Editor’s note: Israelis will go to the polls on March 17 to elect the 20th Knesset, Israel’s parliament, which will then form a new government to replace Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s current one (he hopes to head the next government as well.) We are following the run-up to the elections

in a series here on Markaz

, the blog of the Brookings Center for Middle East Policy.

In the previous post in this series, I described what I see as the challenges that the Labor Party—Netanyahu’s main opposition—faces in overcoming a longstanding structural advantage the Right-Wing has in Israeli politics. In this post, I look at the current polling numbers to get a sense of who the likely winner might actually be—that is, who is most likely to form the next government in Israel. It is very early in the game, and there are major caveats to be made about making projections based on the data at this stage. I discuss several important caveats at the end of the post.

The rules of the Israeli political game [1] entail that we may not know the identity of the next prime minister even after all of the votes are counted. Identifying the largest faction—the first-past-the-post winner in the U.S. sense—is not nearly enough. In 2009, the “winner” was ostensibly Kadima, then led by Tzipi Livni, which received 28 seats, compared to the Likud’s 27, but Netanyahu was tasked with forming the next government, given that he had wider support within the new Knesset as a whole. The key, as always in Israeli politics, is the arithmetic of coalition building.

The political landscape

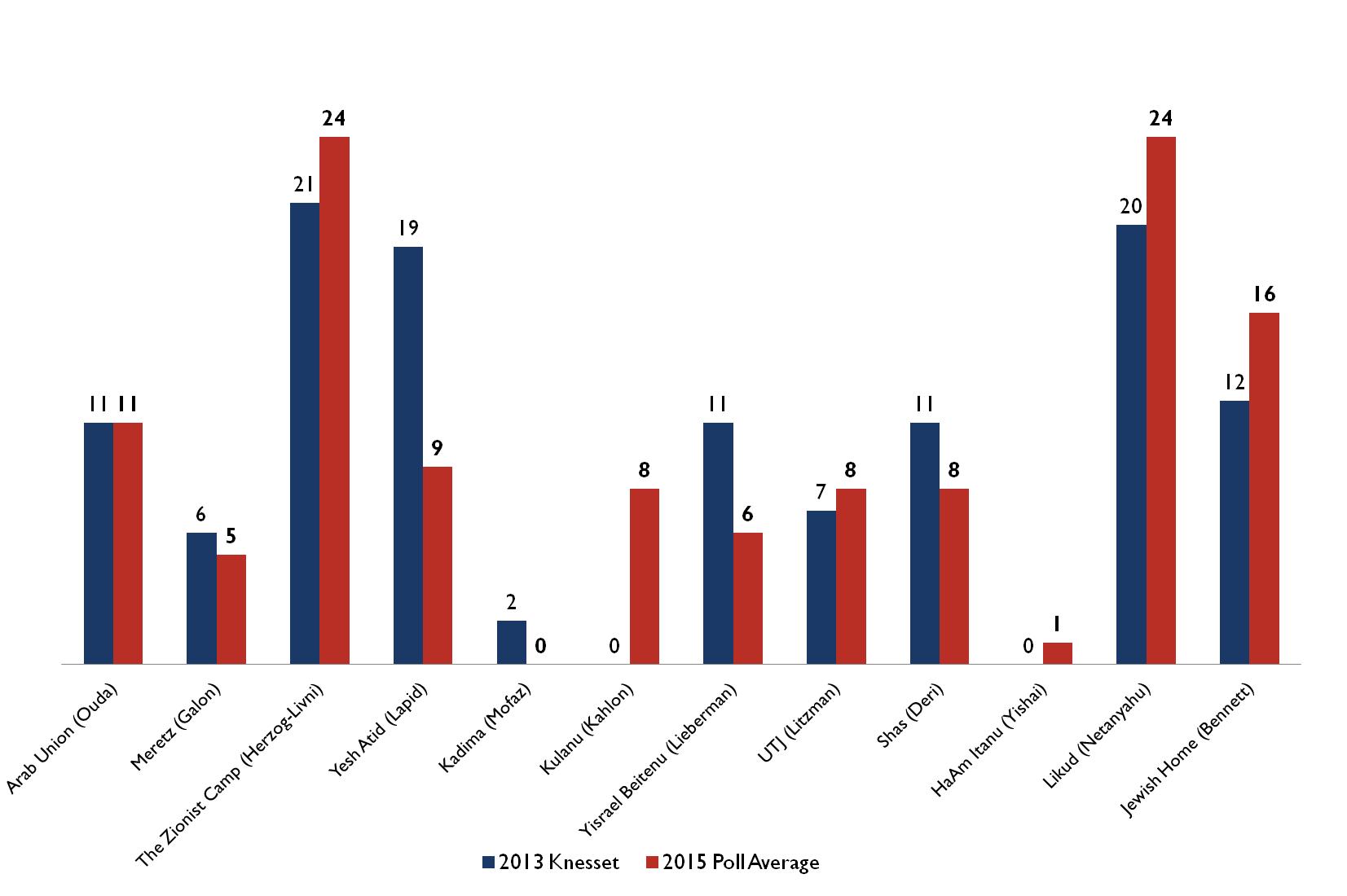

Here’s a first look at the full political spectrum, more or less on a “left” to “right” axis, though the placement is arbitrary at times (Lieberman can be reasonably placed much further to the right, for example, though he has been positioning himself in the center, in some respects, over the past few months).

Figure 1

The 2015 polling number numbers are drawn from a running 3-poll average published by Ha’aretz, as of January 22, 2015, [2] while the 2013 numbers are drawn from the official Knesset website.

