Executive summary

This report assesses whether the Trump administration’s second-term approach toward China has produced measurable gains for the United States after one year. It evaluates the administration’s four stated objectives: reindustrializing the U.S. economy, maintaining leadership in artificial intelligence (AI), reducing strategic dependencies on China, and restoring U.S. global standing. The report does not challenge or critique the objectives the administration has set for competing with China. Rather, it measures the United States’ performance against the objectives the administration has identified.

The findings point to a consistent pattern across policy domains: ambition and rhetoric have outpaced tangible results. On reindustrialization, the administration has elevated manufacturing as a strategic priority and publicized trillions of dollars in corporate and foreign investment pledges. Yet key indicators—including manufacturing employment, construction momentum, capacity utilization, and industrial production—have yet to show a sustained expansion of the manufacturing sector. Many headline investment commitments remain nonbinding, repackaged, or subject to domestic and political constraints at home and among allies. At the same time, tariff and policy volatility, as well as cost pressures, continue to deter long-term private investment.

In AI, the United States retains advantages in frontier compute, chip design, and leading platforms. But these strengths are increasingly constrained by policy inconsistency, particularly shifting export controls that risk diluting long-term competitive advantages over China. Domestic energy bottlenecks are slowing the scale-up of AI infrastructure, while visa uncertainty and a constrained research environment are weakening the talent pipeline. Meanwhile, China is consolidating a more self-sufficient AI ecosystem and expanding global adoption of its AI technologies through bundled, state-backed offerings.

Efforts to reduce strategic dependencies—highlighted by China’s rare-earth export controls—acknowledge real vulnerabilities but face deep structural barriers. Building alternative supply chains, particularly downstream processing and manufacturing, requires timelines and policy consistency that exceed short political cycles.

Finally, global polling data challenge claims that the United States is “respected again.” Favorability toward the United States has declined sharply among allies, while perceptions of China’s economic influence have risen. This shift is weakening Washington’s ability to mobilize U.S. partners around the administration’s core objectives, such as attracting investment to support American reindustrialization, sustaining a leading edge in AI, and coordinating resilience against Chinese dominance of critical resources and supply chains.

Overall, the Trump administration’s first year record shows strong signaling but limited durable gains. Turning rhetoric into results will hinge on follow-through in the second year, with sustained execution, policy stability, and restoring domestic and international confidence.

Introduction

After one year of sweeping tariffs, investment diplomacy, and technology initiatives, has the Trump administration measurably strengthened America’s industrial base, technological edge, and global influence in relation to China?

This question sits at the core of the Trump administration’s second-term economic and national security agenda. Experts often argue that the administration lacks a coherent “China strategy,” and point out that the 2025 National Security Strategy (NSS) avoids explicitly labeling China as the United States’ foremost strategic competitor. Even so, there is little doubt that China looms large in many of the administration’s consequential domestic and foreign policy decisions. From trade and industrial policy to artificial intelligence and supply-chain security, Beijing functions as the implicit benchmark against which American strength, vulnerability, and leverage are measured.

The Trump administration’s approach rests on a clear diagnosis articulated in the 2025 NSS. It argues that “three decades of mistaken American assumptions about China”—including opening U.S. markets, encouraging U.S. firms to invest in China, and offshoring manufacturing—helped create a “rich and powerful” competitor while hollowing out U.S. industry, weakening economic autonomy, and exposing national security vulnerabilities. Rather than framing its response in abstract terms as “great power competition,” the administration has emphasized that it will rebalance the U.S.-China economic relationship and restore American strength through concrete actions. These include reindustrializing the United States, asserting dominance in critical technologies such as AI, reducing dependence on Chinese-controlled supply chains, and restoring respect for the U.S. abroad.

This report evaluates whether these objectives are beginning to translate into measurable outcomes during the first year of President Donald Trump’s second term. Across each area, it compares official claims and headline announcements with observable indicators—including manufacturing employment and output, investment and capacity utilization, supply-chain vulnerabilities, AI infrastructure and talent trends, and international and domestic polling on U.S. influence and China’s relative standing. The report does not challenge or critique the objectives Trump has set for competing with China. Rather, it measures America’s performance against the objectives Trump has identified.

The findings point to a consistent pattern: while the Trump administration has elevated these priorities and applied a forceful policy toolkit, rhetoric is outpacing results. Progress in advancing Trump’s stated objectives vis-à-vis China has been constrained by implementation timelines, policy uncertainty, structural market dynamics, infrastructure bottlenecks, and growing skepticism among U.S. partners, among other factors. The evidence suggests that rebalancing the U.S.-China relationship and restoring American strength will depend not only on tariffs, executive orders, and high-profile investment announcements, but also on sustained execution, policy consistency, and building capacity and credibility at home and abroad.

Goal 1: Reindustrializing the United States

A central pillar of the Trump administration’s China strategy is the conviction that decades of globalization—driven by China’s export-led industrial rise and enabled by previous U.S. policy choices—hollowed out American manufacturing, weakened the middle class, and left the United States economically and strategically exposed. Trump has articulated this view forcefully across both terms. In one of his sharpest first-term statements, he argued, “China raided our factories, offshored our jobs, gutted our industries, stole our intellectual property, and violated their commitments under the World Trade Organization.” The administration’s central diagnosis is that China’s rise came at America’s expense, and that reversing this dynamic is essential to restoring national strength.

Against this backdrop, reindustrializing the United States and “bringing back American manufacturing” has been a central objective of Trump’s second-term agenda. In the administration’s view, a strong industrial base is the foundation of “economic and military preeminence.” These themes run throughout its national security strategy and its trade and industrial policies. As U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer stated at the 2025 Reindustrialize Summit in Detroit, “A robust manufacturing sector is critical if we are to remain a free and prosperous country.” And to this end, the White House has deployed sweeping tariffs and export controls, and courted investment deals with corporations and foreign governments, with the intention of catalyzing U.S. reindustrialization.

This section evaluates whether the administration’s strategy has begun to deliver measurable progress. Have “jobs and factories” come “roaring back” to the United States, as Trump declared they would at his April 1, 2026, press conference announcing a sweeping round of global tariffs? The analysis reviews recently announced corporate and foreign investment commitments as well as early evidence from manufacturing employment, construction spending, and industrial capacity utilization, among other indicators, to evaluate whether the first year of Trump’s second term has materially advanced a revival of U.S. manufacturing and reduced reliance on China.

Big investment pledges, uncertain outcomes

The Trump administration has pointed to an extensive list of investment commitments from major corporations and foreign governments as evidence that U.S. manufacturing is returning. Featured on the White House’s “Major Investment Announcements” webpage and promoted as the result of the so-called “Trump Effect,” these pledges are widely presented as proof that the administration’s economic policies are successfully redirecting global capital toward new investments in “U.S. manufacturing, technology and infrastructure.”

On the corporate side, several major firms have announced high-profile reshoring and expansion plans. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) has pledged up to $165 billion in U.S. semiconductor investment, including three fabrication plants, two advanced packaging facilities, and an R&D center, as an expansion to its existing operations in Arizona. The company broke ground on its third U.S. fab in April 2025—one of the clearest cases where a major headline commitment has translated into physical construction. Apple has announced a $600 billion U.S. investment program over the next four years, projected to generate 450,000 jobs, and as part of a new “American Manufacturing Program” aimed at strengthening the domestic silicon supply chain. General Electric has also committed about $3 billion to shift portions of its production footprint from China and Mexico to the United States. These are just a few of the announcements made by major companies in recent months.

Yet many of the administration’s touted investment totals may not represent genuinely new investments. Firms have strong incentives to announce large commitments that signal political alignment, and many headline figures repackage existing commitments from projects that had been announced in previous years or include normal operating costs. As Jeffrey Sonnenfeld and Steven Tian of Yale observe, CEOs have been repackaging existing spending plans into “gauzy headline-drawing big number[s] to appease Trump superficially, tossing in everything from normal operating expenses to employee salaries to inflate their headline amounts, while actually suspending new investment plans in practice.”

