The assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri in a massive car bomb explosion on February 14, 2005 has unleashed a series of fundamental political changes. The Syrian army and intelligence services, which have been in Lebanon since June 1976, have left. A country that experienced fifteen years of civil war followed by fifteen years of Syrian domination now has a real chance of sovereignty and independence. A nation divided among several religious communities has united in an unprecedented outpouring in favor of independence and democratization. A population cowed by years of militia rule, succeeded by years of foreign military intimidation, has found its strength and voice in massive demonstrations that reverberated around the world.

Yet for all the positive developments, Lebanon still faces many serious challenges. Caught in the middle of a showdown between the United States and Syria, Lebanon hopes to reap the benefits of Syria’s retreat but without paying the costs that might arise. Bereft of Rafiq Hariri, a larger-than-life prime minister who had led most postwar governments and masterminded economic reconstruction and revival, Lebanon is searching for new political leadership. Saddled with a substantial national debt burden, equivalent to around 180 per cent of its gross domestic product, Lebanon is struggling to avoid renewed economic collapse and social chaos. Having disarmed most militias after the end of the Lebanese war in 1990, Lebanon still has to negotiate the disarmament of Hizballah (Party of God, the main Shi’ite Islamist group), and of Palestinian groups based in the refugee camps.

The crisis touched off by the Hariri assassination, and culminating in Syria’s withdrawal, was the result of changes in international attitudes toward Lebanon and in domestic Lebanese political dynamics that have been building for several years. To capitalize on these changes, Lebanon will need wise and moderate leadership, a unified vision for domestic political and economic development, and targeted support from the international community. If these can be achieved, and the challenges overcome, Lebanon could yet achieve its potential—renewed after a long hiatus—to stand as a regional example of democracy, prosperity, and coexistence in the Middle East.

Six Months that Changed the Country

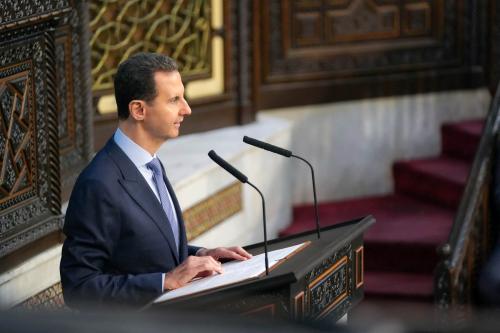

Two fundamental changes several years ago provided the underlying conditions for change in Lebanon. The first came with the death in June 2000 of Syrian president Hafiz al-Asad and his replacement by his less-gifted son Bashar. The second was September 11 and the profound shift that it has brought about in U.S. foreign policy, particularly toward the Arab and Islamic world. The combination of the two meant that when September 11 propelled the United States into the internal politics of the Middle East, it would not be met by a wise and prudent leader in Damascus, a politician capable of absorbing the new U.S. dynamic and avoiding a losing confrontation with it.

The immediate cause of the recent dramatic changes began in the summer of 2002. Prime Minister Hariri had dominated the political scene in Lebanon since first assuming office in 1992. The Syrians initially had mixed feelings about him. He promised economic and social stability for a country that they sought to control, and his appointment, with their approval in 1992, had gained them credit with the Saudis, the Americans, and the French. On the other hand, as Hariri accrued power, the Syrians increasingly saw him as an independent-minded Sunni leader whom they could not control as they had most other Lebanese politicians. Moreover, Hariri’s success could project indirectly into Syria and tantalize the ambitions of that country’s Sunni majority that had been suppressed for more than thirty years by the ruling Alawite minority.

In 1998, the Syrians supported the army commander, General Emile Lahoud—as per tradition, a Maronite Christian—to assume the presidency. Thus began years of political confrontation and deadlock between the president and the prime minister that stalled decision-making and economic recovery. The event that precipitated the current upheaval was the Syrian decision in August 2004, with Lahoud’s term in office coming to an end, to prevail upon the pliant Lebanese parliament to amend the constitution and extend the president’s term for another three years. Using threats and coercion, the Syrians even forced Hariri to move the amendment in the cabinet and vote for it in parliament.

