Introduction

The passage of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 (IIJA), the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 (CHIPS), and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) enabled generational federal investments in infrastructure, clean energy, innovation, and economic security. Our earlier analysis identified more than $464 billion in immediate appropriations with particular significance to the community and economic development aspirations of rural places.1

Many of these programs award their funds to intermediaries, who then assume the responsibility for deciding upon and regranting those funds to their ultimate recipients. Out of the 111 programs that we initially cataloged as having particular significance to rural places, we analyze here a subset of 40 programs that award their funding through intermediaries.2

Together, these programs comprise over $218 billion in funding—nearly half of the total rural-significant appropriations from our earlier analysis. Amid the magnitude of the opportunity, understanding the timing and the pathways for distributing these funds has important implications for rural communities, since they often face significant challenges in accessing federal investment.

A significant role for intermediaries

Depending upon the program, these intermediaries can include state governments, tribal governments, or nonprofit organizations. We tracked all awards that a federal agency had announced by October 16, 2024.

State and tribal governments dominate as the type of intermediary, together responsible for more than three-fourths of these programs, and eligible to serve as intermediaries for another three. While nonprofits are solely responsible for just six programs, those combined resources total almost $30 billion in appropriations.

Timing and distribution

For these programs, the announcement of a federal award or selection simply starts the process of allocating the funds and thus offers limited insight into which communities ultimately receive the money.

Several additional steps must be taken for the money to reach its final recipients. First, an announced award must turn into a federal obligation—a signed agreement that legally commits the federal agency to disburse the funds to the intermediary.3

The intermediary then undertakes regranting the funds. This requires multiple steps, from defining and creating grant processes to assessing projects and making funding decisions. Intermediaries are provided ample time—usually a period of years—to distribute the money and manage the awards responsibly.

By analyzing stipulations in the originating legislation, notices of funding opportunities, agency implementation guidance, and applications for funding, we estimated the end dates by which the intermediaries are committed to fully expend the funds for specific programs.4

