In October 2022, when Giorgia Meloni became Italy’s prime minister, concerns arose about her democratic credentials. Since her youth, Meloni had been associated with far-right movements, initially with the Italian Social Movement (Movimento Sociale Italiano1) and eventually with the Brothers of Italy (Fratelli d’Italia), which were ambiguous about the fascist regime that had suppressed democracy between the two world wars. Only three months before winning the elections, she had advocated for a political stance that seemed not aligned with the other liberal democratic parties in Europe. In a public speech in Barcelona, she summarized her agenda vividly: “Yes to the natural family, no to the LGBT lobby, yes to sexual identity, no to gender ideology … no to Islamist violence, yes to secure borders, no to mass migration … no to big international finance … no to the bureaucrats of Brussels!”

Those words, and especially her branding of the European institutions as a barely legitimate bureaucratic clique, might have been pronounced by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, who is known as the standard bearer of “illiberal democracies,” new nationalists, and friends of autocrats such as Russian President Vladimir Putin. This affinity has fueled concerns that Meloni’s leadership of the third most populous country in the European Union would undermine efforts to achieve greater political integration within it, bring back nationalism in the heart of Europe, and increase the influence of autocratic regimes in the West. In such a case, Meloni might have become the crucial link in a chain reaction spreading autocracy worldwide.

This raised the question: would Meloni become a new autocratic leader in the heart of Europe or rather a mainstream conservative politician? To answer it, her actions have been scrutinized on three counts. Firstly, would Meloni uphold the rule of law while managing consensus within the country? Secondly, since consensus was also dependent on the state of the economy, would she tackle the Italian economy’s traditional weaknesses by adopting politically costly reforms? Finally, considering the close ties between the Italian and European economies, would Meloni pursue her nationalist goals while also forging strong alliances in Europe in order to play a leading role in a challenging global context?

Almost two years into Meloni’s term, this sequence of questions (consensus-economy-Europe) is starting to get some answers. In short, Meloni’s primary political objective has been to establish her party’s influence in Italy’s public administration and cultural sector, aiming to promote a right-wing narrative of the nation and paving the way for the continuation of her leadership in future legislatures. Meloni portrayed this endeavor as a way to stabilize Italy’s political system and, as a direct result, let the economy benefit from a stable legislative framework. Ultimately, she hoped the resulting stronger economy would restore Italy’s credibility in Europe and in the international community.

Critics from the opposition describe this sequence differently. They argue that Meloni is pushing the Italian political system toward an “autocracy-light” model and that her government has made no significant contributions to stabilizing the economy, which is being sustained primarily by European subsidies. Finally, her international strategy’s shortcomings and ambiguities are isolating Italy from the other liberal democracies and drawing it closer to autocratic regimes.

In the following sections, this paper presents an assessment of Meloni’s government following the chain described so far: building consensus within Italy, managing Italy’s economic weaknesses, and forming European alliances. In this regard, three key factors stand out. First, Meloni’s agenda of institutional reforms aims to boost the prime minister’s authority, concentrating more power (and potentially consensus) in her hands while diminishing the role of parliament. Second, the Italian economy is expected to experience reduced fiscal support from Europe, thereby returning to lower growth rates after 2025. Lastly, recent events in European politics have shown that Meloni has become isolated from Europe’s decisionmakers. This isolation may weaken her hopes of becoming a central figure in the conservative shift that has characterized global politics, particularly in the case of a conservative victory in the 2024 U.S. presidential elections.

In the coming months, Italy’s complex political framework may force Meloni to decide whether to become a European centrist stateswoman or return to her nationalist convictions. This paper suggests that Meloni should turn her sequence of priorities (consensus-economy-Europe) upside down. Starting from a new constructive European strategy, followed by economic liberalization, and finally coming to obtain domestic consensus through her concrete achievements.

1. Consensus: Concentrating power in the hands of the prime minister

Meloni became part of the Youth Front (Fronte della Gioventù) the youth organization of the far-right party Italian Social Movement (MSI), in 1992. MSI was established in 1946 by former members of the National Fascist Party and exponents of Benito Mussolini’s regime. The party later evolved into MSI-Destra Nazionale and in 1994 changed its name to the National Alliance (Alleanza Nazionale, AN). AN represented a break with the nostalgic past, positioned itself as a post-fascist party that disavowed fascism, and aimed to align with the European People’s Party, the main centrist group in Europe. However, resistance to the party’s shift toward centrism led to the collapse of AN and the foundation of Brothers of Italy (FDI) in 2012. Since 2014, Meloni has served as FDI’s president, and she has claimed continuity with the ideologies of MSI and AN, whose names and symbols, including the flame allegedly burning on Mussolini’s thumb, are still part of FDI’s emblem.

