The volume of failed large-scale information technology (IT) projects in the public sector is troubling. These projects are failing at an alarming rate. The long history of public sector IT failures has seen billions of dollars lost, embarrassment, redundancy, waste, and a loss in public trust. In 2004, the U.S. Air Force (USAF) began work on the Expeditionary Combat Support System, a project designed to streamline and automate the USAF’s operations by consolidating over 200 legacy systems. The USAF contracted with Oracle and then Computer Sciences Corporation and by 2012, the project had spent $1.1 billion taxpayer dollars and was ultimately terminated. U.S. Senators Carl Levin and John McCain stated that this project was “one of the most egregious examples of mismanagement in recent memory.” The National Programme for IT in Great Britain has failed miserably after £12.7 billion was spent to create an online portal that would allow citizens access to their personal health information; the project will arrive four years late in 2015. In Victoria, Australia, a smartcard ticketing system for public transportation was started in 2005 and was flawed from conception. Eventually, the project was implemented years late, marred by various missteps, and went $500 million over budget.

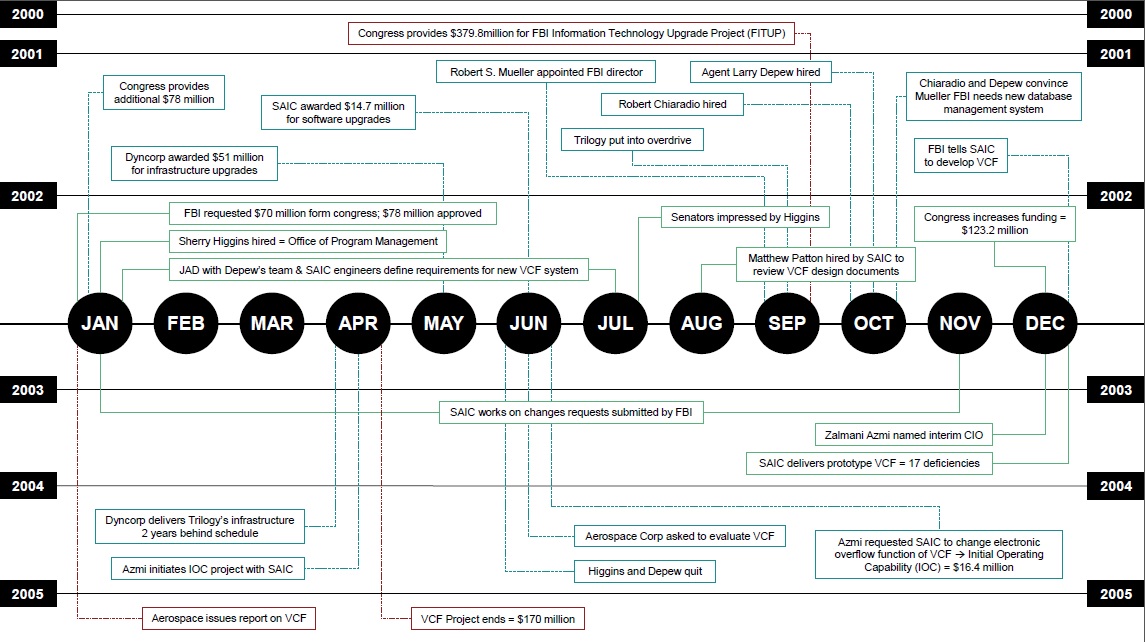

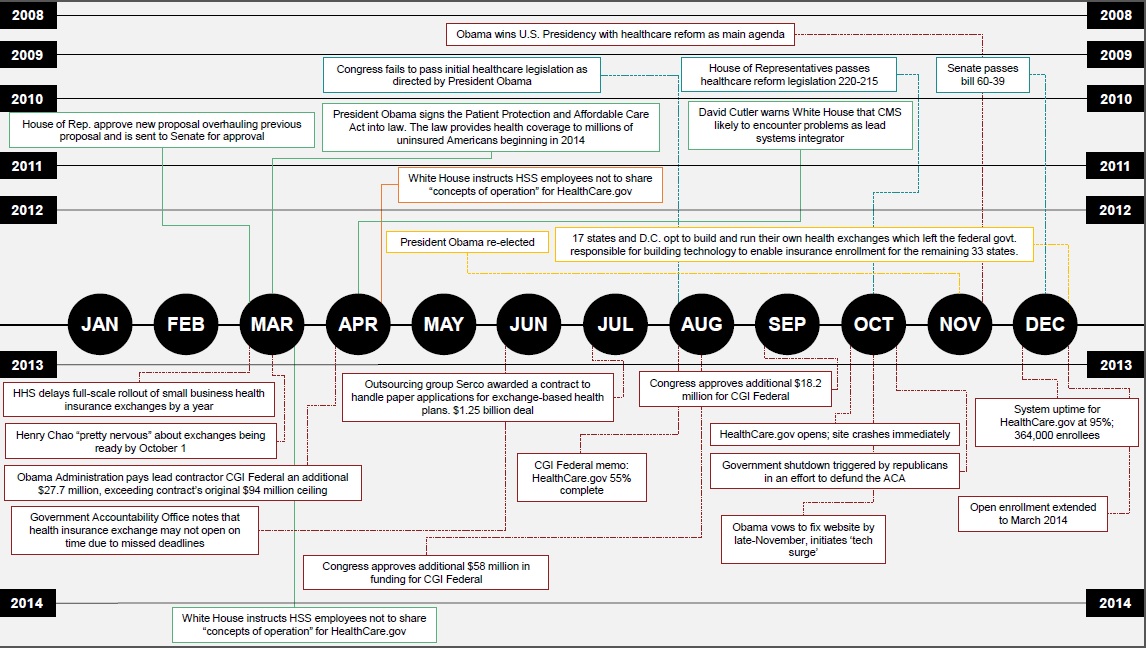

Even though leaders are familiar with past failures, many in the public sector have failed to learn from these mistakes. Bent Flyvberg and his colleagues dubbed this phenomena the “megafailures paradox” where there is continued investment in IT projects while failing to understand the causes of failures. To better understand this paradox we engaged in a study of two distinctly different large-scale IT projects: the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Virtual Case File (VCF) and the launch of HealthCare.gov. The VCF was initiated in 2000 shortly before the September 11th terrorist attacks to modernize FBI systems to simplify information flows for law enforcement and intelligence activities. After September 11th, the project received bipartisan support. HealthCare.gov is a portal that directs Americans to online insurance marketplaces.

Virtual Case File Timeline

We choose these two projects because they both provided illuminating lessons about government IT projects and differed in project scale, relevant stakeholders, and the level of public scrutiny. The FBI conducted the VCF project by themselves and with two main contractors whereas the work done on HealthCare.gov was undertaken by two agencies with over 55 contractors and sub-contractors. Also, the FBI had five years to develop the VCF where HealthCare.gov only had a brief three year period with well-publicized deadlines. Additionally, the projects were operated with different stakeholders in the national security and health care sectors. Politically, the projects received different levels of support. The VCF was popular in the wake of the September 11th attacks. The ACA faced heavy opposition throughout its development.