Even where commitments are new, follow-through remains uncertain. At a closed-door gathering of senior executives hosted by the Yale School of Management in September, 62% of business leaders reported that they were not planning to increase U.S. manufacturing or infrastructure investment. Most cited tariff volatility and policy uncertainty as primary deterrents. As Susan Spence, chair of the Institute for Supply Management’s Manufacturing Business Survey Committee, put it, “From the time a company decides to build a new factory, and the time it’s open, it could be three to five years, and the policies could be completely changed … There’s uncertainty. People stay still. They don’t invest.” Cost pressures pose significant barriers as well. High U.S. labor costs, combined with tariff-driven increases in the price of intermediate goods and raw materials, complicate efforts to reshore production, even for firms publicly aligned with the administration’s goals. Even where projects are moving forward, it remains uncertain how much of the headline value of these investment commitments will ultimately be realized.

Foreign-government investment packages—another pillar of the administration’s reindustrialization strategy—carry similar uncertainties. The White House’s investment announcements webpage advertises roughly $5.75 trillion in commitments from foreign counterparts from the Middle East to Europe to Asia. At face value, these deals appear to represent extraordinary momentum behind U.S. industrial revival.

In May 2025, the White House announced that the president had secured $2 trillion in investment commitments during his Gulf tour, and the administration’s investment webpage prominently highlights headline pledges from the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia. Yet, as experts caution, many of these announcements rest on broad, long-horizon investment frameworks rather than binding project-level commitments. Analysts note that the headline figures often combine potential future spending with preexisting investment plans. Nonbinding memoranda of understanding are also frequently presented as firm capital inflows, as opposed to the more traditional measures of realized foreign direct investment into the United States.

The Trump administration’s agreements with Asian allies, particularly with Japan and South Korea, are more detailed and structured than the Gulf commitments, but they introduce a different set of concerns. Although these packages come with formal fact sheets and implementation mechanisms, early reactions in both countries reveal public unease over sovereignty, financial exposure, and the economic returns of the proposed investments. There are also signs that domestic scrutiny, legal challenges, and political pressure on national leaders may constrain or slow follow-through on the agreements, raising questions about how durable these commitments will ultimately be.

Japan’s widely publicized $550 billion commitment illustrates these concerns. A White House fact sheet from July 2025 describes the arrangement as a sweeping investment program to be “directed by the United States,” with 90% of the profits accruing to the United States. A subsequent memorandum of understanding (MOU) released in September by the two governments has intensified criticism inside Japan. The MOU states that a U.S.-run investment committee will be empowered to select projects unilaterally, limits Japan’s formal consultation window to 45 business days, and authorizes Washington to reimpose tariffs if Tokyo declines to finance U.S.-chosen ventures.

Japanese analysts and industry leaders have described the structure as an “unequal treaty,” warning that it places significant financial risk on Japan without granting corresponding control over project selection or management. Others note that Tokyo may ultimately resort to “symbolic participation,” stalling, and “finding ways to kick the can down the road” until the next administration. Tokyo’s own characterization has diverged sharply from that of the Trump administration, with Japanese officials emphasizing that only 1%-2% of the package would take the form of direct equity investment, while the remainder will consist of loans and loan guarantees. The investment funds will be issued by the Japan Bank for International Cooperation, and loan guarantees will be provided by the Nippon Export and Investment Insurance. Contrary to the Trump administration’s characterization that Washington will “direct” the deployment of capital, Japanese officials have underscored that these state institutions must operate under Japanese legal guidelines, must conduct independent commercial risk assessments, and can only finance projects deemed commercially viable and consistent with Japan’s own national and economic interests. The gap between the U.S. and Japanese characterizations of the deal raises questions about implementation, control, and the commitment’s durability once political and commercial realities assert themselves.

South Korea’s investment package exhibits similar tensions. Trump initially claimed that Seoul had agreed to invest $350 billion in the United States that would be “owned and controlled by the United States, and selected by myself, as President.” But the actual MOU released by both sides in November paints a different story. Under the deal, $150 billion would be directed to investments in shipbuilding, and $200 billion would be allocated to investments selected by an investment committee chaired by the U.S. secretary of commerce. But the $200 billion would be phased over time, capped at $20 billion per year to limit financial exposure, effectively stretching the timeline over a decade. The MOU also stipulates that Seoul may decline to fund an investment “in its sole discretion.”

Korean industry representatives have also expressed concerns about the absence of firm timelines and transparent cost assessments, as well as heightened political sensitivity following the Hyundai plant ICE raid in September 2025. Domestic backlash to the MOU is already visible, with opposition lawmakers insisting that the agreement requires parliamentary ratification, warning that Seoul must have sufficient oversight over how the $200 billion investment is structured and managed.

The $600 billion investment deal with the European Union (EU) displays a similar pattern of inflated expectations. Characterized by Trump as a “gift” by the EU, to be used for “anything we want,” the actual framework agreement released in August 2025 states only that private European companies are “expected to invest” $600 billion in the United States through 2028. The figure is nonbinding and reflects broad industry “intentions,” not guaranteed capital flows.

These uncertainties are compounded by deteriorating transatlantic relations. The Trump administration’s 2025 National Security Strategy took an unusually hostile tone toward Europe—prompting some European leaders to describe it as a “declaration of political war” and to warn that the “Western alliance is over.” Additional strain has come from the Trump administration’s ambitions to annex Greenland, a move that has shocked European capitals. Together, these developments risk dampening Europe’s appetite for deeper economic engagement with the United States, casting serious doubt on whether these notional investment commitments will be realized.

In sum, while the headline investment numbers are striking, the underlying agreements vary widely in credibility, clarity, and enforceability. Many rely on nonbinding frameworks, divergent expectations, or face domestic political resistance in partner countries that could delay, reshape, or even block implementation. These risks are heightened by questions among U.S. allies about the durability of American commitments and shifting U.S. foreign and economic policies. Whether these deals ultimately contribute to a sustained U.S. industrial revival—or remain largely symbolic—will hinge on commercial viability, the durability of political trust between the United States and its partners, and sustained implementation efforts by all parties.

Bold rhetoric on manufacturing and jobs, limited signs of a turnaround

While the administration points to corporate and foreign government investment commitments as evidence of a manufacturing revival, real-economy indicators offer a more grounded test of progress. This section examines core measures of U.S. manufacturing activity: employment, construction spending, capacity utilization, and industrial production—to evaluate whether reindustrialization is occurring at scale. Across all indicators, the data show stagnation rather than expansion, suggesting that headline commitments have not yet translated into measurable gains in U.S. industrial activity.

Manufacturing employment in the U.S.

According to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, U.S. manufacturing employment has declined by roughly 58,000 jobs since Trump returned to office in January 2025. While month-to-month fluctuations are expected, a sustained contraction of this size is difficult to reconcile with claims of a broad-based industrial resurgence. Rather than signaling renewed factory activity, the employment trend suggests that the administration’s reindustrialization agenda has yet to translate into increased hiring.