Due to the close connection between MSI’s and FDI’s personnel, the latter’s culture still clings to a distorted and nostalgic narrative of Italy’s fascist regime under dictator Mussolini (1922-1943). Hence, when Meloni was appointed, she was labeled as the first post-fascist prime minister of the Italian Republic. There were also concerns that she might become a “pre-fascist” leader by exploiting domestic problems and the threatening international context to centralize power, lock in consensus, and modify the democratic constitution approved in 1947 (when only the heirs of Mussolini’s fascist party voted against it) to gain autocratic power.

Italy’s far-right leaders had often maintained ambiguity about their agenda. Throughout its history, MSI had alternated between moderate political stances and revolutionary temptations. In a speech at the Central Committee in 1969, Giorgio Almirante, one of MSI’s cofounders and its leader until 1987, described the movement as a “non-totalitarian party, though it considers the State as diverse and superior to the party, non-nostalgic but modernist, non-nationalist but pro-European, not conservative-reactionary but socially-advanced.” At the same time, however, Almirante used to say that Italy’s right could not aim at being a normal conservative party because there was nothing to conserve in Italy. Fringes within the MSI, which saw Almirante as their reference point,2 were involved in terrorism and subversive activities. The far right’s revolutionary character was one of the reasons why the generations that grew under the MSI’s influence have been regarded as not reliably democratic.

Even after becoming prime minister, Meloni still avoided directly and unconditionally condemning fascism, unlike her predecessor, AN leader Gianfranco Fini, who labeled fascism as “the absolute evil.” However, recognizing herself in the values of the Italian Constitution, Meloni has de facto disavowed the revolutionary temptations of many of her fellows in the MSI youth organization.3 Meloni is different from some of FDI’s older members, who are still inclined to fascist nostalgia; she represents a generation of far-right leaders whose political roots can be primarily traced to the violent antagonism between far-right and far-left youth organizations after the 1970s.

For generational reasons, her political background could thus preeminently be defined as anti-left. She is now expected to complete the transformation of the revolutionary movement of her youth into a “national-conservative party.” This would require a root-and-branch elaboration of a new party program. Meloni is struggling to do this, probably because her nearly uninterrupted role in the opposition has entrenched a culture of counter-positioning rather than pro-positioning. For the time being, the foundation of a new conservative political proposal—that would likely take Meloni’s party closer to the European People’s Party—is not progressing.

Meloni’s ambiguity, however, should not be seen as a sign of a possible return to the neo-fascist revolutionary path. Fascism is a historical phenomenon characterized by the use of violence to conquer and maintain power at the expense of democratic institutions. But most modern far-right parties claim to reject the use of violence and likening them to their fascist predecessors can be misleading. More importantly, nearly 102 years after Mussolini’s “March on Rome,” the conditions of Italian society are very different from those that existed before fascism. Political violence is at historical lows. Most citizens are unwilling to relinquish the individual freedoms that have contributed to their well-being since World War II. They want to be free to wander and work around the world, without being constrained by oppressive nationalism. Poorly educated or discredited politicians chanting the greatness of an Italian atavist heritage generally sound risible. And although poverty has increased in the last two decades, most households’ accumulated wealth (Figure 1)—even in the last two decades when growth was stagnant—empowers citizens to shape their destinies and those of their children, irrespective of the governing authority. That said, Italy’s private wealth is partly a matter of “monetary illusion” (in other words, mistaking nominal value for previous purchasing power) because its real value is no longer increasing. Moreover, over the last 15 years, the wealth of Italian households has significantly declined in comparison to other larger European economies. In 2011, the average wealth of Italian families was 75% higher than that of German families, but 12 years later, it was lower. Factors such as low income growth, a steady increase in public debt, and the relative decline of wealth keep undermining citizens’ trust in public life.