(In all these charts I alternate using the names of leaders of parties in some cases, and the names of the parties themselves in others, depending on which is more commonly used. Not completely kosher, but most Israelis don’t keep kosher anyway. [3])

Bibi is not “blocked”

In the fractured Israeli party system evident in Figure 1, and given the longstanding Right-Wing advantage, the first question to ask is: Does the Center-Left bloc have 60 seats (half) to prevent a Right-Wing coalition? The answer to this question, at present, is unequivocal, and has been stable for a long time: No.

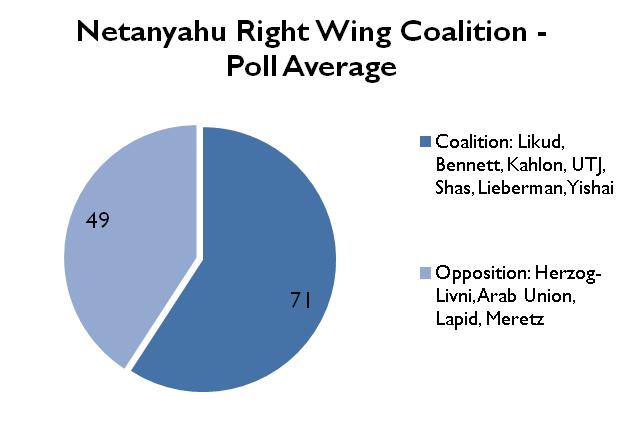

Figure 2

As Figure 2 shows, the anti-Bibi (Netanyahu) bloc, from Lapid leftward, is polling at just below 50 Knesset seats, well below the requisite 60. Recall, furthermore, that Lapid was the major partner in Netanyahu’s last government, meaning that, in normal times, Netanyahu would appear to be the clear frontrunner in this race.

Even without Lapid, a “natural” Netanyahu coalition would have 70 or 71 seats (Yishai’s sole seat, if he did not pass the threshold, would go somewhere else), rendering it a “safe” coalition.

Swing parties may swing

These are not normal times, however. Netanyahu fatigue is such as that the elections have become, to a degree, a referendum on Netanyahu himself. Among the political elite, in particular, most would prefer to replace Netanyahu. Moshe Kahlon, a former Likud minister who left the party last fall amid acrimony with Netanyahu, is clearly positioning himself and his new party Kulanu in the center. Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman, Netanyahu’s old ally, has made no qualms about his newfound centrist perch. The Ultra-Orthodox parties—UTJ and Shas, though not Yishai’s splinter party—have a score to settle with Netanyahu for abandoning them, albeit reluctantly, in favor of forming a secular-Modern Orthodox coalition in the previous Knesset.

Herzog, moreover (and unlike his partner, Livni) has very good relations with his fellow politicians, both within his own party and across the political spectrum. If anyone can form an unorthodox coalition, his camp argues, it is him.

