Concerns about students forgetting what they learned in the school year across a long summer break date back approximately 100 years. This phenomenon of losing academic skills during the summer, which is often referred to as “summer learning loss” or “summer slide,” is widely reported each summer. Additionally, there are long-standing concerns that summer slide is concentrated in high-poverty areas, as more affluent students may have access to certain types of enriching summer opportunities that students experiencing poverty may not have access to. The ubiquity of concern around summer learning loss and its perceived contribution to educational inequities has led many educators and parents to go to great lengths to provide academic opportunities to students during summer break.

However, a 2019 Education Next article by Paul von Hippel highlighted the lack of consensus in the field, calling into question how much we actually know about summer learning loss. The article focused on attempts to replicate a finding from a famous early study, the Beginning School Study, that showed unequal summer learning loss between low- and middle-income students in elementary school explained more than two thirds of the 8th grade socioeconomic achievement gap. von Hippel was unable to replicate these findings using two modern assessments and concluded that a major limitation of much of the early summer learning loss research was how the older assessments were scaled across grade levels (e.g., students were asked questions about 2nd grade content at the end of 2nd grade and then asked about 3rd grade content in the fall without accounting for the more difficult content).

In summary, von Hippel wrote, “So what do we know about summer learning loss? Less than we think. The problem could be serious, or it could be trivial. Children might lose a third of a year’s learning over summer vacation, or they might tread water. Achievement gaps might grow faster during summer vacations, or they might not.”

Here, we revisit the concerns raised in the Education Next article. In the context of pandemic-era school shutdowns and test score declines, “learning loss” has taken on new meaning—and perhaps new importance. We draw on recent research published since 2019 to address three big questions about summer learning:

- Is it possible to “lose” learning?

- Do summer learning loss patterns replicate across modern assessments?

- To the degree there are test score drops, are they concentrated among high-poverty students and schools?

It is possible (and natural) to “lose” learning

One might wonder whether it is possible to have “lost” knowledge/skills over a short period like a summer break. A common argument is that if learning can be lost over the span of a few months, there may not have been any real learning in the first place.

However, a long line of research on learning and cognition has shown that procedural skills and those that involve a number of steps tend to rapidly deteriorate in the absence of practice or other reinforcement (see summary in chapter two of this monograph). Furthermore, it is considered normal and healthy to forget a good deal of what one has learned and experienced. In fact, forgetting may also assist the development of procedural knowledge (skills) through a process of automatization, as individuals become less dependent on explicit knowledge and rely more on procedural skills.

All to say, (some) forgetting can be an important part of learning and not an indication that learning did not occur. But how much forgetting is normal during a summer break? And when does forgetting cross the line between “normal” and problematic? These are the million-dollar questions we’re still trying to answer.

Multiple assessments indicate that test scores flatten or drop during the summer

While our initial understanding of summer learning loss dates back to studies conducted in the 70s and 80s, a flurry of recently published studies now allows for a comparison of summer learning findings based on three modern assessments with large national (though not always nationally representative) samples. Unlike many earlier assessments, these three assessments (ECLS-K cognitive tests, MAP Growth, and i-Ready) are all built using item response theory (IRT) methods that allow for (a) better matching of item difficulty to student performance and (b) cross-grade linking which enables researchers to compare test scores across grade levels.