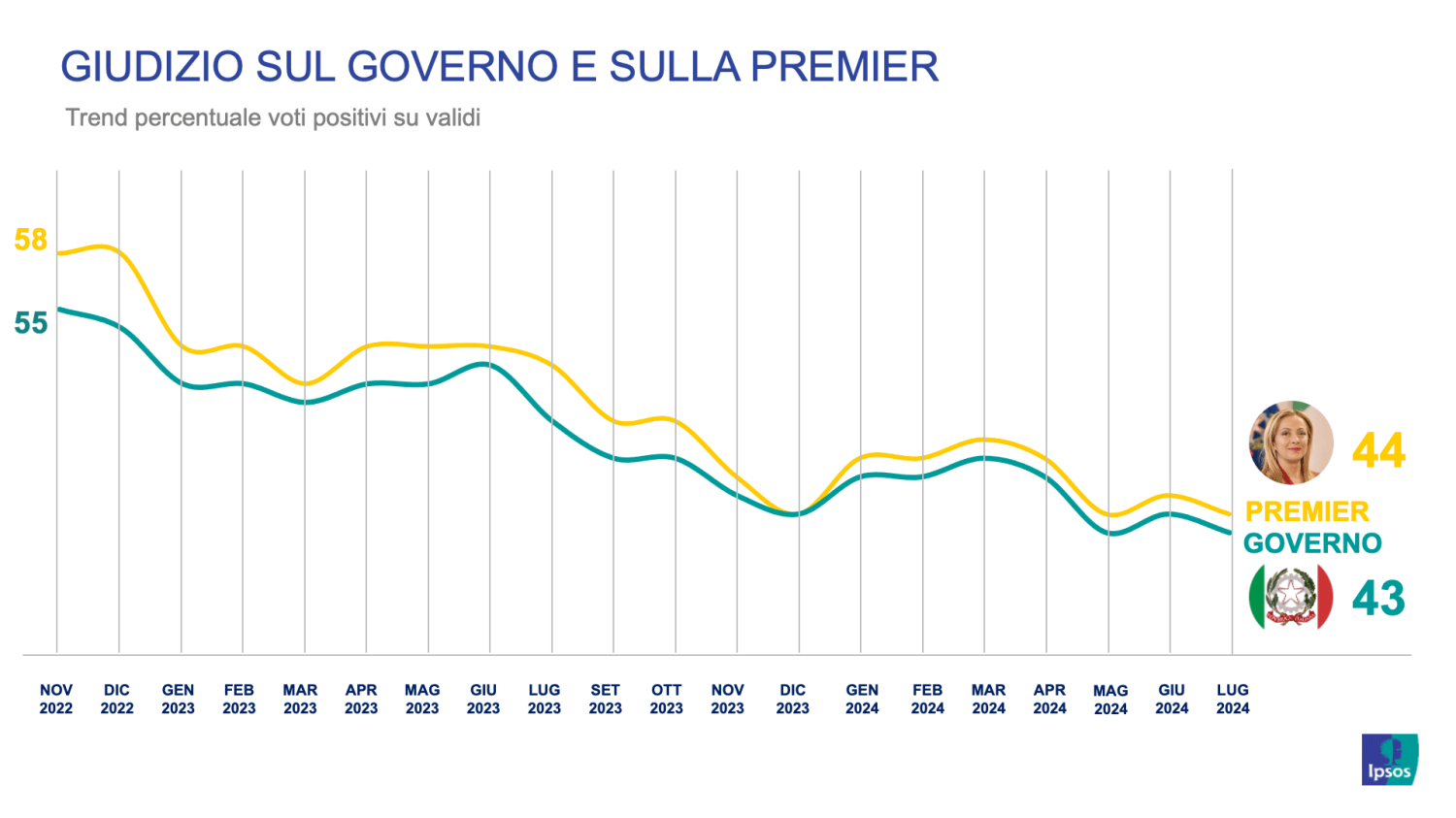

In a society defined by wobbly trust levels, consensus is manufactured through emotional appeals that are fueled by victimhood, revanchism, hostility toward strangers, and ideological solidarity with “indigenous” people. Meloni’s emotional and direct personality has become central to this narrative. Her rhetorical and facial expressivity, at the same time ironic and consoling, make her an archetypal theatrical figure—the shrewd commoner in an Armani suit—that her country fellows seem to appreciate in the context of Italy’s 24/7 political comedy. According to the data collected by Ipsos and published by Corriere della Sera, an Italian newspaper (Fig 2), Meloni’s level of support among the citizens has been declining from 58% to about 44% but remains comparatively solid.

Meloni’s level of support among Italians

Source: Data collected by Ipsos, published by Corriere della Sera.

Controlling the all-important public television networks, the government parties (a populist-conservative coalition of three parties: Meloni’s Brothers of Italy, Matteo Salvini’s Lega, and Forza Italia, founded by former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi) are shaping Italy’s public discourse around the leader’s figure. Opinion makers use a daily bulletin issued early in the morning by the prime minister’s office to discredit the government’s opponents, foreign leaders, or independent intellectuals. The government has a limited need to strongly coerce Italian media, as large swathes of the chattering class have often been inclined to align behind strong powers. Private media outlets are mainly owned by industrialists who are keen to please the government or face intimidation if they do not.4 The government has also changed the top managers of Italy’s museums and cultural institutions, and is trying to do the same in universities, in order “to free culture from decades of left wing hegemony,” as described by a Brothers of Italy minister of parliament. Much of this has been lost on foreign media, which has been generally attracted by the colorful and approachable side of Meloni’s personality, as is depicted in Italy’s public communications.