International opposition to Syrian domination of Lebanon, led by France and the United States, had already been growing. The extension of President Lahoud’s term led to a countermove by France and the United States that produced UN Security Council Resolution 1559 (UNSCR 1559) in September 2004, which called for an immediate and total withdrawal of foreign forces—meaning the Syrian military—as well as the disarming of militias, such as Hizballah, and the restoration of full Lebanese sovereignty.

From this moment on, the confrontation between Syria and the West became increasingly overt. The Syrians reacted angrily to UNSCR 1559; they accused Hariri of being behind it, and pressed their allies in Lebanon to denounce the resolution as an illegitimate interference in consensual affairs between Lebanon and Syria. One indication of the escalating tensions was the attempted assassination of parliamentary deputy Marwan Hamadeh in early October 2004 in a car bomb attack; Hamadeh was a close ally both of Hariri and the Druze leader Walid Junblatt, who had also thrown his political weight behind the demand for a Syrian withdrawal. Hamadeh miraculously survived the attack, but the event signaled a showdown and unleashed long pent-up frustrations. The attack on Hamadeh helped crystallize the emerging anti-Syrian coalition among leading opposition politicians. The assassination of Rafiq Hariri on February 14, 2005, came just as these battle lines were becoming clear.

The Lebanese population reacted to Hariri’s murder with a cathartic outpouring of grief and unity. After Hariri’s assassination, the Syrians’ position in Lebanon was no longer tenable. While they had already had a difficult time controlling elements of the Christian opposition, now they also lost control of the Sunni and Druze communities. The anti-Syrian demonstration in Beirut on March 14, 2005 brought 1.2 million people onto the streets, almost a third of the country’s population.

Only the large Shi’ite community stayed out of the oppositionist fanfare and close to the Syrians. Among the Shi’a, Hizballah was opposed to UNSCR 1559 because it aimed to disarm it; and the Amal movement was opposed to the resolution because their leader, the speaker of parliament, Nabih Berri, derived most of his political power from Syria and was likely to lose it if the Syrians left. In addition, the Shi’a had always been somewhat wary of resurgent Sunni power in the country, led by Hariri, and hence reacted differently to the assassination. A pro-Syrian demonstration organized by Hizballah on March 7, 2005 brought out about half a million people.

A unique combination of popular, international, and Arab pressures has now forced Syria to undertake a military and intelligence withdrawal from Lebanon. Syria has accepted UNSCR 1559 and accepted that—for the time being, at least—it must cease its direct interference in Lebanese affairs. There is a growing sense in Syria that the regime has overplayed its hand and committed several strategic mistakes that have brought the threat of confrontation with the United States to its doorstep. The Syrian regime hopes that by pulling out of Lebanon, it will be able to gain international goodwill. However, while the battle yesterday was for domination of Lebanon, the real question today regards the future of the Asad regime itself.

Whither Lebanon?

Lebanon today is in the midst of decisive parliamentary elections; however, there has been great discord over the election law and over electoral alliances. Before the assassination of Hariri, the government at the time proposed an election law featuring small electoral districts; this was favored by the Christian opposition. However, this law was never approved by parliament, and attempts to pass it later failed. Consequently, the country had to fall back on the 2000 election law, which features large districts. These large districts were favored by Amal and Hizballah. As it turned out, the Hariri bloc, Junblatt, and some members of the Christian opposition also found them useful. The problem with these large districts is that the results of the election are determined more by the formation of coalition lists than by voter choice; once a strong list has been assembled, it generally will sweep all the seats in that particular district. The continuation of this election law, which had been drawn up under Syrian patronage in 2000, was seen among the general public as a negative first step in newly independent Lebanon, and as an attempt by the political class to hang together and preserve its interests in the face of potential democratic change.

Also, the turbulent and short election season has mixed up political alliances in the country. The opposition that faced the Syrians included the Hariri bloc (now led by his second son and political successor, Saadeddine), Junblatt, several Christian parties and leaders, as well as the former exile General Michel Aoun, and a number of leftist parties. During the election season, Muslim-Christian unity—which had been greatly cemented in the demonstrations leading up to March 14, 2005—was shaken by accusations made by the Maronite Patriarch, Nasrallah Sfeir, that Muslim leaders were trying to hand-pick Christian candidates. Opposition unity also suffered under suspicions that, while all the opposition leaders publicly supported the small-district election law, many of them secretly favored the continuation of the old large-district law. Finally, unity was threatened by disagreements between Aoun, who returned to Lebanon in early May 2005 after fifteen years in exile, and other members of the opposition who were wary of giving Aoun too much room or too many seats in the new parliament.

