics. With millions of workers seeking reemployment, it can target promising transitions into resilient occupations that offer good wages and opportunities for upward mobility, tailored to workers’ experiences and location. Companies can use it to widen their pools for talent acquisition and make career paths available to a greater number of workers. Policymakers can use talent development as a competitive asset to grow their economies, while providing opportunity to workers. By identifying the most realistic pathways into today’s most resilient occupations, Mobility Pathways offers a map and compass for navigating labor market shifts—during and after the pandemic.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

New but narrow job pathways for America’s unemployed and low-wage workers

November 16, 2020