Although the rule of law in Italy is in a better state than in Hungary, the direction of travel may be the same. The low level of independence of Italy’s judiciary system (a feature that actually goes back to the Kingdom of Italy) was highlighted in the European Commission’s 2023 Rule of Law Report. The commission then observed in its 2024 update that: “The Government has submitted to Parliament a draft constitutional reform concerning the separation of careers of judges and prosecutors and the establishment of a High Disciplinary Court in charge of disciplinary proceedings against ordinary magistrates.” Reforming the judiciary has been a pet project of Italy’s right-wing parties ever since Berlusconi was relentlessly pursued by a succession of public attorneys, and many political forces have tried to interfere with Italy’s judicial system since 1947. Meloni’s new reform project is now under scrutiny by the European Commission because it would allow even more government interference in the judiciary—but it is also true that she is exploiting existing flaws in Italy’s democracy and the shallow roots of its liberal principles.

In the context of public mistrust, the suppression of checks and balances, and the prevalence of one narrative, are often misinterpreted as a way to make governing more efficient. Over time, particularly if people feel that the economy is not improving, this combination of “political power, democratic mistrust, and economic decline” can give impulse to an autocratic drift.

In the name of defending the Italian people’s cultural homogeneity and traditional roots, Meloni aggressively opposes what she depicts as “non-Italian” values—especially where the leader of the opposition, Elly Schlein, is concerned. Schlein has three passports, a foreign surname, and is bisexual. Both Meloni and Schlein appear uninterested in how economies work and have little experience in global politics. Their clash is one between tradition and modernity, polarizing Italian politics around their two figures. The ensuing tension is instrumental for Meloni’s most important constitutional reform project: the “premierato,” or the direct election of the premier by the Italian people. Or, in her words: “the mother of all reforms.”

Italy’s 1947 constitution created a parliamentary democracy with a strong legislature, a comparatively weak executive, and most importantly, an indirectly elected president who can invite whomever he or she perceives is the leader of the strongest party to form the government (the president can also veto ministerial appointments and return draft laws to parliament for reconsideration). In times of crisis or deadlock, Italian presidents have regularly intervened to hand the leadership to “technocratic” governments. The Constitutional Commission opted for a stronger parliament and a relatively weaker executive specifically to prevent a concentration of powers in the hands of the prime minister, similar to the one that characterized the fascist regime. As a result, the Italian Republic has had 68 governments since its proclamation, most lasting just over a year.

Meloni’s reform, which was approved on June 18, 2024, by the Senate, the parliament’s upper chamber, would concentrate powers in the hands of a prime minister strengthened by a direct popular mandate, reduce parliament’s balancing powers, and sideline the pivotal role of the republic’s president. This sharply increased authority would make it easier for the prime minister to shape policy, consolidate power, and increase his or her chance of reelection for a second five-year term. Because the prime minister would still need a parliamentary majority to govern, Meloni is also proposing that whichever party alliance wins national elections should automatically receive 55% of the seats in the legislature.

Meloni argues that this centralizing constitutional redesign is a necessary remedy to Italy’s long-standing political instability. In its cited country report on the “Rule of Law,” the European Commission observes that in case of an anticipated end of a government, “With this reform, it would no longer be possible for the President of the Republic to find an alternative majority and/or to appoint a person outside Parliament as Prime Minister. Some stakeholders expressed concerns at the proposed changes to the current system of institutional checks-and-balances, as well as doubts as to whether it would bring more stability.” Critics such as constitutional law scholar Gustavo Zagrebelsky charge that Meloni’s real goals are in line with the far right’s preference for illiberal democracy, in which democracy is limited to the expression of popular will in elections. In terms of political theory, one could add that political formations like Meloni’s Brothers of Italy believe in “majoritarian radicalism,” in which checks and balances—such as constitutional courts, the judiciary, independent agencies—should be limited once the people have expressed themselves in favor of the executive leader.

Meloni’s project to centralize power in the prime minister’s office can also be seen as a reaction to how globalization and European countries’ increased interdependence reduced Italy’s political options.

In a carefully crafted statement about the role of the nation-state, Meloni associated the idea of the fatherland with the uniqueness of Italy’s values and historical heritage: “I have always thought that both the Nation and the Fatherland were natural societies, that is, something that is naturally in the hearts of men and peoples and is independent of any convention. Just as the family is a natural society.” The coincidence of a people and a nation-state, and their uniqueness, presuppose that they are different from others and that they should “come first” in the government’s agenda. In the end, this nationalism means opposing the European Union, which was founded to overcome ancient enmities rooted in toxic nationalism, and today serves above all to help Europeans collectively regain control over globalization. Not incidentally, Meloni supports forming alliances with other far-right governments or political movements that oppose the EU, often leading to her becoming isolated in Europe’s decisionmaking.