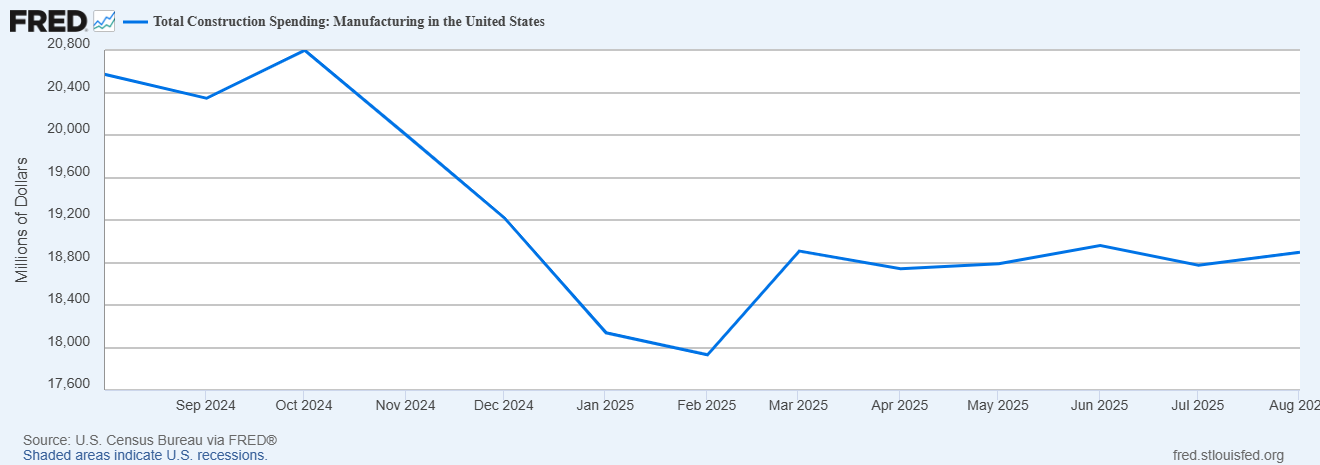

Manufacturing construction spending over the past year

Manufacturing construction spending, past five years

Manufacturing construction spending—investment in new plants and expansion of existing plants—offers insight into where firms are committing long-term capital. Factory construction is typically the leading edge of a manufacturing upturn. A meaningful reshoring wave would likely generate large, sustained increases in construction as firms initiate multiyear projects.

Monthly spending on manufacturing construction remains historically high, averaging $18.6 billion per month since Trump’s return to office, compared with $13.5 billion per month over the previous five years. However, there has been no renewed upward momentum over the past year. Spending has instead plateaued following the earlier surge and remains below the $20.8 billion peak reached at the end of the previous administration. The absence of a new construction wave suggests that much of the current activity reflects projects already underway rather than an acceleration in new factory starts. Industry commentary, as discussed above, indicates that policy uncertainty, particularly regarding tariffs, continues to inhibit major capital expenditures.

Manufacturing capacity utilization

Capacity utilization measures how intensively firms are using their existing facilities. Historically, firms move to expand production capacity when utilization rises above 80%-82%, signaling demand sufficient to justify new investment. During Trump’s second term, manufacturing utilization has hovered between 74% to 76%, below the typical threshold that calls for rapid expansion in capacity.

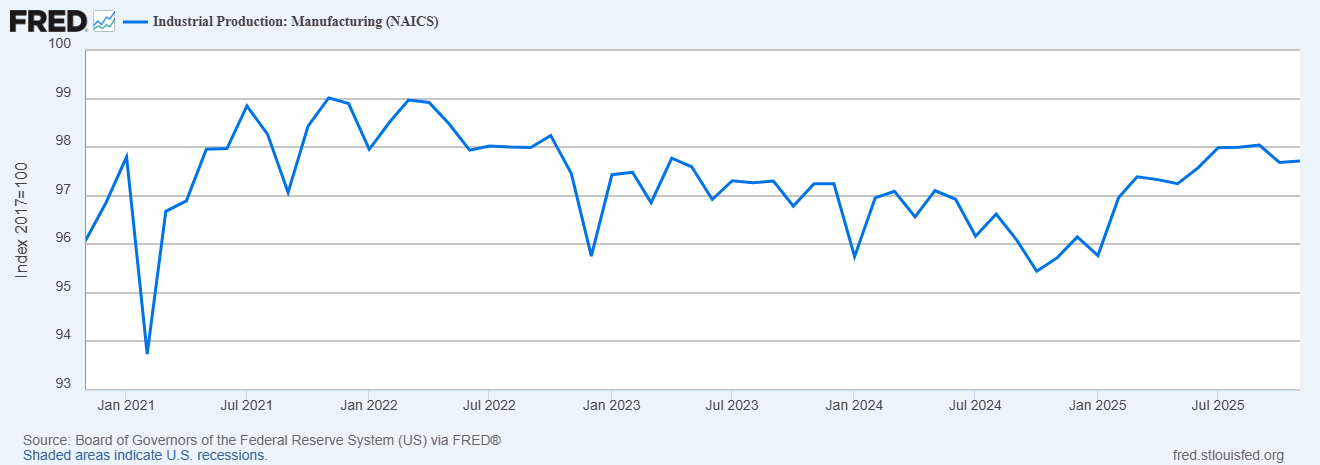

Industrial production: manufacturing, past year

Industrial production: manufacturing, past five years

The Federal Reserve’s Industrial Production Index for manufacturing measures the physical volume of manufacturing output relative to a base year, with 2017 set equal to 100. This means that an index value of 100 corresponds to the average level of manufacturing output in 2017, while values above or below 100, respectively, indicate higher or lower output than the 2017 average.

By this measure, U.S. manufacturing output over the past year shows modest movement but remains below the 2017 benchmark. In practical terms, this suggests that despite high-profile investment announcements and policy rhetoric centered on reindustrialization, aggregate manufacturing output has not surpassed the pre-pandemic benchmark. The longer-term, five-year series shows a similar pattern: manufacturing output has fluctuated within a narrow range, with no sustained upward breakout.

Sentiment surveys of industry participants also indicate a sector paralyzed by policy and tariff volatility. The Institute for Supply Management’s (ISM) Purchasing Manufacturers’ Index, a key indicator of the health of the U.S. manufacturing industry, contracted for much of the last year, largely attributed by manufacturers to Trump’s tariffs.

Manufacturing purchasing managers responding to surveys conducted by ISM cited tariffs as weighing on planning, sales, and costs. Respondents noted that recent price increases have largely served to offset tariff-related costs rather than improve margins, and that persistent instability in trade and economic policy has frozen capital expenditures and hiring decisions. The survey also found that tariffs have hit the transportation industry particularly hard, leading many companies to pursue manufacturing overseas rather than reshoring to the United States.

Across all indicators, the evidence is consistent and mutually reinforcing. Employment is declining, construction spending has plateaued, capacity utilization is below levels that typically spur new investment, and industrial production shows only marginal gains. Rather than a manufacturing renaissance, the data depict a sector that is stable at best, but not expanding, and constrained by policy uncertainty, elevated input costs, and insufficient demand.

The Trump administration has undoubtedly succeeded in elevating manufacturing as a strategic priority and in securing a series of high-visibility investment announcements. Yet these commitments have not yet translated into measurable improvements in U.S. manufacturing in the first year of Trump’s first term. The gap between rhetoric and real-economy indicators remains wide, raising questions about the effectiveness of current policy tools.

How does U.S. manufacturing performance compare to China’s?

Although the United States and China have fundamentally different economic structures—and the United States neither seeks nor needs to replicate China’s manufacturing scale—relative performance is an important benchmark for assessing whether Washington is narrowing or widening the gap with Beijing in global industrial competition. China remains the world’s largest manufacturing economy by a wide margin, and the available 2025 data indicate that this gap in output growth and global market share is continuing to widen.

China’s manufacturing sector occupies a central position in its economic model. Manufacturing accounted for around 25% of China’s GDP in 2024, compared with roughly 10% of the United States. This difference reflects decades of national strategy: beginning with Reform and Opening in the late 1970s, Beijing pursued export-oriented industrialization, large-scale foreign-investment attraction, and systematic upgrading of domestic industries. China’s share of global manufacturing output rose from under 9% in 2004 to become the world’s leading manufacturing power by 2011, and it has continued consolidating that position ever since.

