After a decade of high growth and high expectations about Latin America’s future, a new global context is already contributing to a major economic slowdown in the region and to a deterioration of the macroeconomic fundamentals and the political climate.

On October 21, the Brookings-CERES Economic and Social Policy in Latin America Initiative (ESPLA) and El País de Madrid co-hosted a discussion in Spanish with a group of prestigious economists, policymakers, and journalists on the macroeconomic, social, and political challenges that lie ahead for the Latin American region.

These are the key insights that emerged from the discussion:

On macroeconomic adjustment

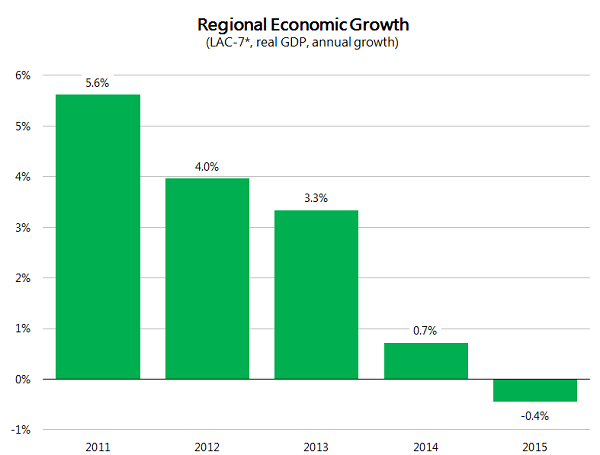

An economic downturn in China, declining commodity prices, the prospect of rising U.S. interest rates, and an increase in the perception of risk towards emerging markets have led to a significant slowdown in growth rates. For the region as a whole, output is predicted to contract in 2015.

Sources: IMF World Economic Outlook October 2015 and private estimates for Argentina.

*LAC-7 includes Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Venezuela, which represent 90% of Latin America’s GDP.

Three decades ago, this set of conditions might have been accompanied by currency crises, debt crises, and/or banking crises, perhaps even coup d’états.

Much has changed since then for several countries in Latin America. Many of them today have well-capitalized banking systems, high international liquidity relative to short-term debt, access to the lender-of-last-resort facilities of the International Monetary Fund and relatively stable political systems. Interestingly, policies in the region are likely to face more conventional monetary and fiscal challenges.

On the monetary side, countries will adjust differently to the new and more adverse global environment depending on initial conditions. Countries with low baseline inflation, such as Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico, can afford to keep interest rates constant—or even lower them— while allowing inflation to increase moderately without compromising credibility. However, countries like Brazil, with inflation at almost 10 percent per year, cannot afford this luxury. As a result, Brazil needs to raise interest rates to keep inflation under control at the cost of deepening recessionary pressures.

On the fiscal side, governments need to balance a smooth adjustment to the new external context while maintaining credibility in public finances. Again, initial conditions play a key role. Countries like Chile and Peru, with relatively low fiscal deficits and public debt, have more leeway to pursue fiscal consolidation gradually over time and avoid pro-cyclical fiscal adjustments. By contrast, countries like Brazil, with high fiscal deficits and public debt, need to carry out major adjustments to shore up credibility and credit worthiness, but at the expense of deepening recessionary pressures.

Although the region has been adapting to the more stringent external conditions for the last three years, the macroeconomic adjustment process is not yet over. Moreover, not only might it require an accommodation to a cyclical contraction but to a permanently lower long-run growth rate. This accommodation will differ in size and magnitude across countries in the region.

Beyond macroeconomic adjustment and given the sluggish growth prospects and the fact that Latin America relies heavily on external cycles, much more could be done to increase productivity, to diversify economies, and to strengthen institutions to foster higher economic growth in the medium and long term.

On democracy and institutions

Over the past century, Latin America recorded a total of 36 coup d’états. In years past, it would have been unthinkable to foresee the rise of democracy and civil liberties that the region has experienced. In fact, according to The Economist Democracy Index of 2014, 61.1 percent of all Latin American countries are categorized as democracies.

Although democracy is well-established, most countries in the region were not yet able to transform their societies into modern states with institutional capacity that provides high-quality public services, reins in corruption and promotes economic development.

However, this combined with declining economic conditions, has led to decreasing approval ratings of governments and the loss of popularity of the incumbent presidents. However, it is a very positive sign that this has not translated into a lack of governance. With the exception of Brazil, where the Petrobras scandal has paralyzed the government, most other governments are still able to govern effectively.

On the middle class

After 15 years of sustained growth, 66 percent of Latin Americans consider themselves part of the middle class. In fact, according to the World Bank’s recent study, the middle class in Latin America recently hit an historic high. This is a major success that has been mainly driven by high growth and formal job creation.

However, the emerging and still vulnerable middle classes feel threatened. Thus, politically viable macroeconomic adjustments will need to take into account the employment and distributional dimensions of these adjustments to a much larger extent than in the past. Not doing so, could result in a political backlash.

Commentary

Is Latin America prepared to resist global economic turbulence?

November 18, 2015