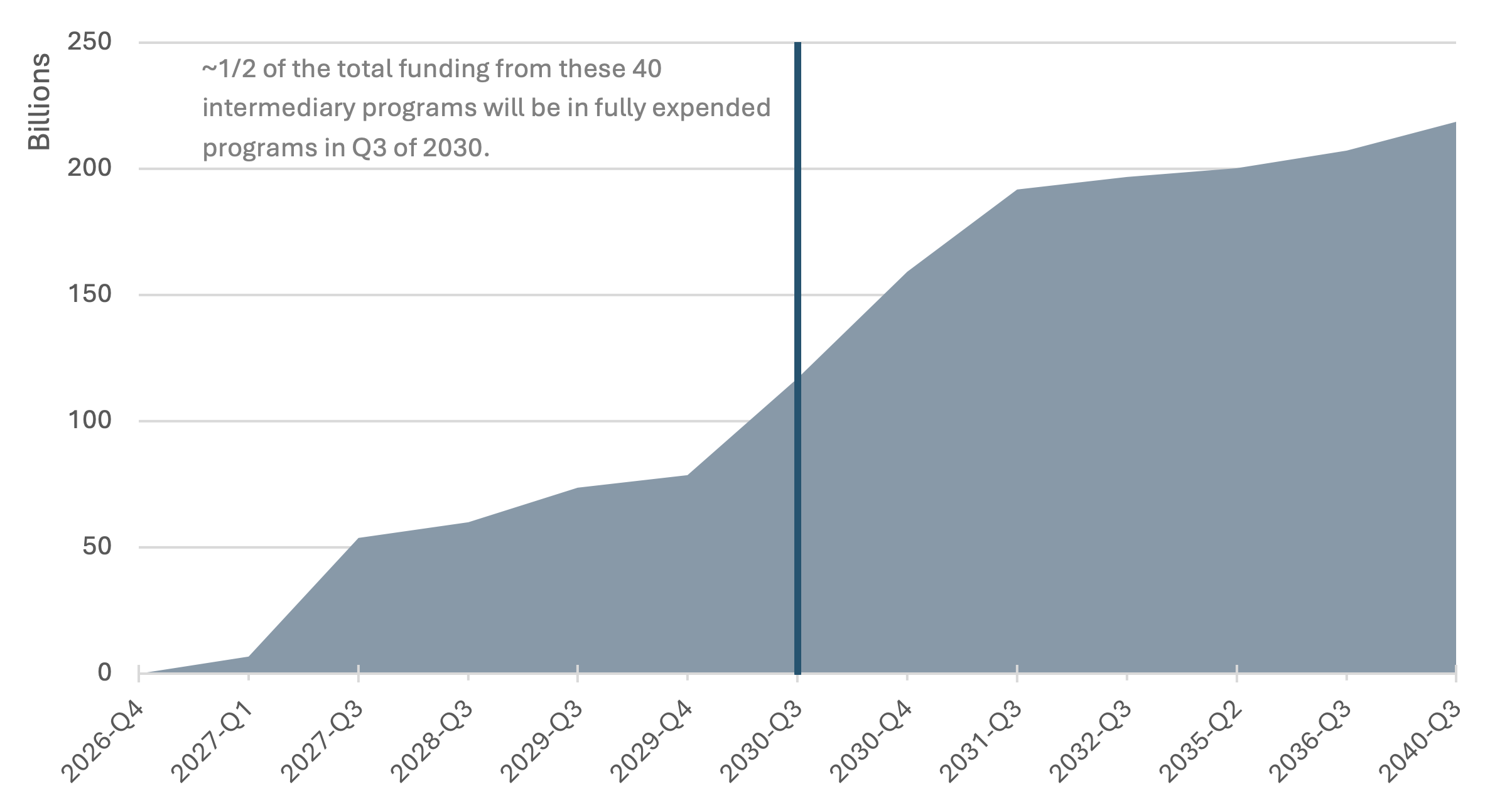

Figure 1. Cumulative value of fully expended intermediary programs in IIJA & IRA that are rural-significant

Source: Authors’ analysis based on stipulations in the originating legislation, notices of funding opportunities, agency implementation guidance, and applications for funding.

We estimate that 17 of these programs, worth just over $60 billion, could fully exhaust their funds by the end of 2028. For these programs, the next four years will be critical.

However, out of the remaining programs, 15 could still be regranting past the beginning of 2030.

Allocations

These appropriations are allocated in two different ways: one-time awards and recurrent awards. More than 56% of this total—$123 billion—is being distributed to the intermediary via regular annual apportionments for a set period. These apportionments run at least through FY2026, with selected programs extending beyond that. State governments are the intermediaries for almost all these programs.

The other $94 billion in funding will go to an intermediary via a one-time award from a federal agency or department. The time period that the intermediary has for fully sub-granting the money will vary based on stipulations in the original legislation or parameters set by the originating federal entity.

Most of the programs with annual apportionments have multiple apportionments left, so only about half of those appropriations had been selected for distribution at the time of our analysis.

In the single-award category, agencies have announced award selections for almost 85% of the resources (though such announcements do not constitute legal obligations).

Overall, the value of the announced awardees adds up to a little more than two-thirds of the total $218.7 billion that intermediaries will eventually distribute.

Investment areas

These intermediary programs encompass nine different federal departments, with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Department of Transportation (DOT) together overseeing more than half of the 40 programs.

The programs span multiple sectors, with water, broadband, and climate programs each valued at more than $40 billion. Water constitutes the largest sector, totaling more than $48 billion, with about 40% awarded by now to its intermediaries, which are state governments. The Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment Program (BEAD) is the largest single program, distributing $42.5 billion to close the broadband gap. Fifty-five of the eligible 56 states and territories for the program have had their plans approved by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), an agency within the Department of Commerce, to enable funding to begin to flow to projects.

Ten of the programs have mitigation or adaptation to changes in the climate as their sole objective and are thus categorized as belonging to the climate sector in the above graph. Yet, this does not encompass the full breadth of programs that represent action to address changes in the climate.

Nine programs belonging to other sectors also seek as a primary objective to make a direct impact on mitigation or adaption. Thus, 19 of the 40 programs distributed through intermediaries are climate-focused.