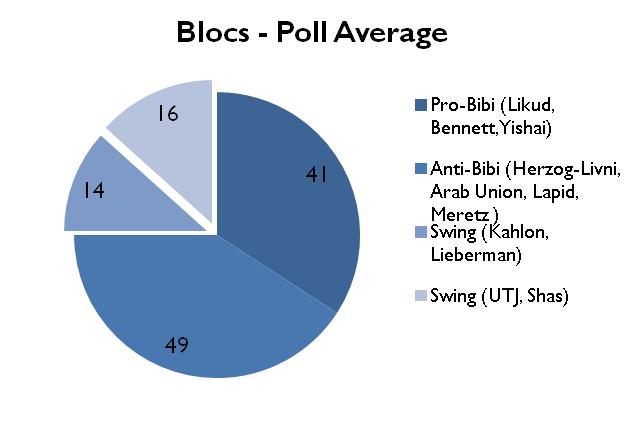

Assuming, therefore, that the swing parties of Kahlon, UTJ, Shas and even Lieberman do not automatically recommend to the Israeli president that Netanyahu be appointed prime minister, Herzog may have a real shot. Here’s what the blocs look like, separating out the swing parties:

Figure 3

Recommending Herzog would be very difficult politically for the swing parties, however. Lieberman’s and the Ultra-Orthodox constituencies are far more hawkish and anti-“left” than their leaders. It may be hard for them to sell to their voters a recommendation for Herzog outright when Netanyahu is available. For Kahlon, the picture is more mixed—some of his voters are probably genuinely centrist—but he himself was a longtime Likud member. Choosing Labor over Likud (or vice versa) is a fundamental breach of loyalty for many diehard supporters of each party.

One option for these parties would be to simply recommend no one to the president, or even to recommend their own party leaders (who have no chance of forming a government). President Ruvi Rivlin (a former Likud member but one who, like many others, has a score to settle with Netanyahu) might then task Herzog with forming a government, at which point the swing parties may join, hoping to dodge the public responsibility of dethroning Netanyahu themselves.

The key: post-election horse trading

The key, therefore, is how fed up these swing parties are with Netanyahu; How much do Lieberman and Kahlon in particular want to dethrone Bibi?

Or, rather, how much political gain do Kahlon and Lieberman, and perhaps the Ultra-Orthodox, see in playing the swing card; how much can they extract, in political terms, from Herzog or from Netanyahu?

The post-election horse trading may be especially ugly this time around.

A Herzog coalition would be very difficult to maintain

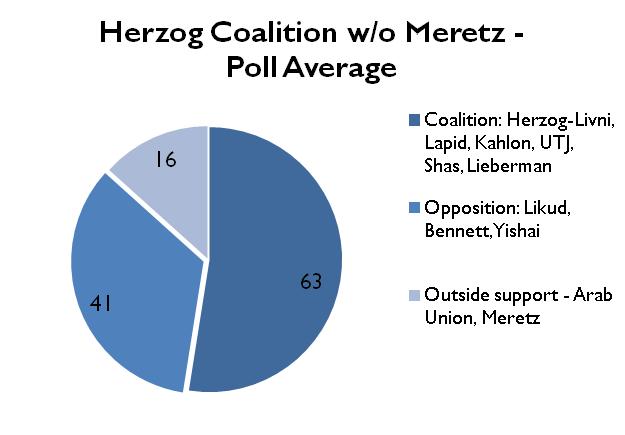

Figure 4

If the numbers hold, and should Herzog be tasked with forming a government despite Netanyahu’s apparent advantage, Herzog would likely need to join forces with a wide range of parties: Kahlon’s Kulanu, Lieberman’s Yisrael Beitenu, the Ultra-Orthodox UTJ and Shas (but not Yishai), and Lapid’s Yesh Atid. The Arab parties have made clear that they will not join a coalition (nor would they be invited), but they may support the coalition from the outside on some key issues, as they did during the tenure of the Rabin-Peres government of 1992-1996.

Herzog would face three main difficulties in building and maintaining such a coalition: first, the Ultra-Orthodox have stated that they will not join any coalition that included Yair Lapid, the secularist leader responsible for keeping them out of the previous governing coalition, meaning that even the razor-thin coalition depicted above may not be possible. (Without Lapid or the Ultra-Orthodox, there is no coalition to speak of.)

Second, Lieberman and Meretz have each stated that they would not join the same coalition (the coalition above excludes Meretz and places it in the outside-support category.) Herzog could substitute Meretz for Lieberman, but his coalition would still only constitute 62 MKs and he would lose the outside support Meretz would guarantee him on many issues.