Nevertheless, the elections are taking place over four Sundays, between May 29 and June 19, 2005. They will bring to office an overwhelming majority of deputies opposed to Syrian influence. The main blocs in parliament will be, in order of size, a Hariri bloc, a Junblatt bloc, a Hizballah bloc, an Amal bloc, and blocs for Aoun, the Lebanese Forces (the former Christian militia), and the Christian Lebanese Kata’ib Party. Although Amal and Hizballah were on the pro-Syrian side in the recent standoff, they have cooperated with the Hariri and Junblatt blocs to exploit the large-district system during the elections. Exactly what alliances will emerge among the various blocs after the elections are over has yet to be seen.

Among the main issues immediately facing the new parliament is whether to abrogate the final two years of President Lahoud’s term and elect a new president. With a two-thirds majority in parliament, this can be done by amending the constitution to cancel the extension that was granted him in 2004. The issue then would be whom to elect to the presidency. There are several candidates for this position, including Aoun and various other Maronite politicians, some allied with Saadeddine Hariri and other members of the Christian opposition coalition known as the “Qornet Shehwan Gathering” (named after the town where its initial meetings were held). A second key issue is whether to reelect Amal leader Nabih Berri as speaker of parliament or to choose someone else. There is widespread sentiment that Berri, who has served throughout the postwar period, is too embroiled in corruption and has not developed parliament into an effective and democratic institution.

While the contests for the posts of president and speaker of parliament are fairly open, the race for the prime ministership is much more restricted. The prime minister’s post had been dominated by Rafiq Hariri. Consequently, the Hariri family and its large political following will now have the primary say in who occupies this post. Saadeddine Hariri may choose to become prime minister, or he might name someone from the Hariri bloc to occupy the post.

In any case, much will depend on successful leadership and cooperation among the new president, the new prime minister, and the (new or old) speaker of parliament. There is much to be done in Lebanon to reinforce the sovereignty of the state, ensure the dominance of the Lebanese army after the Syrian withdrawal, restructure Lebanon’s international relations, develop Lebanon’s democracy, implement necessary internal reforms, and re-launch the Lebanese economy. The country will also be awaiting the results of the International Investigative Commission set up by UNSCR 1595 to find out the truth about Hariri’s assassination. If the investigation were to implicate those high up in both Lebanese and Syrian political and security structures, there might be dramatic and unpredictable consequences.

Immediate attention, as well, must be paid to the issue of Hizballah and its potential disarmament, as required in UNSCR 1559, alongside the question of what to do about the armed Palestinian groups in the refugee camps. All this must be done in an environment of continued tension and uncertainty with regard to US-Syrian tensions, US-Iranian relations, and the Arab-Israeli conflict. Lebanon has been given a great opportunity by regaining its independence and sovereignty. It has the potential to make great strides toward building a truly democratic, free, and prosperous society. But, as a small and still somewhat segmented country in a turbulent environment, its path forward weaves through a minefield.

What has Changed?

The international environment has changed dramatically. Syrian control of Lebanon since 1990 was indirectly condoned by the United States, which had needed Syria during the construction of its Arab coalition against Iraq in the first Gulf War. France, Europe, and most of the Arab world went along with this arrangement as the most handy solution to the seemingly endless Lebanese war. After the death of Hafiz al-Asad, after September 11, and most recently after the assassination of Rafiq Hariri, Syria has lost the regional and international acceptance for its role in Lebanon that it once enjoyed, while Lebanon has reemerged as the subject of intense Arab, European, and American interest. Whereas Lebanon in 1990 was an open wound that somebody needed to patch up, Lebanon in 2005 represents something quite different to the international community. For the Bush administration, the independence and success of Lebanon is now seen as an important feather in the cap of President George W. Bush’s freedom and democratization vision for the Middle East; for France, liberating Lebanon brings back a historic friend of France in the eastern Mediterranean. For Saudi Arabia, the other Gulf states, Egypt, Jordan, and other Sunni Arab countries, pushing the Alawite regime out of Lebanon is partly a way to retaliate for the assassination of Hariri, who after all was also a Sunni and a Saudi citizen, and partly a way to counterbalance the eclipse of Sunni power by Shi’ite power in Iraq. Lebanon, for the time being, has a dramatically different value and meaning in regional and international affairs than it did only a short time ago.