Upgrading China’s manufacturing capability has remained a central priority, as shown in the Made in China 2025 initiative, launched in 2015, that sought to elevate China from low-end to advanced high-tech manufacturing. The priorities set out in China’s most recent five-year plan reinforce this trajectory by elevating advanced manufacturing as the backbone of a modernized industrial system, prioritizing emerging sectors such as AI, 5G, new energy, and biomedicine, and accelerating breakthroughs in core technologies through innovation and digital integration.

China’s manufacturing momentum in 2025 has also been reinforced by a strong export year. China recorded a goods trade surplus exceeding $1 trillion through November, the largest in its history. Even as direct exports to the United States fell nearly 20% due to tariffs, China more than made up for these losses via rapid export growth to Southeast Asia, Africa, Latin America, and parts of Europe. This diversification enabled Chinese factories to remain at high utilization levels, offsetting weaknesses in domestic consumption. Viewed collectively, the 2025 data point to a widening, not narrowing, manufacturing performance gap between the United States and China.

Goal 2: Racing ahead of China in AI

The Trump administration has framed leadership in artificial intelligence as a decisive arena of geopolitical competition, repeatedly casting China as the United States’ principal challenger. Trump has declared that “China and other countries are racing to catch up to America on AI, and we’re not going to let them do it.” Senior officials, including AI adviser David Sacks, have emphasized that “China is our main competition globally in this AI race.” The administration’s AI Action Plan identifies three pathways to “winning”: accelerating innovation, building physical infrastructure to support AI energy and chip demands, and ensuring global adoption of U.S. AI technologies.

This section evaluates how the administration’s actions affect the United States’ long-run AI advantage across three core metrics: compute and infrastructure, talent and research quality, and diffusion and deployment.

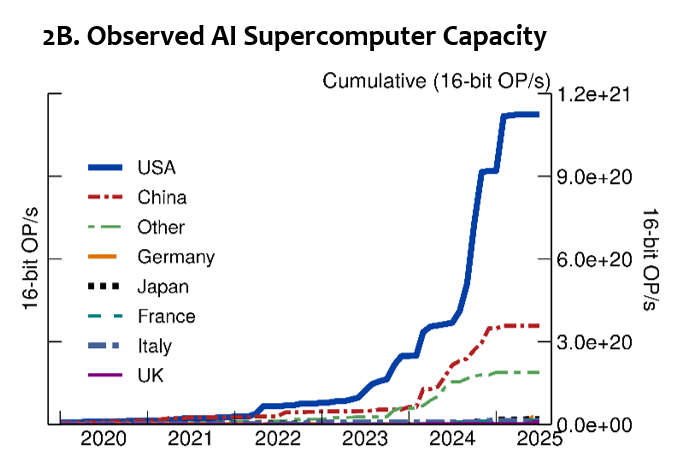

Maintaining a leading edge in compute?

Compute remains a key binding constraint in frontier AI development. Access to advanced GPUs, data centers, reliable energy, and high-speed networking determines not only which models can be trained but how rapidly firms can scale and deploy them. On this dimension, the United States retains a clear lead. Independent analyses consistently show that the United States hosts the overwhelming majority of the world’s high-end AI training capacity, controlling roughly 74% of global AI supercomputer capacity, compared to China’s 14%.

Observed AI supercomputer capacity across major countries, 2020-2025

Several structural factors underpin this U.S. advantage. First, leading AI chip designers, including Nvidia and AMD, are headquartered in the United States and dominate advanced accelerator design. This position gives U.S. firms preferential access to cutting-edge hardware and provides Washington leverage through export controls and technical standards, constraining China’s ability to aggregate frontier-scale compute.

Second, the United States is home to many “hyperscalers,” such as OpenAI, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon, which are collectively investing hundreds of billions of dollars in data centers and AI training infrastructure to support frontier model development and the large-scale deployment of AI across the economy.

Third, U.S. access to complementary inputs—particularly high-bandwidth memory (HBM) and advanced networking hardware—reinforces its advantage. U.S. export controls on HBM have emerged as one of the most binding constraints on China’s ability to develop and produce advanced AI chips at scale. Because HBM is an essential component of AI accelerators, continued U.S. control over HBM supply chains compounds America’s advantage in frontier AI training and deployment, even as China seeks to narrow gaps in individual chip or model performance.

For now, the United States leads in AI compute, but whether this advantage endures will also depend on U.S. infrastructure and export control policies, as well as China’s own efforts to develop domestic AI chips.

Export controls and the compute trade-off

The administration’s evolving approach to Nvidia chip exports highlights a deeper tension in U.S. AI policy. Over the course of 2025, the administration both tightened and selectively relaxed export controls. In April 2025, the administration first increased restrictions on Nvidia’s AI chips by halting exports of the H20 to China; it then reversed course in July, allowing limited shipments of the downgraded chip to resume. By December 2025, the administration further eased controls by approving conditional exports of the more advanced H200 chips. These changes highlight an ongoing tension between two competing objectives: slowing China’s access to advanced AI compute and preserving U.S. firms’ market share, sustaining revenues, and keeping Chinese users dependent on U.S.-designed technology, rather than on domestic alternatives such as Huawei.

The reversals have gotten particularly strong pushback from former U.S. officials and the broader expert community. Former National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan warned that “China’s main problem is they don’t have enough advanced computing capability. It makes no sense that President Trump is solving their problem for them by selling them powerful American chips. We are literally handing away our advantage.” Such policies risk undermining U.S. advantages while introducing uncertainty for U.S. firms.

At the same time, it is also unclear how much uptake these newly accessible chips will have in China. Beijing has made clear that technological self-reliance—including reducing dependence on U.S. chips—is a strategic priority. That stance has already been reflected in China’s limited uptake of Nvidia’s H20 chips after export controls were eased last year, as regulatory signals from Beijing discouraged purchases and prevented meaningful adoption. For the most recent round of H200 chips, Beijing has neither publicly approved nor rejected imports of Nvidia’s H200 products following the U.S. policy change. While Chinese regulators have discussed permitting limited access, it remains unclear how many—if any—will ultimately be purchased.

The latest reports suggest that Beijing has unofficially banned the sale of the H200 chips. However, some analysts believe this may be a bargaining tactic as Beijing prepares for trade talks with Washington later this year. As Chinese commentators note, “The US could lift restrictions and authorize H200 sales to China today, only to ban them again tomorrow.” This reality reinforces reluctance among Chinese firms to commit to U.S. technology. If these trends persist, it is unclear whether the administration can achieve its dual objectives of economic gain for American firms and sustained technological leverage.