Third, assuming Herzog can cobble these parties together, opportunities for coalition crises would abound. Any issue pertaining to the budget could cause a row between the neo-liberal Lapid and Lieberman on the one hand, and the socialist-minded Labor on the other. Any issue of religion-and-state—a major issue in Israeli public life—would cause a crisis between Lapid and the Ultra-Orthodox, even if they did agree to join the same coalition.

This scenario could still happen, even if for only a short period of time. The swing parties may decide to get rid of Netanyahu, in which case even a short-lived Herzog government could suffice to bring about a revolt inside the Likud, after which the coalition may collapse. The swing parties may be offered enough by Herzog to entice them to try such a coalition despite the difficulties. And the numbers may change to make this scenario less difficult.

Crazier things have certainly happened in Israeli politics, but a narrow Herzog coalition would be difficult to build and a nightmare to maintain.

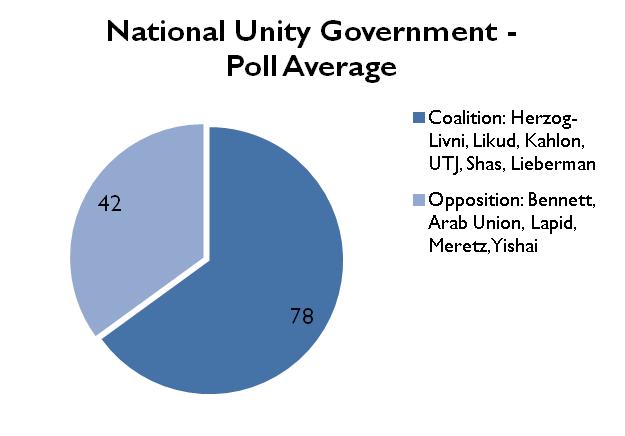

National unity works, sort of

If a Herzog government is difficult to create, and if Netanyahu’s “natural” partners may not go along with him easily, Netanyahu and Herzog may well try and join forces in a national unity government.

For Kahlon and Lieberman, too, this may be the easiest option to sell to their constituencies. Indeed, Lieberman has already endorsed the idea, a longtime favorite of his.

Figure 5

The current numbers suggest that a national unity coalition would be relatively easy to build, numerically. Lapid and Bennett, the winners of the last Knesset’s coalition building, could both be excluded, to the great joy of the Ultra-Orthodox and of many on the left (who would love to have Bennett and his party in the opposition). The main parties could share the spoils relatively easily amongst them and the extractive power of the swing parties would be reduced.

Who then would lead a national unity government as prime minister? If the two parties are of similar size (as in the current polling numbers), tradition from 1984-1988 would suggest a rotation in the prime minister’s office between Netanyahu and Herzog (in 1984-1988 Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Shamir took turns at the helm). If there is a significant disparity between the parties—such that one of them does not need the other to form a government—the other may join as a junior partner (as was the case in 1988-1990 and again, intermittently, in 2001-2002 and in 2005.)[4]

The main difficulty would then be within the two main parties. In the present Likud, there are many MKs who are very nationalist and vehemently opposed to Labor policy and politicians and could scarcely serve under a Prime Minister Herzog. Within Labor, there will be many who will be vehemently opposed to joining a Netanyahu-led government. The socialist-minded politicians I described in the previous post, for example, view Netanyahu not only as a hawk they cannot support but, equally, as a far-right neo-liberal on economic issues. A national unity government would be a hard sell for Herzog in Labor, where many already suspect that he would join a unity government if the possibility presented itself.

A national unity government, in short, is a definite possibility as well. It won’t be easy sailing, however.

So Who Will Win?

With the long list of caveats noted below, the current polling numbers suggest that the winner of the elections may only be determined post-elections. The most likely, and stable, outcome remains a Netanyahu government, assuming he can overcome the “anyone but Bibi” sentiment among his fellow politicians. A Herzog coalition is technically possible, but would be hard to build or maintain, unless the numbers improve for Herzog’s bloc. And a national unity government could work well arithmetically, but could face fierce opposition within the two main parties.

Netanyahu could certainly lose, in other words, but the elections are still his to lose.