International changes have also directly affected Hizballah. Without Syrian political and military cover, Hizballah’s supply lines of money and materiel from Iran have been seriously jeopardized. Also, since the Israeli withdrawal from south Lebanon in May 2000, Hizballah has been having an increasingly hard time justifying its continued possession of weapons to the wider Lebanese public. The head of Hizballah, Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah, has been very active over the past weeks in reaching out to all sides in the Lebanese political scene and trying to find a path and a place for Hizballah in the new Lebanon. Most Lebanese are still respectful and friendly to Hizballah, as they credit it with pushing the Israelis out of Lebanon and not abusing its power as other militias had done in the past. Hizballah has remained a professional group that has not become openly associated with corruption, smuggling, or mafia-style behavior, as most wartime militias did. Most Lebanese, therefore, make a distinction between the two main clauses of UNSCR 1559: they wholeheartedly supported an immediate Syrian withdrawal under international pressure; but they prefer that the disarming of Hizballah be done in a cooperative and gradual manner, in full consultation with Hizballah and as part of a Lebanese process—not a process imposed or forced by the United States or the United Nations.

There are two issues closely related to the Hizballah disarmament issue. The first is that most Shi’a in the south remember that the Palestine Liberation Organization and other armed Palestinian groups largely ruled the area between the late 1960s and 1982. They fear a return to such a situation if Hizballah precipitously disarms without strong military and political guarantees against a re-deployment of Palestinian—predominantly Sunni—armed groups from the camps into the south. Second, many Shi’a as well as other Lebanese believe that Hizballah, having pushed the Israelis out of Lebanon, is the main deterrent against any future Israeli attacks or invasions of south Lebanon. They fear that if Hizballah is disarmed, the Lebanese state and army will not be willing or able to retaliate or inflict any noticeable deterrent punishment on Israel. Nevertheless, Hizballah is facing dramatic new conditions in the post-Syrian era. There will have to be intensive regional and international efforts to achieve a gradual disarmament of Hizballah, along with a significant change in the situation of armed groups in the Palestinian camps, as well as some form of progress on the Arab-Israeli peace process.

Rafiq Hariri, the main engine of the postwar period, is gone. Lebanon has lost a powerful leader. It must now fall back on its republican past and find ways to supplant his personal role with a more collective form of cooperative leadership.

The political class is going through a period of significant flux. The politicians that constitute that class today are the result of fifteen years of war followed by fifteen years of Syrian control. Many will soon disappear from the political scene. Others will have to quickly adapt to the new realities, and some newcomers will emerge. All politicians will have to move away from the Syrian-brokered habits of the past and find ways to build national coalitions without help or obstruction from abroad.

Above all, the awakening and empowerment of the people has dramatically changed the political paradigm. Most of the Lebanese population had been beaten into fear, disillusionment, and passivity by the fifteen years of war and fifteen years of foreign domination. However, the assassination of Hariri and the international community’s stand against the Syrian presence triggered an explosion of emotion and willpower among most Lebanese. The demonstration on March 14, 2005 brought out a third of the entire population of the country. Such a high rate of public participation occurs only rarely in history. The public has emerged as a potent force in political life, and the political class will have to take account of its demands in the months and years to come.

What has Remained the Same?

Change in Lebanon is taking place within the context of constitutional and institutional continuity. This contrasts with Iraq, where a shift in external power brought about a fundamental change in the regime, state institutions, and society. The Lebanese constitution has been in force since its writing in 1926, with only minor suspensions under the French during World War II. Fundamental amendments were made only twice: in 1943 to eliminate the clauses relating to the French Mandate, and in 1990 to introduce changes in the communal power-sharing formula agreed upon in the war-ending Ta’if Agreement of 1989. There have been regular parliamentary elections since 1927, except during the Lebanese War of 1975-1990, and fairly orderly transfers of executive power, despite the extension of the president’s term twice in the postwar period, in 1995 and 2004. In addition, the military and civilian institutions of the state have existed and developed since the French Mandate era—even though their reach was dramatically circumscribed during the Lebanese War. Lebanon has had the institutions and political culture of statehood and cooperative, electoral-based government for many decades. Although Lebanon faces many changes, it has not embarked on some brand new political adventure or experiment, but rather a process of reinforcing existing institutions and behavior patterns.