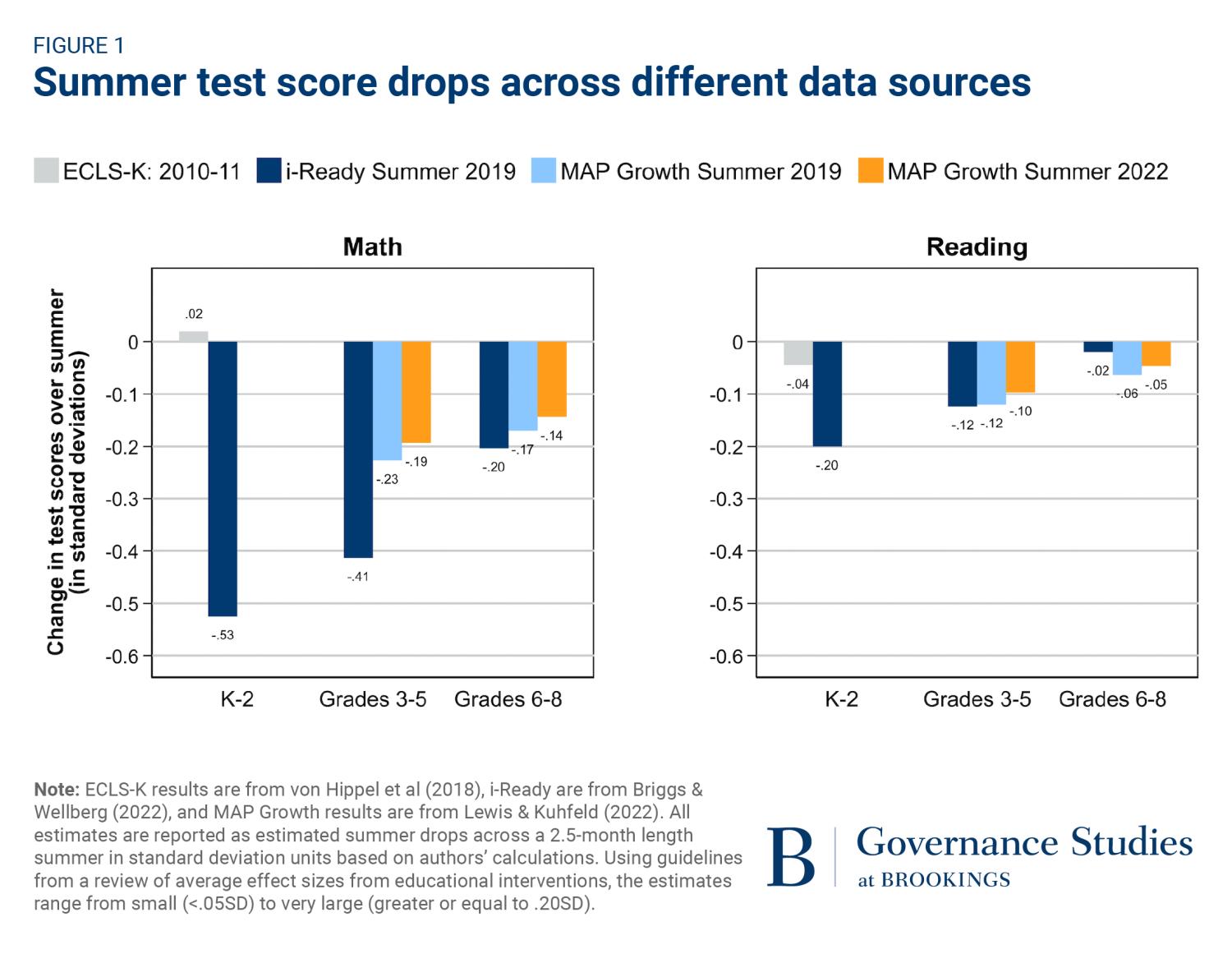

Across these studies, test scores flatten or drop on average during the summer, with larger drops typically in math than reading. This finding is highlighted in Figure 1, which compares summer learning estimates in standard deviation (SD) units from three large analyses of student test scores. Studies using test scores from ECLS-K:2011 show that student learning slows down but does not drop over the summers after kindergarten and 1st grade, while research using interim and diagnostic assessments (MAP Growth and i-Ready) has found far larger summer drops across a range of grade levels.

These studies consistently show that summer learning patterns are starkly different from school year learning patterns. However, there is wide variation across assessments, with estimates ranging from inconsequential to alarming in magnitude. How is it possible that one test indicates an average gain of .02 SD over a summer while a different test indicates a huge drop of .50 SD? The answer is unclear. While the modern assessments are not subject to the limitations of the older approaches highlighted by von Hippel, they still differ in their purpose, design, content, and administration. For example, ECLS-K tests are administered one-on-one with a test proctor sitting with each child and measure a broad range of early math and literacy skills, while MAP Growth is administered on a tablet/laptop (with audio supports in younger grades) and measures the skills specified by the state’s content standards. Additionally, analysts use different strategies to estimate summer test score drops, from simply subtracting a fall score from the spring score to more complicated modeling approaches that adjust for the weeks in school elapsed before/after testing. The i-Ready analysis demonstrated that different analytical approaches can yield very different results (for example, a gain of .02SD versus a drop of .22SD).

It is important to note, however, that focusing on average drops hides an important finding: there is a huge amount of variability across students in test score patterns over the summer. One study found that a little more than half of students had test score drops during the summer, while the other half actually made learning gains over summer break. Students’ race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status only explain about 4% of the variance in summer learning rates, and we still have only a limited understanding of the mechanisms that explain the remaining variability.

Contrary to prior research, recent data does not show that summer test score drops are concentrated among students in poverty