————————————————————————————————————————–

Caveats and qualifications:

- It is very early in the game and the final set of parties may change. Party lists are due on January 29th, before which parties may merge, appear, split or withdraw, which would change the landscape considerably. For example:

- There is some talk of a union between Netanyahu’s Likud and Bennett’s Jewish Home.

- Kadima, which I include, is currently running well below the new electoral threshold and may decide to withdraw from the elections or merge with another party if it can (This week, the Zionist Camp opted to enlist Amos Yadlin rather than Shaul Mofaz as its main security candidate, leaving Mofaz and Kadima stranded).

- Most significantly, the Arab-based parties (three Arab parties plus Hadash, based on the communist party, which includes Jewish members and a Jewish MK, but few Jewish voters) are expected to unite in one list, to overcome the new, higher threshold (more about that in a future post). In the charts above, I assume the Arab parties run together, though they may decide to run in two lists, which would still likely pass the threshold.

- Election “surprises” are common.

- The Center in Israel is notorious for “fad” parties that come and go, drawing undecided voters who may choose their list very close to elections day. In past elections, we’ve seen last minute surprises emerge, with undecided voters flocking to Lapid’s Yesh Atid (2013) or even to a retiree party (2006,) which garnered many young voters in search of a protest vote.

- The higher threshold also means that some smaller parties may be in for a bad surprise on election night, missing the threshold altogether. Seemingly safe parties, such as Meretz or Lieberman’s Yisrael Beitenu run some risk of a very rude awakening on March 18th. If this happens, their remaining votes will be forfeit, and the other parties will receive more seats, again, changing the landscape considerably.

- Most suspect in this regard is the new party HaAm Itanu, headed by Eli Yishai (a splinter of Shas, as I’ll describe in a later post), which is currently polling below the threshold.

- Polling numbers will change.With nearly two months to go, the polls will certainly change.

-

- With so many parties, polling is naturally difficult in Israel. For one thing, the campaigns themselves may have an effect. With good messaging and enough funds, parties may well outperform their current standing, while others fall behind. (Though political scientists tend to dismiss the effect of campaigns, the amounts of money spent on them suggest that the candidates, at least, believe in their efficacy.)

- There may also be strategic voting—voters may rally around the leader of their “camp” to try and decide the identity of the next prime minister (as in 2009, when Meretz lost votes to Kadima, which successfully framed the elections as a “Tzipi or Bibi” choice,) or they may try and balance the expected winner with their smaller party of choice (In 2006, Olmert’s Kadima lost votes to smaller parties after its victory appeared secure.)

- A joint Arab list may also galvanize Arab-Israeli voters to go the polls in greater numbers, increasing their representation in the Knesset (with about 20 percent of the population, low Arab turnout, and a low median age, resulting in just over 10 percent of the seats held by native Arabic speakers in various parties.)

- With all that said, reputable pollsters in Israel have done a reasonably good job over the years and the current polling numbers have been quite consistent for quite some time. This allows for, at least, a preliminary outlook on the elections as they stand today.

[1] Under Israeli electoral law (a “single district, proportional representation” system), voters do not elect candidates or regional representatives but rather choose one national list of candidates offered ahead of the polls by a party or an amalgam of parties. Each list that passes a minimum threshold (recently raised to 3.25 percent of the vote) is then awarded seats in the 120-seat Knesset, in proportion to the number of votes it received, nationally. The result is a highly representative—but highly fractured—party system. After the elections, the president (who is not up for general election), consults the elected factions and tasks one Member of Knesset with forming a government that can garner support of a majority of the Knesset (this need not be the leader of the largest faction, merely the MK with the best chance of forming a governing majority). In a party system as fractured as the Israeli one, this invariably entails forming coalitions among various factions in the new Knesset.

[2] Other useful resources include BICOM’s factsheet (where there are short descriptions of the various parties and leaders as well as a polling average) and the Hebrew “Project 61“, which includes useful graphics, though its averages sometimes include incommensurable polls.

[3] Note also that HaAm Itanu, Eli Yishai’s party which splintered from Shas, does not appear to pass the new threshold (3.25 percent), which would mean that its sole average seat (which may underestimate its power), would be awarded to another party.

[4] Herzog and Livni have already agreed on rotation should they win the election, but this agreement would be void should they have to share the term with another party altogether.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this post identified Kadima as ahead in 2009 by 28-27, not 29-28.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Israeli Elections: Who Will Win? (The Numbers, Take 1)

January 22, 2015