Meloni’s government is the first in decades to enjoy a comfortable majority. But changing Italy’s constitution requires either a two-thirds majority in both houses of parliament or a majority in a popular referendum. The opposition parties have rallied against the premierato. Schlein, leader of the center-left Democratic Party, called the premierato a “dangerous” decision that reflects the Italian right’s penchant for strongmen (or in this case, strongwomen). Without the majority required to approve the reform in the parliament, it is likely that there will be a referendum. In that case, Meloni will turn the popular consultation into a vote of confidence from the Italian people. In the event that Meloni wins the referendum, she would become the prime minister with the most powers in the republic’s history and could exercise those powers without hesitation also thanks to the political mandate received from the popular consultation. The referendum’s outcome, however, is likely to also depend on the economic situation. Voters’ evaluation of the government’s impact on the economy will thus be crucial.

2. Italy’s non-Italian economic miracle

Meloni has been arguing that Italy is outperforming many other European countries, such as Germany and France, and that this success is due to her government’s ability to provide medium- and long-term economic stability. Since before the COVID-19 pandemic, Italy’s economy has indeed shown signs of vibrancy. By the end of the first quarter of 2024, Italy’s gross domestic product (GDP) had increased by 4.2% compared to before the pandemic recession began in March 2020. In comparison, the euro area average was 3.5%, with France at a much lower level and Germany’s GDP even declining. Italy’s positive performance is largely attributed to the significant fiscal policy measures implemented at both the EU/eurozone and national levels to counteract the economic shocks of recent years. Italy has benefited more than most other eurozone countries from those temporary fiscal supports.

During the pandemic, Italy received an astounding amount of financial resources from the EU in grants and transfers. Moreover, during the same period, Italy introduced an overgenerous subsidy scheme to promote the energy-efficient renovation of residential buildings. Coupled with other bonuses, the total fiscal support to Italy exceeded 10% of its GDP in March 2024. Nonetheless, Italy’s cumulated growth over the past four years has been only 0.7% higher than the euro-area average (0.17% per year), falling short of justifying the notion of a new Italian economic miracle.

Figure 3 illustrates that without the impact of EU funds on its GDP, Italy’s economic growth would have been significantly lower compared to France and Germany.5 Once corrected for the EU funds’ estimated impact, Italy’s GDP would have remained stagnant between 2023 and 2024, and its debt-to-GDP ratio would have continued to rise.

Italy’s manufacturing sector is still vibrant. Its performance has been strong over the last two decades even compared with Germany’s. However, the service sector is dragging down Italy’s economic growth. While, in aggregate, there has been a slight increase in productivity, it has not been sufficient to offset Italy’s deteriorating fiscal conditions. Italian Finance Minister Giancarlo Giorgetti reasonably called on his fellow politicians to cease living under the effects of “LSD” (Laxity-Subsidies-Debt) and to get their act together in preparation for difficult times ahead.

The moment of truth is approaching as a new set of European fiscal regulations, which had been suspended following the COVID-19 pandemic and recession in 2020), will affect the upcoming EU budget legislation in September 2024. Each EU member state must commit to putting its public finances on a sound footing or face sanctions and exclusion from the European Central Bank’s umbrella protecting the euro area.

The benefits of the European funds will be especially felt between 2023-2025. Italy’s economic growth could thus be higher than 1% in 2024 and 2025, exceeding the eurozone average, with strong benefits for the country’s public accounts. Buoyant tax revenues are already reducing the risk of a fiscal correction and granting breathing space to the government.

In fact, the end of 2024 and 2025 may provide more positive economic surprises. This period thus represents the most favorable window of opportunity to reform the Italian economy. However, the government is not working on modernizing the economy. Unlike other right-wing governments, Italy has no significant program in store for market liberalization, tax cuts, or red-tape reduction beyond what is required by the European Commission. Meloni does not seem to consider this a priority, focused as she is on keeping public support for her government as strong as possible.

However, things might change after 2025 when maintaining fiscal discipline will require either lower expenditures or higher taxes, which could force Meloni to break some key electoral promises.

Faced with economic constraints, populist politicians have a penchant for blaming Europe. But that may not work this time: the new EU fiscal rules are designed to prevent national governments from accusing Europe of imposing unwanted measures. Under the new reform, the fiscal strategies to decrease the national debts over four or seven years are developed together by the European Commission and the relevant national government, leaving no room to scapegoat Brussels. The preliminary agreement with the European Commission increases the national government’s responsibility for the prescribed reforms and fiscal measures.