Both projects experienced management issues that were distinct from the IT challenges. For the VCF, the FBI continually allowed contractors to push back deadlines. The FBI held the project back due to internal quibbles and not making informed decisions. The HealthCare.gov team had to deal with political pressure and dozens of contractors to manage. Internal squabbles within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) led to chaos within the project.

Healthcare.gov Timeline

Flawed and dysfunctional dynamics within these organizations also impacted these projects. Reports about both projects noted internal behaviors of avoidance and normalization of bad behavior amongst staff members. Avoidance and normalization of bad behavior happen when employees are forced to live in and react to constraints for which they have no control over. For instance, the most resounding constraint that team members on HealthCare.gov experienced was the October 1st deadline. Although most knew the project was failing, no one could change the President’s mandate that the site would be rolled out on that date. Thus, internal processes of avoiding the real problems and normalizing behavior inconsistent with project success were enacted.

Neither project was technically challenging from a development point of view. The VCF was a database and HealthCare.gov is a web platform, which are relatively simple to develop. In the end, both projects ended up demanding more resources before they became usable. HealthCare.gov famously required President Obama’s Trauma Team to salvage it. The FBI decided to scrap the $170 million VCF and started from scratch on the Sentinel project for a price of $305 million.

Taken together, the failures of these projects provide valuable lessons for the public sector. The following 5 lessons and insights were extracted from our examination of these projects in hopes of providing more information to begin to break through the megafailures paradox:

1. Setting the appropriate tone for project development

The conditions under which projects are established set the tone for the project as a whole. Both projects studied here were initiated hastily. The VCF was supported by Congressional leaders. HealthCare.gov was met with opposition at every step. This made project managers proceed in a tentative fashion.