AI infrastructure push and constraints

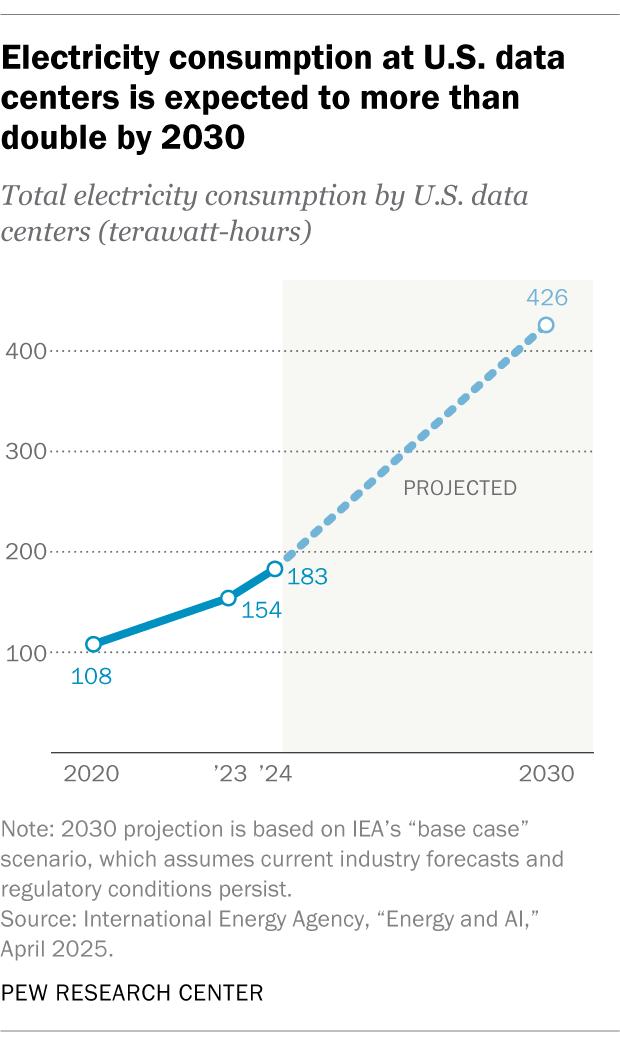

Sustaining U.S. advantage in compute carries significant energy demands. Leadership in AI depends not only on chips and models but also on the physical infrastructure that underpins compute at scale: data centers, electric grid capacity, and reliable energy generation. Over the past year, the Trump administration has moved to accelerate AI infrastructure buildout. At the federal level, the AI Action plan and related executive orders call for the rapid buildup of data centers and supporting energy infrastructure by streamlining environmental reviews, fast-tracking permits for data centers and energy infrastructure, and encouraging the rapid expansion of electricity supply. The administration has framed this push in explicitly geopolitical terms, arguing that regulatory delay risks ceding ground to China in the AI race.

Yet many of the most consequential decisions governing AI infrastructure lie outside direct federal control. State and local governments retain authority over data-center siting, water access, grid interconnection, and utility rate-setting, limiting the effectiveness of federal permitting reforms alone. This constraint has become increasingly visible as local governments have rejected or delayed major AI data-center projects despite strong national-level pressure to accelerate deployment.

In December 2025, for example, Trump signed an executive order establishing a “national policy framework for AI” and creating a “AI Litigation Task Force” to challenge state laws deemed to impede U.S. “global AI dominance.” On the same day, the city council of Chandler, Arizona, unanimously rejected a proposed AI data-center project after sustained local opposition. Residents cited concerns over water use, electricity demand, and community impact, despite intensive lobbying and the project’s alignment with national AI priorities. Similar resistance has emerged across multiple states, including in jurisdictions that voted for Trump. Communities have raised concerns that large data centers threaten farmland, impose environmental and resource costs on residents, and deliver limited local economic benefits. Reporting suggests that this opposition has stalled or blocked more than $60 billion in proposed projects. In Florida, Governor Ron DeSantis has proposed state legislation—“AI Bill of Rights”—to preserve state and local control over data center construction and associated energy costs. Legal experts note that the most recent executive order will likely be contested in court by states and consumer groups.

The concerns at the state and local levels are not unfounded. Electricity consumption at U.S. data centers is projected to more than double by 2030, straining grids, raising energy costs, and increasing reliance on fossil fuels. A Cornell study estimates this expansion could add 24 million to 44 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually, the equivalent of putting up to 10 million additional cars on the road. In water-stressed regions, data-center cooling demands are also projected to exacerbate local shortages.

Beyond environmental and local political constraints, the U.S. infrastructure system’s structure also shapes how rapidly AI capacity can scale. Unlike in China, where infrastructure development is state-driven, the U.S. model relies primarily on private investment and decentralized decisionmaking. In practice, the administration’s infrastructure strategy relies heavily on private-sector investment by hyperscalers, with federal policy playing an enabling rather than a coordinating role. U.S. infrastructure expansion remains decentralized and individually negotiated among firms, utilities, regulators, and local governments, which limits the federal government’s ability to ensure rapid or uniform buildout even amid aggressive national signaling.

China, by contrast, has pursued a centralized and energy-centric approach to AI infrastructure. Since 2010, China’s power generation growth has exceeded that of the rest of the world combined, leaving many Chinese data centers paying less than half the electricity costs of their U.S. counterparts. China is also building a nationwide high-speed computing network that links hundreds of data centers—allowing AI workloads to be routed across regions and effectively pooled into a shared national compute system. Facing restricted access to leading-edge AI chips, Chinese firms have increasingly turned to bundling and stacking large numbers of less-advanced processors, including domestically produced chips, to scale training workloads through volume rather than per-chip performance. While this approach is less efficient and faces limits, it allows China to partially offset chip constraints by substituting cheaper and more abundant energy for single-chip performance.

In sum, the Trump administration has elevated AI infrastructure as a national priority and moved to reduce federal-level barriers through executive action. However, the decentralized nature of U.S. infrastructure governance—combined with environmental constraints, energy bottlenecks, and local political resistance—remains a significant challenge to achieving the rapid, large-scale buildout needed to sustain U.S. leadership in AI relative to China.

Talent and research quality under strain

While compute enables scale, talent determines breakthroughs. Leadership in AI ultimately rests on the ability to attract, retain, and coordinate elite researchers who set the pace of innovation. For decades, the United States has held a decisive advantage in this domain—one that remains significant but is increasingly under strain.

Historically, the United States has dominated global AI research due to the concentration of leading AI labs, such as OpenAI, Google DeepMind, and Anthropic, within its borders, alongside universities that remain premier centers for machine learning research and training. This ecosystem has been further strengthened by the country’s ability to attract a disproportionate share of top technical talent, particularly from China, reinforcing U.S. leadership across both cutting-edge research and talent development. This remains a core U.S. advantage, but it is eroding.

Recent evidence points to mounting strain on the U.S. research and talent pipeline. In a March 2025 Nature survey of over 1,600 U.S.-based researchers, approximately three-quarters of respondents reported considering leaving the country. The share rose to nearly 80% among postgraduate researchers, even before the latest visa restrictions and budget cuts. Several factors are contributing to this trend, including growing visa uncertainty, cuts to federal research funding, and the increasing politicization of scientific agencies, all of which have undermined confidence in the U.S. research environment.

These pressures are increasingly visible in international student flows. U.S. universities recorded an approximately 19% drop in international student arrivals in August 2025, the largest drop outside of the COVID-19 pandemic. The sharpest declines were international student arrivals from Asia, with a 12% drop in students from China and a 44% drop in students from India—two countries that supply a substantial share of graduate-level science, technology, engineering, and math talent. Rising barriers for these students have constrained universities’ ability to replenish the talent pipeline that feeds both academic research and the private AI sector.

While many international researchers continue to remain in the United States despite these challenges, the direction of travel is concerning. As Matt Sheehan, an expert on global technology issues, has observed, “The U.S. A.I. industry is the biggest beneficiary of Chinese talent … It gets so many top-tier researchers from China who come to work in the U.S., study in the U.S. and, as this study shows, stay in the U.S., despite all the tensions and obstacles that have been thrown at them in recent years.” Sustained erosion of this inflow would materially constrain the United States’ long-term AI capacity. Absent a coherent strategy to stabilize immigration pathways and protect the research ecosystem, the United States risks weakening the very foundation that has historically underpinned its AI leadership.

China’s increasingly self-sustaining talent base

In contrast, China has intensified its efforts to build a self-sustaining domestic AI talent and research ecosystem. The government has mobilized billions in funding across state-owned enterprises, private firms, and state and local governments to support “hard tech” sectors such as semiconductors and AI. China has also expanded its educational pipeline at scale. More than 600 colleges in China now offer AI degree programs, up from just 35 in 2019. Importantly, an increasing share of Chinese AI researchers are no longer passing through the United States for education or early-career training. Studies indicate that more than half of the researchers behind recent Chinese AI breakthroughs—such as DeepSeek—completed their education and careers entirely within China.

Additionally, while U.S. universities have historically held the lead in AI research, and continue to do so, producing 40 top AI models in 2024 compared to China’s 15, the gap is narrowing. Tsinghua University alone reportedly generated more than 900 AI and machine learning patents last year, and consistently files more patents each year than MIT, Stanford, Princeton, and Harvard combined. While patent counts do not directly equate to breakthrough capability, they reflect the growing momentum of China’s research ecosystem.