3. Meloni’s unraveling European plans

The June 6-9 European elections were central to Meloni’s plan to obtain more fiscal leeway from the European Commission because polls were showing that the Italian prime minister could obtain significant success, especially compared to her French and German colleagues. Meloni was calculating that her improved stature would give her leverage to negotiate for leniency with the new European Commission. She even postponed updating Italy’s budget plan (required by EU and national regulations) from April to September to gain a better understanding of how the elections would change Europe’s political dynamics. On June 10, Meloni emerged as a clear winner in the European vote, while French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz suffered defeats. Nonetheless, subsequent events did not unfold as she hoped.

While Meloni was heralded at home and by the international press as a new leader of Europe, she was sidelined by her peers both during the G7 summit she hosted in Apulia and in Brussels during negotiations to decide the future heads of the European institutions. Despite media acclaim for the G7’s apparent success in Apulia, the meeting turned out to be a personal setback for Meloni: Macron criticized her for deleting or downplaying references to abortion and LGBTQ+ rights in the final communiqué and singled out Meloni as a leader not aligned with the other liberal democrats. According to an article by The New York Times, “When told of Ms. Meloni’s position, American officials say, President Biden pushed back, wanting an explicit reference to reproductive rights and at least a reaffirmation of support for abortion rights from last year’s communiqué. Several other G7 members agreed with Mr. Biden.”

First in Apulia and later in Brussels, Macron and Scholz, along with the heads of the main pro-European party groups in the European Parliament (the European People’s Party, the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats, and Renew Europe), exploited the incident to sideline Meloni during discussions about renovating EU institutions. A surprised and outraged Meloni threatened to retaliate after the French elections on July 7. In the French National Assembly vote, Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally was expected to win the most seats, possibly resulting in a considerable loss of credibility for Macron.

However, the possibility of Le Pen’s party winning in France unsettled financial investors, driving up the cost of refinancing Italian debt—a metric (“lo spread”) long treated as a bellwether of Italy’s financial and political stability. Long-term interest rates increased in France, but also significantly in Italy. Even the euro exchange rate weakened, reflecting growing uncertainty about the future of European integration with the rise of nationalist forces.

What happened between the two rounds of the French elections showed that for the sake of Italy’s economic health, Meloni should have hoped that her fellow EU leaders would reinforce the process of European integration. She should have pursued a constructive dialogue with the pro-European leaders, including Macron and Scholz. A more stable European framework could strengthen Italy’s economic and political stability. On the contrary, in a financially challenged environment, even self-governance and individual liberties can suffer. Looking forward to an anti-European French prime minister or U.S. president is a clear indication that Meloni did not appear to have grasped how Italy’s economic and political stability depend on its active cooperation within the EU and international alliances. In this regard, she still acted more as an ideologue than a stateswoman.

This contradiction needs to be analyzed. Meloni frequently asserts that other European leaders should defer to her because she is the leader of “a great nation,” or because she heads “the most stable government in Europe.” The argument that Italy, as one of the largest countries in the EU, should receive special consideration in appointments or common decisions is based on a view that EU membership positions should be assigned according to the size of each country’s financial or operational contributions, regardless of its political inclination or regime.6 However, the European Union is not just an international organization; it is a supranational institution whose member states and citizens share a common set of legally binding norms and a decisionmaking process that does not require unanimity. States and their citizens will sometimes be in a minority, and others’ positions—the majority—will prevail. For this supranational democratic principle to work, it has to be shared and respected everywhere across the European space, on the understanding that the sacrifices and benefits will over time be reciprocal.

By emphasizing the primacy of national interests over European majorities, Meloni (and her advisers, who are rooted in nationalist ideology) undermine or even actively work against a foundational principle of the European Union. With nearly one-third of the members of the European Parliament now representing euro-skeptic positions, the risk to Europe’s political coherence and ability to act is very real. Consequently, pro-European leaders tend to sideline Meloni, like other euro-skeptic leaders, in their collaborative decisionmaking process.

Meloni’s sovereignism is not about leaving the EU (especially after Brexit’s failure), but about rebuilding the Europe of nations—transforming the supranational institution into an organization between states and resisting any further integration or broader application of majority voting. This is the reason why conservative euro-skeptics or outright nationalists cannot easily be included in decisionmaking processes about putting together the next European Commission or setting EU policy.

Meloni’s strategy backfires

Since becoming prime minister, Meloni was expected to complete a transition from the leader of a far-right party to that of a traditional conservative one. Her idea was to remain in an intermediate position as a pivot between the European establishment and the surging nationalist parties. Meloni played a critical role as president of the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) parliamentary group, a political formation that maintains that “The European Union has overreached … [and] become too centralized, too ambitious, and too out of touch with ordinary citizens.” It envisions “a reformed European Union as a community of nations cooperating in shared confederal institutions in areas where they have some common interests that can best be advanced by working together.”