We considered 11 other programs to be climate-relevant because they seek to make at least an indirect impact on climate change or highlight it as a secondary consideration.5

Combining the climate-focused and climate-relevant programs means that three-fourths of the intermediary programs, constituting almost 60% of the resources, have an interest in mitigating or adapting to impacts from changes to the climate. Regranting from these programs could continue well beyond the 2028 presidential election, even for major programs such as the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, which consists of three programs valued at $27 billion total. Eleven of those programs are overseen by the EPA, and all seven of the programs overseen by the Department of Energy are climate-focused.

Appendix I lists all 40 intermediary programs that were analyzed, organized by climate-focused, climate-relevant, and other.

Key implications

While federal awards to intermediaries are proceeding quickly, full implementation and sub-granting is likely to stretch for years. For a sizable portion of the rural-significant opportunities in IIJA and IRA, the critical implementer is an intermediary. Some of the deadlines for fully expending their funds stretch well into the next decade and will span at least one change in presidential administration.

State governments bear a substantial amount of responsibility in deciding the allocation of rural-significant resources from the IIJA and IRA. States are eligible intermediaries for 85% of these programs, valued at more than $189 billion in total. It will be incumbent upon states to ensure that funding is distributed in a way that reflects the original intent of the resources and to be sensitive to the unique constraints of rural communities so that they receive their fair share of these federal resources. States should aspire to provide timely data on their spending transparently, consistently, and accessibly, so their stakeholders and constituents can track their decisions.

Federal agencies must provide clear and proper guidance sensitive to the constraints of intermediaries to ensure an effective sub-granting process. Timely and clear direction to intermediaries will be crucial for enabling them to act efficiently and effectively. Proper oversight from federal agencies will also be critical to ensure accountability in the regranting process. This includes providing opportunities for feedback from local jurisdictions and stakeholders who constitute the ultimate recipients, so they have recourse when an intermediary is ineffective or acting improperly.

Federal agencies, state governments, and philanthropic foundations must remain committed to strengthening local rural capacity and providing technical assistance. Many local rural communities still have a great deal of work to do to develop application-worthy projects and partnerships to access the resources in these programs. As regranting will last for years, they will continue to need support to successfully apply, secure, and manage investments from the intermediaries that will be managing these resources.

Rural officials, practitioners, and advocates would benefit from engaging these intermediaries directly. It will be important for these intermediaries to be sensitive to the unique capacity constraints of rural communities, to minimize the barriers and maximize the accessibility of their resources. Direct engagement by rural communities will help educate and improve the chances of a level playing field as intermediaries design and implement their programs.

Complete, timely, and centralized data transparency is essential for successfully maximizing the public benefit of these investments. The public availability of spending data on sub-grants is notoriously sparse and unreliable. In November of 2023, the Government Accounting Office (GAO) found rampant examples of missing or incorrect data on USASpending.gov, the site that hosts federal financial information as mandated by the Digital Accountability and Transparency Act (DATA Act) of 2014. Almost 50 agencies had yet to report their data from the previous year, and the missing information from just over half of those amounted to $5 billion in expenditures.

None of this bodes well for knowing who is receiving the sub-grants and who is being overlooked as these programs roll out. Bipartisan legislation has been proposed to review, update, and expand sub-award reporting, but the executive branch can act swiftly and unilaterally to improve its own reporting. Federal agencies must undertake and improve their efforts to publish timely, accurate, and accessible data on sub-grants, so stakeholders know the extent to which the grants managed by these nonprofits, state and tribal governments are reaching underserved rural communities.

Appendix I: Rural-significant intermediary programs in IIJA and IRA

-

Footnotes

- We refer to these programs as rural-significant.

- Note that CHIPS did not appropriate funding for its intermediary programs, so the results of this analysis are drawn solely from IIJA and IRA. We have also chosen to exclude the Surface Transportation Block Grants (STBG) administered by the Department of Transportation (DOT) because of its size (a supplemental of $72 billion) and its formulaic administration.

- Note that there can be a time lag between the announcement of an award from a federal agency to an intermediary and the execution of a legal agreement obligating the funds, as well as a time lag for publicly reporting the obligation on the official government platform USASpending.gov.

- Where no specific end date for regranting was available, we set the date as six months from the last apportionment of funds by the federal agency to the intermediary.

- See Appendix I for the full breakdown of categorizations.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Major IIJA and IRA funding opportunities for rural America will be implemented by intermediaries—and may take years

November 19, 2024