These trends suggest that while the United States has a meaningful edge in elite AI talent and research quality, that advantage is increasingly fragile. Policies that introduce uncertainty into immigration, reduce federal research funding, or politicize scientific institutions risk accelerating talent attrition at precisely the moment when China is consolidating its domestic talent base.

Competition in international diffusion

Beyond domestic capability, a decisive dimension of the AI race lies in international diffusion: whether other countries adopt U.S.-aligned or China-aligned AI systems, infrastructure, and standards. Recognizing the strategic importance of adoption, the Trump administration has made international diffusion a central pillar of its AI strategy. In describing U.S. objectives, White House Office of Science and Technology Policy Director Michael Kratsios argued that “adoption” is key to “winning the AI race.”

To that end, in July 2025, the administration issued an executive order aimed at accelerating exports of what it terms “American AI tech stacks.” These stacks bundle U.S.-designed chips, AI models, cloud services, software applications, and technical standards into integrated offerings intended to anchor partner countries within U.S.-aligned technology ecosystems rather than Chinese ones. Export packages prioritized through the Department of Commerce will be eligible for federal resources such as loans, loan guarantees, equity investments, and technical assistance.

Despite strong American intent, international adoption of U.S. systems is constrained by several factors. First, frequent shifts in U.S. trade, technology, and alliance policy—combined with a more transactional diplomatic posture—have encouraged both advanced economies and emerging markets to pursue diversification strategies. As analysts point out, major markets such as India and the European Union increasingly seek to limit dependence on both Washington and Beijing, complicating efforts to build a cohesive U.S.-led AI bloc.

Second, many U.S. allies—particularly in Europe—have sharply diverged from the Trump administration’s deregulatory approach by adopting AI governance frameworks that emphasize risk classification, data protection, and safety requirements. The administration has framed minimal regulation as central to U.S. AI leadership. Vice President JD Vance reinforced this stance at the February AI Action Summit in Paris, and it was codified in a January executive order rolling back prior AI policies viewed as barriers to innovation, as well as in the AI Action Plan’s focus on removing “red tape.” As U.S. AI governance moves toward emphasizing deregulation, growing divergence with allied regulatory regimes may reduce regulatory interoperability and undermine confidence in adopting U.S. AI systems.

Third, cost and financing terms shape adoption decisions, particularly in emerging markets. China frequently bundles AI systems with concessional financing, infrastructure construction, and long repayment timelines, lowering barriers to entry for cash-constrained governments. U.S. offerings, by contrast, are often priced at commercial rates and rely more heavily on private financing, limiting competitiveness in markets where upfront cost and financing flexibility outweigh frontier performance. While the July 2025 executive order states that the United States will align “technical, financial, and diplomatic resources” to promote the export of AI tech stacks, the administration has yet to deploy concrete financing programs or indicate a focus on emerging markets.

Meanwhile, China has prioritized rapid AI deployment, particularly in the Global South. In addition to the development of large frontier models, China’s AI strategy also prioritizes a “small yet smart” style of deployment across public-sector applications, industrial automation, smart-city systems, and surveillance platforms, often bundled with state-backed financing associated with the Digital Silk Road. This approach leverages several comparative strengths: the deep integration of AI into industrial and logistics systems, government procurement that creates large and stable domestic markets for Chinese firms, and export packages that combine hardware, software, cloud services, and financing. Once deployed, these systems tend to create sticky, long-term technological dependencies, reinforcing China’s influence even without leading at the frontier of model development.

On the software side, China still lags behind the United States in establishing mature, globally adopted AI software ecosystems. However, the release of DeepSeek’s R1 model marked a notable shift. Following the release of DeepSeek R1, many Chinese AI labs have pursued an open-source approach to AI development. By offering powerful AI models at little to no cost, Chinese firms have been gaining share in global adoption, from Asia and Africa to Silicon Valley. While this does not immediately translate into state-level alignment or infrastructure dependence, it strengthens China’s position within open-source ecosystems and may influence longer-term patterns of integration and experimentation.

In conclusion, the evidence indicates that while the Trump administration has correctly identified AI as a central arena of strategic competition with China, its approach produces an uneven balance of strengths and vulnerabilities. The United States retains meaningful advantages in frontier compute, elite research capacity, and core AI platforms, but these advantages are increasingly constrained by infrastructure bottlenecks, talent attrition risks, and policy uncertainty. Efforts to translate technical leadership into geopolitical influence through export promotion and “AI tech stack” diffusion remain at an early stage and face structural headwinds, including regulatory divergence among allies and cost and financing disadvantages in emerging markets. In short, there’s a real risk that the United States could maintain leadership at the technological frontier but still watch other countries conclude that China’s models are cheaper, sufficiently capable, and better suited to the practical AI applications they plan to deploy in the coming years.

Goal 3: Reducing strategic dependencies on China

China’s imposition of rare-earth export licensing requirements in April 2025, followed by a broader expansion of controls in October, sent a shock through U.S. industry and policy circles. The restrictions significantly disrupted shipments of critical materials and exposed the degree to which key segments of the U.S. economy remain reliant on Chinese-controlled supply chains. The export controls also crystallized a broader reality: rare earths are only one of several areas in which the United States remains strategically dependent on China, alongside pharmaceuticals, lithium-ion batteries, and mature chips. Rare earths have nonetheless received disproportionate attention precisely because China’s actions in April and October demonstrated its willingness—and ability—to weaponize dominance in a sector critical for both economic competitiveness and national security. Jamieson Greer, the U.S. trade representative, described Beijing’s action as a “global exercise in economic coercion” while Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent framed it as a wake-up call, arguing that the United States “must be self-sufficient, or be sufficient with our allies, within two years.”

In response, the Trump administration articulated an ambitious agenda aimed at rapidly reducing reliance on China, stating the U.S. government would take equity stakes in private companies in strategic industries, while introducing price floors and strategic stockpiles, among other measures. The administration has also claimed that the United States would secure alternative supplies of rare earths within two years.

This section evaluates whether these initiatives place the United States on a credible path toward reducing strategic dependence on China with a focus on rare earths.

The scope of U.S. dependence

China dominates critical mineral supply chains, controlling roughly 70% of rare-earth mining, over 90% of rare-earth processing, and more than 80% of battery manufacturing capacity. For lithium-ion batteries—essential to automotive and green energy sectors—China produces over 60% of key inputs (cathodes, anodes, lithium, cobalt) and 98% of refined graphite.

Even in sectors where the United States and its allies lead, dependencies persist. While advanced semiconductors remain largely outside China’s control, Beijing commands around one-third of mature-node chip capacity—critical for automobiles, industrial machinery, and defense systems—and dominates key semiconductor inputs, accounting for over 99% of global production of gallium and maintaining a leading position in germanium production.

In pharmaceuticals, U.S. dependence is similarly acute. China supplies substantial shares of acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) for antibiotics. Even generic drugs imported from India often rely on Chinese APIs. The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission has warned that disrupted API exports could severely impact U.S. public health.

Rare earths: Progress and structural constraints

Building domestic capacity

Efforts to reduce dependence on rare earths form part of a longer-term Department of Defense (DOD) initiative launched in 2023, aimed at establishing resilient “mine-to-magnet” supply chains by 2027. Since 2020, the DOD has awarded more than $439 million to U.S. firms to support rare-earth mining, separation, and early-stage manufacturing.

Despite these efforts, current U.S. capacity remains limited. Only two firms—MP Materials and Energy Fuels—operate at a commercial scale. While the United States is the world’s second-largest rare-earth producer, largely due to the Mountain Pass mine in California, it remains far behind China. U.S. production is concentrated in light rare earth elements, while China maintains its strongest leverage over heavy rare earths. Although the United States has begun to develop domestic separation capacity, downstream stages—particularly magnet manufacturing—remain overwhelmingly concentrated in China.

