This piece complements a written exchange on China and North Korea’s nuclear dynamics, published as part of the Global China project.

The written exchange among my colleagues does much to enhance our understanding of the dynamics of relations between the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and how this problematic relationship may impact the goal of denuclearizing North Korea. With the possibility of a U.S.-PRC leadership summit at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum on the horizon, and with both the United States and North Korea hinting at possible diplomatic reengagement, their conversation is timely.

They ask the right questions, particularly whether China is an enabler or a stabilizer when it comes to dealing with North Korea’s ongoing development of robust nuclear weapons and ballistic missile capabilities.

I found much to agree with in their analysis. But, as a longtime Korea and China hand, and as someone who has been immersed in the North Korea nuclear issue for decades, let me offer another perspective on several points they make in their analysis.

North Korea’s intransigence

The first point is to underscore that the lack of progress in denuclearizing North Korea stems from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea’s (DPRK) refusal to engage with the United States on denuclearization. That position has now been codified as a matter of national policy by Kim Jong Un.

The problem also lies in the DPRK’s determination to retain its nuclear capabilities at all costs, and its refusal to acknowledge the full scope of its program. This, of course, resulted in the breakdown of U.S.-North Korea dialogue in Hanoi in 2019. Accordingly, the lack of progress on denuclearization is a result of Pyongyang’s intransigence and its ongoing attempt to convince the international community to accept the DPRK as a permanent nuclear-armed state.

China’s silence, Russia’s support

Regrettably, Russia has all but agreed to accept North Korea’s nuclear status, describing the denuclearization issue as “closed.” Previewing its intentions, Moscow played a key role in ending the mandate of the U.N. panel of experts in 2024, a step that has greatly complicated the international community’s ability to monitor the DPRK’s nuclear weapons program.

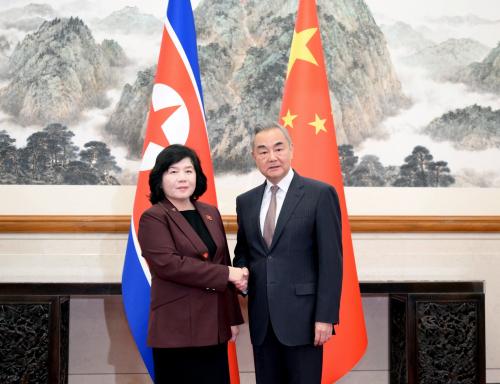

Meanwhile, China appears to be moving in the same direction, most recently by removing references to denuclearization from its statements on North Korea, including its official readout of Xi Jinping’s meeting with Kim in Beijing. Beijing’s new public silence about denuclearization is both cynical and concerning. It comes at a time when Pyongyang has declared that there is no longer room for discussion of denuclearization as it tries to slam the door shut on any hope that denuclearization may still be possible. To emphasize the point, North Korea has hinted that the price the United States would have to pay for renewed talks would be Washington’s agreement to forswear raising the issue of denuclearization.

In this context, the assertion that China remains committed to North Korea’s denuclearization is questionable, to say the least.

Beijing’s self-serving approach to North Korea cannot be overestimated. China is standing by in silence as North Korea develops a dangerous new security partnership with Russia that threatens Ukraine and Europe as well as NATO’s goals with respect to the defense of Ukrainian territory and sovereignty. China’s approach speaks volumes about its intention to prioritize its relationship with the DPRK ahead of denuclearization. As a result, the time when we can assume, or even hope, that China would be helpful on this issue appears to be ending.

China also understands, as North Korea does, that U.S.-DPRK talks that focus on “risk reduction” rather than denuclearization would effectively accept the idea that Pyongyang will continue to be a nuclear-armed state. Under such circumstances, the new topics of bilateral dialogue would likely center on how large an arsenal Pyongyang would have, whether it would continue to test its nuclear weapons, and whether it would limit its missile forces in some way. Pyongyang has made clear that its right to possess such weapons is not to be questioned.

Is China changing its mind?

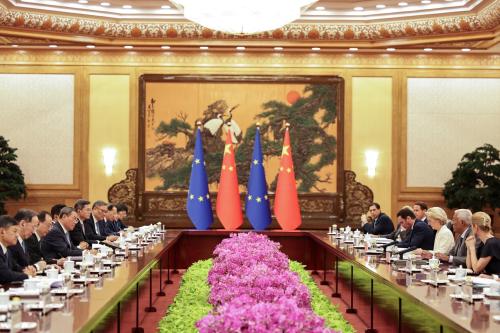

A critical question at this moment, considering the shift we have seen in recent Chinese rhetoric and actions, is whether the PRC is changing its policy on a nuclear-armed North Korea along the lines of Russia’s move. Answering this question may yield evidence that Beijing is indeed now following Moscow’s lead in declaring the denuclearization issue “closed.” If it does, it will demonstrate that there is no longer a “shared commitment” between Beijing and Washington regarding denuclearization. It will also raise serious questions about whether there are indeed “opportunities for coordination” between the United States and China on the nuclear issue.

Every policy utterance from senior levels of the DPRK in recent months has reinforced the point that North Korea intends to remain a nuclear-armed state, that discussion of denuclearization is not acceptable, and that the DPRK intends to enhance and expand its nuclear and missile arsenals. Russia has now all but accepted this as the new reality. Beijing may be in the process of doing so, as well.

Considering this, a fifth question should be added to the four posed to my colleagues in their dialogue: If Russia’s and China’s shift means that denuclearization is now dead as a serious and attainable policy goal, then what is left for the United States and China to talk about when it comes to North Korea?

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Is China committed to North Korean denuclearization?

October 20, 2025