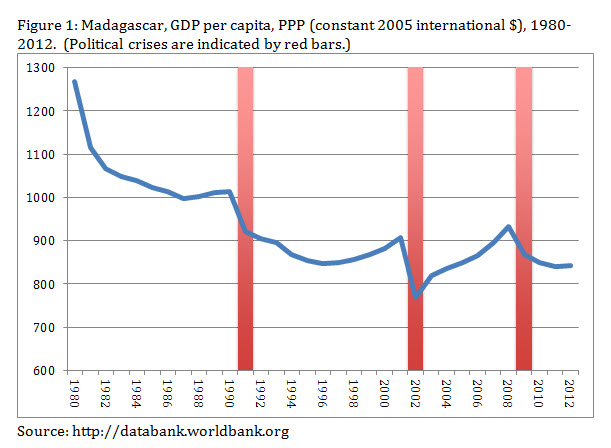

On December 20, 2013, voters in Madagascar will go to the polls to elect a new president. Several priority items are waiting for the winner but one of them—the “Madagascar Cycle,” the phenomenon when, just as a growth is about to take off, a political crisis occurs—has been a constant challenge to policymakers in the recent history of this island country. Indeed, all past episodes of rapid growth in Madagascar have been short-lived and never sustained. Invariably, those growth spurts were stopped by a political crisis, each time sending the economy in a tailspin (see Figure 1 below).

As a result, policymakers have not been able to reverse Madagascar’s long-term economic decline. For the last three decades, the GDP per capita has declined by an annual average of 1.2 percent—shrinking from $1268 in 1980 to $843 in 2012 in PPP (constant 2005 international $) terms. The World Bank estimates that more than 92 percent of the population lives under $2 a day and poverty has sharply increased. Therein lies the key driver of the “Madagascar Cycle.”

From a political economy perspective, the “Madagascar Cycle” is a case study of what happens when growth is not inclusive, or, to use newer jargon, when prosperity is not shared. Sure, the economy experienced growth spurts. Sure, allthe macroeconomic indicators improved. But, unfortunately, some parts of society—some regions, some professions, some sectors, some business interests, and the list goes on—were left out and did not partake in the economic successes. As the economy continued to grow, so did the frustration of these excluded groups. And with frustration grew resentment. Add to the mix a dash of weak institutions and a pinch of opportunistic disgruntled politicians, and you have all the ingredients for a “Madagascar Cycle”—each time the economy seems poised to take off, political unrest erupts! The Malagasy propensity for centralized economic and political power tends to exacerbate this already explosive cocktail.

The new president of Madagascar and his government will obviously need to take on the task of stabilizing and jump-starting an economy battered by an almost 5-year-old political crisis (combined with a number of natural disasters). He will need to restore mutual trust and respect between Malagasy citizens and its various government institutions. He will need to deal with the growing insecurity problems. He will need to reassure investors, donors and other stakeholders that his administration is the real deal.

Those are the less difficult tasks. The Malagasy economy is very well endowed and has shown the potential for high economic growth. Malagasy policymakers and their advisers have demonstrated that they are capable of generating economic growth. There is no doubt about that. But now is the time for them to step up to the plate and figure out how to sustain such growth. Will they be capable of making economic growth more inclusive? Can they generate prosperity that will be broadly shared? This will not be an easy exercise. But if the new administration is serious about the welfare of the 20 million odd Malagasy citizens, one top priority should be to understand and deal once and for all with the drivers of this unfortunate cycle. Let’s root for them!

Soamiely Andriamananjara is a senior economist at the World Bank Institute. These are his personal perspectives and do not necessarily reflect those of the World Bank.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

It’s Time to Break the “Madagascar Cycle”

November 20, 2013