This downstream concentration is decisive. Permanent magnets represent the point at which rare earths become economically and militarily indispensable, powering electric vehicles (EVs), wind turbines, consumer electronics, and modern weapons systems. Even substantial progress in mining and separation does not eliminate strategic vulnerability if magnet-grade materials and finished magnets must still be sourced from China.

These challenges are compounded by rising global demand. In 2019, China accounted for 62.9% of global rare earth output, compared with 12.4% for the United States. Since then, China’s dominance has deepened: between 2020 and 2024, it accounted for roughly 96% of the net increase in global refined rare earth production, far outpacing all other producers, as demand surged with the expansion of EVs, wind power, and other magnet-intensive technologies.

Beyond capacity constraints, market economics pose a persistent obstacle to diversification. China’s dominance is reinforced by its ability to sustain low prices through state support, allowing Chinese producers to undercut competitors during downturns and drive non-Chinese firms out of the market. This pricing power has historically discouraged private investment in alternative supply chains, even when resources are available. While the Trump administration has discussed countermeasures such as price floors, long-term offtake agreements, and public equity stakes, these tools have not yet been deployed at a scale sufficient to neutralize China’s market leverage.

The administration’s stated two-year timeline further highlights a mismatch between political ambition and industrial reality. Developing new mines, processing facilities, and magnet-manufacturing capacity typically requires around 15 years, even under favorable regulatory and financing conditions. As Tim Puko, director of commodities at the Eurasia Group, has observed, “Promises of a year or two are either naivety or spin.”

Expanding supply with allies

Recognizing that domestic production alone will be insufficient, the Trump administration has pursued public-private partnerships and allied supply-chain initiatives. In July 2025, MP Materials entered into a major agreement with the Department of Defense involving long-term procurement commitments and billions of dollars in federal investment intended to scale output over the next decade. The U.S. Export-Import Bank also issued a letter of interest for up to $120 million to support the Tanbreez rare-earth project in Greenland, marking the administration’s first overseas mining-related investment.

Beyond these anchor efforts, the administration has pursued a broad set of bilateral arrangements aimed at expanding non-Chinese supply. These initiatives vary widely in credibility and immediacy. Some, particularly agreements with Australia and Japan, include defined timelines, funding commitments, and offtake provisions that could materially support allied production if implemented. Others are more aspirational. The MOU between MP Materials and Saudi Arabia’s Maaden to develop a rare-earth refinery signals intent but remains several years from production.

Deals with Malaysia and Thailand similarly aim to secure stronger joint critical mineral supply chains, though they remain broad and lack binding funding obligations. Malaysia has committed to refraining from banning or imposing quotas on critical mineral exports to the United States, while prioritizing U.S. investment in its critical minerals sector and integrating its resources into U.S.-aligned supply chains. Thailand’s deal gives the United States the “first opportunity to invest” in critical minerals from Thai suppliers, though Thai officials dispute this as a nonbinding gesture of goodwill rather than a legal obligation. While these agreements emphasize cooperation and investment prioritization, they leave substantial discretion with host governments.

Commercial and regulatory headwinds

At the same time, domestic policy choices complicate the commercial viability of U.S.-based and/or non-Chinese supply chains. The phaseout of the Advanced Manufacturing Production Credit under the One Big Beautiful Bill Act weakens the commercial case for scaling high-cost U.S. production. Analysts warn this shortens the investment runway and “weakens the commercial case for expanding domestic rare earth capacity.”

Regulatory challenges further constrain progress. For example, Lynas Rare Earths’ Texas-based processing facility—developed with DOD support—has faced permitting delays related to wastewater disposal, casting doubt on its projected 2026 production timeline. Environmental risks, not just at home but also abroad, pose challenges for projects. In Malaysia, rare-earth operations were suspended in late 2025 following reports of river contamination and radiation levels significantly exceeding safety thresholds.

Rare earths have become the most visible test case of U.S. efforts to reduce strategic dependence on China, sharpened by Beijing’s export controls in April and October 2025 and the exposure of long-standing supply-chain vulnerabilities. While the Trump administration has taken meaningful steps to mitigate this dependence through targeted investment, public-private partnerships, and allied coordination, progress remains uneven and structurally constrained. More broadly, rare earths represent only one dimension of a wider set of strategic dependencies that continue to shape U.S. economic and national security risk. Absent sustained, coordinated action across these domains, efforts to reduce vulnerability in one sector may be offset by persistent exposure elsewhere.

Goal 4: “Respected again”? Global perceptions of U.S. power vis-à-vis China

A central claim underlying Trump’s worldview is that the United States had lost global respect and had been systematically taken advantage of by foreign powers, including China. A large part of his promise to “Make America Great Again” rests on the assertion that restoring U.S. prestige—and ensuring the country is no longer exploited or disrespected—is essential to reestablishing American strength on the world stage. This logic has remained consistent from Trump’s earliest political messaging through his return to office. For example, in his second inaugural address, Trump declared: “From this day forward, our country will flourish and be respected again all over the world. We will be the envy of every nation, and we will not allow ourselves to be taken advantage of any longer.” The administration’s 2025 National Security Strategy echoes this theme, asserting that “America is strong and respected again—and because of that, we are making peace all over the world” while highlighting America’s “unmatched ‘soft power’ and cultural influence” as the foundation of its global leadership.

This section evaluates these claims. Drawing on recent global and domestic polling, it assesses whether perceptions of U.S. power, leadership, and influence have in fact improved during the first year of Trump’s second term—and how the United States is now viewed abroad relative to China as an economic and geopolitical leader.

What the polling shows

Evaluating the validity of these claims requires moving beyond official statements to observable indicators of global sentiment. A useful place to begin is with polling on which country the world views as the leading economic power. Recent polling reflects a shift in global sentiment, with confidence in U.S. leadership declining sharply, including among key allies in Asia.

The Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Survey reveals substantial volatility in global perceptions of economic leadership. In 2020, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, views tilted decisively toward China: nine surveyed countries identified China as the world’s leading economic power, compared with only two that named the United States—an assessment likely shaped by perceptions that China managed the pandemic and its economic fallout more effectively. By 2023, sentiment shifted sharply in the opposite direction. Ten countries identified the United States as the leading economic power, five selected China, and six viewed the two as roughly equal, reflecting America’s post-pandemic economic rebound alongside mounting concerns over China’s slowing growth. Yet by early 2025, the trend reversed more sharply: 12 countries identified China as the foremost economic power, eight selected the United States, and four saw them as equal. These swings suggest volatile but unmistakable deterioration in global confidence in U.S. economic leadership during Trump’s first year, with China again viewed as ascendant.

Favorability data across U.S. treaty allies show a striking and uniform deterioration in views of the United States over the past year. In every allied country surveyed—including South Korea, Japan, Australia, France, Germany, and Canada—public opinion has shifted sharply toward more unfavorable views and away from favorable ones. The declines are not marginal: they are double-digit drops in every case.

Taken together, these trajectories demonstrate a broadly synchronized decline in confidence in U.S. leadership among the very countries the administration identifies as essential partners in competing with China. The fact that these shifts occurred in close U.S. allies—and in a single year—underscores the political costs of the administration’s approach for America’s standing and influence abroad.

In contrast, views of China remain overwhelmingly negative across all surveyed U.S. allies—but the year-to-year movement runs in the opposite direction of the U.S. trends. While China continues to be viewed unfavorably by large majorities in South Korea, Japan, Australia, France, Germany, and Canada, several countries recorded small but notable improvements in positive sentiment toward China between 2024 and 2025.