Lebanon’s strong and vibrant civil society helped bring the country through the fifteen years of war without the dramatic collapse that we have seen in Iraq, Afghanistan, Sudan, and elsewhere. Lebanon has never been a totalitarian state, unlike many other states in the region. As a result, its civil society developed steadily throughout the twentieth century. Although Lebanese civil society is a mix of traditional, communally based associations and more modern and democratically oriented civic groups, both types of associations and institutions provide a rich web of intermediate institutions, organizations and networks that provide strength and durability to the society, even at times when the state is in great flux or has all but disappeared. This is one of the sources of Lebanon’s strength and survival even in the most difficult of times.

The Lebanese army remains a source of continuity and stability. This army is still the center of much national identification and pride. Although it suffered divisions during the war, the army was reunited after the war, and since almost all families have one or more of their extended family members in the army, it is a national institution with which most people directly identify. While the political class and the intelligence services were deeply involved in Syria’s political and security manipulation of Lebanon during the past fifteen years, the army was instead accorded standard military and security-keeping functions. During the recent confrontations between the government and the opposition, the army quietly took a moderate position, not openly disobeying government orders, avoiding clashes with opposition demonstrators, and often looking the other way to facilitate their gatherings. Although the army is no match for any of its neighbors, it is a strong force in terms of internal security. It is the largest and strongest institution in the state and society, and is functioning as a pillar of stability in the current period.

Although most Lebanese are delighted to be rid of the Syrian military and intelligence presence, they still feel it is in Lebanon’s interest to maintain close relations with Syria. They understand that there are common interests with Syria; but more importantly, they realize that if they drift into policies or alliances that are hostile to Syria they are likely to pay a very high price. Mainly this means that Lebanese are largely agreed that it would be unwise to pursue peace talks with Israel, if Syria is not going along as well. After the Israeli withdrawal of 2000, Lebanon does not have any major territorial disagreements with Israel except the minor issue of the Sheba’a Farms on the Lebanese, Syrian, Israeli border. Syria, on the other hand has the entire Golan Heights to reclaim. Lebanon cannot afford to move ahead with separate peace talks with Israel and risk seriously angering Syria. Indeed, most Lebanese feel that, given the number of times other Arab countries have accused them of treason, they are happy to be among the last in the line of Arab countries signing peace agreements with Israel.

Prospects for Stability, Democracy, Good Governance, and Prosperity

Lebanon is currently enjoying a high level of internal unity. With the withdrawal of all foreign forces, Lebanon now has the opportunity to be sovereign in all its territory. A coalition of Arab and Western countries is keen to help Lebanon reinforce its sovereignty and take firm steps toward rebuilding its democracy and economy. The reasons for the outbreak of war in 1975 are no longer present, and the country has most of the institutions that would enable it to develop a well-functioning state, democracy, and economy. Lebanon is facing a historic opportunity to move forward. For the first time in many years, the future of Lebanon is in Lebanese hands again.

The challenge now largely falls on the political leadership that will take the lead in the coming months. Will they have the vision and skills to reinforce national unity, develop state and democratic institutions, institute necessary reforms, and kick-start the economy? Will the population and civil society maintain the pressure on the political class to deliver the necessary unity, reform, and change? Or will Lebanon fall victim to political bickering and division, as it has on several occasions in its recent history, and lose this historic opportunity?

It is difficult to predict the answers to these key questions, as the country moves into decisive parliamentary elections followed by decisive elections for the presidency, the prime ministry, and perhaps the speakership of parliament. The leaders of tomorrow’s Lebanon, most of whom are in the opposition today, will have to avoid falling into old patterns of division and disagreement. They will have to make a concerted effort to develop a shared program of reforms and policy initiatives to take advantage of the power shift that is taking place. They must do more than just kick the Syrians and their allies out of power; they must also bring meaningful and useful change to the country.

Two main potential sources of instability in the coming period are Syria and south Lebanon. If U.S.-Syrian tensions continue to escalate and turn into pressures for regime change, a cornered Syria might lash out in Lebanon as well as elsewhere. Lebanon could scarcely guard against the repercussions of Syrian efforts to destabilize the country. If the Syrian regime is overthrown, Lebanon would also bear the consequences. It is conceivable that a change of Syrian regime might be achieved through a quick coup that does not lead to a breakdown of order; but it is perhaps more likely that it might result in a breakdown of law and order and near civil war, along the Iraqi model. This would be a dangerous, if not disastrous, scenario for Lebanon, given the proximity and interconnectedness of the two countries.