There was no ambiguity about the fact that Meloni had been chosen to lead an anti-European alliance. Meloni’s main ally in the ECR group is Poland’s Law and Justice Party, which governed Poland from 2015 until December 2023 before being ousted by a pro-European coalition. (Britain’s Conservatives were part of the group for the decade before Brexit.) During its time in power, Law and Justice changed the Polish Supreme Court’s role and composition, eliminated constitutional checks, reduced the independence of public administration, restricted independent media, and curtailed freedom of speech and assembly. As a result, in 2017, the European Union initiated legal proceedings against Poland (as well as Hungary) for violating its fundamental principles. The procedure was then closed in 2024 when a new government was elected.

The new Polish coalition government is held together by its pro-European stance and opposition to Law and Justice. Prime Minister Donald Tusk served in Brussels as president of the European Council from 2014 to 2019 and also served as president of the European People’s Party (EPP) from 2019 to 2022. Tusk is now the leader of the largest European country whose government is led by a member of the center-right EPP, the largest political force in the European Parliament, making him an important voice both in the council and the parliament. Through the ECR, Meloni found herself opposing the EPP, indispensable to her strategy of becoming the bridge between the center and the right in Europe. The ECR aimed to become the third-largest political group in the European Parliament and to offer an alternative to the EPP, replacing the traditional left-leaning allies.

After the French elections, many far-right parties joined under a new formation, “Patriots for Europe,” which is larger than the ECR.7 Meloni’s strategy to become an indispensable interlocutor for a political shift to the right was frustrated as ECR came out of the elections as only the fourth-largest group in the European Parliament, just a whisker ahead of centrist-liberal Renew Europe.

Meloni also failed because she misunderstood two facts: first, for reasons that were explained earlier, pro-European formations, however politically heterogeneous they may be, tend to coalesce in “constitutional alliances” because they view their antagonists as anti-European and a threat to democracy; second, due to their very nature, nationalists intrinsically struggle to form alliances across nations.

Meloni’s waning influence became apparent when the pro-European leaders convened, informally in Apulia and then formally in Brussels, to select candidates for top positions within the EU. Von der Leyen was chosen for a new mandate as president of the European Commission, former Portuguese Prime Minister António Costa as president of the European Council, and Estonian leader Kaja Kallas as head of the EU’s foreign policy service. Meloni was not consulted, and she responded angrily. During the European Council vote, Meloni voted against Costa and Kallas and abstained from voting for von der Leyen, while everyone else, except for Hungary’s Orbán, endorsed her nomination. This marked the first instance of an Italian prime minister not voting for the proposed European Commission presidential candidate. When the European Parliament confirmed the appointments, Meloni’s party, alongside Hungary’s Fidesz and France’s National Rally, voted against von der Leyen. Once more, Meloni’s anger stemmed from her ideological opposition to pro-European politicians, but her actions ultimately isolated Italy from Europe’s other decisionmakers.

Conclusion

Meloni capitalized on the resurgence of nationalist sentiments in Italy and Europe by turning a small party into Italy’s primary political force and a leading conservative anti-European party in the EU. She later surprised international observers by adopting a more moderate posture, though without clearly breaking with her past or becoming a mainstream conservative leader. Yet her lack of international legitimacy and the pressing constraints on Italian public finance pushed her in that direction; she was compelled to adapt to similar rules and behaviors as other European governments and further align with American or trans-Atlantic policies. It is possible that she embraced an enthusiastic pro-American stance also as a way to distance herself from European politics and priorities.

Domestically, during her first 20 months in office, Meloni has not once presented new ideas for social change or economic renewal. After a brilliant presentation of her government’s program in October 2022, her rhetorical toolbox has often returned to the same topics as when she was an opposition leader. As mentioned, Meloni’s political experience in Italy has always been rooted more in her opposition to the left, rather than in specific cultural contents or social and economic models. In this sense, Meloni’s personal political history is also central to her problems in Europe, where her options are limited because she cannot even consider allying with the social democrats in a large European coalition. To gain power in Europe, she would need to persuade the centrist EPP to no longer be centrists—that is, to form a right-wing alliance in a bipolar political structure, which, by definition, excludes the existence of a center. But moving the EPP from its traditional centrist positioning is a long shot. It could become even more difficult after September 2025 if the center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU), currently leading in the polls, wins Germany’s federal elections and forms an alignment of CDU centrist leaders in Brussels (von der Leyen) and Berlin (CDU leader Friedrich Merz or an alternative chancellor candidate).