As evidenced by the speed in which The PATRIOT Act was introduced and passed, there was a strong need to increase safety and intelligence. The Act made several changes to U.S. law that, essentially, aimed at providing the government more teeth in their fight against crime, with a focus on terrorism. The FBI benefited from the sudden focus on anti-terrorism. They accelerated their work on the VCF and additional funds were allocated by Congress. The support was good news for the FBI but it also had an unintended consequence: it opened the project up to significant cost overruns, delays, and mismanagement due to excessive funds.

2. Expertise is critical

In both cases, individuals without formal training were making decisions about the development of the project. For instance, the HealthCare.gov project had managers that were experts in health care but lacked technical expertise. It was only possible to complete the project after a surge of technical expertise. The FBI placed one leader in charge of the project that had no formal training in IT. A contributing factor was frequent changes in leadership. During the five years the project was in development, the FBI had significant turnover in key leadership positions.

3. Politics can doom IT projects

Congress significantly underfunded the ACA because of political opposition. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that it would cost between $5 and $10 billion to implement the law. HHS received only $1 billion for general implementation work causing HHS Secretary Sebelius to piece together the funding. Conversely, Congress supported the VCF and granted the project $580 million in total over a five year period. Even though the project took longer than expected, Congress still supported the project. Politics play out in strange ways when it comes to large-scale IT projects. On the one hand, you have projects that received unwavering support, and on the other hand, you have highly contested projects. In either case, the politics focus on “ideologies” rather than the “device”

or “instrument” of the policy. In these two cases, the ideological positions taken by members of Congress prevented them from asking the hard questions when it came to execution of the project.

4. Poor contractor hiring practices can threaten projects

Both projects suffered from unproductive relationships with their contractors. The FBI contracts were far too generous. They had a cost-plus-award fee contract, which paid the cost of all labor and materials in addition to other bonuses. The contract also included a provision that if the time frame was lengthened or the contractor incurred additional, unforeseen costs, the FBI was responsible for the overruns. Additionally, the FBI continually made adjustments to the project requirements up to the third year of the project, which meant that contractors constantly had to go back and modify work that was already finished.

For HealthCare.gov, contractor relationships were flawed and contentious. There were over 50 contractors and subcontractors engaged in the project which made the work deeply fragmented. The haphazard nature of the project can be attributed to the way in which contractors worked with CMS and HHS on their work. Infighting between CMS and HHS, spilled over to contractors who, at times, did not have adequate guidance or access to information.

5. Ignoring warning signs

Officials ignored the protestations of people involved in the project. Matthew Patton, an employee of a VCF contractor, posted information online about his company’s habit of using government funds to do work that was not needed. David Cutler, a former advisor on the Obama campaign, sent a memo to White House officials outlining reasons why an outside entity should be engaged to oversee the integration of the various components of HealthCare.gov; both admissions fell upon deaf ears.

Oftentimes, employees engage in the normalization of bad behavior so it enables them to not deal with the fact that things are going poorly. Throughout a 2014 report from the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform on the HealthCare.gov rollout, there were emails from leaders from HHS and CMS acknowledgement of failure and actively seeking to cover it up or quell concerns. One HHS employee even recommended to HHS that they declare victory without fully launching the website.

Newly enacted legislation such as the Federal Information Technology Acquisition Reform Act (FITARA) cede more power and responsibility to CIOs to prevent failures such as HealthCare.gov and VCF. FITARA requires the CIO to be the certifying authority and enforcement power over their agency’s technology investment and development. This new level of empowerment is an effort to get the right people in control of the resources to produce successful outcomes. After HealthCare.gov, the Obama administration created the Smarter IT Delivery agenda, 18F, the U.S. Digital Service Office, TechFar, and the Digital Services Playbook. Additionally, the Office of Management and Budget has been promoting the adoption of agile software development.

The lessons and insights gleaned from both projects should serve as lessons for how to avoid future IT project failures. Large IT solutions are needed to move the public sector forward. However, we must match our hopes for our large IT projects with the proper resources to ensure that work is done well. In addition, we should use the openness and accountability measures of government to put forth scrutiny onto these projects that don’t stifle leaders but insures they are moving in the right direction.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Mega-Scale IT projects in the public sector

May 28, 2015