As for south Lebanon, the new Lebanese government will have to find a way to deal with Hizballah, the armed Palestinian groups, and Israel. UNSCR 1559 calls for the disarming of all non-government armed groups in Lebanon, which includes Hizballah and the Palestinian armed groups. This can only be achieved through intensive and delicate negotiations involving Hizballah and the Palestinian leadership, as well as Iran, the United States, and indirectly, Israel.

If these two risk areas do not generate major security eruptions, Lebanon is likely to move in a positive direction. The removal of Syrian domination is likely to lead, almost by definition, to increased sovereignty and better democracy. This in itself is likely to lead to a significant improvement in governance. There is much that needs to be done to enhance the benefits of this opportunity, but the general direction of change in this regard will probably be positive, even without major visionary leadership.

On the economic level, although Lebanon will continue to struggle with a massive debt burden, these changes in sovereignty, freedom, and governance can only have a positive effect on Lebanese, Arab, and foreign investment in the country and on the prospects for economic growth. Even in the difficult circumstances of the past, Lebanon achieved stunning strides in rebuilding the country after the war and in re-establishing a place for itself as an emerging hub of regional tourism and services. If this could be achieved under Syrian occupation, it is likely that much more can be done without it, even if the recovery’s main architect, Rafiq Hariri, is no longer present.

The Role of the United States and the International Community

When all is said and done, the fact is that it was mainly the United States that pushed Syria out of Lebanon. Although Hariri may have been behind the idea of UNSCR 1559, and might have persuaded French President Jacques Chirac to engineer it, the fact is that had Chirac not convinced President Bush, and had the Bush administration not provided the power to back it up, Syria would have been able to ignore the resolution.

While Lebanese are grateful to the United States, France, the United Nations, Saudi Arabia, and the international community for prevailing on Syria to get out of Lebanon, they are very concerned that Lebanon might break loose of one foreign domination only to end up under another. The examples of U.S.-managed governments in Afghanistan and Iraq are neither appealing nor successful. Lebanon is a complex and delicate country. The United States should be careful not to overplay its hand, and not to interpret the ease with which Syria left the country as equivalent to the ease with which the United States could get directly involved in the country.

The United States, as well as Europe, the United Nations, and the rest of the international and Arab community, should follow up what was, in effect, the liberation of Lebanon by encouraging Lebanon to reconstitute a strong, sovereign, and democratic state. The international community should help this new state rebuild its institutions and restart its struggling economy. Lebanon has the institutions and individuals to carry out these tasks, and the international community can successfully support an indigenous process. With regard to Hizballah, which is the main U.S.- and UN-related demand of international concern within Lebanon, this should be done gradually and diplomatically. Lebanese understand that this issue cannot be postponed indefinitely, but the international community must understand that it cannot be achieved overnight and that it is connected to issues relating to the Palestinians, Israelis, and Iranians. It must be said that both U.S. and UN diplomats have been very balanced in their recent approach to these thorny issues, and have exhibited understanding of their complexities.

It would seem that after decades of division, domination, and distress, Lebanon might finally be on the path to sovereignty, unity, democracy, and development. The country has benefited greatly from the support of the international community. Further support should see Lebanon consolidate the historic opportunity that is before it and move towards a better future. Lebanon can then recapture its role as an example of democracy, prosperity, and religious coexistence that is of great importance not only within the Arab and Islamic worlds, but within the international community as well.

Paul Salem is a writer and political analyst based in Lebanon. He is the author of Bitter Legacy: Ideology and Politics in the Arab World (1994), and the editor of Conflict Resolution in the Arab World (1997). He was a contributor to the UNDP Arab Human Development Report and the World Bank’s recent study on governance in the Arab world. He is the founder and former director (1989-1999) of the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies, Lebanon’s leading policy think tank. He is currently running for parliament as a Greek Orthodox candidate in the Koura district of north Lebanon.

Commentary

Lebanon at the Crossroads: Rebuilding An Arab Democracy

May 31, 2005