As a talented politician, in recent years, Meloni has felt the wind of consensus for sovereignism blowing behind her, and she has translated it dialectically into the wind of history, or a call from the people.

After Meloni was excluded from the negotiations to select European institutions’ next leaders, her party colleagues hope that the spirit of the times can again become irresistible if the United States also chooses a sovereignist and anti-European president. Asked to describe his preferred outcome for the U.S. presidential election, Nicola Procaccini, who co-leads Meloni’s faction in the European Parliament, said: “We hope that Trump will win.”

Even if a Republican president wins the U.S. election in November, however, Meloni is currently isolated in the EU and unable to leverage her political affinity with former President Donald Trump. On the contrary, she might be confronted with a slew of ambiguities, including her whole-heartedly rhetorical endorsement of militarily defending Ukraine, which was primarily grounded in her need for trans-Atlantic legitimacy. If Trump wins the U.S. presidency, Meloni might be tempted to “coherently” change course in order to align with a United States that is less supportive of Kyiv.

However, siding with Trump may cause other problems. Italy’s economy is Europe’s second industrial exporting power after Germany, and U.S. protectionism might hurt it more than other countries. Even at the domestic level, Europe’s confrontation with a new U.S. administration may wrong-foot Meloni’s government coalition, which must keep together the Lega, whose leader, Matteo Salvini, is a staunch Trump supporter, and Forza Italia, which is part of the same European party as European Commission President von der Leyen.

Meloni’s plans to become the centerpiece of Atlantic conservatism have not worked out so far. She has made several mistakes and risks making more if Italy’s economic situation worsens.

Up to this point, Meloni has prioritized managing consensus over governing the economy and building alliances in Europe. She may need to reconsider her priorities and exactly reverse them: starting with a more constructive European stance, following up with a pro-market approach to economic reforms, and eventually reaping political support. Much depends on the tough choice she is faced with: whether to become Giorgia Mercher—an Italian combination of pro-European Angela Merkel and liberal-conservative Margaret Thatcher—or to slide back to her nationalist convictions.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The author would like to thank Constanze Steltzenmüller, Ted Reinert, and Adam Lammon for their advice and assistance on this piece.

-

Footnotes

- A party founded in 1946 by former members of the National Fascist Party, such as its leader Giorgio Almirante, and exponents of Benito Mussolini’s regime. The party became later the MSI-Destra Nazionale and declared itself post-fascist. Meloni joined its youth organization, Fronte della Gioventù in 1992.

- “Almirante, despite having aligned himself with the positions of the majority of the VIII Congress, represents, in the eyes of the militants, the irreducible and anti-systemic soul of the Movimento Sociale and, furthermore, constitutes the privileged point of reference for the dissident fringes external to the party.” See Piero Ignazi, Il polo escluso. Profilo del Movimento Sociale Italiano (Bologna: il Mulino, 1989), 135.

- FDI’s ambiguous adherence to the anti-fascist values of the Italian Constitution has not entirely been cleared. On April 21, 2024, Senate President Ignazio La Russa, who cofounded Brothers of Italy with Meloni, stated in an interview with newspaper la Repubblica that “there is no reference to anti-fascism in the Constitution.” The only explicit reference to fascism in the constitution is found in the transitional and final provisions, the rules that were supposed to guide the transition from monarchy to republic. “The reorganization, in any form, of the dissolved fascist party is prohibited,” states the twelfth final provision.

- The government’s significant economic role has led even mainstream media to be complacent. Before winning the elections, Meloni benefitted from Berlusconi’s TV networks radiating her propaganda. After becoming prime minister, she could place loyalists at the helm of the national broadcasting network Rai. Both media networks, however, are less aggressive than a new media pole owned by Antonio Angelucci, a senator who owns a network of hospitals tightly connected with politicians in the public health system. Angelucci nominated Meloni’s biographer and her spokesman as the editors of two newspapers he owns.

- The National Recovery and Resilience Plan funds’ impact on the French and German GDPs is negligible and as such not considered in the graph.

- The member state’s size, geographical location, and policy track record are normally taken into consideration, for instance, when competences need to be distributed within the European Commission. In this regard, the next EU commissioner that Italy nominates is likely to have a significant role within the new EU executive body.

- On June 30, “Patriots for Europe” was presented by far-right sovereignist parties, forming the third-largest group in the European Parliament. The new party had among its members many of the parties that had joined Identity and Democracy parliamentary group but also included Hungary’s leading party, Fidesz. Even Meloni’s historical Spanish ally, Santiago Abascal, the leader of Vox, turned away from the ECR and joined the “Patriots.” Italy’s Lega also joined the “Patriots,” opening a front of domestic political competition on Meloni’s right side.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).