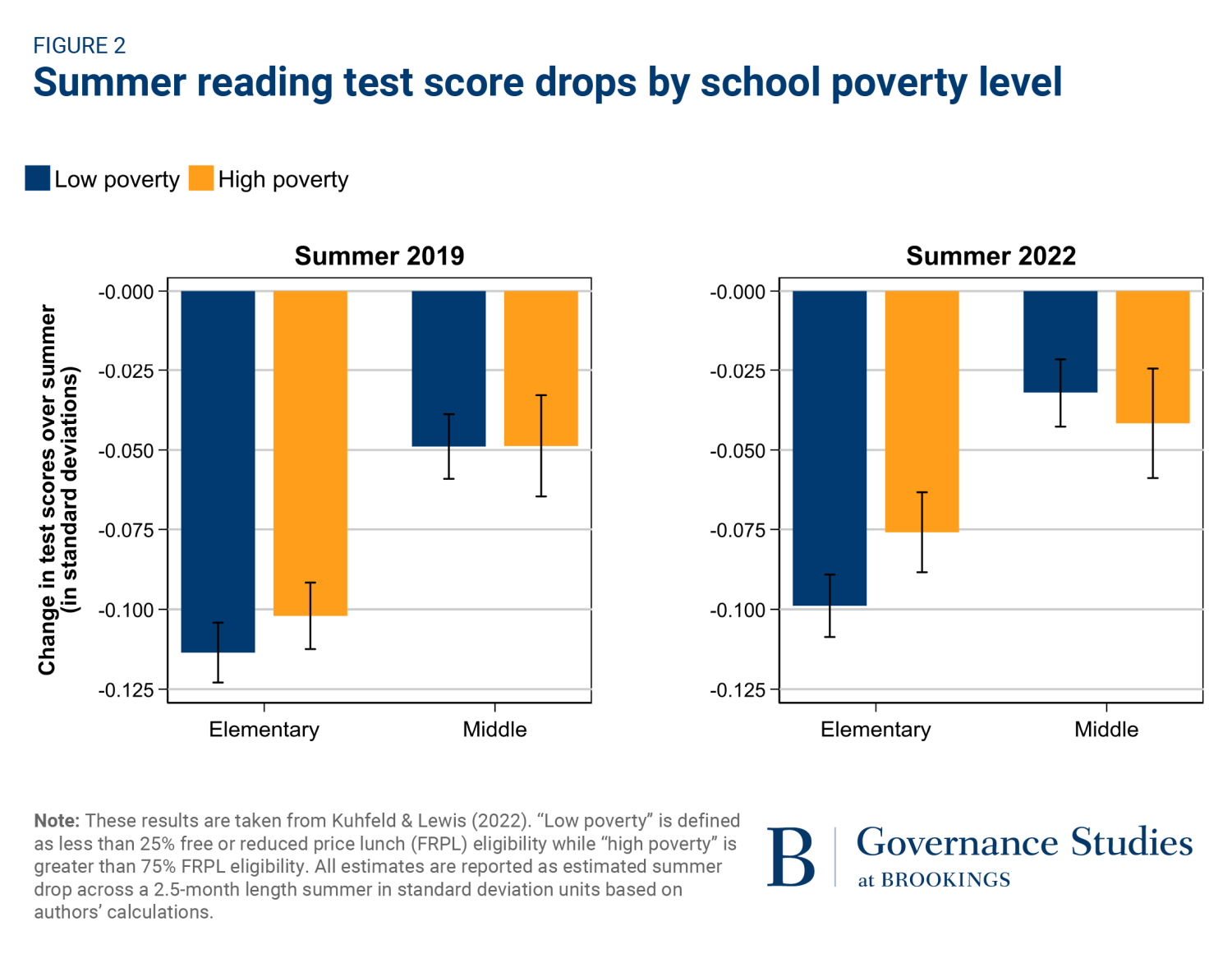

A meta-analysis of summer learning studies from the 1970s to 1990s found that income-based reading gaps grew over the summer. Researchers theorized that many high-income students have access to financial and human capital resources over the summer, while low-income students do not. However, a multi-dataset study conducted just prior to the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that gaps between students attending low- and high-poverty schools do not appear to significantly widen during the summer. Additionally, we recently examined differences in summer learning patterns by school poverty level using MAP Growth test score data collected just prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 2 shows that the test declines for students in high-poverty schools were either statistically indistinguishable or less extreme than those for students in low-poverty schools in both summer 2019 and summer 2022. In other words, there is little evidence from recent data to support the earlier finding that the summer period contributes meaningfully to widening test score gaps across poverty levels.

Summary

What have we learned since von Hippel asked in 2019 whether summer learning loss is real? While the story is still pretty mixed in the early grades, we consistently observe average test score drops during the summer in 3rd through 8th grade. However, differences in the magnitude of test score drops across studies imply that we still cannot say with certainty whether summer learning loss is a trivial or serious issue. This is particularly true in reading where the magnitudes of test score declines during the summer are smaller than in math (which may be attributable to more exposure to opportunities for reading during the summer months compared to math). Additionally, researchers need to pay more attention to the considerable amount of variability across students in summer learning patterns, with many students showing test score gains during the summer. That is to say, summer test score declines are not destiny, but we still know little about who is most vulnerable to forgetting academic skills during the summer. However, these new data show us that, contrary to popular belief, we can say that test score drops do not appear to be concentrated among students experiencing poverty.

Educators may be wondering what the right path forward is in the meantime until the debate is settled. Whether summer learning loss is real or if learning simply stagnates in the summer, we believe it is less harmful to assume the former and act accordingly (e.g., offering high-quality summer learning opportunities to students) than it is to assume the latter and do nothing. In short, despite the ongoing debate, we will continue to advocate for additional summer opportunities and prioritizing these opportunities for students who would most benefit.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).