These changes do not indicate a surge of goodwill toward Beijing. But they point to an emerging and consequential perception dynamic: although U.S. allies remain far warier of China than the United States overall, their views of the United States are deteriorating much faster than their views of China. This asymmetry raises questions about the administration’s claim that America is “respected again” and complicates Washington’s ability to coordinate with allies and partners to advance U.S. security and economic interests.

At the same time, confidence in America’s positive global role has deteriorated across nearly every region. Ipsos polling conducted between October 2024 and April 2025 documents a systemic global decline in the share of respondents who believe the United States will have a positive influence on world affairs. Again, the erosion is especially severe among treaty allies. The breadth of this downturn suggests a widespread recalibration of how U.S. leadership itself is perceived.

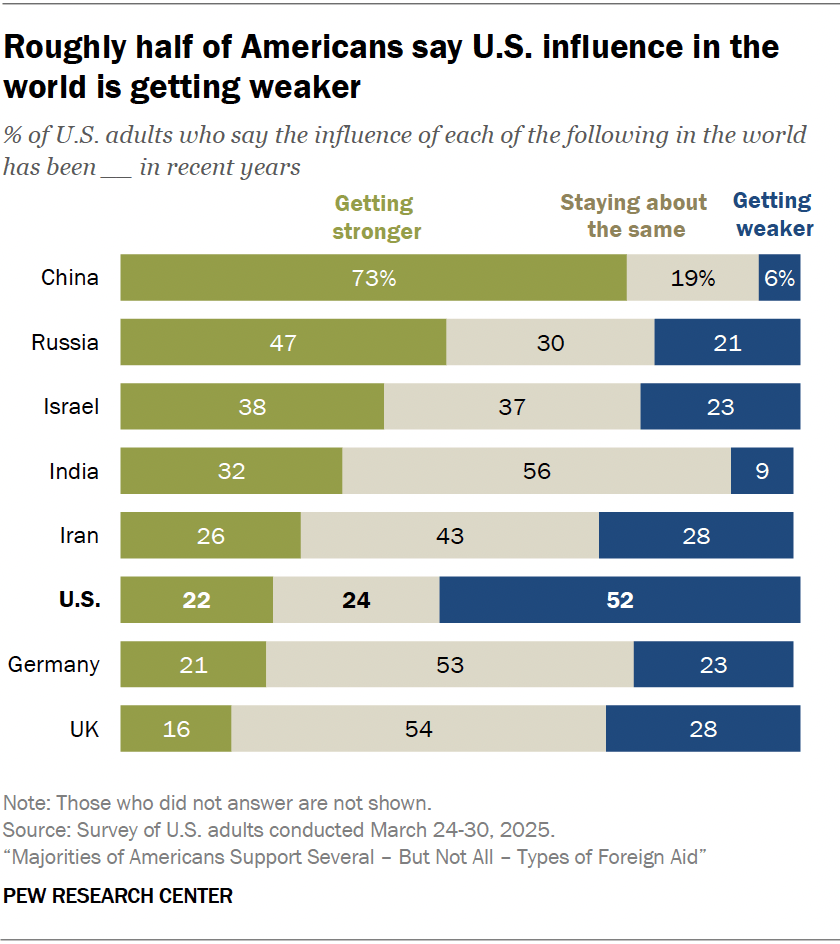

Domestic public opinion reinforces these international trends. A March 2025 Pew survey found that 73% of Americans believe China’s influence in the world is getting stronger, while 52% believe U.S. influence is getting weaker. Notably, the United States fares worse on this metric than several other major powers, including Russia, Israel, and India—indicating that perceptions of relative decline in American influence are now prevalent not only abroad but also within the U.S. public itself. Similarly, a YouGov poll, sampling 3,380 U.S. adults in September 2025, found that 51% of respondents disagreed with Trump’s statement that “America is respected again like it has never been respected before.”

Together, these data sharply complicate the Trump administration’s narrative of renewed American prestige. Instead, both international and domestic audiences increasingly perceive U.S. leadership and economic influence in decline, while China’s is rising. Particularly concerning are allied perceptions of the United States. These perception shifts carry direct strategic consequences for U.S. China policy. America’s ability to diversify supply chains, build markets for its products, garner support for its preferred standards, and forge military partnerships is weakened by diminishing perceptions of American leadership. Declining confidence in U.S. leadership weakens Washington’s ability to coordinate these multilateral responses and reduces the effectiveness of pressure on Beijing. Rather than demonstrating a broad restoration of American respect, the first year of the administration’s second term reveals a widening gap between rhetorical claims of renewed dominance and the international legitimacy required to sustain long-term strategic competition with China.

Conclusion

While Trump declined to label China as the “pacing challenge” or “revisionist power” in his second term, there is no doubt that China looms large in the Trump administration’s economic and national-security policymaking. Across trade policy, industrial policy, technology, and diplomacy, China continues to serve as the implicit yardstick against which the U.S. government measures American strength and vulnerability. The Trump administration’s diagnosis—that decades of U.S. economic engagement helped enable China’s rise while weakening American industry and autonomy—has translated into a forceful toolkit: sweeping tariffs, investment diplomacy, sharper supply-chain measures, and an AI agenda oriented toward domestic scale and global adoption. The question this report asks is whether those instruments have produced measurable gains relative to China after one year. The evidence suggests that, so far, outcomes remain uneven and often lag behind rhetoric.

On reindustrialization, the administration has elevated manufacturing as a strategic priority and attracted major investment pledges, but key indicators—employment, construction momentum, capacity utilization, industrial production, and industry sentiment—have yet to demonstrate an industrial resurgence. There are gaps between headline foreign and corporate commitments and binding investments. And while there are inherent time lags in industrial shifts, policy uncertainty, tariff volatility, and cost pressures continue to discourage long-term capital expenditure. The United States has not yet shown evidence of narrowing the manufacturing gap with China.

On AI, the United States retains frontier advantages in compute, chip design, and platform ecosystems, but sustaining them is increasingly conditional. Reversals in export controls inject uncertainty and undermine credibility, while infrastructure and energy constraints pose additional challenges. Talent advantages are eroding amid immigration constraints and pipeline concerns, just as China strengthens its self-sustaining capacity. The United States’ international diffusion efforts face headwinds from uneasy trade relationships as well as competition with China’s bundled, state-backed offerings.

On strategic dependencies, the rare earth shocks of 2025 underscore the scale of U.S. exposure to Chinese-controlled chokepoints—and how quickly Beijing can exploit them. The administration’s agenda responds to a real vulnerability, but structural constraints—downstream bottlenecks, China’s price-setting power, and domestic permitting challenges—resist short political timelines. Reducing dependence requires sustained policy continuity, not episodic dealmaking.

Finally, on the question of restoring America’s standing, the polling summarized here complicates the administration’s core narrative. The erosion of allied and global favorability is not merely reputational; it carries tangible strategic costs. Diminished confidence in U.S. leadership weakens Washington’s ability to mobilize partners around the very objectives the administration prioritizes—attracting investment and talent to support reindustrialization, maintaining an edge in the global AI race, and coordinating collective resilience against Chinese strategic choke points.

In conclusion, the Trump administration’s first year performance reveals a recurring pattern: pressure campaigns, headline deals, and executive actions aimed at enhancing U.S. competitiveness vis-à-vis China have outpaced measurable evidence of durable gains. Achieving the Trump administration’s stated objectives will ultimately depend on policy consistency, credible implementation, and the confidence of partners.

If the administration’s “Make America Great Again” claims are to be validated by outcomes rather than announcements, follow-through in the second year will be decisive. That will require stabilizing the policy environment to unlock long-horizon investment; engaging in the downstream work needed to reduce strategic dependencies; sustaining AI leadership through strategically designed policies on export controls, infrastructure, energy, and talent; and repairing America’s global image so that foreign counterparts are willing and able to partner with the United States in advancing shared objectives.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors would like to thank Adam Lammon for editing and Rachel Slattery for layout.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).